Material Promiscuity: Objects USA and the Evolution of American Craft

In the half-century since it opened in 1969, the exhibition Objects: USA has come to define a certain shift in American design. Enthusiastically curated by gallerist Lee Nordness and New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts and Design) director Paul J. Smith, the show brought to international attention a domestic group of talents — George Nakashima, Lenore Tawney, Wendell Castle, Art Smith — who made sculptures into seating and tapestries into textiles, or was it the other way around? The show, and particularly its landmark catalogue, profitably blurred lines between art and craft, artist and artisan. An object could “work” and still be a work of art. Oscar Wilde may have argued that “all art is quite useless,” but perhaps one could make a fine thing and still sit on it.

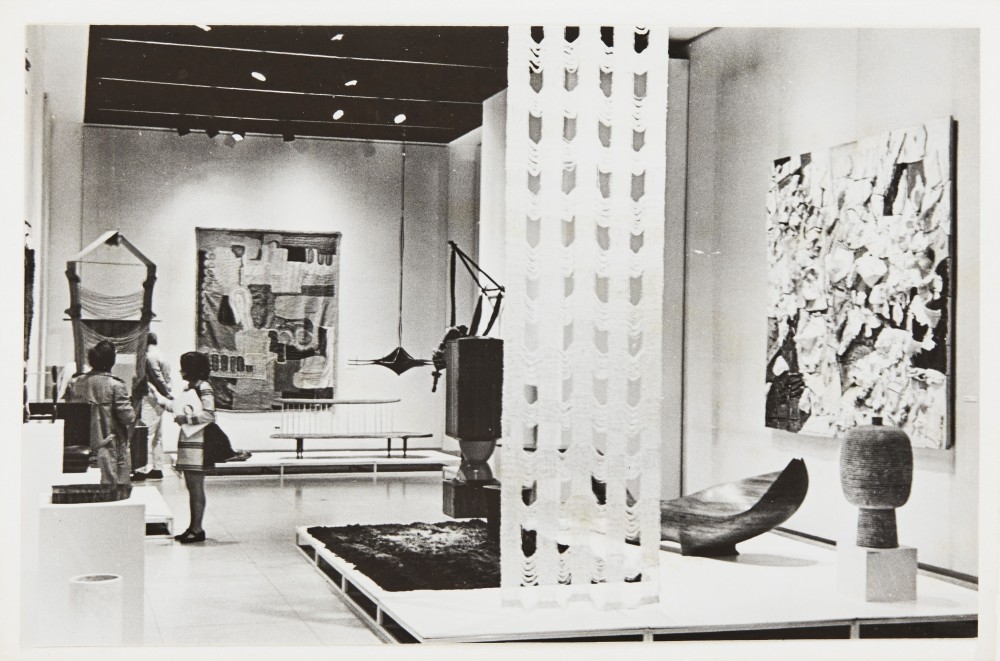

-

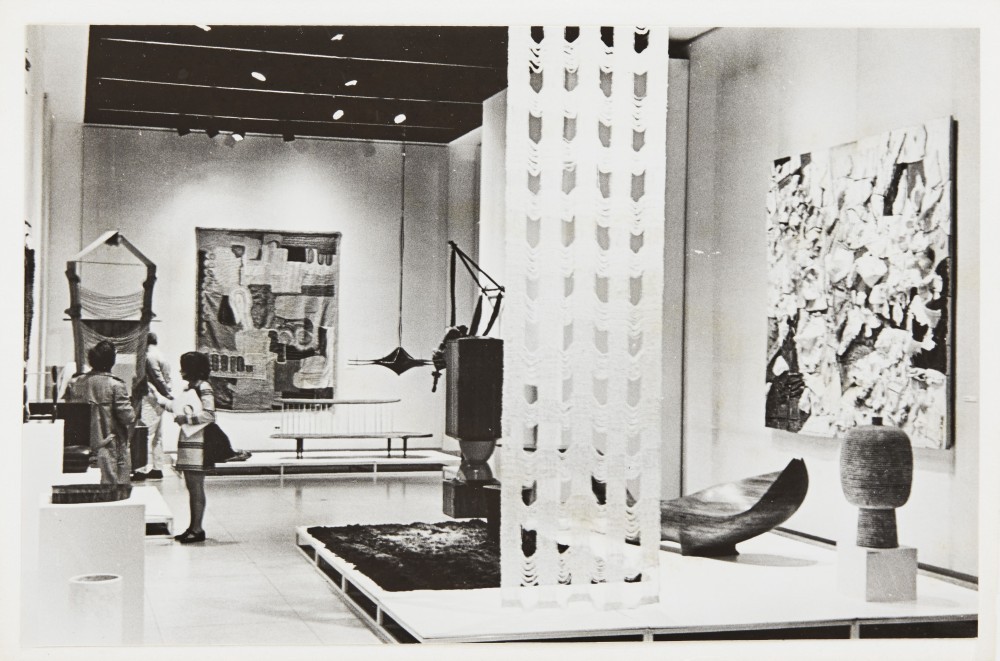

Exhibition views of the original Objects: USA show in 1969 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum from a photo album from the Estate of Margret Craver. Courtesy of R & Company.

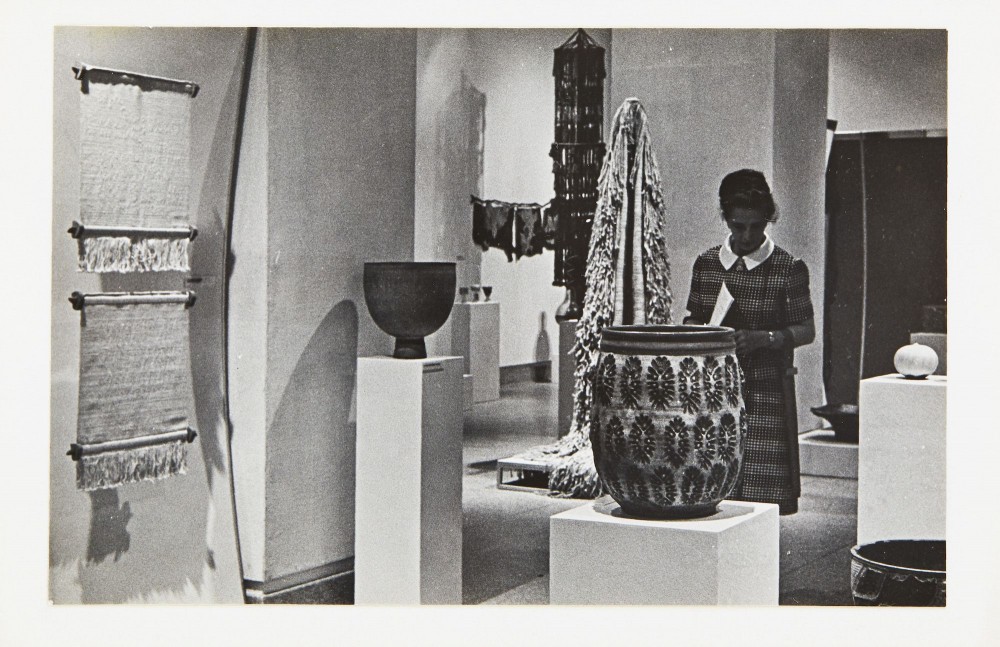

-

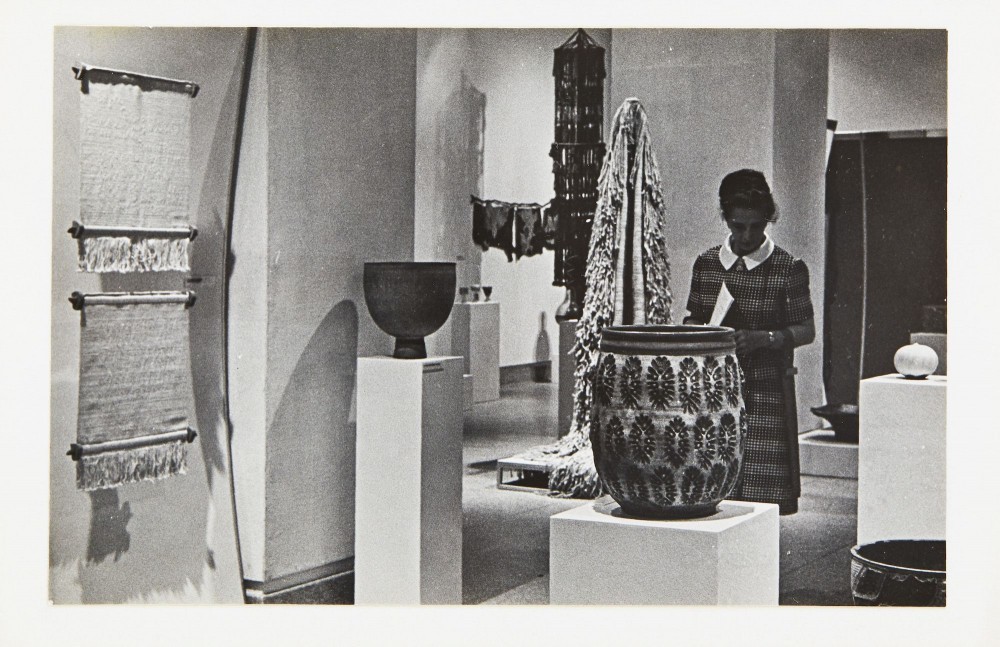

Exhibition views of the original Objects: USA show in 1969 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum from a photo album from the Estate of Margret Craver. Courtesy of R & Company.

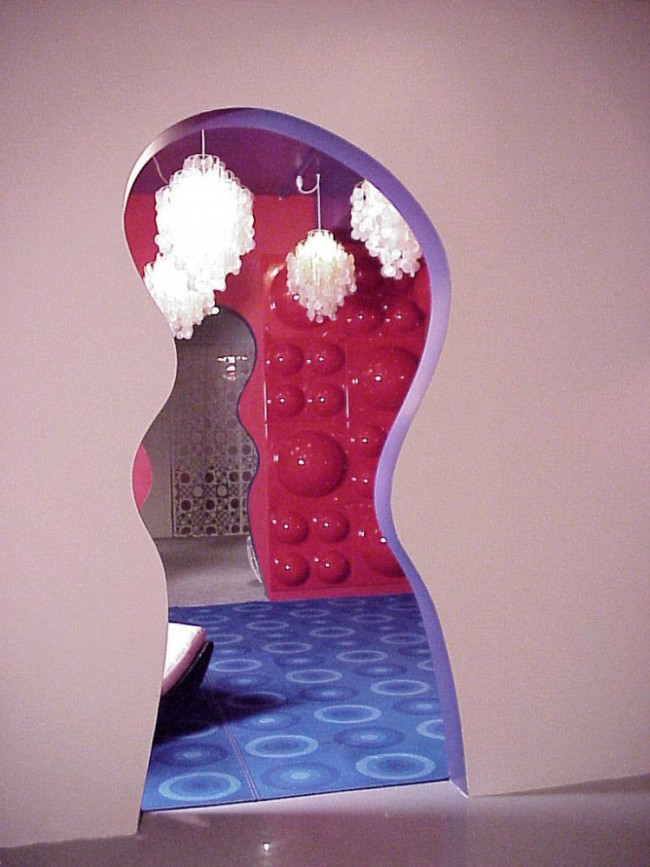

-

Exhibition views of the original Objects: USA show in 1969 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum from a photo album from the Estate of Margret Craver. Courtesy of R & Company.

With their 21st-century reprise Objects: USA 2020, on view at R & Company gallery through September 2021, curators Glenn Adamson, James Zemaitis, Abby Bangser, and Evan Snyderman are reframing the history, present, and future of what they call “handmade American arts.” The show is chockablock with blockbuster pieces, mixing work included in the original show with new pieces by new establishment figures like Katie Stout, the Haas Brothers, and Roberto Lugo. R & Company’s two-floor SoHo gallery is packed to the rafters, literally: an ethereal indigo textile by Rowland Ricketts floats above the ground floor, and Jill Platner’s monumental steel River flows from a massive hook on the ceiling and pools on the gallery’s lower level. The original Objects: USA show was both argument and advertisement. “Family company” S.C. Johnson manufactured Raid and OFF! and also sponsored the exhibition and catalogue; a 1970 ABC special, With These Hands: The Rebirth of the American Craftsman featuring Peter Voulkos flexing his muscles, artistic and otherwise; and a sales catalogue, arts/objects, through which anyone could order, say, a Castle for their own home through the mail. S.C. Johnson also bought the works included to donate to museums’ permanent collections; Smith would have the first pick for his MCC. And so Objects: USA sought to establish value in all senses of the word for crafts and those we would soon begin to designate “makers.” The catalogue became not just a reference guide but a blue book. Perhaps inevitably, for this is the USA, “Objects” democratized and gentrified at once.

Pamela Sabroso and Alison Siegel, Psychedelic Corn Smut in glass, wire, moldable epoxy, thread, and synthetic hair. Designed and made in the USA, 2020. Photograph by Joe Kramm, courtesy of the artists and Heller Gallery.

“When I started my career at Christie’s auction house in the 1990s,” the new show’s co-curator Zemaitis writes in an essay for the 2021 catalogue, the original Objects: USA catalogue “was one of our key reference books, used to establish a hierarchy of importance when appraising.” The elegant new catalogue, with its flattering artist portraits, should make appraising even easier.

Jiha Moon, Yellowave (grey), Yellowave (blonde), and Yellowave (crescent moon) in earthenware, porcelain slip, underglaze, glaze, and synthetic hair. Designed and made by Jiha Moon, USA, 2019. Photograph by Joe Kramm, courtesy of the artist and Mindy Solomon Gallery.

Nordness et al grouped the original show by material, from enamel to fiber, highlighting the dignity and potential of any kind of matter. The 2021 iteration perhaps rightly asserts that today’s artists mix media naturally. We’ve left behind the notion that an artist shouldn’t engage with the marketplace (or at least the notion that we should pretend as such) just as assuredly we’ve discarded the notion that a woodworker shouldn’t also use clay. And so now there are two types, objects deemed by the curators historical and contemporary. “The contemporary objects in this exhibition do not derive their validity from fixed categories, but rather gather meaning to themselves,” writes Adamson in his catalogue essay. “Each establishes a context for its own interpretation.” Jes Fan’s work fits this bill with aplomb; their Systems II (2018) and Site of Cleavage(2019) make out of Depo-testosterone and ceramic potential allusions to plumbing or relief panels, but feel fully sui generis. Yet Objects: USA 2020 situates them as “contemporary” in opposition to, say, old Robert Arneson’s “Alice House Wall,” an eye-popping pile of polychromed earthenware made in 1967 but utterly self-defining and fresh as a daisy blooming in the flower pots to which it obliquely might nod.

Exhibition view of Objects: USA at R & Company, featuring works by Adam Silverman, Wendell Castle, Jeff Zimmerman, Art Carpenter, Kiva Motnyk, and others. Photograph by Joe Kramm, courtesy of R & Company.

Which is all to say that this framework might lead one to think Objects: USA 2020 is less concerned with its precedent’s argument than its advertisement. Luam Melake’s mind-fucking Listening Chair, with its impossibly brutal profile of foam, is a technical tour de force that would amaze just as hard in 1969 — but has something particular to say about what it means to sit and be sat upon. Its newness is the least interesting thing about it.

Amber Cowan, Bubble Bath in the Tunnel of Love in glass and mixed media. Designed and made in the USA, 2020. Photograph by Joe Kramm, courtesy of the artist and Heller Gallery.

“We need (objects) to think with,” Adamson writes. But what are we to think? What are we, today, to make of them? Why have artists seemed to have embraced material promiscuity, and how does the market interact with their polyamorous infatuation? In 1969, the idea that a chair is a work of art might have seemed as preposterous as an NFT. Today, “makers” and “creators” are so often asked to fabricate both piece and personae that perhaps it makes sense to avoid material specialities and focus on presence. Objects: USA 2020 fruitfully relies on the when of an object for current meaning. Will that hold? Only time (and Objects: USA 2069) will tell.

Text by Jesse Dorris

Images by R & Company

Objects: USA 2020 opens February 16 and runs through July 31, 2021 at

R & Company in New York City.