A Holistic Winery at the Foot of the Andes in Chile

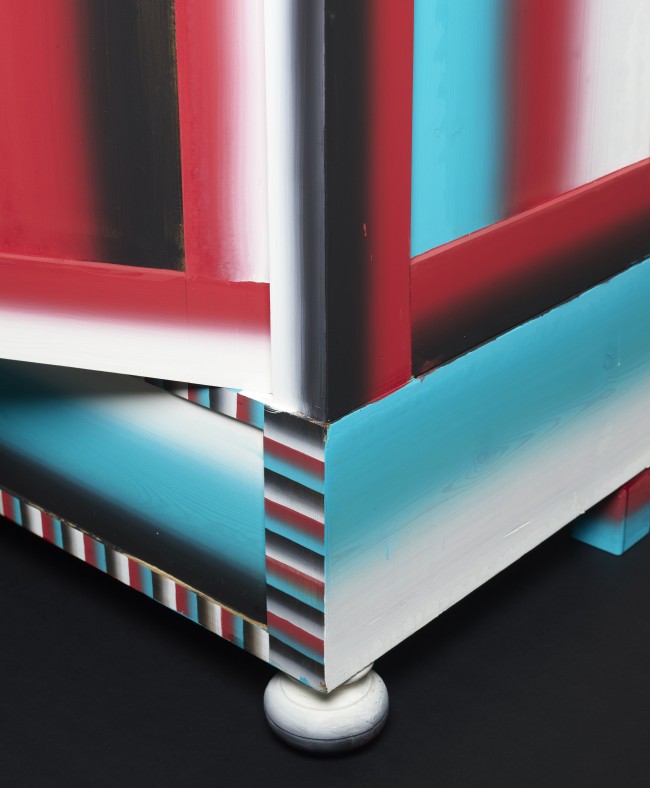

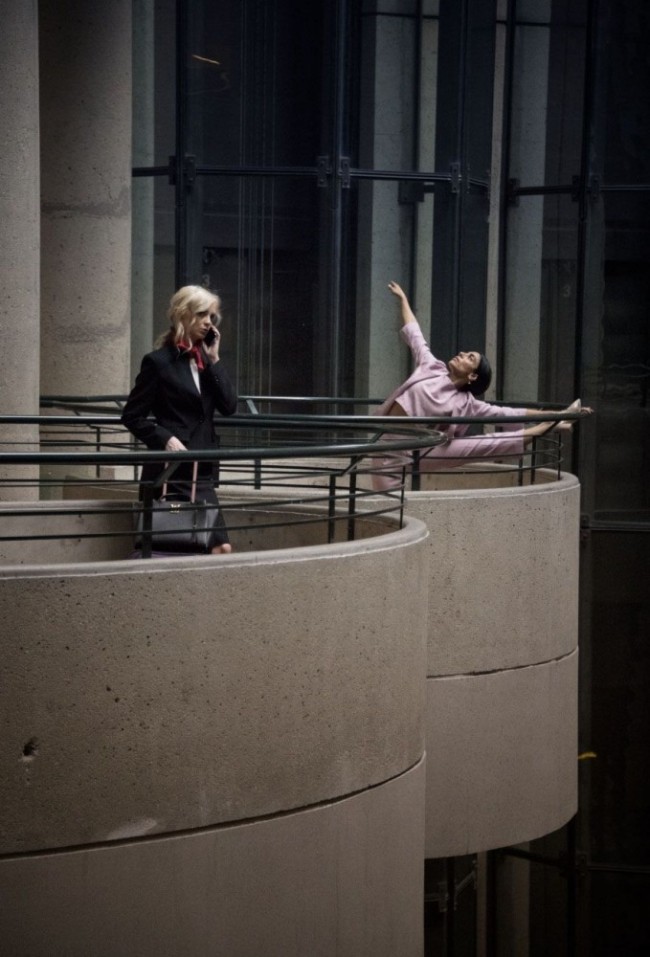

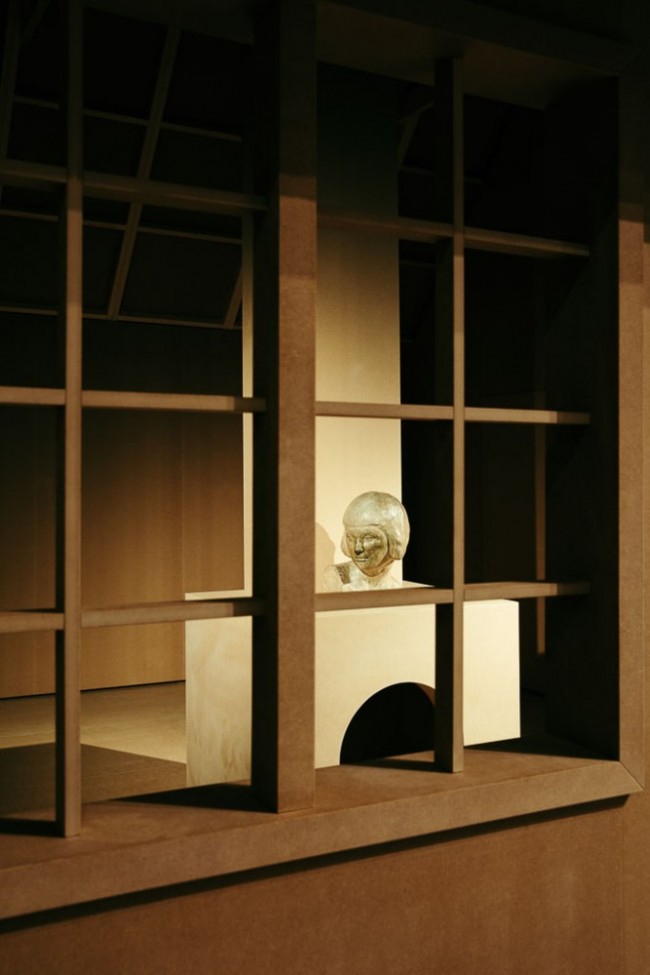

At first glance, Viña Vik, the avant-garde retreat and wine-spa owned by Alexander Vik and his wife Carrie, suggests a cult compound as imagined by Frank Gehry. Located among the hills of the Millahue Valley in Chile, about two hours’ drive from Santiago, the imposing hotel building is crowned by a gleaming bronzed-titanium roof that brings to mind an alien landing pad. It’s a fittingly exalted venue for the Viks. Their boutique luxury properties in José Ignacio, Uruguay have earned them a sect-like following for their artful embodying of the beach town’s pricey but diablo-may-care allure. As the newest addition to their portfolio, Viña Vik, which stems from Alexander Vik’s decision a decade ago to join the pantheon of wine greats, doesn’t disappoint. Perched on a hilltop that offers 360-degree views of 11,000 square feet of densely planted vineyards below, the blissfully remote hotel was designed by the Viks themselves, with help from Uruguayan architect Marcelo Daglio, and is a feast for the eyes as well as the palate. As with the couple’s other properties, there is a premium placed on meaningful artistic collaborations, with each of the 22 rooms and suites (only 50 guests are allowed at a time) essentially being site-specific installations featuring work by leading Chilean and international artists, including Marcela Correa, Antonio Seguí, and James Turrell. The airy reception area is dominated by a muscular Anselm Kiefer triptych, and a serene bonsai garden fills the hotel’s courtyard.

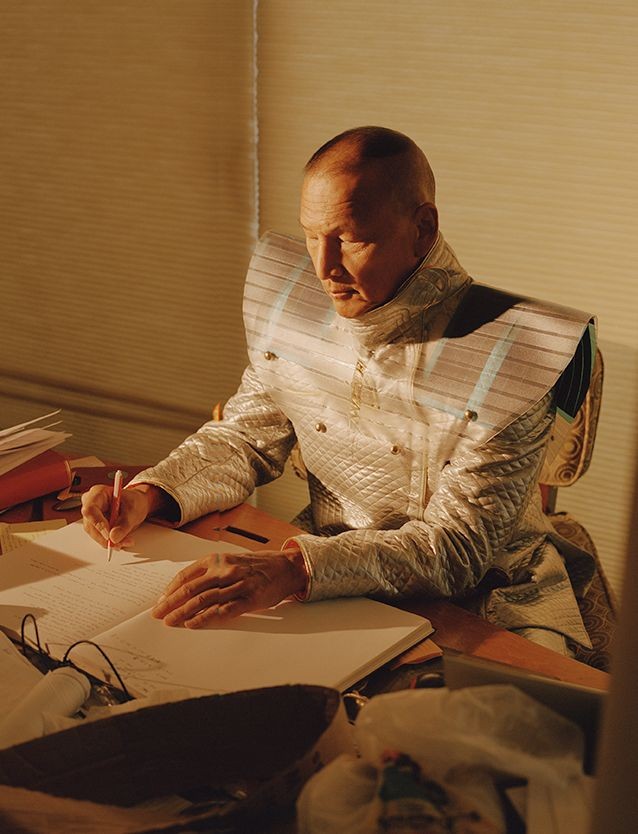

The wines produced at Viña Vik are a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon , Carménère, Syrah, Merlot and Cabernet Franc. They were developed with Patrick Valette, a noted Chilean vintner who was raised in France.

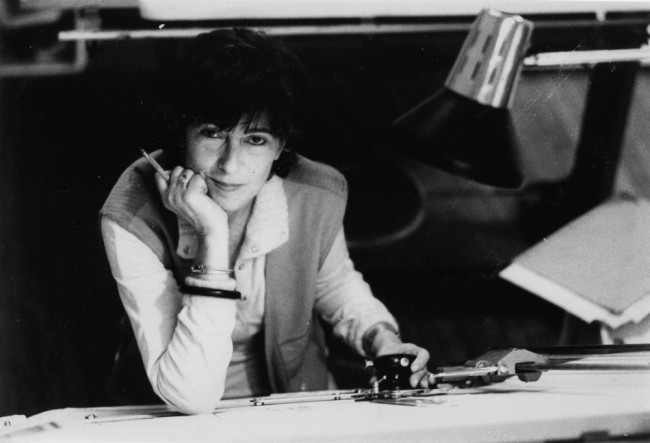

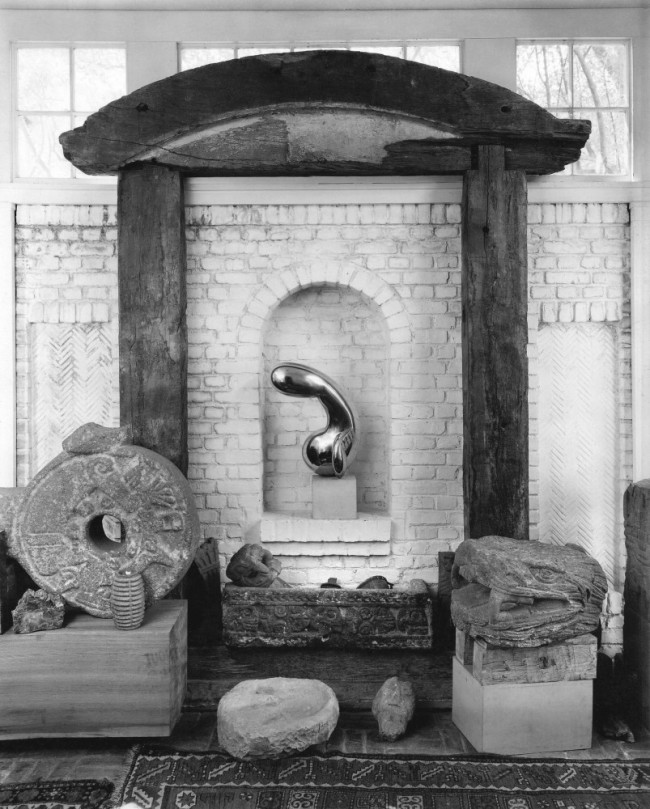

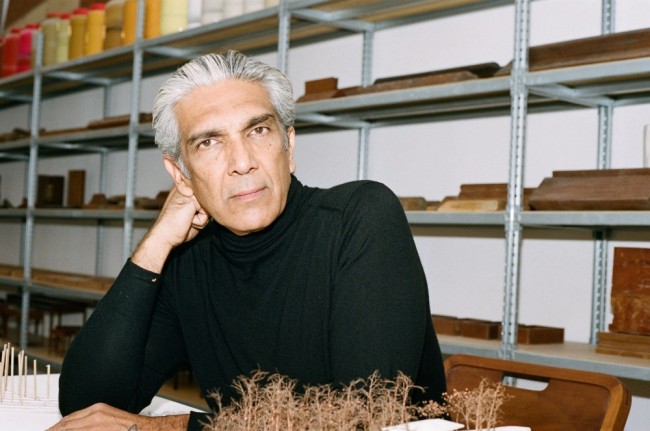

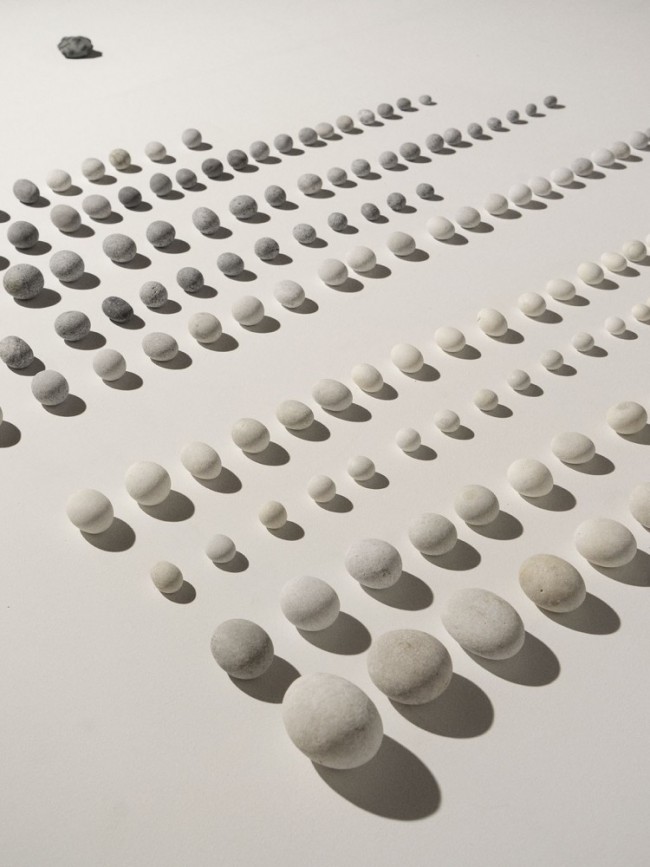

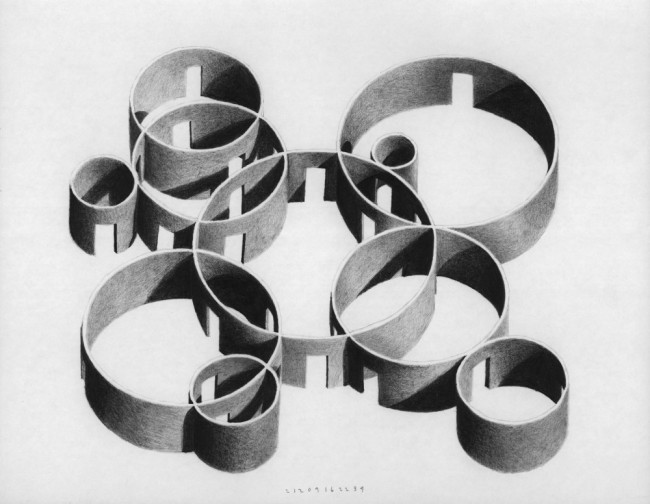

But it’s the state-of-the-art Vik Winery itself, 10 minutes’ walk from the hotel, which really rounds out the Chile wine-country experience and invites communion with nature. It’s here that the Viks have been producing since 2014, their eponymous premium blends — three well regarded vintages and counting. Framed by the Andes to the east and the Pacific to the west, and designed by Chilean architect Smiljan Radic, the spectacular production facility is partially buried in the middle of a field. Visitors approach the location, which was selected for the diversity of its terroir, on pathways made from locally sourced granite that traverse a gently rippling pool — the “water mirror” as it is known in Vik mythology — which reflects the indigenous shrubs and trees of the region (boldo, litre, quillay, peumo). “The water is part of a symbolic system for me, but it doesn’t end there,” explains Santiago-based Radic, who beat seven other architects in the competition to design the project. “The ancient rocks out front place the building in a different geological context, and the way the wind and the light play on the roof are also important. I never explain these things too much, but you feel these kinds of relations.”

The serenity of the exterior belies the chaos that takes place underground during harvest season - a duality that particularly appealed to Radic, who had never worked on a winery before the Vik commission.

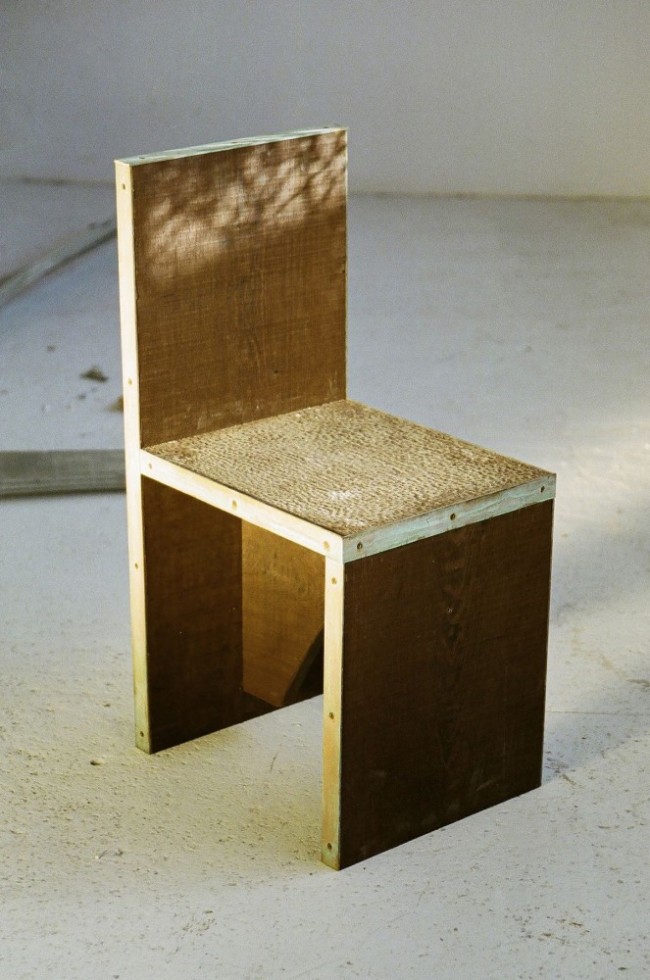

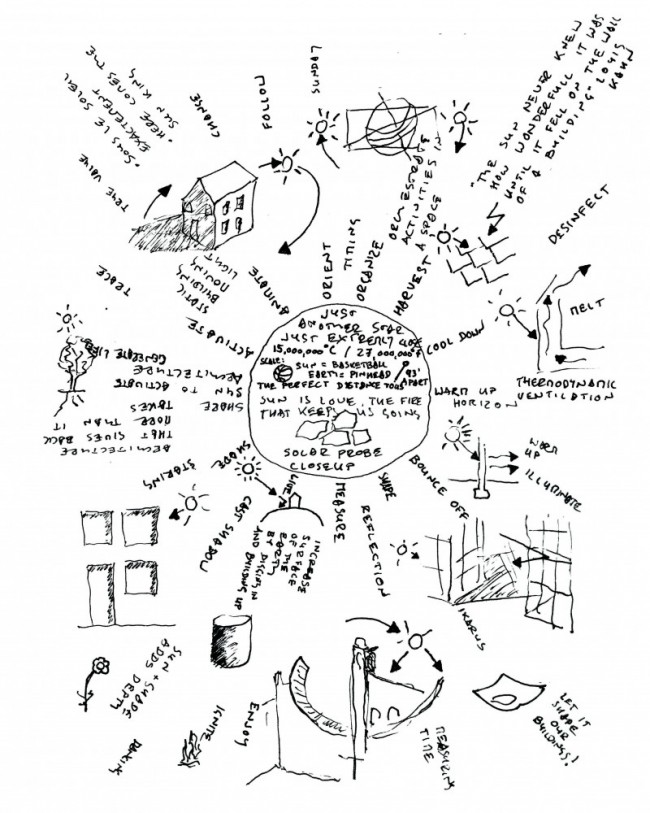

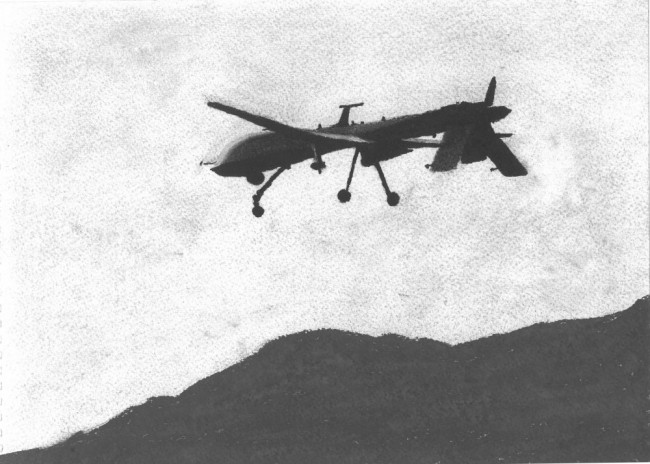

Beyond their symbolic connections to the immediate region and the Cordillera in the distance, Radic’s choices are part of a holistic commitment to minimize the need for energy use by maximizing natural resources to heat, cool, ventilate, and irrigate the 280-meter-long complex. The water mirror isn’t just mesmerizingly beautiful, it also moderates the temperature of the underground space where the barrels are kept; the special PTFE double membrane of the winery’s roof allows the light to sneak through but keeps the heat out. “It was important for the property to be visually stunning but to also be technologically creative and highly sustainable,” explains Alexander Vik. “The vision was to create a beautifully integrated winery that utilizes the earth and its capabilities to continue to help make great wine, while sitting elegantly among the vines with only the roofline visible.”

It’s an opinion shared by Radic. “So much of what we do as architects involves inflicting damage. The idea here was to create the least amount of damage and to contribute to the actual landscape as much as we possibly can. I want to create beautiful details that feel like they have always been here, but that at the same time are practical, useful, common sense. I don’t just want it to appear ecological — it has to be more than decoration in the end.”

Text by Horacio Silva.

Photography by Adrian Gaut.