Glenn Adamson’s Favorite Objects and Things

An acquaintance of mine once said to me, “artists have about as much fun in art fairs as cattle do in a slaughterhouse.” That does seems a little overstated, but I took the point. Like most everyone else involved, I put up with the format for a chance to see people — and occasionally artworks — that I admire. When I first met Abby Bangser, then, it seemed to me she was describing what we’ve all been waiting for: an art fair with people and artworks and nothing else, except perhaps a sense of style, courtesy of Rafael de Cárdenas (whom she engaged as artistic director and to design the temporary space). No booths. No evident hierarchy. Even better, from my point of view, no boundaries observed between art, craft, and design. Called Object & Thing, this truly cross-disciplinary, new-model event is upon us (it opens this Friday), with about 200 objects, none easily categorized, all of them interesting. Here are twenty favorites. In the spirit of the thing, I’ve listed them in no particular order.

Martino Gamber, Screen #2 (2016); Linoleum, blockboard. Courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Martino Gamper (Anton Kern)

The Italian-born, British-based designer Martino Gamper is possessed of unstoppable creative force, most famously realized in his project 100 Chairs in 100 Days. He has been widely influential for his incorporation of existing elements into design, often in a way that manages to seem rudimentary and sophisticated all at once. One important implication of his work is that anyone can make brilliantly inventive objects, at relatively low cost. Gamper’s recent polychrome screens in the bargain-basement material of linoleum evoke a long history of abstraction in the format, including examples from the avant-garde artist-designers of the Omega Workshop.

-

Alexis Gautier, San Fermo della Battaglia (Zebra’s Legend) (2017); Wool (backloom handwoven wool, felted). Photo by Andy Malone. Courtesy Blue Mountain School.

-

Alexis Gautier, Stair’s Legend (Black Sheep) (2016); Wool (backloom handwoven wool, felted). Photo by Andy Malone. Courtesy Blue Mountain School.

-

Alexis Gautier, Okhaldhunga (2015); Wool (backloom handwoven wool, felted). Photo by Andy Malone. Courtesy Blue Mountain School.

-

Alexis Gautier, Village Map (Zebras, Bees, Light Purple Jackets and Stairs) (2017); Wool (backloom handwoven wool, felted). Photo by Andy Malone. Courtesy Blue Mountain School.

Alexis Gautier (Blue Mountain School)

It is a widely acknowledged fact that the roots of computers are in textiles. The loom, with its over-and-under matrix, served as the inspiration for the binary system that still underpins digital technology today. Alexis Gautier’s carpets delve into this connection, pointing to deep historical connections between weaving and encoding. The works were developed through investigations in Nepal, Italy, England and India; in each location, Gautier identified symbols associated with local stories and mythology. In Lamjung Bhujung, for example, he was told the story of “a man who climbed the village stairs holding a staircase above his head” — an Escher-like image that appears in several of his designs. Each piece is woven in strips that correspond to the width of the weaver's waist, then joined during the felting process. Gautier’s carpets were featured at the inaugural exhibition at Blue Mountain School, a collaborative space in London’s East End incorporating a range of experiential spaces: fashion viewing rooms, a kitchen and wine bar, exhibition gallery, listening rooms, and a perfume atelier.

-

Alma Allen, Not Yet Titled (2016); Bronze. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

-

Alma Allen, Not Yet Titled (2016); Bronze. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

-

Alma Allen, Not Yet Titled (2016); Bronze. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

-

Alma Allen, Not Yet Titled (2016); Stalagmite. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

-

Alma Allen, Not Yet Titled (2016); Obsidian and bronze. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

Alma Allen (Blum and Poe)

Alma Allen works across a wide range of scales and materials, from small hand-shaped works to huge robotically carved sculpture, in stone, wood, and bronze. Whatever the material conditions, his forms have a seismic and sexual dynamism. Long based in remote Joshua Tree (though now based in Mexico City), he prizes his space and time. It is instructive that he names his works Not Yet Titled, implying an open-ended embrace of material and conceptual possibility. Folds, apertures, and protuberances build into an intense animism, rooted in ancient and natural forms, yet in dialogue with our own 21st century experience of pervasive flux.

-

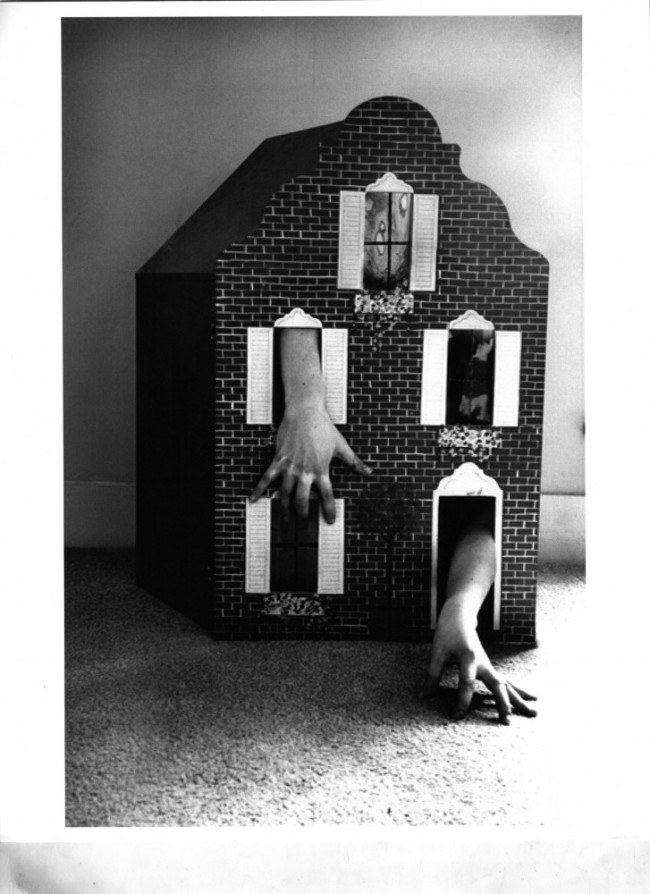

Susan Cianciolo, Game 2. WALK IN FREEDOM (2018); Cardboard, wood, acrylic paint, popsicle sticks, tape, glue, styrofoam, pen. Photo by Gregory Carideo. Copyright Susan Cianciolo. Courtesy the artist and Bridget Donahue, NYC.

-

Susan Cianciolo, Game 1. Blessed is the ONE WHO BECOMES THE TRUTH (2018); Cardboard, acrylic paint, paper, wood, glue, popsicle sticks, pen, screw. Photo by Gregory Carideo. Copyright Susan Cianciolo. Courtesy the artist and Bridget Donahue, NYC.

-

Susan Cianciolo, Game 3. UNDFEATED WAKE UP, I AM AT YOUR FEET (2018); Cardboard, acrylic paint, wood, construction paper, glue, plastic. Photo by Gregory Carideo. Copyright Susan Cianciolo. Courtesy the artist and Bridget Donahue, NYC.

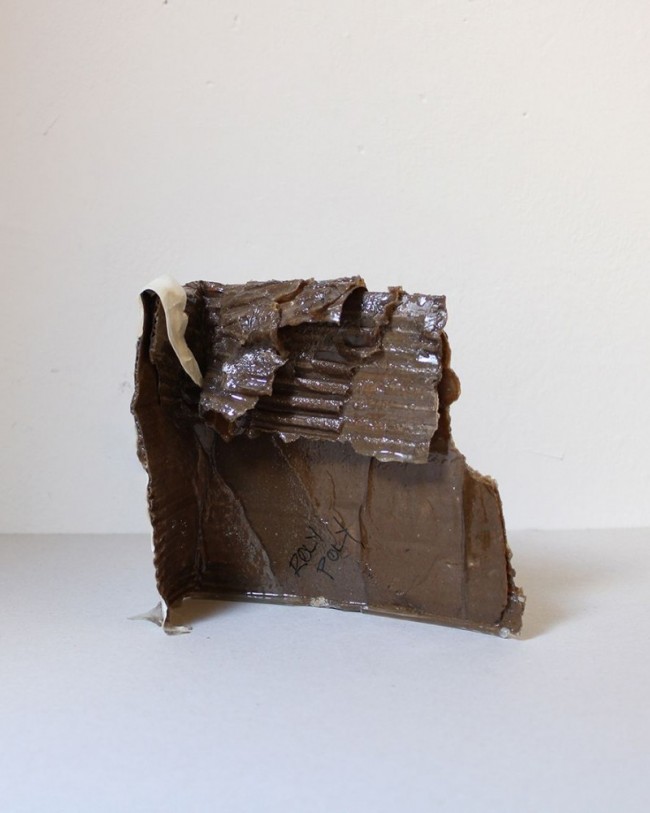

Susan Cianciolo (Bridget Donahue)

The artist Susan Cianciolo, based in New York City, knows no creative boundaries: she has made clothing, furniture, films, collages, paintings, and even a whole pop-up restaurant for the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Her multifarious approach is evident in her handmade games. Each is created from humble materialism like those a child might play with, but opens up huge mental space — a ludic microcosm.

-

Lucy Dodd, Bzzzzz B II (2018); Pigmented cotton on chair frame. Courtesy the Artist and David Lewis, New York.

-

Lucy Dodd, Bzzzzz B (2018); Pigmented cotton on chair frame. Courtesy the Artist and David Lewis, New York.

-

Lucy Dodd, Lady Long Gone (2016); Pigmented cotton on chair frame. Courtesy the Artist and David Lewis, New York.

Lucy Dodd (David Lewis)

Critic Barry Schwabsky has written of Lucy Dodd’s work that while her methods “allow for a good bit of randomness, the use of that randomness has been carefully thought through.” Dodd brings this same contradictory energy – both chaotic and precise – to her distinctive chairs, made by attaching tufts of pigmented cotton to a metal frame. The tubular understructure inevitably prompts thoughts of modernist designs, like those of Marcel Breuer, but the bright color and soft texture are more like something from the repertoire of Jim Henson. The combination is wacky and charming, yet aggressive, establishing Dodd’s furniture as the equal of her celebrated paintings and installation art.

Nagatoshi Onishi, Abalone Round Box (2006); Kanshitsu, clay, hemp, lacquer base, abalone, gold Leaf. Photo by Poul Ober. Courtesy de Vera.

Nagatoshi Onishi (De Vera)

In this small yet visually majestic sphere, Japanese lacquer master Nagatoshi Onishi updates traditional decorative materials (notably abalone shell and gold leaf) to cosmic effect. The piece is built using the kanshitsu technique — layers of cloth molded with lacquer — which allows him to shape his pieces completely, unlike many lacquer artists who depend on a woodworker to make the substrate of the work. Onishi has been a pivotal figure in the craft revival of postwar Japan, helping to establish the Lacquer Craft Group and World Urushi Culture Council, and serving as an ambassador for the medium both domestically and abroad.

Erez Nevi Pana, Wasted (II) (2017); Bamboo, cashew. Photo by Daniel Kukla. Courtesy Friedman Benda and Erez Nevi Pana.

Erez Nevi Pana (Friedman Benda)

Nearly every designer working today is well aware of impending climate change. Very few are responding in a way commensurate with the scale of the crisis. For Erez Nevi Pana, the most important question for designers today (perhaps the only truly important question) is how to produce objects that are truly sustainable, a principle that has guided all his efforts. This basket exemplifies his approach: Nevi Pana used his own personal trash as an armature for the construction of bamboo baskets. The dark “glaze” is also a waste material, sourced from the Indian cashew nut processing industry.

Green River Project LLC, Ebony Chair (2019); Ebony and boiled linseed oil. Copyright The Artist. Courtesy Green River Projects.

Green River Project

Founded in 2017 by Aaron Aujla and Benjamin Bloomstein, Green River Project is a research-driven furniture producer based in New York City. In a short time they have been remarkably prolific, exploring a wide range of sustainably sourced materials and forms with echoes of modern masters like Frank Lloyd Wright and Gerrit Rietveld. This new chair in ebony, their first design in the dark tropical hardwood, features thickly-dimensioned intersecting planes and a rich linseed oil finish, resulting in powerfully concentrated sense of materiality. The rare wood is entirely recycled, sourced from individual collections, and here and there bears the marks of its transit through the timber distribution system.

Fausto Melotti, Coppetta (Little Bowl) (1955); Glazed polychrome ceramics. Photo by Todd-White Art Photography. Courtesy of Hauser and Wirth.

Fausto Melotti (Hauser and Wirth)

Recent years have seen a reassessment of midcentury Italian ceramics, a field whose contributions to the larger project of modernist abstraction was long overlooked. Alongside the ceramic production of Lucio Fontana, there has also been a reappraisal of lesser-known figures like Fausto Melotti. He connected early in his career with the great designer Giò Ponti, then the artistic director for the ceramic factory Ricardo Ginori, and remained involved with the medium for decades, particularly in the years following World War II. This beautiful bowl engages with contemporaneous abstraction, while also conjuring the idea of a fragment of sky brought to earth.

-

Anne Marie Laureys, The Freightened One (2015); Stoneware. Courtesy the Artist and Jason Jacques Gallery.

-

Anne Marie Laureys, Scaramouche (2016); Stoneware. Courtesy the Artist and Jason Jacques Gallery.

-

Anne Marie Laureys, Untitled (2018); Stoneware. Courtesy the Artist and Jason Jacques Gallery.

Anne Marie Laureys (Jason Jacques)

There is no living ceramic artist who has a sweeter touch than Belgium’s Anne Marie Laureys — and probably only a single dead one, George Ohr. Like the famed “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” Laureys achieves a daredevil thinness in her work, working magic with its vertiginous contours. Sprayed pigment brings out the choreographed voluptuousness of the forms; orifice-like apertures yawn open, bringing to mind both the beauty of undersea formations and the vulnerable parts of the human body.

-

Rebecca Warren, Totem (e.) (2008); Hand-painted bronze on artist’s wooden pedestal. Copyright The Artist. Courtesy Demo Gallery.

-

Rebecca Warren, Totem (d.) (2008); Hand-painted bronze on artist’s wooden pedestal. Copyright The Artist. Courtesy Demo Gallery.

Rebecca Warren (Matthew Marks)

No artist working today communicates the sheer excitement of materiality more than Rebecca Warren. Though the British sculptor has explored several media, she is best known for her works in clay, which may (as here) serve as the basis for hand-painted bronze. Her baroque forms often seem caught in the act of finding themselves, at some undefined point between figuration and abstraction. Though only two feet high — modest by her standards — this example encapsulates Warren’s familiar, always thrilling, jubilance.

-

Sonia Gomes, Sem titulo (2005); Different fabrics on wire support. Courtesy Mendes Wood.

-

Sonia Gomes, Cadeira (2009); Acrylic on canvas, stitching, different fabrics on chair. Courtesy Mendes Wood.

Sonia Gomes (Mendes Wood)

Intensely handcrafted yet anarchic, the soft sculptures and objects of Sonia Gomes are made primarily of found textiles. She twists and stitches her findings into elaborate shapes, often allowing threads and strips to dangle freely. The energy of the work derives partly from the previous life that the materials had — as if the “waste stream” had been arrested and caught in a momentary creative vortex.

Ann Agee, Maid in Form II (2015); Glazed porcelain. Courtesy of the artist and PPOW, New York.

Ann Agee (PPOW)

Brooklyn artist Ann Agee works in many media, with special dedication to ceramics — she was among the first to show that this discipline could be reinvented for the 21st century. This achievement was possible because of the particular combination of historical expertise and pure pleasure that she brings to the medium. Though always cognizant of precedent, her freedom of handling and accumulative, associative approach give her work unmissable contemporaneity. In the case of Maid In Form, an upright, possibly figural form is besieged by ornaments — one might draw comparison to natural coral formations, with their boundless visual interest.

Ian McDonald, Shade Vessel (2016); Ceramic. Photo by Clemens Kois for Patrick Parrish Gallery. Courtesy Patrick Parrish Gallery.

Ian McDonald (Patrick Parrish)

At a moment when many seem to favor sloppy expressionism in ceramics, the cleanly articulated, volumetrically precise work of Ian McDonald is a welcome exception. Currently Artist in Residence in the storied ceramic department at Cranbrook Academy of Art, McDonald works with a repertoire of defined cylinder and disk forms, establishing pulsing rhythms both within each pot and across them as groups. He generally favors a restricted palette, somewhat reminiscent of the digital chiaroscuro seen in 1980s print graphics, with a hint of the subtle tonalities of the Viennese-British potter Lucie Rie.

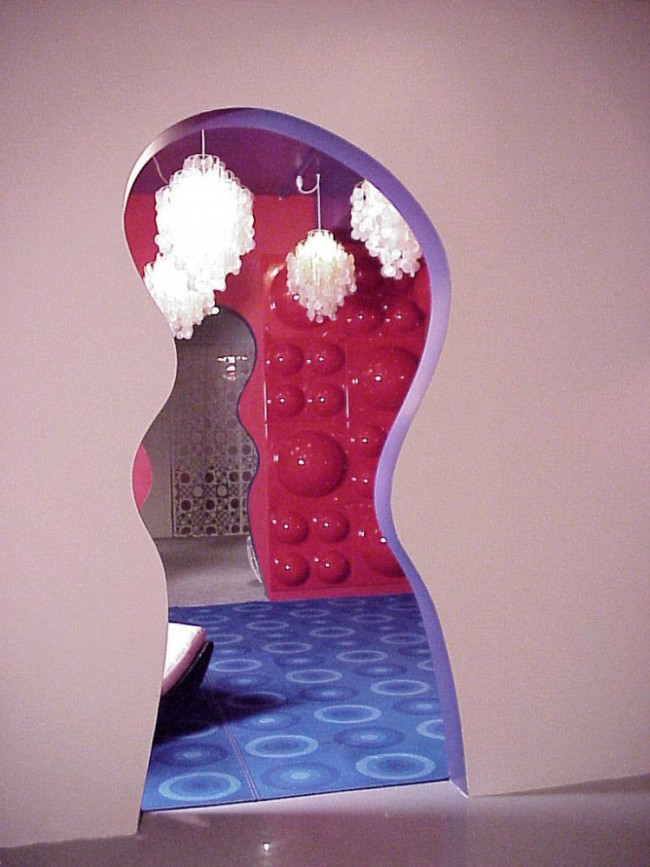

Katie Stout, Girl Mirror (2017); Unique Girl Mirror in painted ceramic. Photo courtesy Joe Kramm/R & Company. Courtesy R & Company.

Katie Stout (R & Company)

A sense of humor seems eternally underrated as a design principle – but those who doubt that it can produce truly cutting-edge work have not been paying attention to Katie Stout. Over the past few years, she has developed a distinctive iconography, alternately endearing and assertive. Her sensibility is reminiscent of the Riot Grrrl aesthetics of the 1990s, but with a Pop visuality and a contemporary Feminist viewpoint — a combination that is uniquely her own. Stout is one of the few designers working today who can legitimately be seen as the voice of the next design generation — delivered with wit, but also ringing clarity.

-

Erik Gronborg, Untitled (c. 1970s); Glazed ceramic. Photography courtesy the artist and Reform Gallery, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist and Reform Gallery, Los Angeles.

-

Erik Gronborg, Untitled (Undated); Glazed ceramic. Photography courtesy the artist and Reform Gallery, Los Angeles. Courtesy the artist and Reform Gallery, Los Angeles.

Erik Gronborg (Reform)

The Californian funk movement in clay was led by the master ironist Robert Arneson, who had many adherents. Some indulged in crass slapstick, but a few had a much finer touch, in tune with the Pop Art currents then swinging from coast to coast. One of these exponents of the style was the Swedish-born Erik Gronborg, who actually developed his style outside of Arneson’s direct influence, first studying with Voulkos and then moving down to San Diego, the other end of the state from the funk epicenter of the Bay Area). This cup is typical of his omnivorous approach to form, showing his interest in Pre-Columbian artifacts.

Liz collins & Harry Allen, Chair Chair Pair (2017); Steel and rayon jersey fabric. Photo by Jonsar Studio. Copyright The Artist. Courtesy Rossana Orlandi Gallery.

Liz Collins (Rossana Orlandi)

Thinking “outside the box” has special meaning in the textile arts, where the logic of the loom often dictates form. In the 1960s and 70s several artists (among them Françoise Grossen, who has a presence at Object & Thing) found ways to break through this creative constraint, occupying space in a new way. This history forms an important backdrop for the work of Liz Collins, a Brooklyn-based artist who has operated in several areas of textiles — fabric design, fashion, wall hangings — and exploded every one of them. The double chair seen here is a diagrammatic example of her approach. Collins ingeniously uses the metal frame of the furniture as a matrix, weaving fabric into it in a thick warp/weft structure and allowing it drape freely in between. The work creates an intriguing social situation, in which the two sitters are connected; the fact that only one chair has wheels creates a further implication that one person must be the stable center around which the other moves.

-

Gaetano Pesce, Vase #2 (2018); Resin. Courtesy Salon 94 Design.

-

Gaetano Pesce, Vase #3 (2018); Resin. Courtesy Salon 94 Design.

-

Gaetano Pesce, Vase #4 (2018); Resin. Courtesy Salon 94 Design.

-

Gaetano Pesce, Vase #6 (2018); Resin. Courtesy Salon 94 Design.

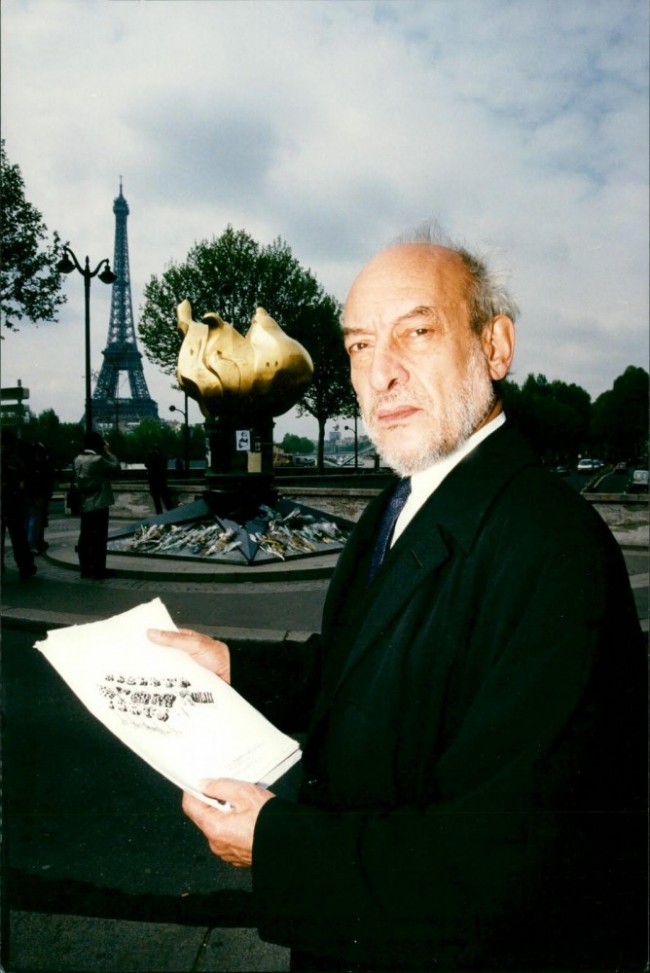

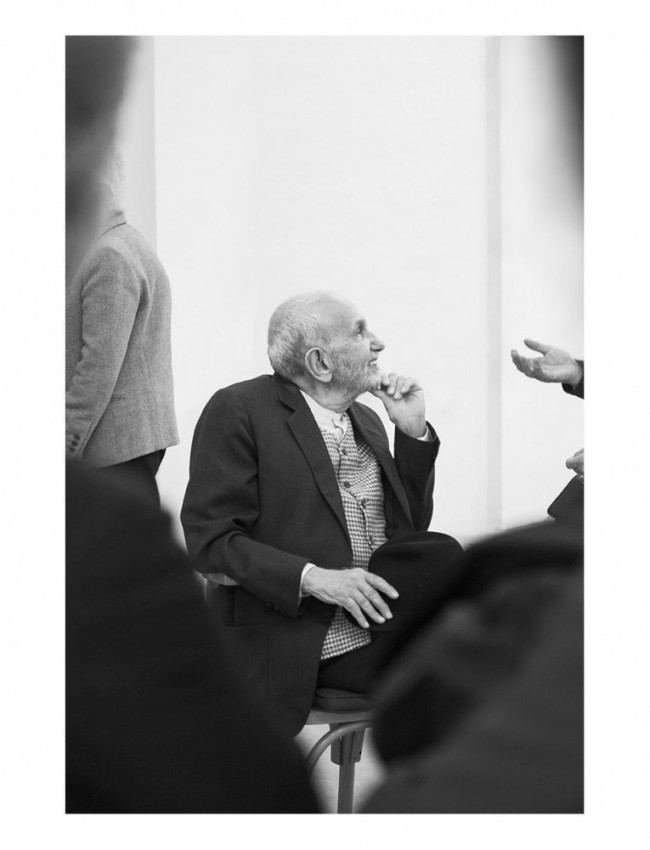

Gaetano Pesce (Salon 94)

Look around you at Object & Thing, and you’ll see the legacy of Gaetano Pesce unfolding on every side. Now in his eightieth year, the Italian provocateur extraordinaire (resident in New York since the early 1980s) continues his incessant questioning of the status quo. He has dedicated his career to the principles of constant change, anti-hierarchical fluidity, and constant experimentation. All of these qualities are evident in his long-running series of resin vases, achieved through inventive molding techniques. Each is unique, establishing itself in the world with confident individuality — emblems of Pesce’s core value of diversity in all things.

-

Alan Shields, Clops (1993); Wood beads painted with enamel paint, strung on Dacron fishing line, with artist's painted wood box. Photo by Charles Benton.Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

-

Alan Shields, Cleopatra (1993); Wood beads painted with enamel paint, strung on Dacron fishing line, with artist's painted wood box. Photo by Charles Benton.Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

-

Alan Shields, Nava Ho Pueblo Rebuild (1993); Wood beads painted with enamel paint, strung on Dacron fishing line, with artist's painted wood box. Photo by Charles Benton.Courtesy of Van Doren Waxter.

Alan Shields (Van Doren Waxter)

The three pendants included in Object & Thing present an opportunity to experience a little-known side of Alan Shields’ work. Long considered an “artist’s artist,” Shields has recently been reappraised by a broader public, who have fallen hard for his nonchalant manner, which may initially seem wayward and intuitive, but is in fact deeply considered. He had a touch with materials like no other artist of his “post-Minimalist” generation. All these qualities are abundantly present in his necklace pendants, which somehow manage to evoke both the surreal boxes of Joseph Cornell and arcade pinball games. Nor was this just a brief diversion for Shields: he had a space permanently dedicated to beadwork in his studio, and wore necklaces himself his whole life. According to gallerist Dorsey Waxter, “He took pleasure in the idea that there was a dual presentation of his necklaces, either worn or showcased in a box as indicated on the verso of the boxes. He took pride in this kind of simple invention.”

Glenn Adamson is a curator and writer who works at the intersection of craft, design history, and contemporary art. He is currently Senior Scholar at the Yale Center for British Art and the editor-at-large of The Magazine Antiques. He was Director of the Museum of Arts and Design until 2016 and is a regular contributor to Art in America, Crafts, Disegno, frieze, The Magazine Antiques, and other publications.

Text by Glenn Adamson.

All images courtesy Object & Thing.

Object & Thing will be open to the public from Friday, May 3, until Sunday, May 5, 2019.