The Baroque Bitchiness of Pablo Bronstein

Criminally revealing without ever saying too much, Pablo Bronstein’s work oscillates like clock hands between quasi-historical parody and ironic self-awareness. Mining the depths of our apparently bottomless reverence for the architecture and design of the Western canon (as seen in the mass-produced, pseudo-luxurious aesthetic of today’s “developer architecture”), as well as his own knowledge of 17th-, 18th-, and 19th- century visual culture, Bronstein creates painstakingly detailed illustrations, installations, and choreographed performances that hold a very stylish, if slightly acerbic, mirror up to our distorted historical revisionism.

In his current double-billing eponymous exhibition at Herald St Gallery’s East and West London outposts, Bronstein bisects his signature pseudo-historical drama into objects of time and tat. Its Bethnal Green base screens Cupid’s Caprice, Bronstein’s first foray into film, and in which the artist stars as “basically being a huge cunt,” deadpans Bronstein. Staking out the tawdry outlet of a 1950s game show as setting, it’s a world of self-parody and artifice: chain-smoking showgirls bitch each other out behind-the-scenes while the stately digs of “Cupid’s palazzo” devolve into a rickety stage-set constructed within Herald St’s peeling gallery space. Blocky balustrades wiggle at the screen’s edge and film crew supplies errantly slip into view as Bronstein — playing the show host, Mercury — struts about the stage in total nonchalance. The game show, seemingly bored of itself, cycles through genres as offhandedly as its host cycles through his unaffected and sequined escorts.

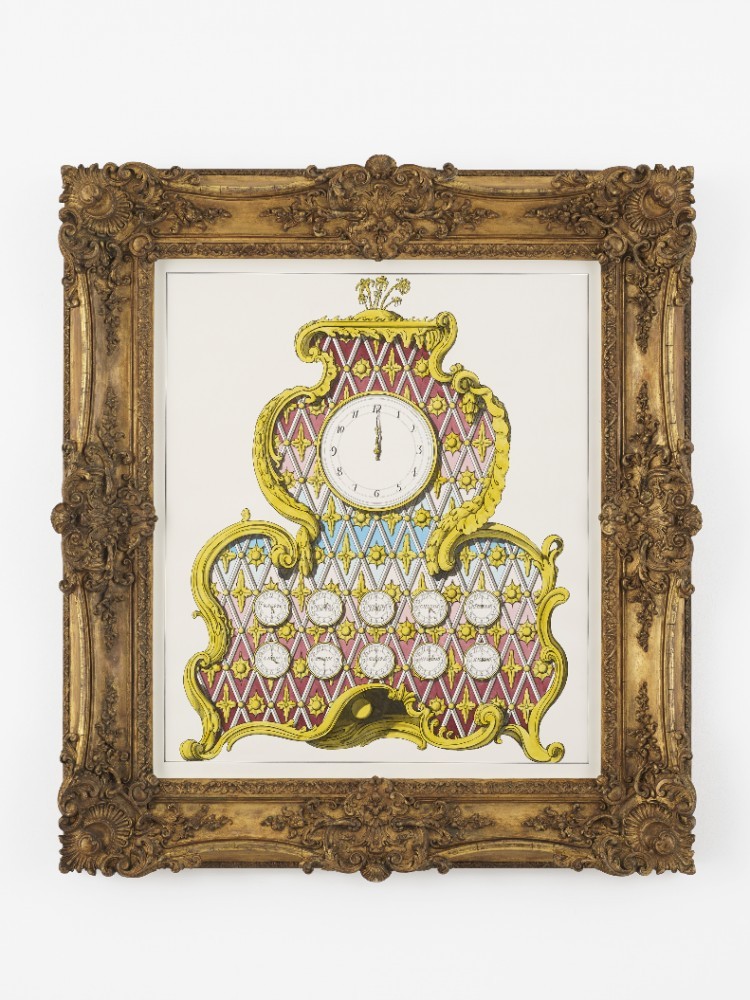

Pablo Bronstein, Greenwich Pendulum mantel clock, 2018, Ink and watercolour on paper, artist’s frame 95 x 82.5 x 8 cm / 37.4 x 32.4 x 3.1 in.

Though there’s no denying Bronstein’s excellent stage presence — a carefully calibrated ambivalence that follows him from gallery opening to dinner party — it wasn’t until the Tate Triennial in 2006 that the 40-year-old artist developed his first choreographed performance at the invitation of Tate Curator Catherine Wood. Since then, Bronstein has secured a slew of performance-based commissions, ranging from a solo exhibition at the ICA (breaking ground as the first artist to make use of its entire space), to his epic Tate Britain Commission (sponsored annually by Sotheby’s) in 2016. Titled Historical Dances in an Antique Setting, it saw Bronstein flanking the building’s Neoclassical Duveen Halls with two massive architectural screens depicting its façade, filling the space in between with a stately squad of dancers mimicking Baroque moves. Then there’s the recent RIBA commission in September 2017 titled, in all expected excess, Pablo Bronstein: Conservatism, or The Long Reign of Pseudo-Georgian Architecture.

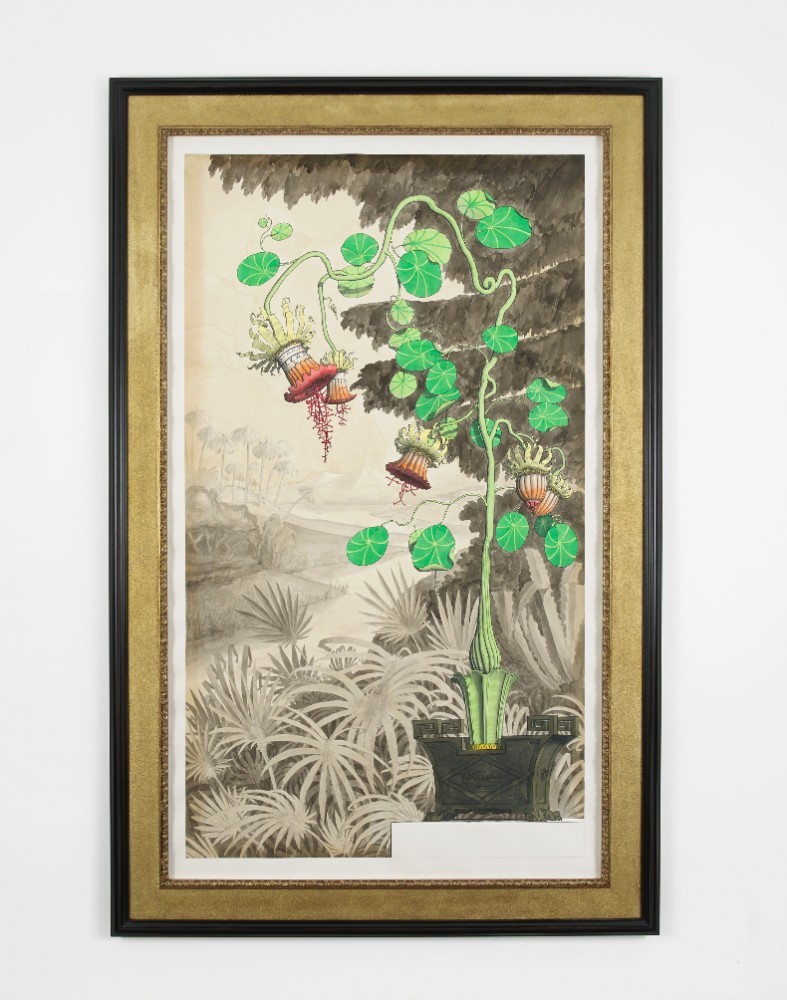

Herald St gallery’s West London outpost shows of Bronstein’s more conventional — and commercial — medium, illustration. Despite the hustle to finish this entirely new body of work (“I basically haven’t slept in four days,” Bronstein admits during the opening), the drawings show no signs of haste or self-doubt. Instead, they’re defensively dramatic, the shamelessly spliced stuff of modernist dreams and Georgian nightmares. Regency Toleware Clock in the form of a plant (2018) is a gangly ink and watercolor beast that towers menacingly over a tropical backdrop. With no architectural grid or man-made façade in sight, it’s perhaps the most unruly work in the show. The industrial heavyweight of Former world’s largest clock - Colgate Factory, Jersey City (2018) — and its overtaker, Current world’s largest clock, Mecca Royal Hotel, Mecca (2018), help lane-check the roaming tendrils of the mutant plant-clock.

Pablo Bronstein, Regency Toleware Clock in the form of a plant, 2018, Ink and watercolour on paper, artist’s frame 217.5 x 137 x 6 cm / 85.6 x 53.9 x 2.3 in.

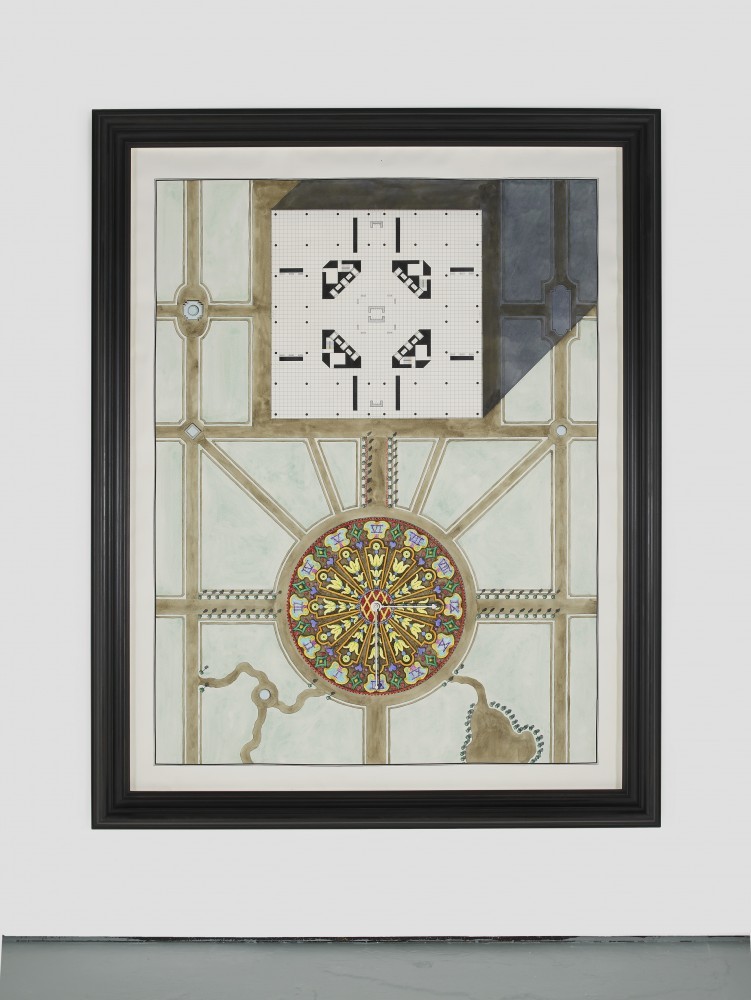

On the back wall of the gallery, Flower Clock and High Rise (2018) is a weird moment where, like Cupid’s Caprice, Bronstein’s worlds collide head-on and with little mediation, riffing off the friction. “Like Mies all mixed up with Kohn Pedersen Fox,” says Bronstein simply of the work The psychedelic “clock” is actually a municipal garden, rendered upside-down as seen from the building. “In every public park in London you would’ve once had these spectacular flower beds maintained by the government,” Bronstein states matter-of-factly, with no detectable trace of nostalgia. “Now it’s all covered in bamboo.”

What’s this? I ask, pointing to a tiny clock hiding in the corner of a Bronstein building-scape titled City Palace (2018). “Oh god, what did I draw there by accident? A Penis?” When he notices the clock, Bronstein relaxes — but only slightly. “Oh. It’s drawn at 9 AM, because some people have to turn up to work at that time, not anyone who works here, obviously…” Although Bronstein’s been painting clocks for years, this exhibition is his most explicit foray into their architectural application, a move from private to public sphere. “A clock face is essentially a painted façade, and it registers an immediate symbolic value, like Mickey Mouse or a Swastika,” Bronstein says when I ask after his interest in the object.

Pablo Bronstein, Cupid’s Caprice, 2018, Digital video, 45 mins.

No matter what medium it takes, Bronstein’s provocative practice is guaranteed to produce a broad spectrum of reactions. As source of sheer delight to those basking in the symmetrical satisfaction of his immaculately rendered buildings or the weird gaze of his omnipresent clocks, his half-imagined architectures tend to rouse a nagging tip-of-my-tongue-ism in the resident art historian or critic unable to identify these strange hybrid structures. By elevating to the same standards the ornate and bombastic with the lowbrow and bootleg, Bronstein conjures a world where high art and pop culture can riff off each other, making a parody of the whole affair. Bronstein’s latest show at Herald St hones in on these contrasts, and the result is an embarrassing, dazzling, and hilarious jostle of egos that questions our obsession with the past that makes both building and body blush.

Text by Alice Bucknell.

Pablo Bronstein is on view from 6th April - 20th May at 2 Herald St, E2 6JT and 43 Museum St, WC1A 1LY.