THE LEGACY OF FLORENCE KNOLL: Interview With Creative Director Dorothy Cosonas

Florence Knoll is both mid-20th-century design’s grande dame and one of its most powerful female forces. The Michigan native broke boundaries in male-dominated corporate America at a time when a woman’s workplace was considered in the kitchen, or behind a secretary desk at best. The young Florence (née Schust) first graduated from Cranbrook Academy of Art, moved on to study at the Illinois Institute of Technology (where Mies van der Rohe was her mentor) and the Architectural Association in London, before working for Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius. In the mid-1940s, when she was in her late-20s, Florence started working with Hans Knoll, the furniture manufacturer who would later become her husband. Together they transformed a sleepy mid-Western furniture manufacturer into the design stalwart that it remains today. As the company’s president and director of design Florence was also responsible for expanding the company’s focus by founding KnollTextiles, the company’s textile division. If the furniture division stood out thanks to names like Bertoia, Saarinen, and Mies van der Rohe, KnollTextiles was a laboratory of ideas by visionary female artists like Anni Albers, Naomi Raymond, and Eszter Haraszty (not to mention Knoll herself). On the occasion of KnollTextiles’s 70th anniversary and Florence Knoll’s 100th birthday, PIN–UP caught up with KnollTextiles’s current creative director Dorothy Cosonas for a browse through the archives.

Florence Knoll with her dog, Cartree, Image from Knoll Archives

You recently spent a lot of time in the Florence Knoll archives. Did you discover aspects of her work that you hadn’t known of?

When we went back into the history, we realized we look at Florence not only as a design pioneer but also as a thought leader, and a leading woman. When her husband, and Knoll founder, Hans Knoll died in 1955, she took the lead, making Knoll, and especially the textile division, a place unlike any other in corporate America. That’s remarkable even for today’s standards, but she fought that fight 70 years ago. But the post-war corporate boom in the U.S. was the perfect time to say to the world: “We’re going to create the image of what modern America, and the modern American office, should look like” — and she successfully encapsulated that spirit.

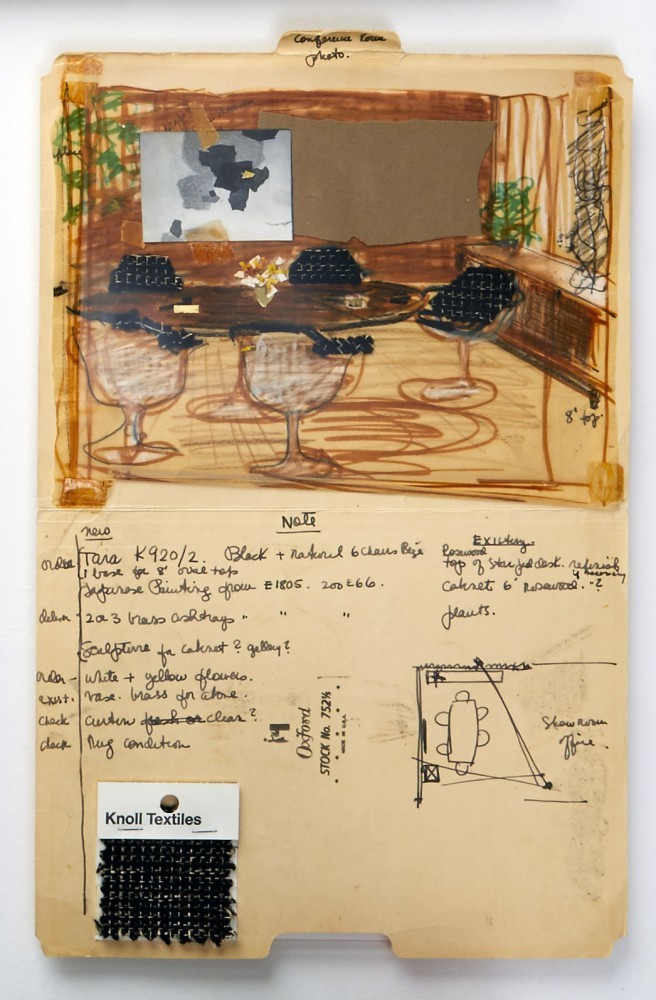

One of Florence’s most notable creations was her Planning Unit, which she started in 1946, and which worked on all aspects of interiors for a variety of corporate clients. Can you tell me more about that?

From what I can gather, Florence was a total control freak. (Laughs.) She would not only advise furniture specification, textile specification, she would also tell the clients where to place their plants, where books are to be placed, where the artwork is to be hung. She is basically giving them the integrated interior. Someone would come to Knoll as a corporate client and say: “I have ten floors,” or “I have a massive expanse of private and public areas, will Knoll not only provide the furniture but also where to place it all in the space?” That is basically what Florence and the team would do.

Florence Knoll Paste Up, 1961, office layout, from the Knoll Archives, Photographer Dean Van Dis

She would do ‘paste-ups’ — you can even see where she placed the pillows. It is almost like someone working in Hollywood. They do the plans of the movie on paper. She knows exactly what she’s going to get. Going over the history, we learned that it was her vision and it was her point of view that drove the company — as well as how she came to bring on the designers she did. It was really an A-list group of designers. There is this one photo where you see Florence in her Planning Unit. Hans, her husband, and all of these guys are there but she is the only one talking.

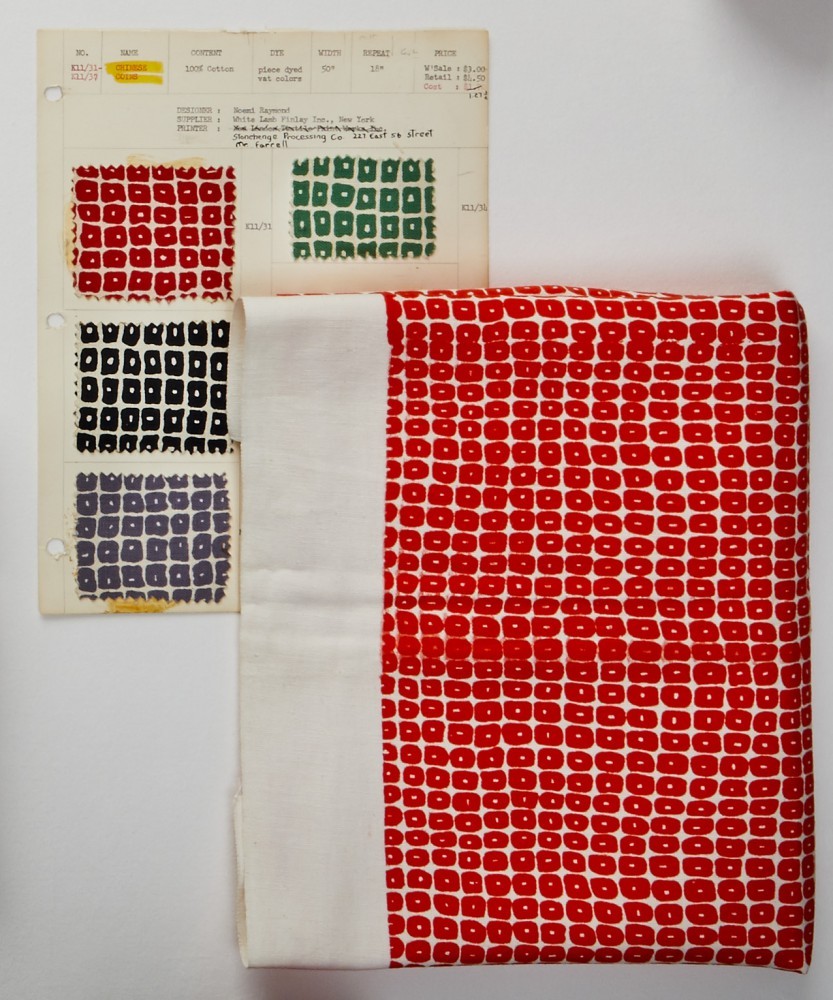

Can you tell me about some of the designers that she brought on to the KnollTextiles division?

It’s really an interesting who’s who of people that were connected to Knoll, and most of them very powerful, inspiring women: Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Eszter Haraszty, Marianne Strengell, Naomi Raymond, to name but a few. I think Florence also liked the idea of bringing in many designers to do just a small project. Anni Albers, for example, who led the weaving department at Black Mountain College from 1933 to 1949. Her 20-year collaboration with Florence resulted in Eclat, a design still current today. In today’s market, it would be really difficult to print this on linen and cotton, so we reinterpreted it ten years ago as a woven. Or take Sheila Hicks, who is still very much active in the textile world — she only did one product with Florence, the Inca textile based on her Yale thesis, but it’s been a great inspiration.

Florence Knoll's hand written notes about designers she was hiring for Textiles

Eszter Haraszty’s Fibra, is part of the permanent collection at MoMA since 1953. That tradition for me, as the creative director now, is still very much a part of who we are. In the 12 years I’ve been here I’ve worked with 12 or 13 guest designers. We follow very much Florence’s idea of finding people who are modern, forward-thinking and then to leave them to their own devices — and yet you still see the Knoll point of view, connected to their point of view, to get to the right end result. That is exactly what we do when we work with guest designers like Rodarte, Proenza Schouler, Irma Boom, Maria Cornejo, or David Adjaye.

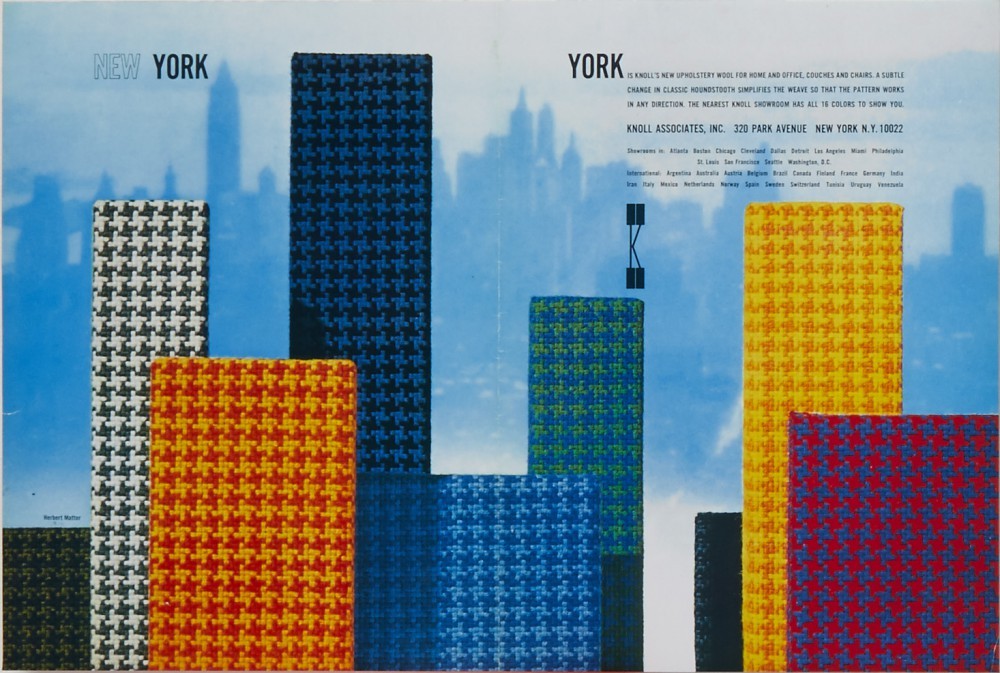

Another important aspect of Florence’s time at the helm of KnollTextiles was the collaboration with Swiss graphic designer Herbert Matter.

Yes. Theirs was a really unique relationship between. They had a 20-year working relationship, and she has once been quoted to say that no one was ever really matched his ability to do graphic design. All of the ads he designed and developed with Florence. He also developed what became known as our branding K and the “three by three” sample cuttings. Prior to coming to Knoll, he worked for a while with Vogue magazine. When you know that about him and you see his work, organic and whimsical. Where you have shape, color, and movement, his fashion background allowed a forward thinking idea for advertisement. My favorite ad is for the fabric called York for which he used the New York skyline, which I think is a simple but very smart idea of how you get someone to stop on a page, which really is what advertising is all about. Florence and Matter were very close — when she retired in the 60s, he left as well.

Advertisement for Knoll Associates, Inc designed by Herbert Matter, featuring York, 1965, next to York samples, from the Knoll Archives

The Legacy collection which you conceived for this anniversary, uses material from the years between 1945 and 65, when Florence was most involved. What is it about Florence’s work that endures to this day, some 70 years later?

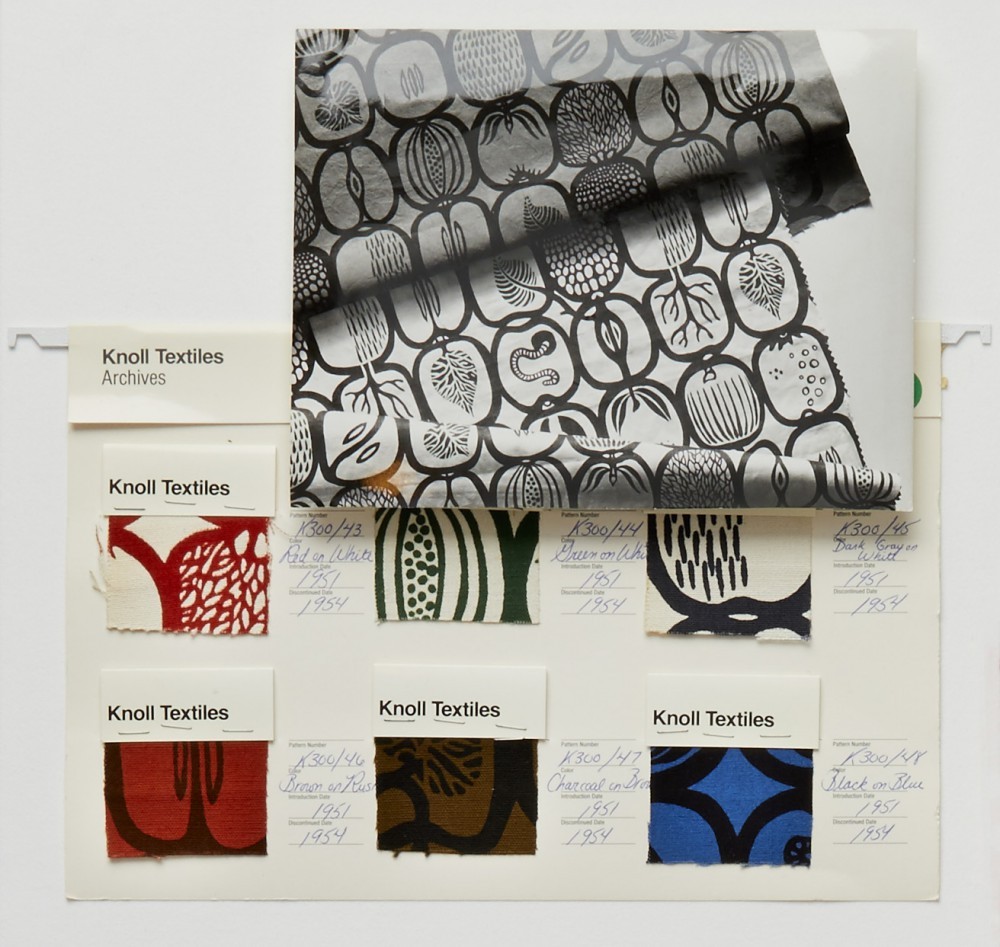

I think one of the most important things to learn from the way Florence Knoll operated is to look at how she reacted to trends. In the late 40s early 50s cabbage rose patterns on Chintzes and Damasks were very popular, both very residential and traditional motifs and textiles. Had she decided to go down that route as well, I’m not even sure Knoll Textiles would even be around anymore today. Instead her answer to that moment was to take the idea of cabbage roses, for example, and launch Apples which is a screen printed design. If you look at it and you think about a traditional idea of what a floral is, this is a complete opposite, and yet it worked.

Apples designed by Stig Lindberg in 1951 for Knoll Associates, Inc. Used for drapery; linen, jute, and cotton; plain weave, screen-printed, Photographer Dean Van Dis

So she was always reacting to things with her own ideas, which I think speaks volumes as to her vision for the company. So when we went into the archives we pulled things that we felt were inspiring or multiple ideas but not literal translations. It was important for us to do that only because we like to move the language forward, speak to our past but allow us to evolve and still have this forward thinking modern idea of what design should be. That’s how Florence Knoll did it, and that is definitely how we do things today.

Text by Natalia Torija Nieto.