GUNTA STÖLZL, UNBEWEAVABLE BAUHAUS BOSS OF TEXTILES

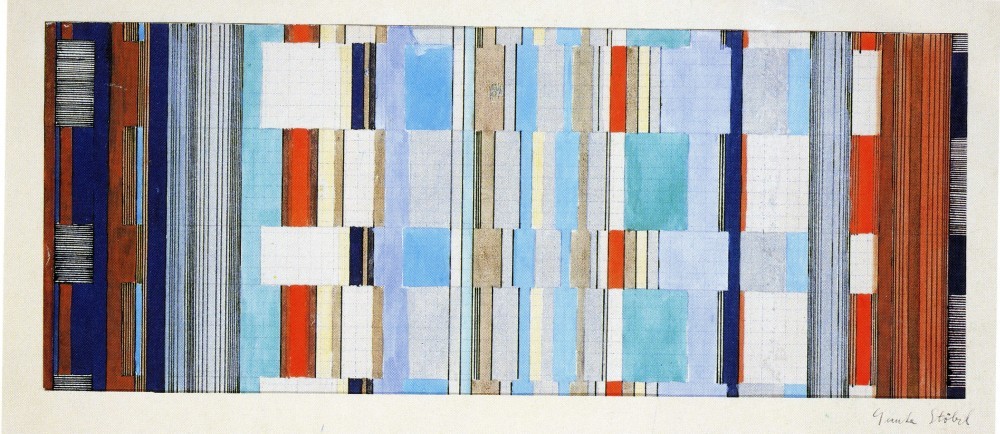

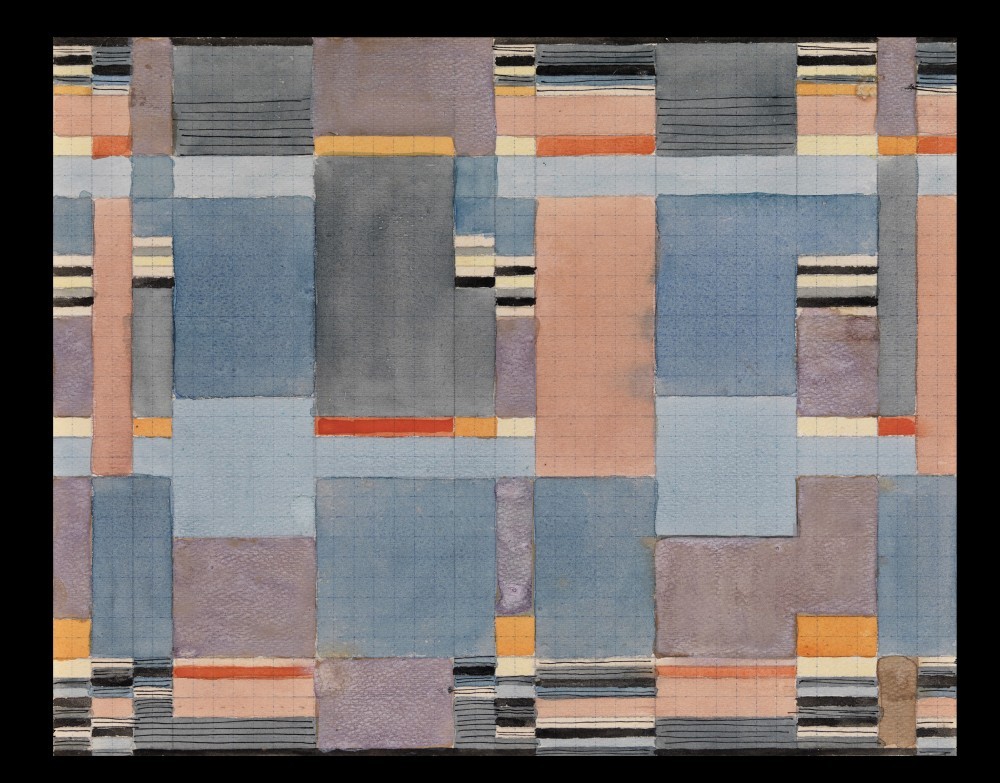

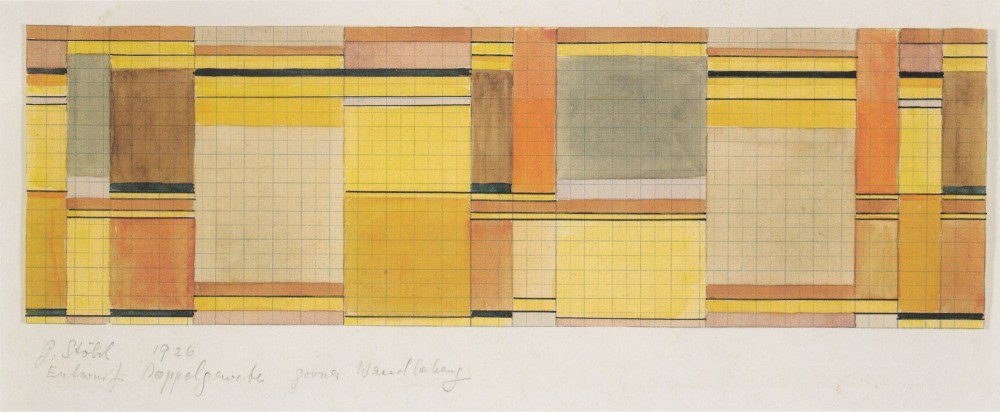

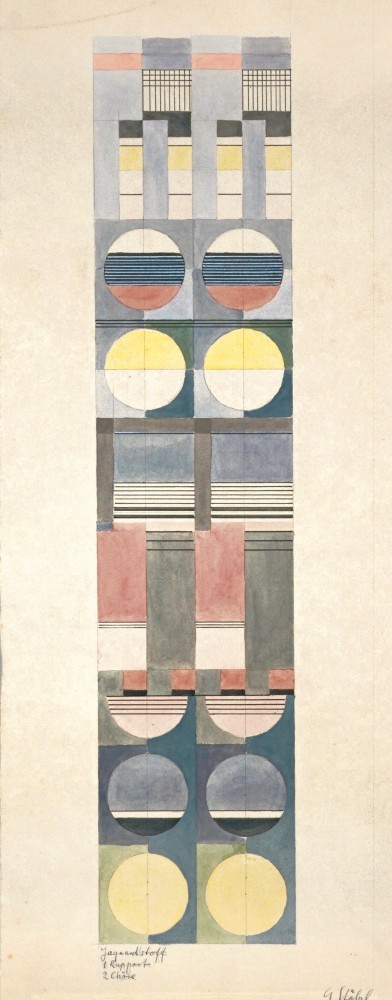

Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983) had an “almost animal feeling for textiles,” according to fellow fabric designer Anni Albers, who was Stölzl’s student in the 1920s at the Dessau Bauhaus in Germany. Albers later immigrated to the United States where she followed, together with her husband Josef, an artistic-academic path that brought her almost household-name status. Stölzl, meanwhile, pursued a quieter industrial-design career and even founded her own hand-weaving mill, but up till now has remained less well known. With the Bauhaus centennial in full swing, that all looks set to change, especially since textile company Designtex is rereleasing examples of both women’s work this year.

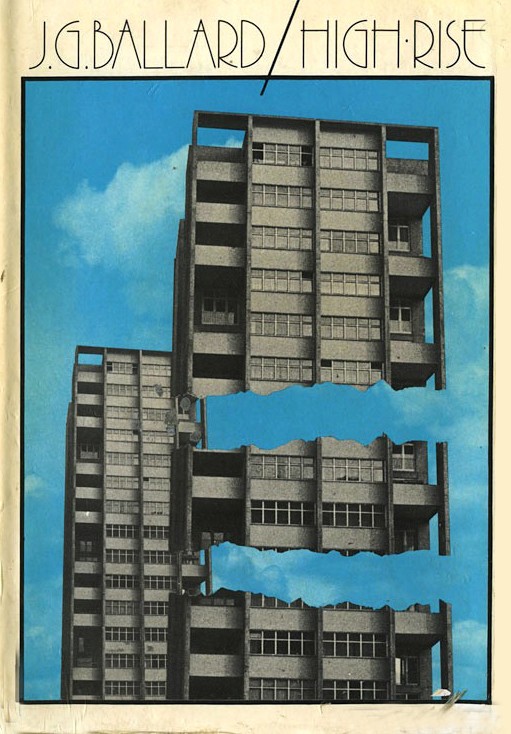

Gunta Stölzl,1929. Courtesy Stölzl Estate.

And what a story Stölzl had. Born in Munich, the daughter of a school principal, she’d already climbed mountains and been a Red Cross nurse by the time she went to study at the Weimar Bauhaus as a 22-year-old, after catching wind of the Bauhaus manifesto during a student movement for academic reform at the Munich arts-and-crafts school. Her diary entry for November 1, 1919 makes reference to Johannes Itten’s famous preliminary course: “Itten doesn’t want to teach us how to paint or draw or make art — nobody can do that. Instead he simply wants to take us to the point where we will free ourselves.” She would follow Itten to Switzerland, on graduating from the Bauhaus in 1924, to help him set up the Ontos weaving business near Zürich, but a year later returned to her alma mater — which by now had moved to Dessau — to join the teaching staff as head of the weaving workshop.

In a photo dated 1926 of all the Bauhaus “masters,” Stölzl is the only woman alongside Josef Albers, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, etc. But “master” was a title she didn’t wait for anyone to bestow upon her — she herself corrected her ID to reflect her new position, an audacious move supported by the fact she was already fulfilling the responsibilities that her titular head, Georg Muche, seemed to consider beneath him. She’d originally wanted to study painting at the Bauhaus, but female students were relegated to workshops like weaving, glassmaking, and bookbinding, which were considered women’s activities. “The irony of the situation,” explains Designtex president Susan Lyons, “is that the weaving workshop was really the embodiment of what the Bauhaus was supposed to be, taking things down to an abstract form and turning them into products.” Under Stölzl’s leadership the workshop, where prototypes for functional fabrics were designed by hand before being produced on an industrial scale, was particularly profitable — in a 1927 letter to her brother, she boasts of the “maximum number of commissions, furnishing a large café, etc.”

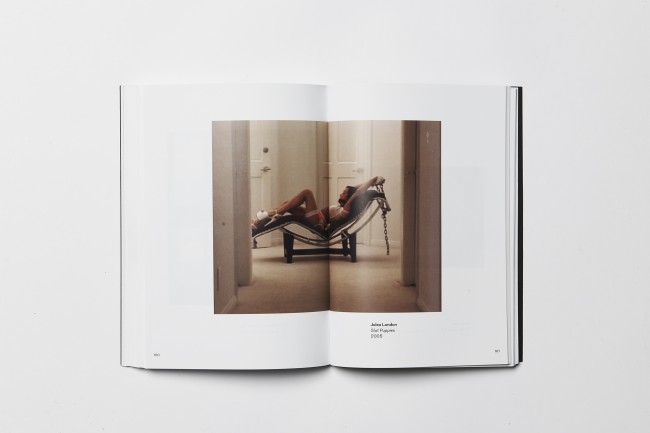

Designtex upholstery textiles inspired by Gunta Stölzl designs from their Bauhaus anniversary collection.

“She did all of this and had a kid with her,” Stölzl’s grandson, Ariel Aloni, reminds us. His mother, Yael, was born in Dessau in 1929, following Stölzl’s marriage to Jewish architect Arieh Sharon. The growing political tensions in her homeland — “They drew swastikas on her door,” Aloni recalls — eventually forced both to leave, in 1931; while Sharon went back to Palestine, Stölzl found refuge in Switzerland, where she worked hard setting up a mill whose weavers executed her designs for curtains and furniture. She later married Swiss writer and journalist Willy Stadler and had another daughter, Monika, who is now in charge of her mother’s archive. At 70, Stölzl retired from business and returned to weaving tapestries, which she exhibited and sold. “To my eyes, she worked all the time,” remembers Aloni of his grandmother, the textile pioneer. “There were always all these new Gobelins!”

Text by Whitney Mallett.

Images © Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; VG Bild-Kunst Bonn; and Stölzl Estate.

Taken from PIN–UP 26, Spring Summer 2019.