INTERVIEW: Artist-Anthropologist Maya Stovall On Detroit Urbanism And Liquor Store Theatre

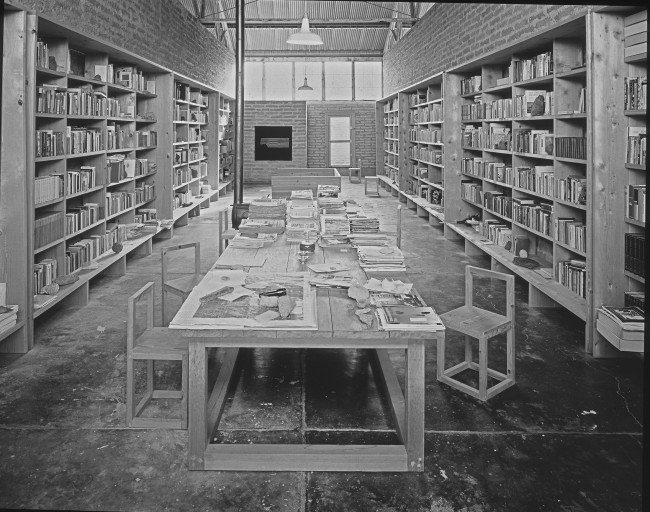

Seven years ago, Maya Stovall started dancing outside liquor stores in the McDougall-Hunt neighborhood of Detroit. Having grown up in the Motor City, Stovall understood the socio-cultural dimension of these voided spaces — the no-man’s-land of a parking lot, cracked pavement, or grassy base of a gargantuan strip mall sign — as the unofficial public squares of a neighborhood and city blighted by centuries of systemic inequity and anti-Black violence. Stuffed with overpriced snacks, drinks, dodgy electrical equipment, and sun-faded clothes, alongside the de facto offerings of beer, wine, and spirits, the McDougall-Hunt liquor stores are sites for seeing and being seen. With each conceptual performance, Stovall challenges the spectacle of a distressed neighborhood while generating a space for shared conversation. These performances, which became the basis of a video art project featured in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, as well as exhibited at the Cranbrook Museum in Detroit and the Museum of Contemporary Art Canada in Toronto (both 2018), find themselves recorded in book form as Liquor Store Theatre (Duke University Press, 2020) — but the 328-page volume, which Stovall was working on simultaneously as she was staging the choreographies, transcends mere documentation.

Stovall is an anthropologist by training, and this becomes abundantly clear in the first few pages of Liquor Store Theatre, which is meticulously researched and scintillatingly told. From a prologue that situates the project’s use of choreography as a type of ethnography, Stovall first leads the reader through five centuries of political-economic racism against African-American enslaved people in the United States. Zooming across time and into the city of Detroit, she sutures this larger history together with the institutionalized oppression that met the 1.5 million African-Americans who arrived in Detroit during the Jim Crow era: from anti-Black real estate policies and industrial job market, to the racist urban renewal plans, post-recession foreclosures, punitive credit markets, and loss of essential services like water, that disproportionately affected Detroit’s Black households, from the 20th century to now. “In Liquor Store Theatre, I toggle between the smooth and the abstract, the gritty and the material,” says Stovall, “in order to document, historicize, and ultimately, to transform.”

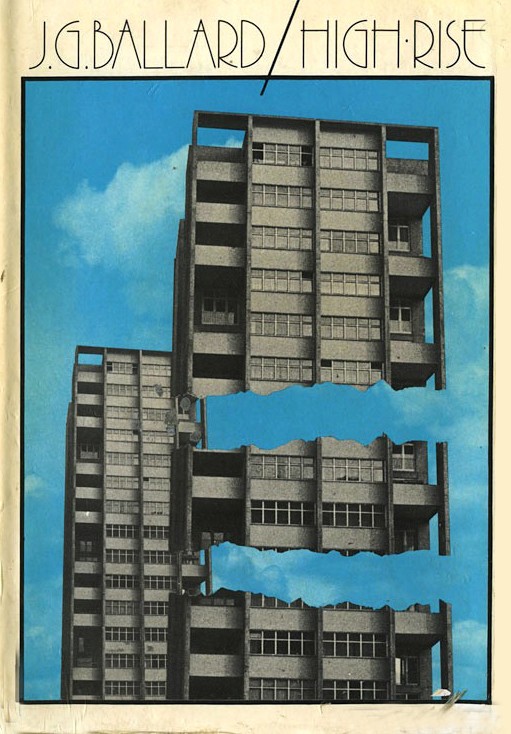

Liquor Store Theatre by Maya Stovall (Duke University Press, 2020).

The introduction brings us into the heart of Liquor Store Theatre as a project that is neither conceptual art nor anthropology alone, extending beyond the reach of either discipline. Embracing critical geography theory — the idea that space does not just exist, but, as French marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre argued, it is socially produced — alongside contemporary critical, Black, queer, feminist theory — including Roderick A. Ferguson, who assesses the fetishization of low-income and Black neighborhoods as necessarily perverse in an anti-Black American conscience — Liquor Store Theatre works across multiple channels. Stovall builds on a solid history of interdisciplinary approaches to the social sciences, citing experimental anthropologists Laurence Ralph, Deborah A. Thomas, Kathleen Stewart, and Zora Neale Hurston as key influences, critical geographers like David Harvey and Edward Soja, as well as theorists of desire, affect, and everyday life. But most of all, the project is shaped by Stovall’s informants — the individuals who decided to approach her in one of the dozens of performances she staged throughout the years to strike up a conversation; strangers who, over the years, became close friends. The video recordings are just a fraction of the project.

Abandoning the ethnographic compulsion to document everything, Stovall suggests that the work of Liquor Store Theatre truly happens before the camera is switched on and after it’s switched off. The politics of setting the stage for each performance and the conversations that happened with McDougall-Hunt residents rarely made it onto the films: jittery, five-minute-long scenes that reverberate with Detroit electronica mixed by music producer Todd Stovall. The publication of Liquor Store Theatre therefore becomes a space to unpack the true depth of the project, as well as a site for exploring Stovall’s larger research methodology.

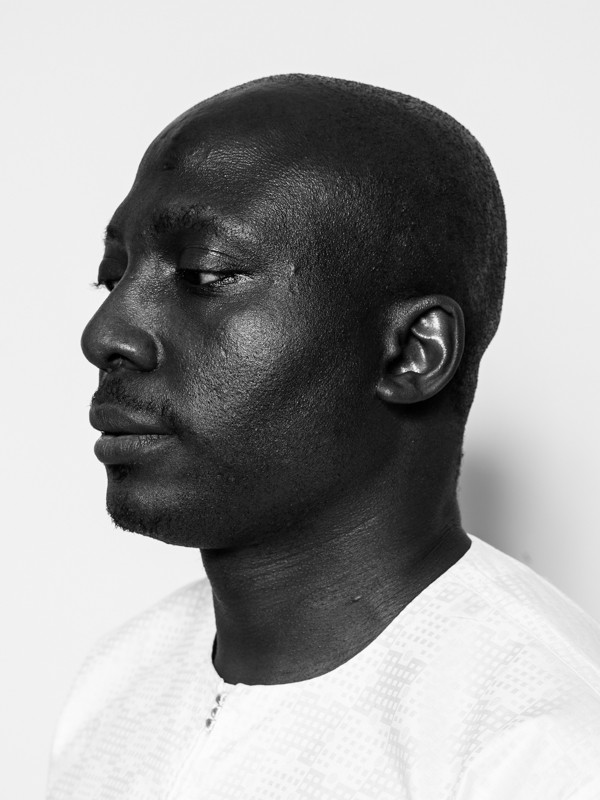

Artist-anthropologist Maya Stovall photographed by María José Govea.

Alice Bucknell: To start off, how would you describe the premise of the Liquor Store Theatre project? What informed your interest in this particular neighborhood of Detroit at this point in time?

Maya Stovall: Liquor Store Theatre is a series of conceptual performances, videos, and conversations that unfold in McDougall-Hunt, in Detroit. I was born and raised in Detroit and my interest is informed by my connection to the city, and the fact my family on my mother’s side has been in Detroit since the mid-19th century. A lot of the Detroit history this project works through is from a personal perspective — that’s a fact — but the work is fundamentally about cities, about time, about history, philosophy, political economy at scale.

Stepping back a little bit, Detroit is fundamentally an anti-Black, white suprematist city. Of course, this is the format of the U.S. at scale, in different ways through various intersecting structural forms. What I’m studying in this project is questions of power, structure, and history. I’m interested in the philosophical and metaphysical, and describe this combination of elements in the book as the “paradox of place”’: or, how seemingly paradoxical outcomes on the surfaces of cities are actually the logical — although unjust — outcomes of the way that the surface of cognition and time are structured historically.

In the publication you make reference to performance as a kind of ethnographic prompt. How do you understand the relationship between choreography and ethnography in Liquor Store Theatre?

In thinking about performance as prompt, I’m interested in this abstract and surreal point of departure to study what is happening in the city at this moment in time. What are the political-economic forces — how are power and money organized? — these are structural, historical, systemic, empirical questions. I want to get at these questions from a point of departure that’s weird, surprising, and abstracted. The position of an artist or anthropologist as extracting information from some kind of site or people or groups or subjects is an ongoing problem. Coming to terms with this problem, or using it as a framework or prompt, challenges the spectacle of a distressed economic neighborhood.

Ultimately, Liquor Store Theatre is about pushing to its limit the idea of engaging people — I don’t like to use that word — because I think this idea that there’s somehow communities that are interested and available for someone to come and insert themselves and do an act of some sort is quite presumptuous. I like to foreground that awareness with this prompt. There’s this excessiveness and absurdity of beginning a conversation with this conceptual act that I find compelling.

What’s your relationship to the project’s informants — to borrow a term from your ethnographic practice?

I don’t approach people and ask them to be interviewed for the project, ever. People view the work from the pavement and they’ll ask: what’s going on, what are you doing? Often people want to appear in the videos, or not appear in the video but want to be in the book, they just wanted to talk, and we’d talk for hours over the course of these episodes unfolding over the six seasons of this project. It’s important to point out too that the performances are a point of departure, while the discussions I’m having with people about city life continue long after the dancing stops. This is why I wrote a book simultaneously while I was developing the series of videos. So after the camera switches off, the conversations continue, sometimes for years; I’m still in touch with some of the key stars of the book to this day.

How do you feel Liquor Store Theatre challenges earlier schools of socio-cultural anthropology, such as structuralism, as well as the global image of Detroit?

Detroit’s foundational language is anti-Black whiteness: this is a historical fact that structures everyday life in Detroit. But to answer this question we need to travel way back in time — to Egypt in 3550 BCE — where we will find the oldest book in the world, The Maxims of Ptah-Hotep. It is the foundation of human reason, cognition, and moral philosophy. And in 326 BCE the library holding this book was looted by Alexander of Macedonia and Aristotle. The writings of Herodotus in the unfolding century actually refer directly to Egypt as the foundation of Greek philosophy. Speeding forward to the earliest philosophical anthropological writings emergent in Europe in the late 18th century, we see that the idea of the formation of the human is made to directly exclude people of African and indigenous heritage. There could be no greater betrayal than removing the very humans who developed the oldest and first foundations of cognition, reason, and philosophy from the idea of the human.This egregious framework is hidden in plain sight in disciplines like philosophy and anthropology and the biological sciences.

As early as 1900, Detroit’s economic system was set in stone as a particular anti-Black, white supremacist system. It’s a sophisticated and complex system in Detroit, where non-Black immigrants and non-Black POC are able to access social and economic resources rendered inaccessible to the city’s Black residents. And at the same time all POC and marginalized groups are variously oppressed and kept by the system, from forming coalitions. It’s a reflection of an algorithmic logic that works efficiently to genocide and oppress as a means to an end.

This landscape is complicated, because the liquor store is a unit model — to use an economic term — of Detroit’s anti-Black whiteness economy. The liquor stores in McDougall-Detroit do violence. They generate around 400,000 dollars per store per year. These derelict shops selling inferior goods at inflated prices to captive audiences stand in stark contrast to the average income of the neighborhood — which is 15,000 dollars per capita. Unemployment is upwards of 40 percent; being conservative, poverty in this neighborhood is upwards of 30 percent. There’s eight liquor stores in less than half a square mile — for a total annual income over three million dollars — and the patrons are 95 percent Black, while the managers are 100 percent Arab American. So this is the backdrop where jobs and the people who migrated to the city in the early 20th century are hierarchized.

Can you briefly talk about the influence of affective anthropology and critical geography to Liquor Store Theatre, and your practice more broadly?

I’m interested in the circuits and flows of a day. How these little tiny moments that make up life exist and are experienced. I have a side where I’m interested in documenting, and another side that desires to get at a feeling. To make accessible for people the experience of some feeling, to make an experience for people that hopefully leads to more questions than answers. When I write and talk I can be very detailed and analytical, and dialectical, but when I’m making work, I’m thinking about bringing out as many possible contradictions and complexities as possible, to generate people’s own affect.Each chapter of the book introduces a new liquor store scene and performance through a highly experiential narrative: from the qualities of the building, to the flow of customers, to the weather.

I’m not interested in saying, this is the affect of a person in Detroit in 2021 — I’m interested in asking the viewer to synthesize their own affect. Provoking questions and using a little moment that can validate various registers of experience or sensation or phenomenon, all could be thought of as highlighting a moment that contains an opportunity to reflect. A moment to develop our own affective experience in the world.

Why did you choose to write the opening paragraphs of each chapter in an ultra-cinematographic style?

I wanted the book to feel like a visual experience. There’s a lot of conceptual framework behind this screenplay-like treatment of text. It’s an invitation for the reader, as we move through the different segments, to occupy a macro and micro focus at same time. In the book, there is a constant juxtaposition of time as contextualized and situated, and time as immediate and urgent. I like the power that a camera has to do that in film, but I’m aware of the problematics of cinematography, and treating the screenplay as some liberating narrative force.

How do project’s recorded videos — what’s exhibited in a museum context — relate to Liquor Store Theatre in its entirety, how it’s explored in this publication?

The Liquor Store Theatre videos are just these little moments. Doing this project — researching the history, political economy, and socio-cultural landscape of Detroit, but also working through its ethnographic components — is an ongoing long-term collaboration with the city of Detroit and its residents. It’s a simmering, slow-cooking conversation with people in the neighborhood about what’s happening in this post-bankruptcy context, during a mass privatization of the commons, during increased policing and policing disparity, during a water and housing crisis.

I’m incredibly grateful for this opportunity to learn about the city through people like Greg (Winters) and the McGhees. It’s interesting to zoom out from this political-economic dialectic, and to zoom in and talk with people like Greg. He’s seen this incredible change in the city in terms of narrative and public story and positioning of Detroit — his family has been in the neighborhood since the 1950s — but he’s also seen the consistent algorithmic logic of the city and how it’s structured everyday life in Detroit’s east side. He was really interested in this art and anthropology project, what is my goal, what am I trying to do? One thing I’m trying to do is investigate that question.

As part of NADA Miami’s public programming, Reyes | Finn and White Columns co-presented a virtual book launch and panel discussion (below) to celebrate the release of Maya Stovall’s Liquor Store Theatre, December 3, 2020.

Interview by Alice Bucknell

Images courtesy Maya Stovall

Liquor Store Theatre by Maya Stovall (Duke University Press, 2020)