5 PROTAGONISTS SHAPING DETROIT’S URBAN REVITALIZATION AND DESIGN COMMUNITY

Detroit has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past several years, its post-industrial blight becoming an urban laboratory for cultural experimentation. One of the reasons the Midwestern metropolis has become such a hotbed for innovation is that there’s room to take risks. Once abandoned industrial sites offer artists and designers cheap studio space as well as opportunities for large-scale installations. Plus there’s a historic design legacy in the region with some of the 20th century’s most important designers like Charles and Ray Eames getting their start at the Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Today neighborhoods like Corktown and Hamtramck are home to a thriving community of artists and small businesses. But until several years ago, most areas in the city hadn’t seen economic investment since the 1960s. One of the first developments to spur the current wave of revitalization was True North, a cluster of live-work Quonset huts designed by architect Edwin Chan and developed by Phil Kafka of Prince Concepts in 2013. Design Core Detroit has also played an important role incubating the local design community first organizing Detroit Design Festival, a week-long event which eventually grew into the annual Detroit Month of Design. In 2015 a watershed moment came with Detroit being named a UNESCO City of Design, the only U.S. city to be awarded such a designation. As Detroit continues to grow its reputation globally as a design destination, PIN–UP talked to some of the protagonists on the forefront of its changing cultural landscape, getting their insights into the city’s unique challenges, opportunities, and history.

Kiana Wenzell.

Kiana Wenzell, Design Core Detroit director of culture and community

“Design Core is a nonprofit within the College for Creative Studies (CCS) that focuses on design-driven businesses: helping them to grow, retaining them in the area, and creating market demand for design. We are fostering relationships with these designers, and now business owners are seeing the value in hiring a designer instead of doing it themselves. We're seeing the built environment improve in quality and have created around 3,000 new jobs. People like Jack Craig are staying here. Chris Schanck, a Cranbrook graduate, he stayed. I see that also with the Eames, the Saarinens, the Yamasakis, they were all Cranbrook graduates and they stayed. And Knoll, Steelcase, Herman Miller, they grew out of that. Graduates staying here has lasting impact.”

Isabella Weiss.

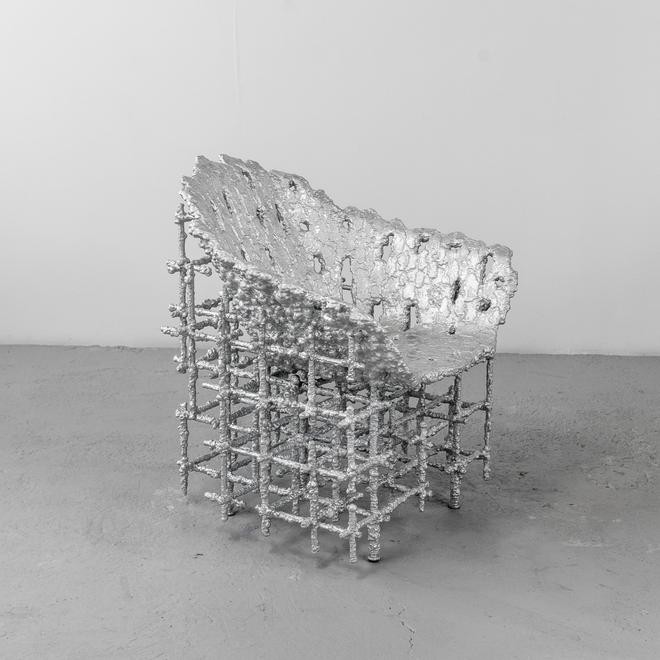

Isabelle Weiss, founder of NEXT:SPACE Gallery

“I think the main challenge is molding people's perception of value — to tell the story of why these things have value, in terms of not only the materials used, but the creative thought behind them, and the potential for what they can do for the future. That was how I came up with my exhibition plan for the year, What is the Future of Furniture? The opportunity that independent designers have to experiment with different ideas has the ability to really be the impetus for much greater change in the future — that’s always how it's been. Charles and Ray Eames, for example — Herman Miller didn't just hire them, they first experimented in their apartment with a crazy home-made machine with which they learned to steam-bend wood by hand. That was a really important part of the evolution of design in the 20th century. Period. And that mindset of experimentation is very much tied to Michigan because of the time those people spent here, at Cranbrook, and in other places in Michigan. I just find that no one really thinks about that. People don't make the correlation between where people like Florence Knoll started, and where people here today are starting. My goal is to show the next Charles and Ray Eames. But you have to present that to people in a way that they understand the history of the design that is now so iconic.”

Aleiya Lindsey.

Aleiya Lindsey, co-founder Detroit Art Week

“I live in a neighborhood that Mies van der Rohe designed in the 50s. It has a lot of negative and positive history: It was a part of a post war redevelopment program and it was built specifically for gentrification, kind of in the oldest sense. My building was built after the Vietnam War, primarily for affluent white families, but it's changed from that. It's a part of Detroit's physical makeup. It's really green. It's really beautiful. It's super diverse. The view is amazing. And it's affordable, and that's the cool thing about Detroit — you can live in a Mies without, you know, killing yourself to be there.”

Simone DeSousa.

Simone DeSousa, artist and director of Simone DeSousa Gallery

“In Detroit, there are so many areas outside the primary three areas people think about (Downtown-Midtown-Corktown), that are waiting to be invested on and reactivated while mindfully preserving the existing historic value. For example, last year, I moved from living in a loft above the gallery to another historic area in Detroit called Grandmont-Rosedale. It is only 16 minutes northwest of the gallery by car, but most people in Detroit are completely unaware of it. You could actually bike Grand River Avenue all the way from Midtown to my house, if safety conditions were in place. When you drive that avenue between those two points (Midtown and Rosedale Park), you will be astonished by the beauty and scale of some of the structures along the road, currently waiting to be activated. There is so much to do here, it is both a challenge and a possibility.”

Ron Castellano. Photo courtesy Kamp Kennedy.

Ron Castellano, Studio Castellano principal architect

“In Detroit, the goal is to not displace people. Some of the buildings we’re restoring are borderline. It would be a lot easier to knock them down, but we're trying to keep this character, and that's the architecture. But at the same time, the character of the neighborhood (is also defined by) musical history, the families, and so you don't want them to leave. People would say, in the beginning: ‘You want to buy my house? You're the developer?’ I said, ‘No! Keep your house. Stay here. Give it some time and everyone will benefit.’ The community is really what attracts me here. We’re trying to stay away from spectacles, and just create a neighborhood where you'd like to live.”

Text by Natalia Torija Nieto.

Images courtesy Design Core Detroit.