ESTATE REALNESS: How the Stars of Selling Sunset Mirror The Luxury Properties They Sell

In the same way pets and owners are eventually said to come to resemble each other, it is possible to argue that at least half of the bone-thin, coiffed, Amazonian agents on the Netflix series Selling Sunset are reflections of the real estate they sell: sexy, expensive, ultramodern, very L.A. They are not so much “bad taste” or “tasteless” as they are devoid of taste entirely, a blank canvas zhuzhed with pops of whatever color or signifier has a proven record of appealing to interested buyers that calendar year. Maya, a wry, slender Israeli with a charmingly inept grasp of idiomatic English, is the sane one, more inclined to repair bridges than to burn them, and as such is the one most likely to be seen in a hard-hat going over structural plans and regulations. Mary, temperate and sweet and close to forty, has a very young fiancé and a clever aesthetician, making her the equivalent of a classic retro build that has been modernized in such a way that the property still retains original features. Christine is the brilliant, all-time-greatest bitch whose workplace manner is akin to that of a particularly scathing drag queen doing a routine as Joan Crawford. She calls herself a “gothic Barbie,” but is really more like one of the houses she specializes in in the Hollywood Hills: flashy, unapologetically over-the-top, and exorbitant to maintain. Heather, a former Playboy bunny, has never mirrored a listing more than the property she adorned with bright pink butterfly-and-flower-covered street art near the end of season three. Chrishell, a gentle former soap star, is as warm and reasonable as the lower-priced, less ostentatious family homes she is assigned to in the Valley, her neat nose job and broad smile half-mom, half Miss Kentucky.

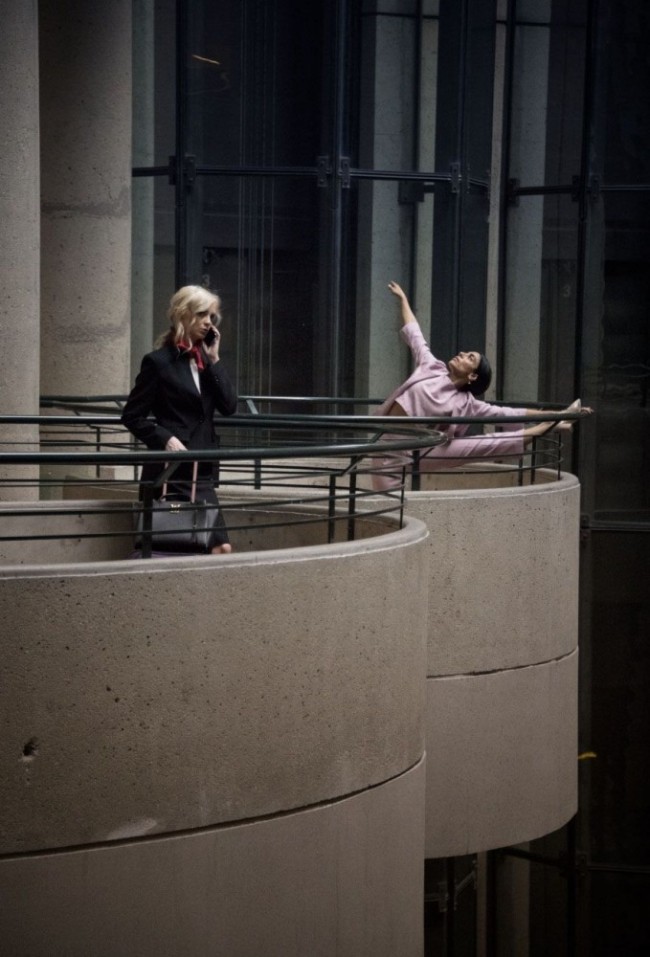

Davina (left) and Christine (right) touring a potential listing on Selling Sunset.

In addition to its tiny twin founders Brett and Jason, the Oppenheim brokerage firm is made up of two more members: Amanza, a goofy-gorgeous newcomer who is to date the only non-white woman in the office, and whose personal style is more Lisa Bonet than L.A. Barbie, and Davina, a bad-tempered, brown-haired demon in middling business-casual who lives to bitch and stir up chaos. Both are still finding their grooves with real estate, Amanza having only been officially qualified as an agent since 2019, and Davina having been patently useless for the show’s entire run. Whether or not they will end up conforming to the style preferred by the five office blondes — what Christine calls a “CE-Ho” look, achieved with a label-led designer “whoredrobe” — will remain unclear until Netflix releases a new season. What is apparent is the synchronicity between this style and the interiors on the show, which compliment it by offering up their featureless expanses of white space to be adorned by these similarly hyper-feminine, extremely argumentative girlbosses, making them resemble dolls being played with in a series of ever-more cavernous dollhouses. An obscenely costly megamansion — vacant and seemingly soulless, pale as cocaine — only amplifies the conflict that expresses itself in it, like the basic chalk-drawn sets in Lars von Trier’s cruel, metaphoric movie Dogville. “(It is) pure artifice… not a breath of air or natural light passes across the set,” The New Yorker’s David Denby wrote once about the visual minimalism of that film — which, much like Selling Sunset, is essentially an exploration of typical American values. “We’re in the dead zone of schematic abstraction and didactic moral fable.” There is a didactic moral fable at the heart of Selling Sunset, too — a conflict between good and evil, amplified by editing and by the natural human impulse to take sides. Neutrality, in matters of the heart if not in matters of interior décor, is difficult to maintain.

View of Hollywood Hills, featuring a $40 million home (center) sold by the Oppenheim Group.

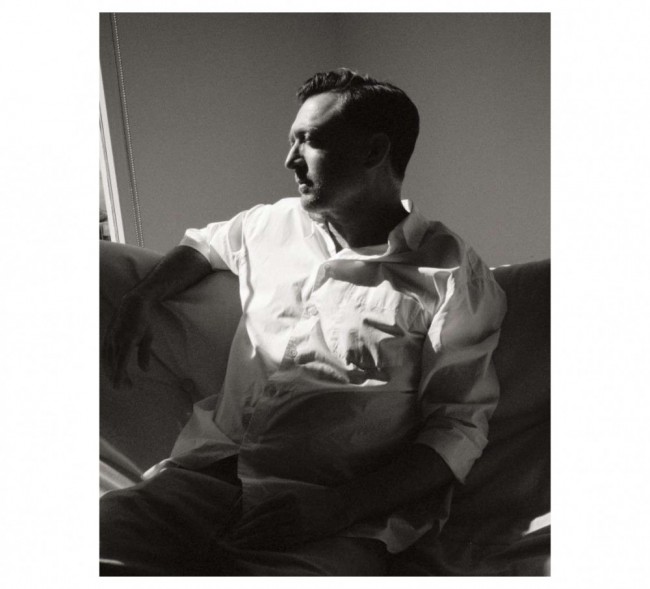

If the long-suffering Mary is the office teacher’s pet, and Chrishelle is the wide-eyed babe, the group’s unmerciful and undisputed ruler is Christine, whose physical architecture and deliberately selected slut-couture both appear engineered not only for reality stardom, but for setting off the kind of home that might be purchased by a Los Angeles playboy. The Christine of season one — who had not yet seen herself moulded into Selling Sunset’s high-camp Disney villain by a perfect combination of her own blustering rudeness, and a sly, experienced editorial hand — was hot and mean, but in an ordinary way. The new Christine, who saw that Christine on the show and decided that she seemed too regular in her meanness and her hotness, too, has exploded both attributes out to their limits. (“Christine’s…family values are what set her apart from others in the industry,” the Oppenheim Group’s website boasts, presumably describing an entirely different woman named Christine.) Her aesthetic and emotional refurbishments have, there is no doubt, added value, making her the MVP of Selling Sunset. “In the world of Selling Sunset, Christine is a limit case,” critic Naomi Fry suggests, “and her over-the-top power-ditz act appears, at times, nearly parodic.” She embodies a peculiarly Los Angelean promise — that enough cash and enough flash, to say nothing of extensive renovation, can make any self-confessed uncool high schooler into hot, unobtainable property, impossible to own unless you are a multimillionaire.

Self-anointed “gothic Barbie” Christine Quinn, the star of Netflix reality show Selling Sunset.

Her aptitude for accessorizing her real estate is never more evident than in a season two episode, in which she tours an eighty-million-dollar mansion in a lilac miniskirt, a baby-pink marabou-trimmed bustier, vertiginous high-heeled shoes, and a Chanel-style boucle jacket the same color as blancmange. “I knew that we were shooting in this gorgeous $80 million house and it happened to be very feminine and it had a lot of pink and it had a lot of purple,” she told Page Six. “So I wanted to play up the purple Balenciaga, the (pink) Chanel python bag. I really wanted to go along with my environment, and I thought it looked so great in the scene because I matched the house that I loved.” To call the house “feminine” is, at best, a stretch — it has a few candy-bright pillows, a smattering of pretty, violaceous chairs, and one large photograph of Marilyn Monroe, but otherwise it is as blank as most of the Oppenheim Group’s usual fare. That Christine sees it as feminal in its décor is indicative of how far individuality and character are unusual in her field. “There is something very sexy and appealing about living in the Hollywood Hills,” Maya says in the first episode. “Like, you’re talking about the history of Hollywood.” Too much history, though, appears to work against a sale. Houses by Richard Neutra and Harry Gesner, quirkily mid-century on the exterior, have been washed-out and modernized on the inside in order to suit the brokerage’s male clients, who tend to be interested in wowing women or business associates rather than revelling in the history of design. As with the houses, so with the Oppenheim agents: Mary and Chrishelle, who were both born sometime around 1980, do not look exactly vintage. Christine, who is 32, looks ageless, less in the sense of appearing very young than in the sense of looking as if she might plausibly be literally any age between 18 and 38. Investing in a mansion in Beverly Hills and maintaining the face and body of a person tasked with selling them are not so different. Both take hard work, inherited wealth, or both; both are an ongoing investment rather than a one-off splurge, requiring tweaks and routine upgrades, the result ideally fresh and universally appealing. “I’m not fake,” Christine insists. “I mean my tits are fake, but that’s it — I’m not fake.” She is not wrong: she has never pretended to be anything other than a terribly exclusive luxury development, rebuilt from the foundations up.

The Oppenheim Group's open-concept offices in a 125-year-old building on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Sunset Plaza Dr.

Text by Philippa Snow.

Stills from Selling Sunset (Netflix, 2019–20).