Book Club: Donald Judd Writings

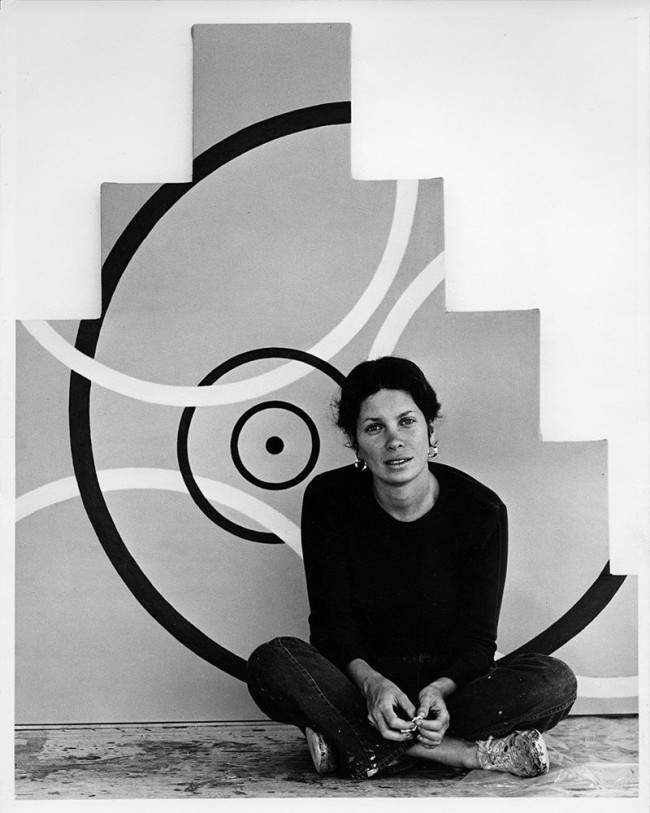

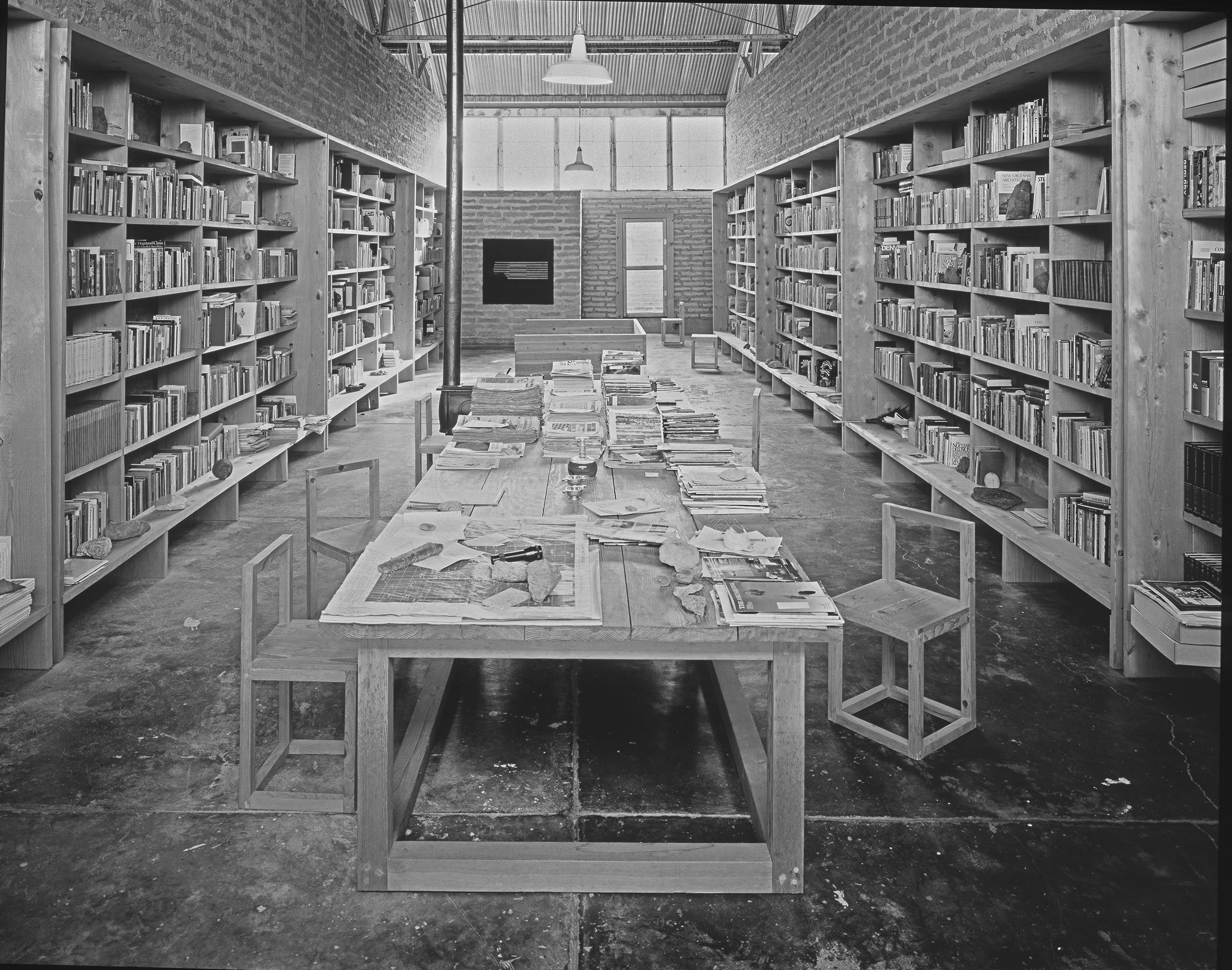

Main Library, La Mansana de Chinati/The Block, Judd Foundation, Marfa, TX © Rob Wilson, 1986

In his classic essay Specific Objects, Donald Judd described an art that is “neither painting nor sculpture,” and which “doesn’t constitute a movement, school, or style.” Judd published the text in 1965, at a time when his own body of work had only just begun to reject the conventions of gallery appropriateness. While this treatise has always been used as something of a skeleton key for interpreting his later forays into sculpture, design, and architecture, the various written works compiled in print for the first time in Donald Judd Writings offer a much broader interpretation of his legendary career. Collected here are all the works from two previous volumes, as well as graduate-school essays from Judd’s time at Columbia University, journal entries and notes that span some of his most visionary decades, and all the writing from the final years of his life, painstakingly culled from an extensive archive by the staff of the Judd Foundation.

A subtle transformation takes place in Judd’s writing that is key to interpreting his artistic work in a new light: as easy as it could have been for him to float above the tumult and upheaval of 1968 (the year he turned 40, had his sculptural works shown in a retrospective at the Whitney, and purchased the now-iconic 101 Spring Street building in Manhattan), he instead began to expand the oppositional nature of his work beyond the world of art. His essays, letters, and journal entries from this point on hardly ever fail to account in some way for the political, economic, and historical context of his projects. That he would only then begin to create works which were larger and more site specific (and difficult, if not impossible, to display in traditional arts institutions) was likely a direct result.

The concrete cubes for which Judd is perhaps best known seem to take on a different life when compounded with his private musings that the United States lost the Cold War “as thoroughly as the Russians;” that the war on drugs was “a real war against the American people;” that the reigning attitude of the left “is a veneer of virtue for the opinion of large institutions;” and that under commercialism, “(s)cience, scholarship, art, all serious activities, are mined for elements to be made superficial.” In light of the latter observation, the smooth surfaces of his most notable artworks can be read as a kind of resistance, in which the term “minimalism,” at least as far as Judd would ever be willing to avow it, is really about not offering up anything to be plundered.

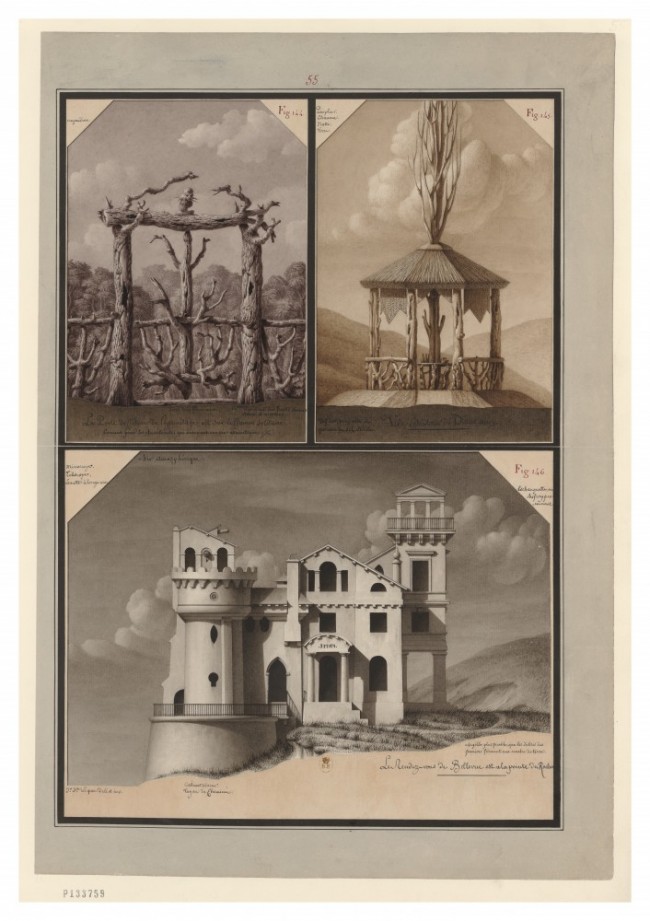

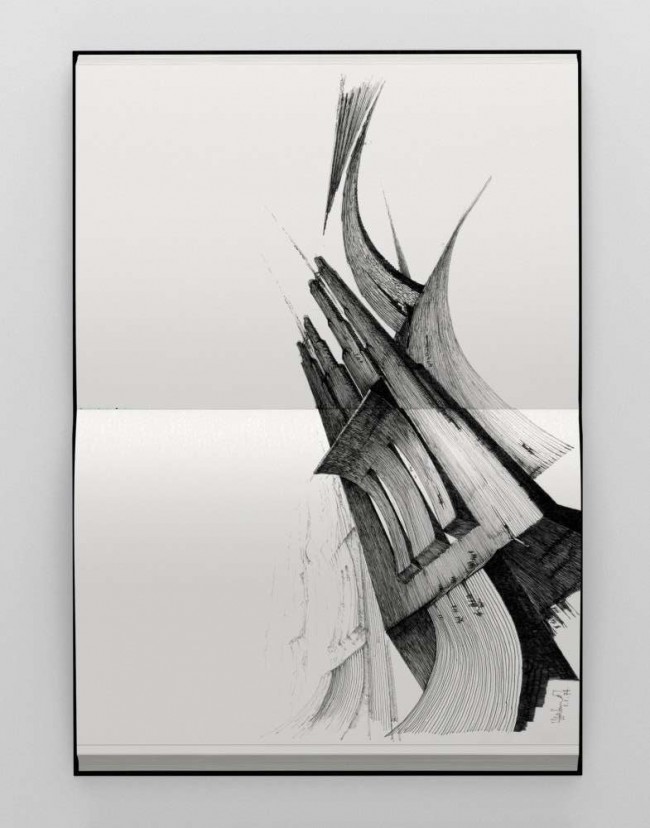

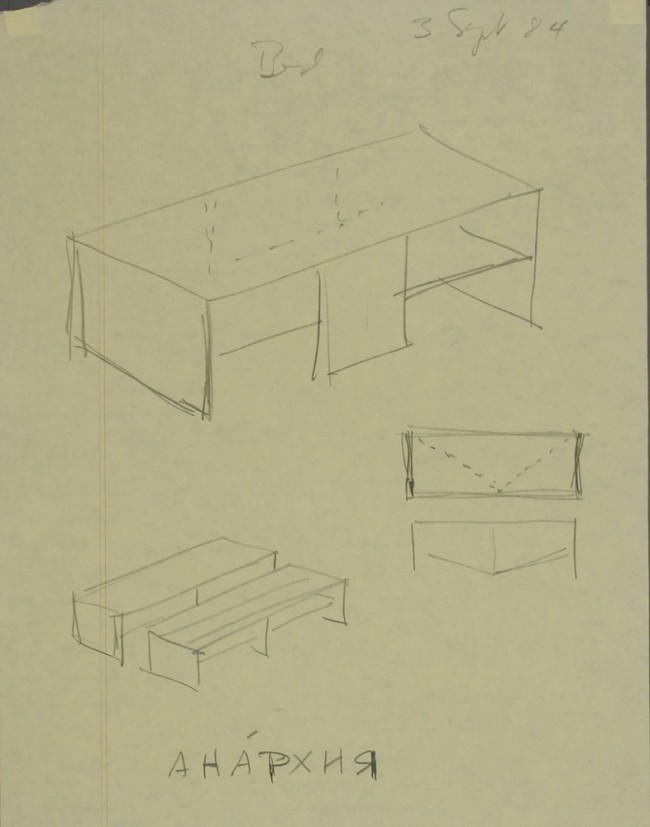

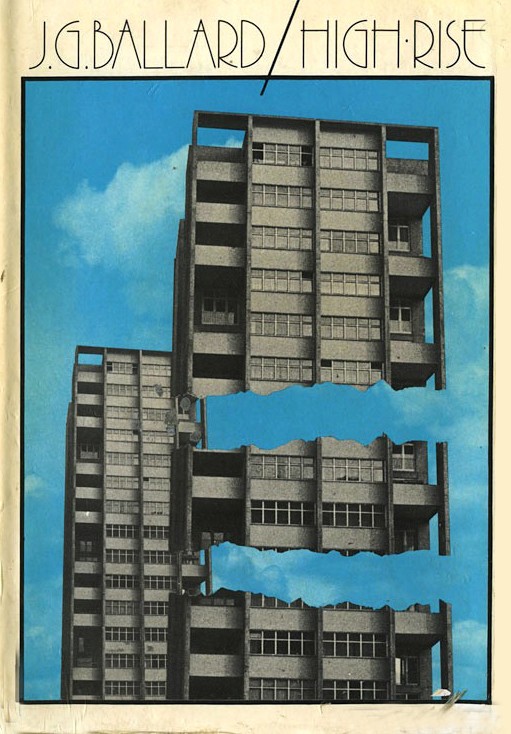

The artist’s exacting aesthetic is faithfully served by both the clear presentation and the physical construction of Donald Judd Writings. Featured in the back are nearly 200 images of his works and workplaces, pages from his notebooks, and the art and architecture of others he both criticized and admired. That such attention was paid to the details of Donald Judd’s collection as a complete object is testament to the strength of the Judd Foundation, which he created in the late 70s to “defend what I’ve done” and “make my work last.” By showing the public some of the noble ambitions behind Judd’s practice, this book does just that.

Text by Maxwell Donnewald. Donald Judd Writings, edited by Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray (Judd Foundation/David Zwirner Books, 2016).

(Left) Main Library, La Mansana de Chinati/The Block, Judd Foundation, Marfa, TX © Rob Wilson, 1986.