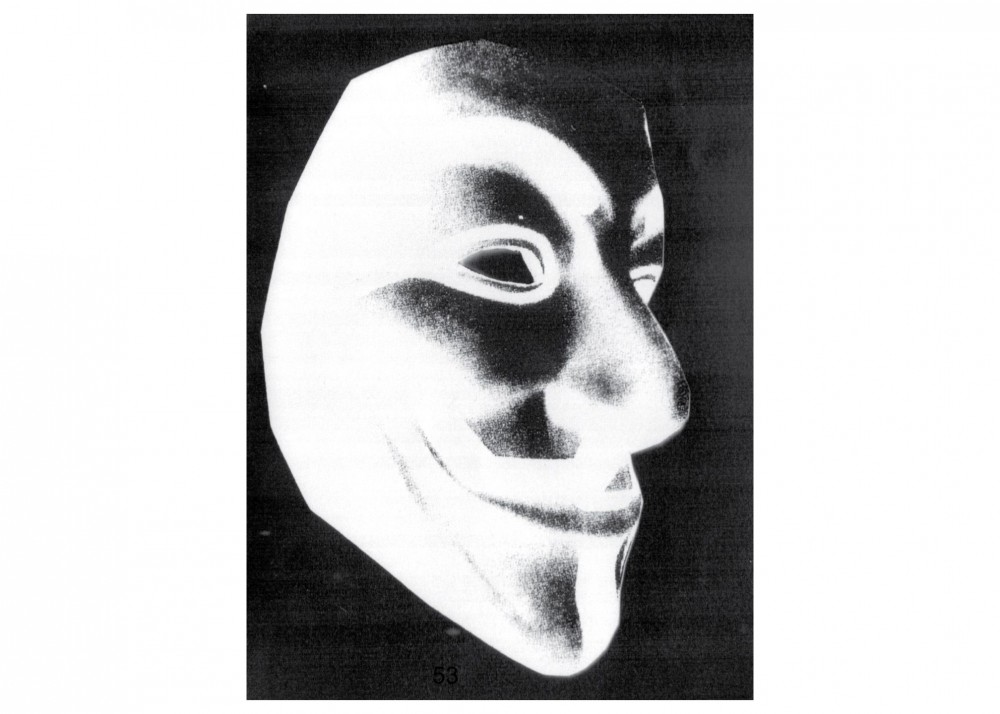

MASK UP: How The Guy Fawkes Mask Became One Of The Most Iconic Design Objects In Recent History

In V For Vendetta, the 2005 adaptation of an 80s graphic novel, the titular “V” wears what has become one of the most recognizable, iconic visual signifiers of the last two decades: a bone-white vaudeville mask made to resemble an unheimlich, funhouse-mirror version of the face of Guy Fawkes, the 17th-century Papal fanatic and would-be terrorist. The film is set in London c. 2020, under the rule of a total and unmerciful police state, with V as an anonymous and furious anti-fascist bent on systematically destroying his oppressors. He meets Evey, a doe-eyed TV reporter played with an occasionally baffling English accent by a young Natalie Portman, after rescuing her from a rape attempt by two policemen; he absconds with her to his underground lair, plays her some contraband pop music on his jukebox, serves her breakfast, and afterwards radicalizes her by playing mind games, imprisoning her, shaving her perfectly-shaped head, and teaching her that people should not fear their governments. “Governments,” he assures her, “should be afraid of their people.”

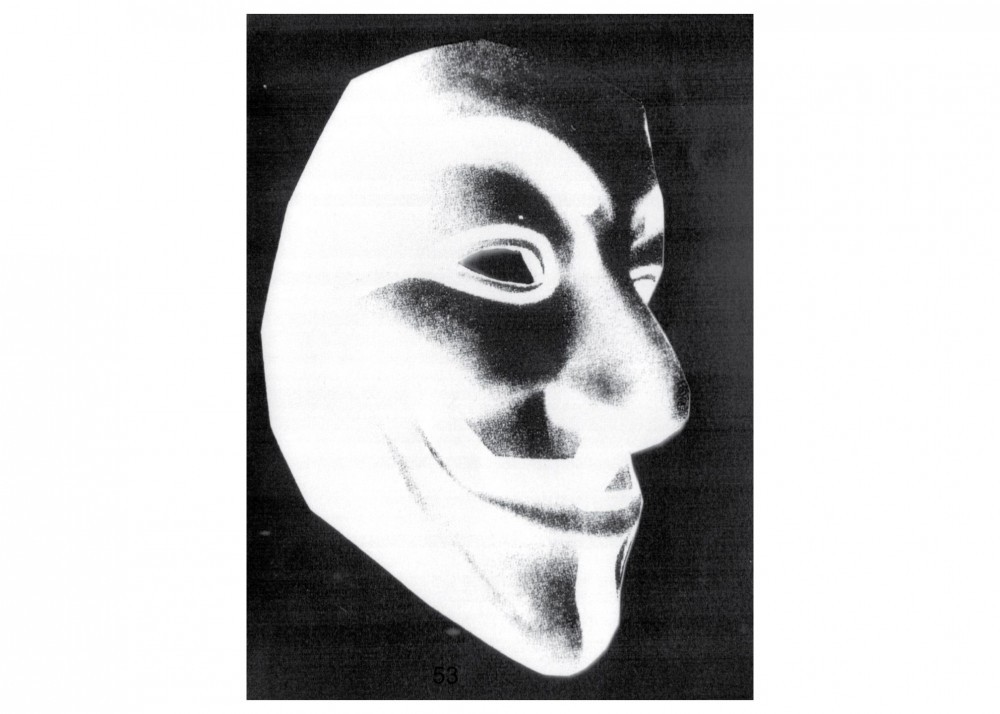

While Guy Fawkes masks have a long tradition, today’s ubiquitous design object comes from the stylized face illustrator David Lloyd created for the 1980s graphic novel V for Vendetta.

Women, it ought to be noted, should be at least a little afraid of men who kidnap them and subject them to such indignities. Still, Evey understands V’s point, even if she is not particularly thrilled with how he makes it: by the last scene, as a mammoth crowd of people wearing copies of his mask descends on the Houses of Parliament, she has accepted that he stands for “all of us.” More simplistic and less brutal than its source material, the movie version of V For Vendetta is about anonymous, lone-wolf malcontents banding together to dismantle a corrupt right-wing state. (It is also a film about a mysterious, kung-fu-literate man rescuing and then kidnapping a luminous Natalie Portman, which may help to explain its enduring popularity in certain corners of the web.) When it first premiered, Warner Brothers handed out replica copies of V’s mask, a genius marketing idea that quickly snowballed into a phenomenon as protest groups began to use it in exactly the way V and his disciples did — for personal protection, for intimidation, for guaranteed anonymity, and as a marker of subversive, anti-government beliefs. It was, for some time, the best-selling mask on earth, and Time Warner receives a cut of every sale.

Demonstrators wearing Guy Fawkes masks during a protest at Urban Council Centenary Garden in Hong Kong, November 2019.

In Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s original graphic novel, V is interested in the theatricality of violence as well as what he perceives as its ability to liberate. The curious flamboyance of his chosen uniform, not so much historical re-enactment as hysterical Fawkes drag, is meant to underscore the drama of his very stylized, very public acts of personal and political vengeance. “Isn’t it strange how life turns into melodrama?”, he asks Evey, when she wonders why he looks the way he does. “(Theatricality) is everything. The perfect entrance. The grand illusion … I’m going to remind them about melodrama ... You see, Evey, all the world’s a stage, and everything else is vaudeville.” The costume’s wig, a sleek black bob with blunt-edged bangs somehow more reminiscent of Cleopatra than a 17th-century soldier, is feminized in such a way that V — despite the mask’s goatee and moustache — does not appear to be strictly male or female. The mask’s cheekbones, squeezed high by its eerie smile, are rouged like dolls’ cheeks. It does not seem to suggest an everyman so much as an everyman-woman-other, making it an ideal symbol for a group with a fluid, unknowable identity. It has some of the spooky majesty of the masks worn in Japanese Noh theater, but a broader, poppier public profile — as recognizable a piece of branded design as a yellow smiley face.

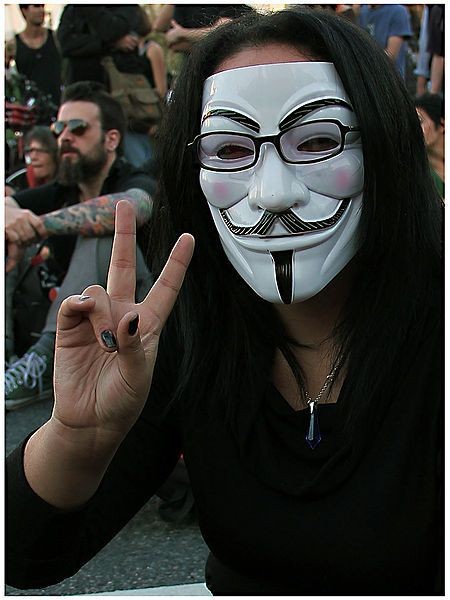

Venezuelan protester wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, May 2014.

Lloyd, the artist who originally drew V’s mask, attended the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011 in order to see his design making the leap into real life. “The Guy Fawkes mask has become a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny — and I’m happy with people using it,” he told the BBC. “My feeling is the Anonymous group needed an all-purpose image to hide their identity and also symbolize that they stand for individualism.” Hacker-activists whose targets have included Scientology, The Westboro Baptist Church, and several international governments, Anonymous have created an interesting feedback loop with their use of V’s mask — the graphic novel, which depicts a heavily-surveilled society kept in check by an ongoing demonization of the other, has long been seen to be prescient, making the appropriation of its visual markers by a non-fictional group a case of art predicting real life and then going on to shape it. It is an appropriately murky, shifting kind of cultural significance for a design object that represents both individual and movement, antifascism and violence, history and a resistance to repeating its mistakes.

A YouTuber shows off his Guy Fawkes mask, 2018.

Text by Philippa Snow.

Taken from PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.