BOOK CLUB: The Intriguing Present-Future of North Korea’s Capital Pyongyang

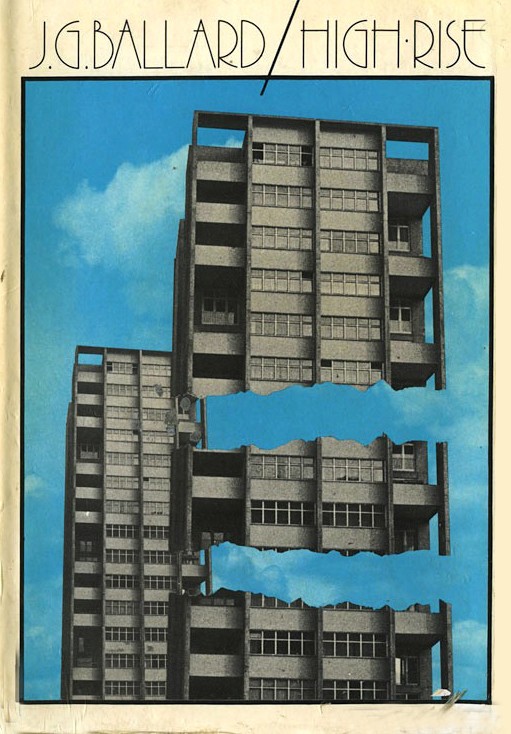

First-time visitors to Pyongyang often expect to find a lifeless gray cityscape in classic Communist style, and while it’s true that some of the older buildings evoke the repetitive prefab plattenbau housing of 1980s East Berlin (much of post-Korean War Pyongyang was rebuilt with help from architects from the German Democratic Republic), the city has been undergoing an architectural renaissance since Kim Jong-un assumed power in 2011. As a result, today’s visitors are often amazed by what they find, while those who have not been can turn to Cristiano Bianchi and Kristina Drapić’s recent book Model City Pyongyang, which is at once an architectural guide and a photographic odyssey that across 224 pages documents and elucidates both the past and the increasingly intriguing present-future of North Korea’s capital.

Central Youth Hall

Bianchi and Drapić home in on a number of essential themes that range from the dazzling — Ryomyong Street and Mirae Scientists Street, two of Kim Jong-un’s pet projects, which offer some of the country’s most colorful and idiosyncratic high-rise experiments in a weird Postmodern blend of space-age retrofuturism and neo-streamlined moderne — to the more depressing, such as a complete disregard for preserving important mid-20th-century buildings. The photographs forming the core of the book are divided into thematic sections on monumental space, “social condensers” (i.e. Soviet-style residential high-rises), icons, and the city’s latest developments. In addition to essays by Bianchi and Drapić and a preface by Pico Iyer, Nick Bonner, and Simon Cockerell of Koryo, the leading tour operator to North Korea, ruminate on the evolution of Pyongyang since 1993, while The Guardian’s architecture and design critic Oliver Wainwright considers current architectural developments in the city.

The book is supplemented with elaborate drawings, maps, and plans that also explain the grand axes that underpin Pyongyang’s urban planning, one of which runs from Mansu Hill Grand Monument to the Monument to Party Founding and another from Kim Il-sung Square to the Juche Tower. (It remains debatable among Pyongyangologists whether the third axis, which is identified by the book’s editors as running from Potong Gate to the Ryugyong Hotel, was indeed planned as such.) The city’s most iconic and controversial building is still decidedly the 1,000-foot-high, pyramidal Ryugyong, which is commonly lampooned as an aesthetic eyesore and was one of Supreme Leader Kim Il-sung’s last major vanity projects before the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. Locally, it’s still such a sore topic that it very well might have been the triggering event that led to the recent detainment of my friend Alek Sigley, whose last blog post prior to his temporary arrest was on activities around the Ryugyong and speculation that after 32 years it might finally open for business.

Ryugyong Hotel

It’s more than a little bit embarrassing that Bianchi and Drapić (as well as Iyer) quote numerous times from Kim Jong-il’s 1991 treatise On Architecture as well as from some of his son Kim Jong-un’s alleged writings on the topic. The North Korean leaders’ texts are rife with maddeningly dull tautologies and have been established as less than authoritative as well as useless in their propagandistic redundancies. These writings, translations of which are often peddled to foreigners in the country’s hotel bookshops, are clearly intended to be memorized and regurgitated; beyond that rote duty, no North Korean takes them seriously. But these are small qualms: Model City Pyongyang, for its exquisite photographic documentation alone, is an essential addition to the developing literature on visual culture in North Korea.

Text by Travis Jeppesen.

All photographs © 2019 Cristiano Bianchi.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.