INTERVIEW: Designer Ini Archibong On Making “Three-Dimensional Poetry”

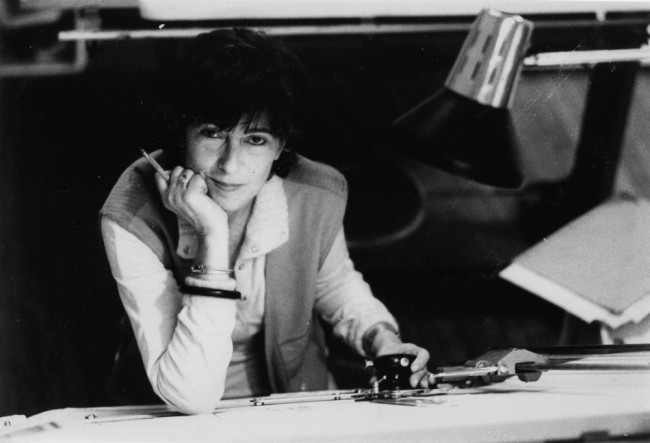

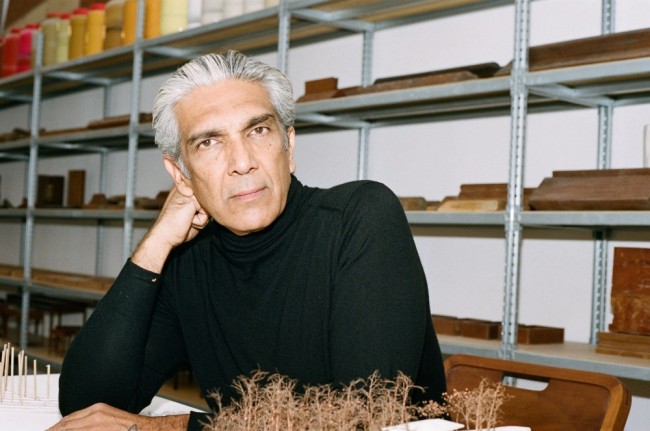

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

Upon a recent return to his native Los Angeles — to receive an alumni award from his alma mater, The ArtCenter College of Design — Ini Archibong admitted: “I’m not built for school and institutions.” After graduating with a degree in Environmental Design in 2012, Archibong, who had earlier detoured into a spiritual dead end with business school, felt he was “finally on my path” — albeit an Odyssean one, moving across continents and working between scales, negotiating his place making functional objects with an emotional dimension. The Nigerian-American designer spent several years in Singapore working at an architecture firm focused on technological advancements. “It was a good learning experience,” he says, “but obsolescence is built into anything with technological elements, and deep down, I knew I was meant to make things that last.” Archibong later received a master’s degree in luxury design and craftsmanship from École cantonale d’art de Lausanne, staying in Switzerland after graduation. Today he works from a home studio in scenic Neuchâtel. 2019 was a breakout year for Archibong, with a celebrated furniture collection, Below the Heavens, for Sé and a line of Galop watches for Hermès, as well as an installation and performance at the Dallas Museum of Art, TheOracle, which used light, sound, and dance to induce transcendent synesthesia (see video below). Nowadays he buries deep into a (yet-to-be-disclosed) new project with Knoll while continuing his collaboration with Friedman Benda Gallery in New York, creating unique sculptural design objects. PIN–UP caught up with the multidisciplinarian on the occasion of a recent talk he did at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C.

Is product design a departure from architecture?

No, because design makes me a better architect. For the most part, you consume architecture with your eyes and interact with furniture with your body and hands. When you deal with a handheld object, you get down to your fingers — your sensibility is different. When you grab a doorknob, the information your body receives includes temperature and material; it’s a fully tactile experience that differs when you’re grabbing wood versus brass. I just designed a watch (for Hermès), something you consume with the skin of your wrist, which has a different sensitivity than your hands. So, all of a sudden, all surfaces become very important and very intimate. Design is a matter of developing those intimate understandings of the different scales that occupy space. Moving down in scale gives me a deeper understanding of every aspect of what you build into a space. That’s going to make me a more informed architect someday. So, I don’t see it as a departure per se; more as an exploration. The real question is how difficult will it be for me to scale back up? How will I design a skyscraper?

Would you like to?

I can imagine doing all of it, yeah! Whether in design or architecture, you’re dealing with volumes, light, the human scale, and the body. And, ultimately, the goal is to create environments and spaces that enrich peoples’ lives — to frame and elevate their internal experiences. I view every space as a temple of some sort. It’s a temple toward whatever it’s dedicated to. So, in that sense, there’s nothing I can imagine not doing. (Laughs.)

-

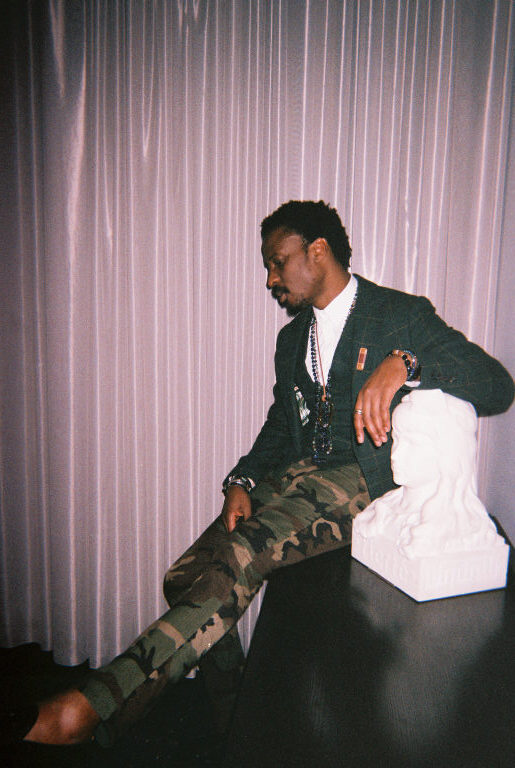

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020, posing with Gustav Siber’s Fierté, 1895. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

-

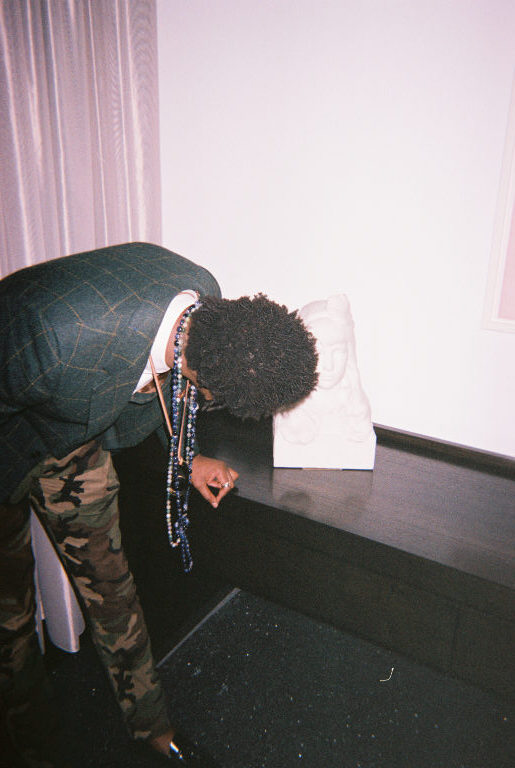

Ini Archibong gets a closer look at Gustav Siber’s Fierté, 1895 at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

In previous interviews, you’ve described your working process as transcendent or sublime — is it the object itself that’s transcendent or the process of making?

In the best-case scenario, I don’t have any memory of making until after the work is complete. I’m a bit detached from the process, and the objects are imbued with the energy flowing through me. The objects are here, though. They’re very much terrestrial: made with materials, made by hand. I’m here. I’m not a mystic floating in the nether realms. Still, I feel a reverence for the spiritual aspect of reality.

Your work process is also quite solitary: More like a fine artist in a locked room than a designer directing a team in a big studio.

Yeah, I can’t walk into a studio full of people and just (pantomimes typing) click, click, click away. It’s just me by myself, which means that as more requests come in, it’s becoming an issue that I sleep less. (Laughs.) So, I don’t have the design studio support, but I do tap into the expertise of others when needed — a glassblower, an engineer. And they could be in a different country or on a different planet. Maybe that’s just the new way of working in 2019: one of the effects of globalization is no barriers between you and the best of other craft. So, I don’t know that I need to have a centralized studio. A typical design studio is not amenable to the type of work I do.

And how would you describe the type of work you do?

It’s funny, I remember giving a talk in New York in which I referred to myself as an artist and somebody in the audience became deeply offended. They considered themselves an artist and told me: you’re a designer, it’s not the same thing; it comes from a different place. I don’t think that’s necessarily true. Labels affect some people, but not me. Fine artists don’t assume people are going to immediately understand what they put into their art. I approach design that exact same way. I put layers of meaning into any object I create, whatever it is, even an office table. A table is never just a table. You can pretend it is, but if you take that same table and put it on a museum pedestal, people will actually think about what statement you’re making. A mass-produced object can be contemplated the same way in a person’s home.

-

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020, posing with Gustav Siber’s Fierté, 1895. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

-

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

You see no discrepancy between a one-of-a-kind handmade object and something mass-produced?

The Saarinen Tulip Table: that’s mass produced, but no matter how many times you see it, you receive the same energy from it. Or the Barcelona Chair. It has a quality to it. It comes from a place of meaning. If a company is able to see value in that, they can invest in that quality and produce it for a large audience. That’s why I choose my partners very carefully because it depends who’s making it. To me, the Hermès watch I just did is mass produced: Some of the components are made by methods of mass production and the scale of how many people have access to it makes it mass, but it’s still craft. Every single one of those leather straps has care put into it — I’ve seen them being made. I’m doing a project now with Knoll, which I can’t say much about yet, but they share a certain common quality with Hermès. What I’m making with them is not just for right now. It needs to be bigger than that.

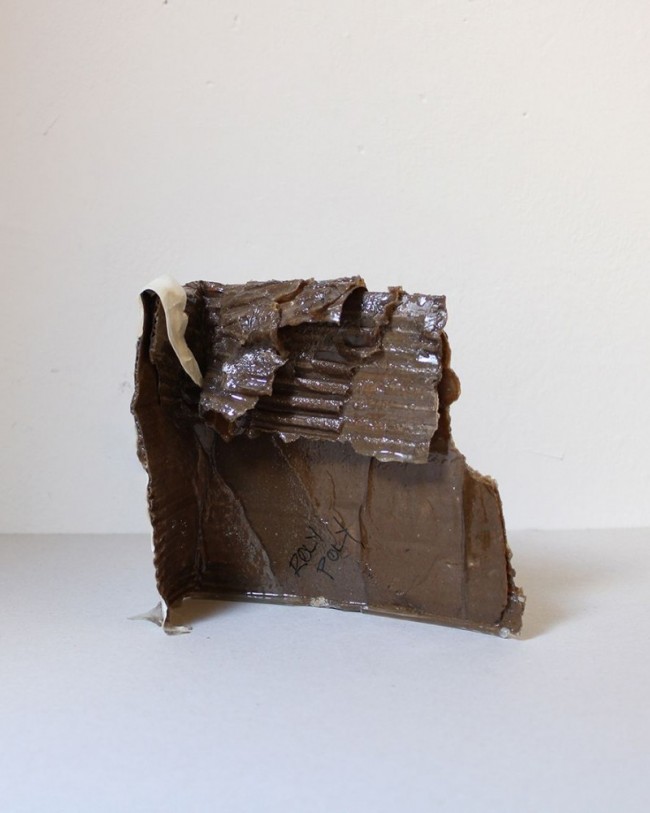

Compare that to the work you do with Friedman Benda gallery, for example, which consists of limited-edition objects available only to a select few.

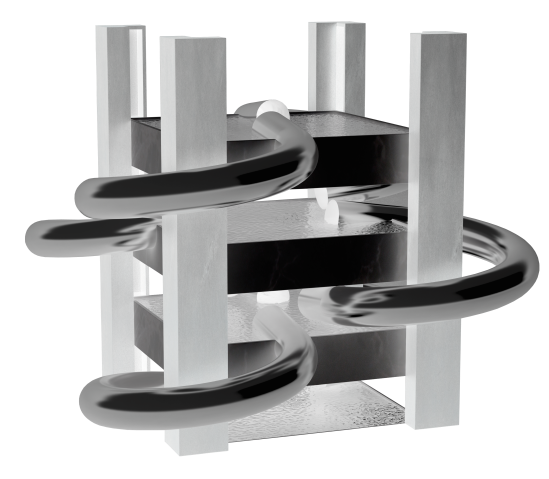

Right, the Hermès watch is very different from the Obelisk (a marble and glass lamp, available as an edition of eight) because most people will never see the Obelisk face-to-face or stand next to it. Even if they see it in magazines or on the website, they can’t touch it. For me, at least, it’s important to operate across scales in that sense, too: from mass-produced to super-limited. My process is the same no matter the project — it’s still my work, and each project is unique — but the parameters are different. If Knoll decides to make an object out of cast aluminum, then for me, the rules of cast aluminum will determine the object’s shape and expression. With Friedman Benda, the parameters are less limiting with regard to the material an object will be made of, but the fact that the object is limited in its availability and scope of reach, that’s also a parameter I use in my work.

So, without strict parameters, what materials do you gravitate to most?

Glass and crystal. I’ve been exploring those materials for years and they have yet to become boring. I’ve been throwing pottery since I was 12 years old and it’s still a very special idea to me — a curve revolving to create an object. Blown glass — all those forms — are coming in molds that are rotational in nature. But, really, put me in front of some other material and I’ll start falling in love with it too.

-

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

-

Ini Archibong poses with his brothers Archie Archibong (center) and Koko Archibong (right) on the stairs of the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

-

Ini Archibong photographed at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

We talked about having a global practice, but are there professional and creative reasons you stay in Switzerland?

I do like the concentration of craft in such a small area and the quality level makes it a strategically advantageous place for me to make special objects. I also have a longstanding interest in the watch industry, so it makes sense to maintain my access to watchmaking here. On the personal side, my daughter was born in a beautiful, clean, safe, country. Why would I leave that? That being said, I’m not necessarily selling to a Swiss market. Actually, yesterday was the first time I saw any of my products for sale in L.A.!

You sound surprised.

Honestly, it was strange. Growing up here, L.A. was a place where people with money were buying antiques. It’s catching up now, but when I decided to become a designer, I felt a lack of reference. I was going to New York, seeing cutting-edge design, and I was like, why can’t I find any of this stuff in L.A.? On the other hand, my work is heavily influenced by L.A. and Southern Californian art. I think you can see it just from the colors I use: the colors in my glass, the combinations, the psychedelia, the ’60s surfer Southern California art, the Montana spray (paint) cans, the colors you’d see in Candy Paint cars. All of that is going on in my work. Starting out, I devoured everything I could about design and found a world I could fit into.

Ini Archibong poses with Charles Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier)’s chez soi...., 1960 at the Swiss ambassador's residence in Washington D.C., February 25, 2020. © Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP

Do you remember anything particularly inspiring in that world?

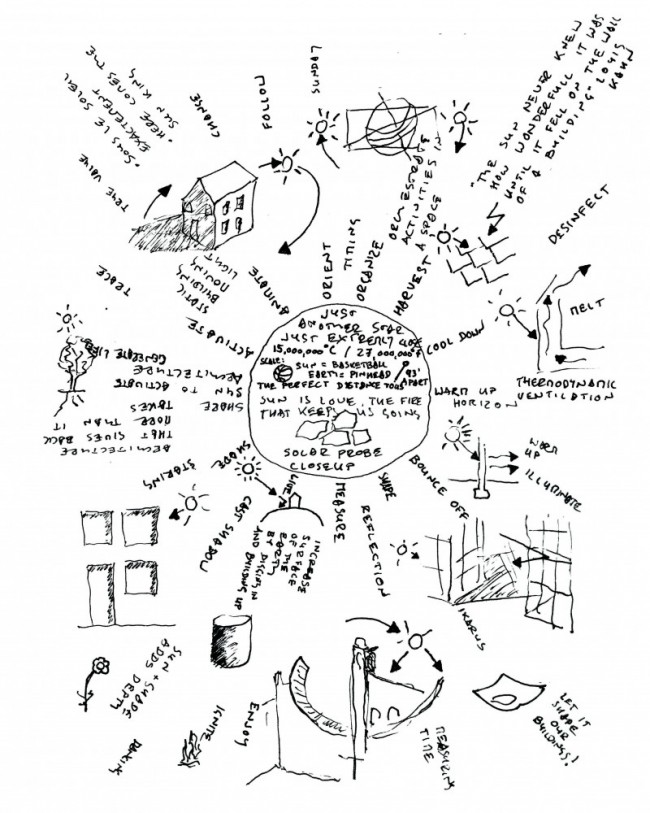

Early on, I remember seeing Marc Newson’s work — and just his career — and deep down thinking I had the potential to be a multidisciplinary designer who works across all scales. Working for big brands, working for luxury brands, working for non-luxury brands, working with galleries, doing big and small things, spaceships, boats, airplanes. The sky’s the limit, literally. Now (after performing as part of the Dallas Museum of Art exhibition), I can add performance artist to the list. I don’t think Marc Newson’s got that. (Laughs.) But even though I have favorites and people I love, another artist is basically the last thing I’m ever referencing now. I rarely look at design for inspiration. I dig into spirituality and try to deepen the lens I have of the universe around me and I try to get out of the way. I keep a sketchbook and imagine the brain like a desktop: I think of something, open a folder, put it inside, and when I’m home in ten days, as soon as I sit down, it’s the first idea coming back out.

Because you work with spiritual and poetic references, is it hard to communicate your ideas when collaborating with someone?

If you develop a good metaphor, everybody gets it. Direct and simple. I go to my glassblower and tell him, “these lamps need to feel like all the colors of a sunset rolled up into a single drop in the sky and landing at your feet in front of you.” And he says, “Okay, let’s make it.” (Laughs.) An object should communicate an idea to the people coming in contact with it. It’s a three-dimensional standing piece of poetry.

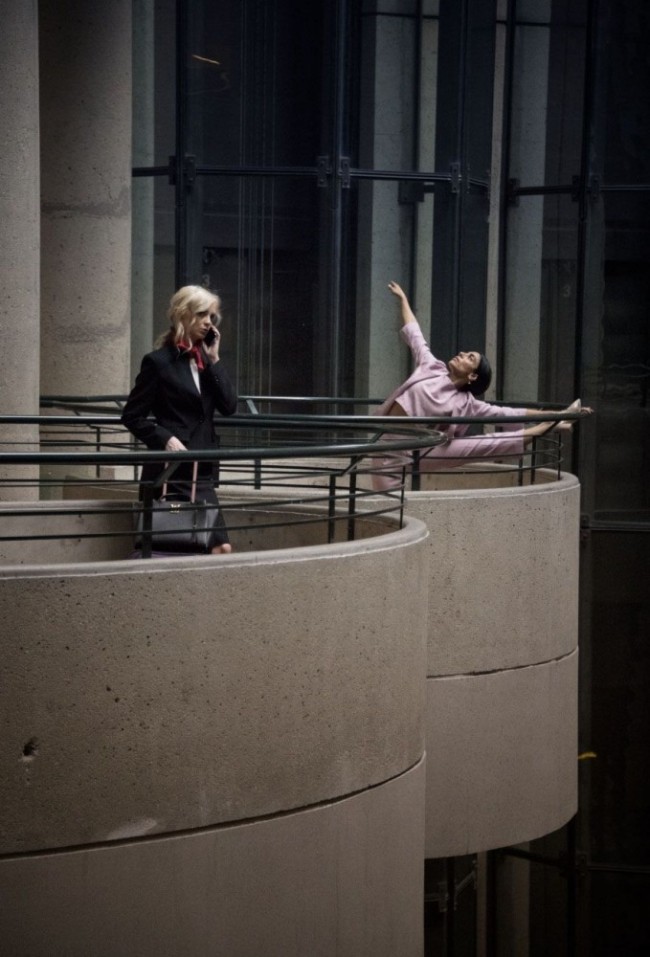

Clip from Ini Archibong, TheOracle (2019)

Featuring Archie Archibong, Ini Archibong, Nana Kwabena, and Nana Yaa.

Choreography by Nana Yaa.

Video by Eric Coleman.

Sound design by Archie Archibong Special thanks to Richard Morris (production), Hideki Yoshimoto (engineering), Edward Slater (engineering), and Matteo Gonet (glass-blowing).

Performance recorded on November 7, 2019 at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Interview by Katya Tylevich.

Photos by Felix Burrichter

Ini Archibong's installation TheOracle is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art as part of the exhibition Speechless until March 22, 2020.