From Studio 54 To Carl Craig, A Wave of Dance Fever Hits The Exhibition Circuit

It all seems like it was very long ago now, but for a moment the art world was in the grip of dance fever. There was La Bôite de Nuit, an architectural appraisal of mostly European discotheques at Villa Noailles in 2017, followed the next year by the Vitra Design Museum’s Machines for Dancing: Club Design and the Evolution of Desire, Seduction, and Utopia. The racier Cruising Pavilion shows in Venice, New York, and Stockholm ducked into and recreated real and imaginary spaces for various kinds of body moving. And then, this winter, for a brief moment, there were more.

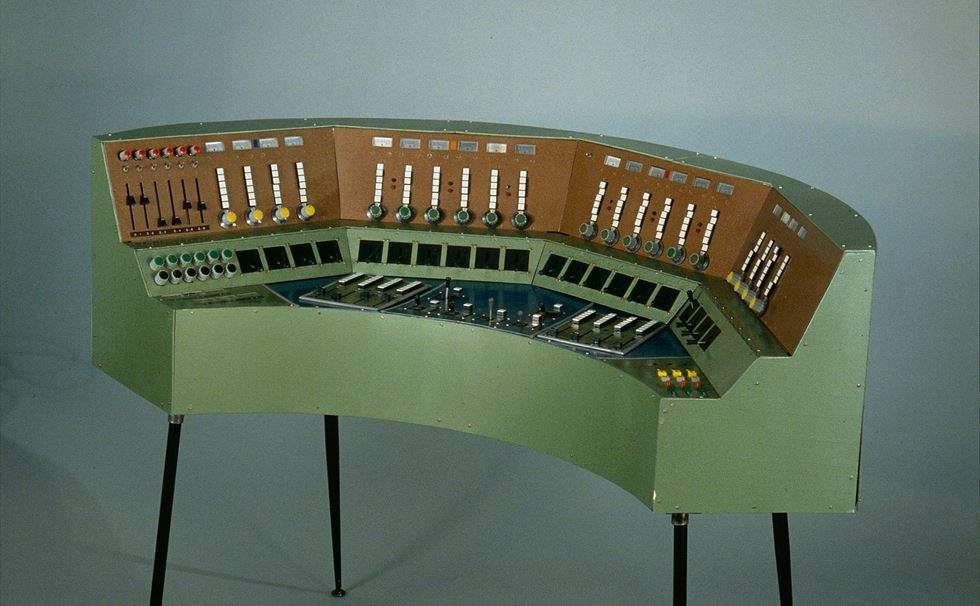

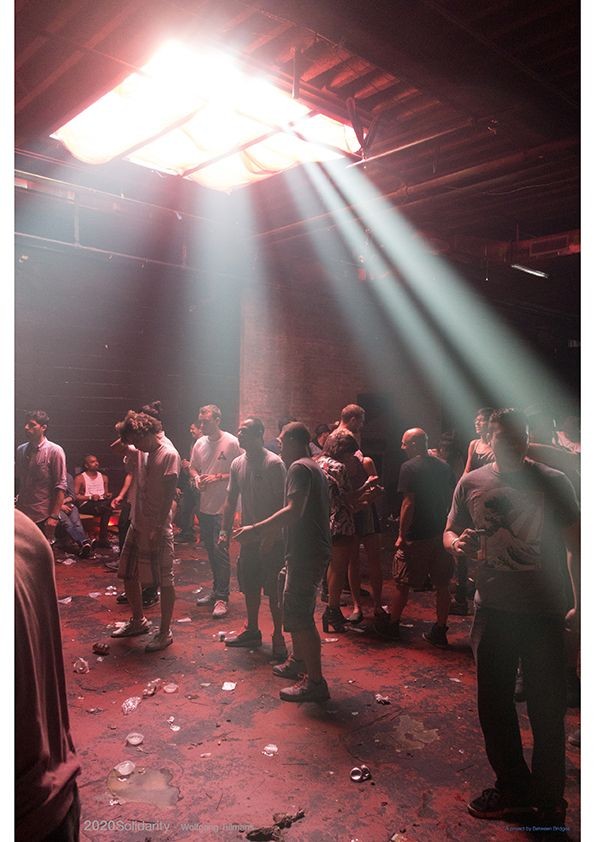

London’s Design Museum announced a blockbuster spring/summer exhibition, Electronic: from Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers, a look at the “hypnotic world” of dance music with a light and video show synched to bespoke Laurent Garnier beats. In New York, two institutions looked back to more specific milieus. Dia Beacon gave its basement over to Detroit techno legend Carl Craig; Party/After-Party, which opened on March 6 with an absolutely mind-bending live collaboration between Craig and Basic Channel co-founder Moritz von Oswald, comprised light interventions designed by John Torres and a sound installation which mixed with the long reverb and other wild acoustical phenomenon of the vast underground space. In just a few gestures (a spotlight or two, a loudening kick drum, louvered shutters across the windows triumphantly opening à la Berlin’s Panorama Bar to flood the place with sunlight), Craig managed to honor rave’s genius for transforming industrial spaces into oases for people of color, queers, and others on the margins without gentrifying the thrill.

-

Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, installation view, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. Photography by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

-

Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, installation view, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. Photography by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

-

Carl Craig and Moritz Von Oswald performance at Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York, Saturday, March 7, 2020. Photography by Eva Deitch, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

-

Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, installation view, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. Photography by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

-

Carl Craig: Party/After-Party, installation view, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York. Photography by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

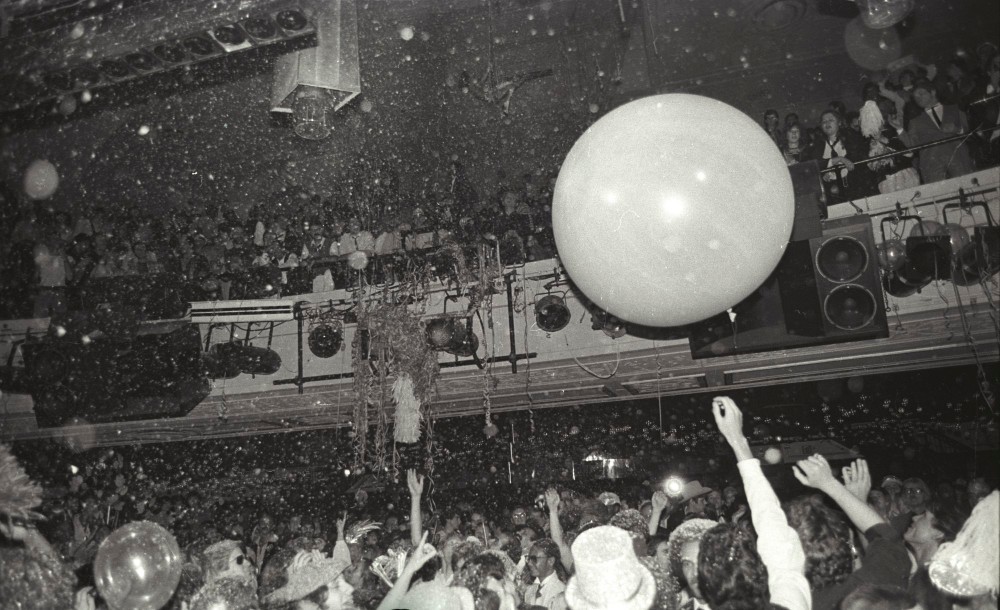

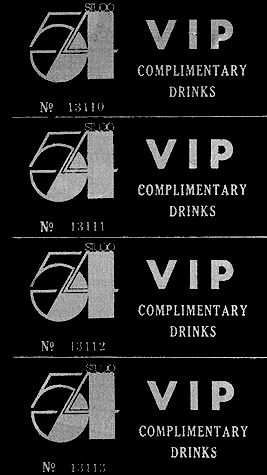

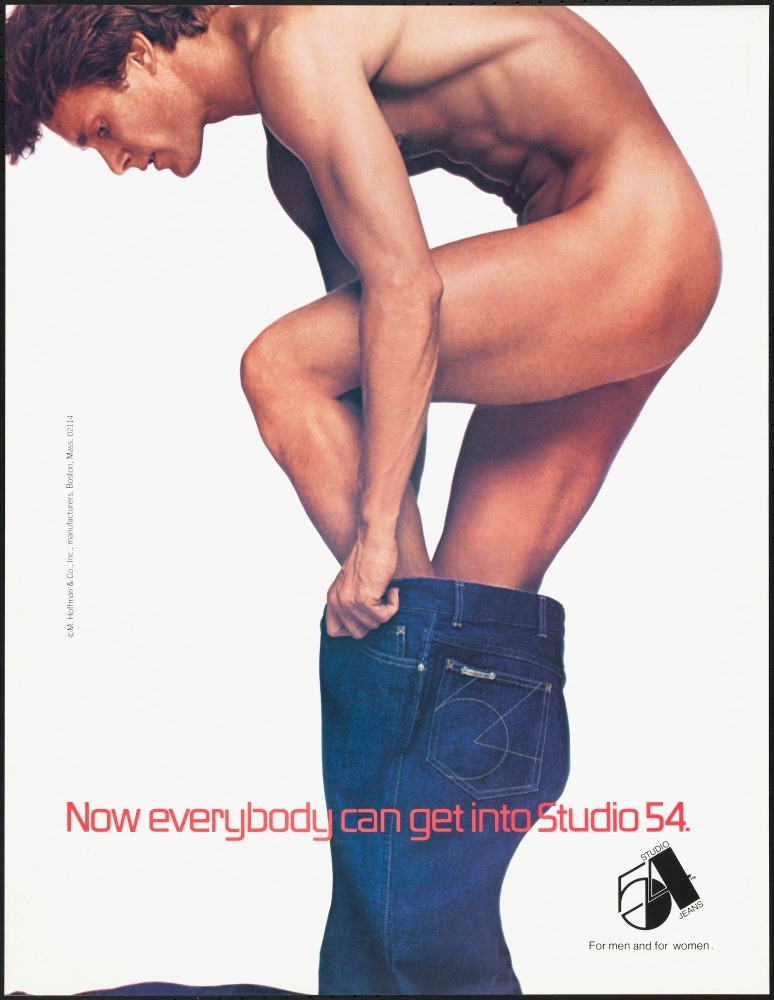

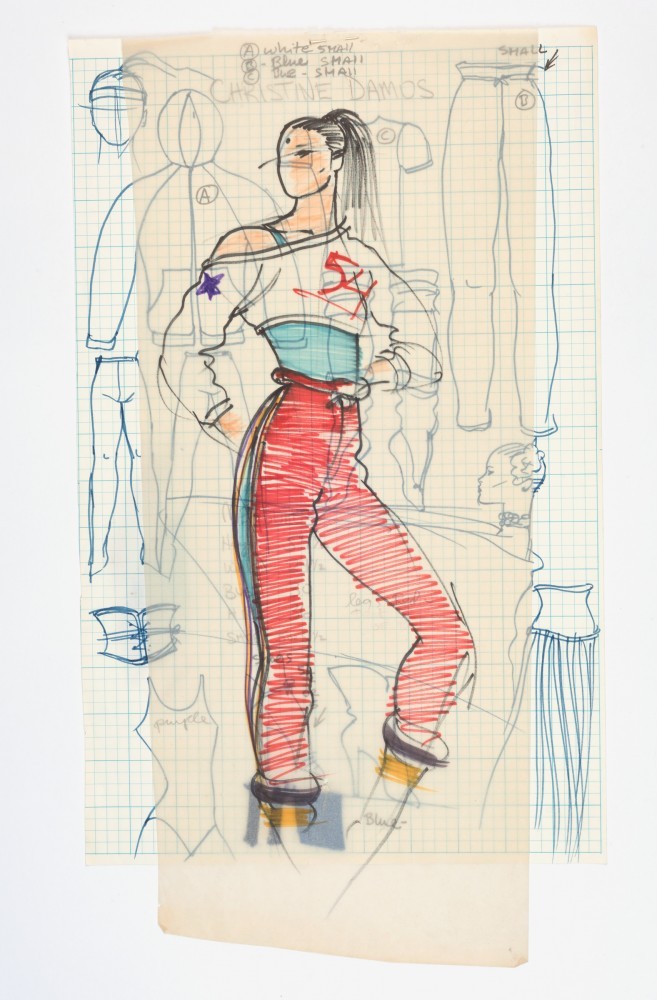

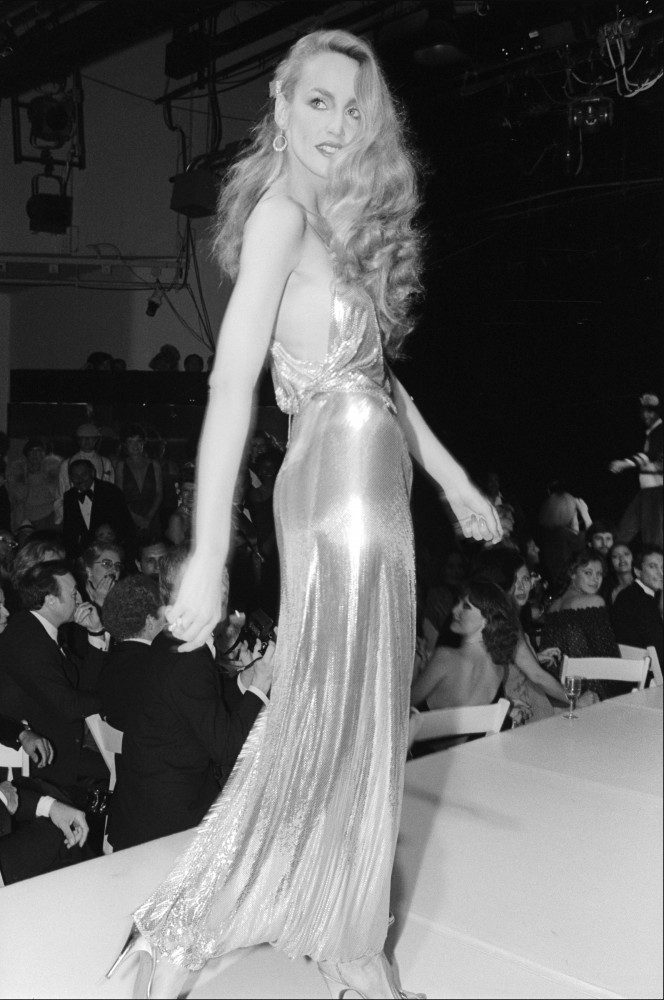

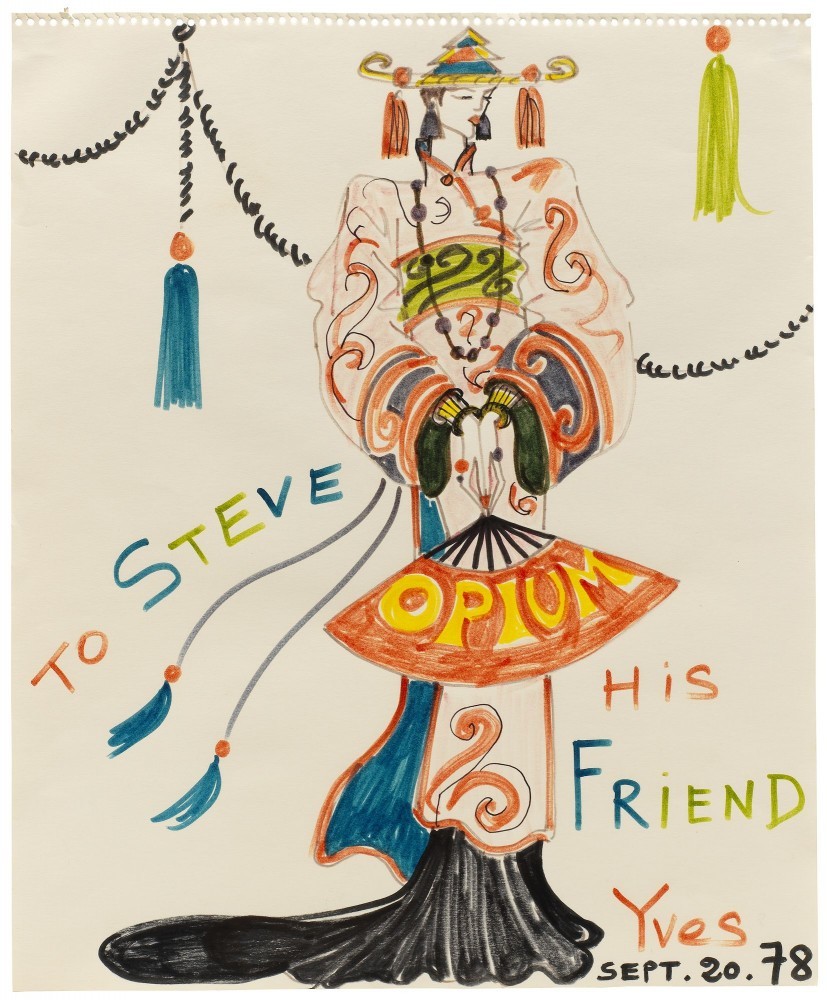

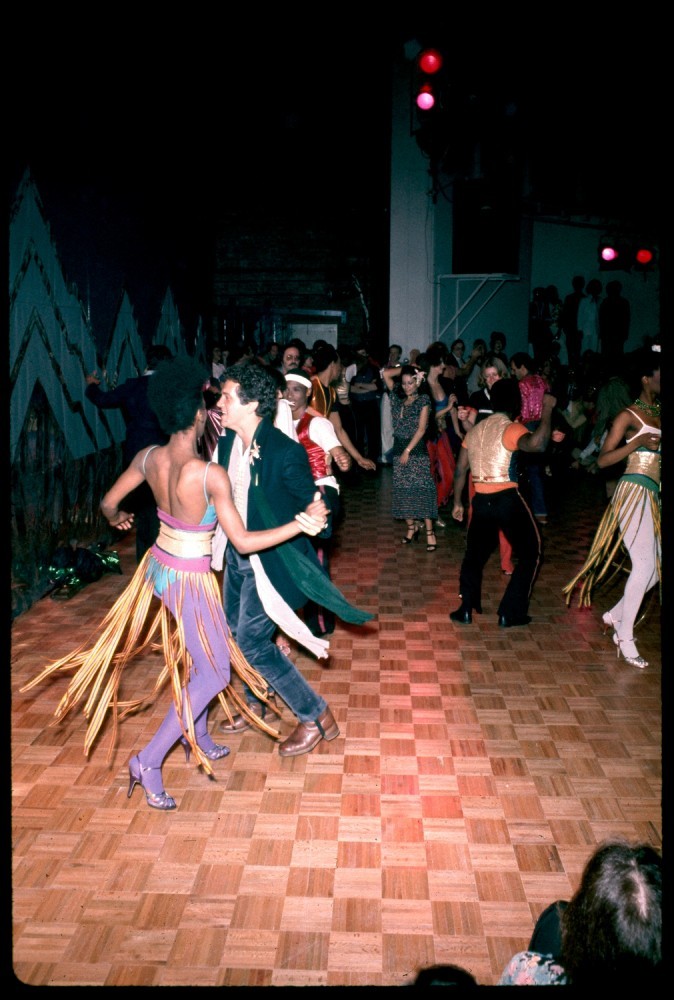

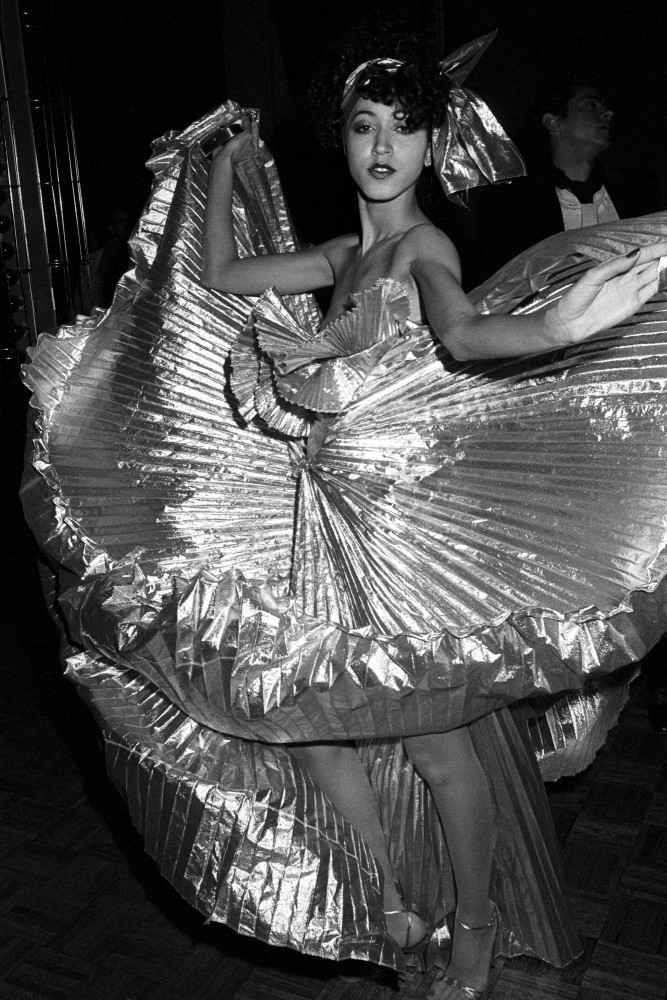

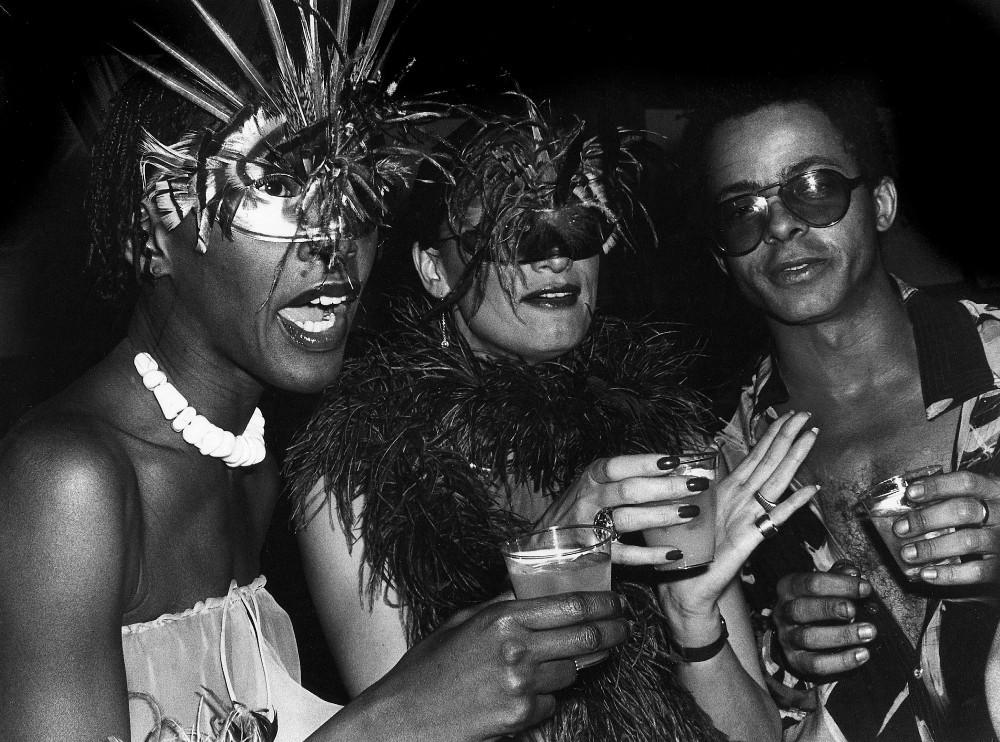

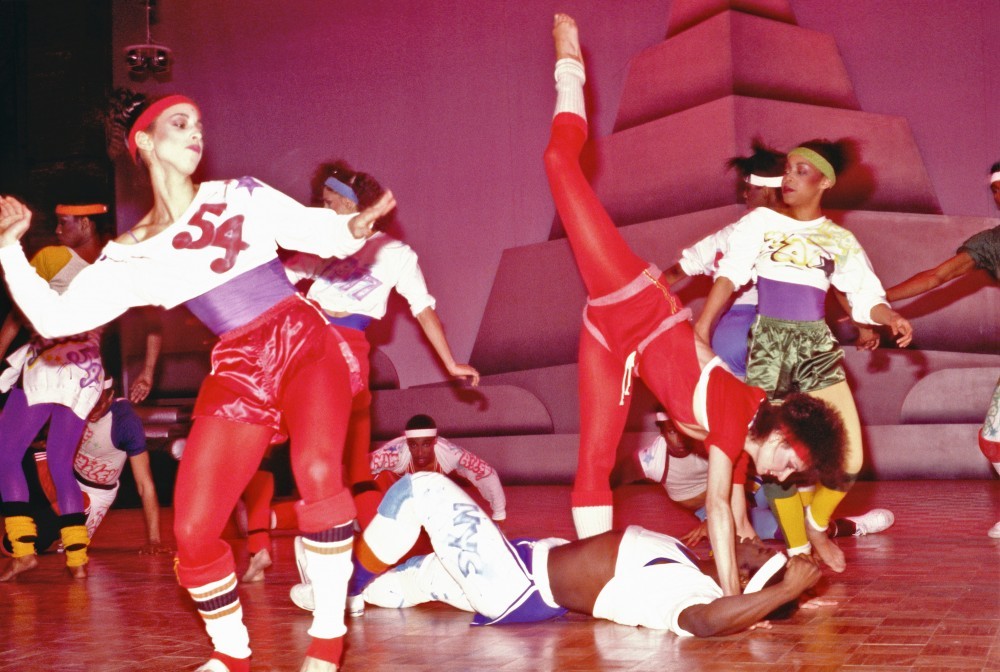

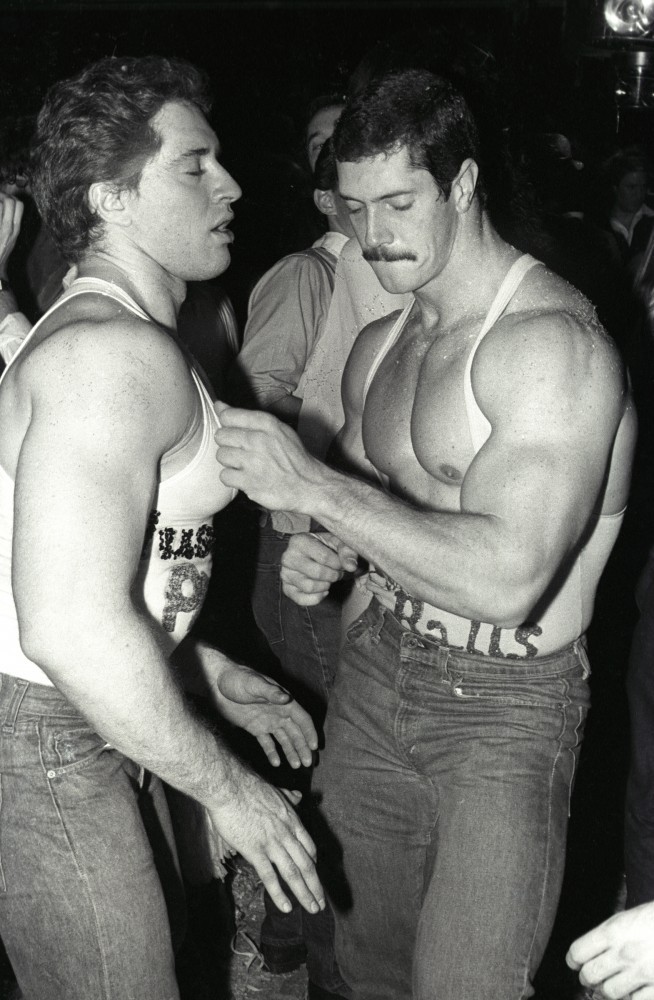

Which, of course, was the entire point of Studio 54 — a playground for those adventurous or fashionable enough to desire the magic compound of sex, drugs, and disco formulated at the Loft and the Paradise Garage but too rich or scared to actually go to these progenitors. The famed nightclub was the star of the Brooklyn Museum’s latest megashow, Studio 54: Night Magic, which opened the week after Craig’s show at Dia. It contains fabulous relics of the club’s striking graphic design; the superb theatrical stagecraft of Experience Space, a team of architects and interior, lighting, and floral designers; lots of fun photos of hunky guys snorting blow and Grace Jones playing by her own rules to beat everyone at their own games; and Amanda Lear’s clothes. The various vignettes are fun. But the show is strangely heady, in the sense of encouraging visitors to stand and look at the glamor without offering a chance to join in, as Craig manages to do at Dia. It also all but ignores Studio 54’s infamous door policy, designed to keep out most of the people actually responsible for creating the world it supposedly celebrated. “Studio 54 was a space of liberation,” reads a piece of wall text, “where people from diverse sexual, sociopolitical, and financial strata could find refuge and commonality.” All that and still room for Bianca Jagger to ride around on a white horse? (Nile Rodgers sure didn’t think so; check out the original lyrics to “Freak Out” for his thoughts.) Night Magic does a fine job of gathering together disco detritus — and I really do want the gift shop’s baseball cap emblazoned with a coke-snorting moon — but it won’t give you any sense of how or why a DJ might save your life.

-

Rose Hartman, Bianca Jagger Celebrating her Birthday, Studio 54, 1977: Black and white photograph. © Rose Hartman

-

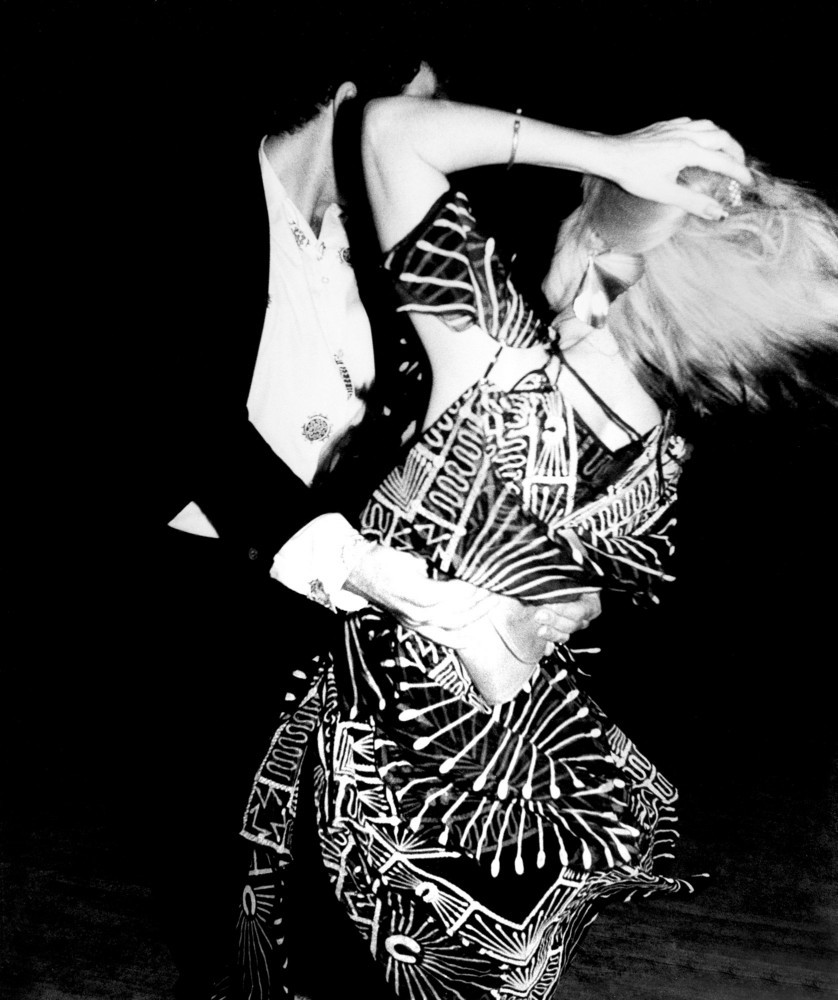

Dustin Pittman, Stroke of Midnight at Studio, 1978–79. © Dustin Pittman

-

Allan Tannenbaum, Fiorucci Dancers, April 26, 1977. © Allan Tannenbaum

-

Rose Hartman, Francesco Scavullo and Tina Turner, Studio 54, 1977: Black and white photograph. © Rose Hartman

-

Rose Hartman, Bethann Hardison, Daniela Morera, and Stephen Burrows at Studio 54, 1978: Black and white photograph. © Rose Hartman

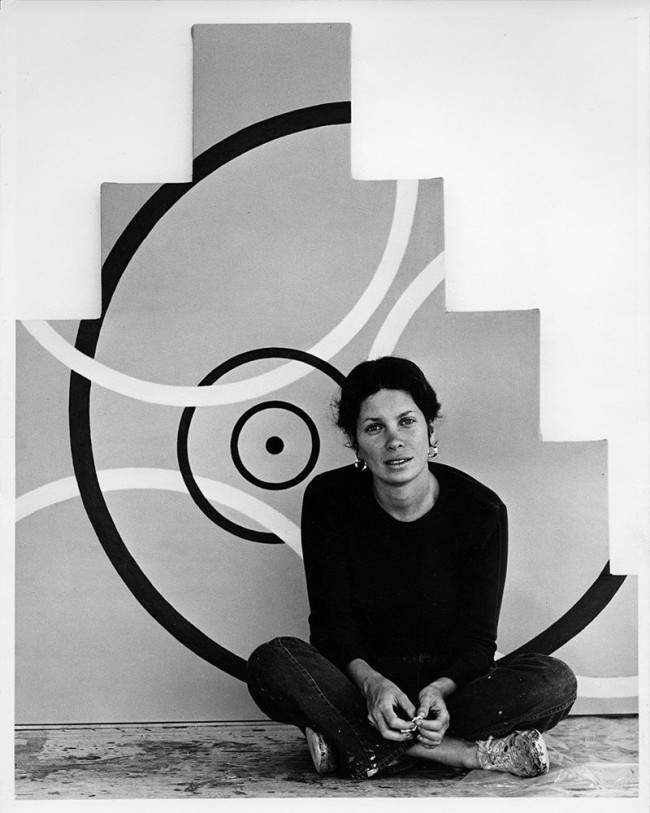

For that, a visit to Spring/Break art fair was in order. Home, an installation at Marisa Newman Projects, was the first part of an ongoing project by Georgian-born, Brooklyn-based visual artist Levan Mindiashvili called Levani’s Room, a reference to James Baldwin’s novel of queer love in a rented room told into a mirror. Within walls curtained by a print of his own room in Bushwick, Mindiashvili fixed steel frames displaying logos of iconic queer parties he’d made himself at home in, each painted in liquid mirror on glass. In effect, he created a hall of mirrors in which every reflection is self-representation, proof of a larger community beyond the curtains. Then, with co-curator Arthur Kozlovkis, he turned that hall into an echo chamber of raves past, with speakers broadcasting treasured sets he’d danced to over the years; future ones via commissioned sets from Brooklyn’s finest; and even a party for Spring/Break itself, courtesy of a bespoke wristband that granted entrance to techno innovator Derrick May’s party at a club called the Basement, in Queens.

-

Home by Levan Miniashvili is part of a larger series called Levani’s Room, a reference to James Baldwin’s 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room. Courtesy Marisa Newman Projects, New York

-

Home, an installation by Levan Miniashvili for Marisa Newman Projects / SPRING/BREAK Art Show NY, 2020. Courtesy Marisa Newman Projects, New York

-

Levan Mindiashvili filled a replica of his apartment with flyers and logos of queer parties hand-painted on glass in steel frames. Courtesy Marisa Newman Projects, New York

-

Levan Mindiashvili’s installation Home included a real-size print of his room on a sheer curtain. Courtesy Marisa Newman Projects, New York

And then, of course, the city came out of its reverie and blinked in the bright light of a pandemic. Mindiashvili had spent weeks recreating his own apartment as art; now he’d have to create art in his apartment. So do we all. The Design Museum, Dia Beacon, and the Brooklyn Museum are indefinitely closed as are all the clubs which so vibrantly served as their inspiration. The party, for the moment, has gone home.

Text by Jesse Dorris.

Images courtesy Brooklyn Museum; Dia Beacon; Marisa Newman Projects, New York; The Design Museum, London.