BOOK CLUB: HIGH-RISE

First a champagne bottle falls from one of the upper levels of the 40-floor apartment building “coloniz(ing) the sky,” where British sci-fi punk J.G. Ballard stages his 1975 novel High-Rise. Not long after, a man known only as the jeweler crashes down into the parking lot. Ballard’s cautionary tale of Modernism was recently adapted for the screen by director Ben Wheatley, and while the film version proves the story’s continued relevance, it fails to live up to the book’s perverse detail. In both versions, violent undercurrents surface in a newly-built residential tower, and as class hostilities grow, house pets become the first and last casualties of the disintegrating social order. An Afghan Hound is drowned and a white Alsatian roasted with garlic and herbs, both symbolic acts carried out by residents of the lower floors against the elites living in the higher-level units. By the novel’s end, the building’s “well-to-do professionals” have devolved into “rival clans,” the 25th-floor doctor revels in an incestuous relationship with his sister, and the tenth-floor swimming pool is littered with “skulls, bones, and dismembered limbs.”

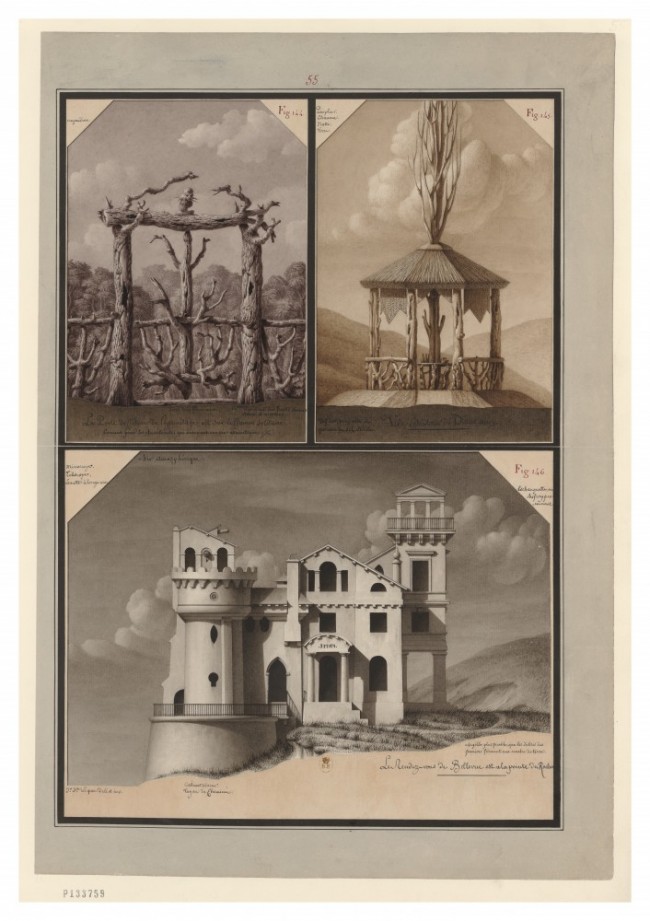

Three years before Ballard’s novel was published, a futuristic housing development known as Hulme Crescents was constructed in the British city of Manchester. The project was inspired by the “streets in the sky” ideal and the belief that modern design would result in social improvement. Just like in High-Rise, the Crescents’ infrastructure proved rushed and subpar. The lifts rarely worked. The heating system failed. Vandalism spread. In 1974, a five-year-old child fell from a top-floor balcony and died. Over the next years, the chaos amplified and the development was ultimately abandoned and demolished. Today, Hulme Crescents are recognized as one of the worst housing projects in British history and an example of the failures of so-called rational design.

In High-Rise, the building’s architect, Anthony Royal, lives in the top-floor penthouse along with his wife and dog. Early on in the novel, residents notice Royal’s “uneasy mixture of arrogance and defensiveness as if he were all too aware of the built-in flaws of this huge building he had helped design.” Royal is no exception as the tower begins to transform its tenants psychologically – he feels it’s testing him. And he’s not the only one. Men of different social classes all begin to adopt this mindset and are provoked into becoming increasingly competitive with one another. The women, however, band together — a key part of the novel entirely missing from the film adaptation — proving themselves more resilient than their male counterparts and the midwives of a new social order. By the novel’s end, Ballard’s words from an earlier chapter take on a new meaning: “This was an environment built, not for man, but for man’s absence.”

High-Rise, by J.G. Ballard (Jonathan Cape, 1975). Taken from PIN–UP No. 21, Fall Winter 2016/17.