VENICE 2019: The Rise of the Urban Biennale

The Ukrainian Pavilion: An-225 Mriya cargo-plane flying over Venice. Photo Vasiliy Koba, Courtesy Antonov Company.

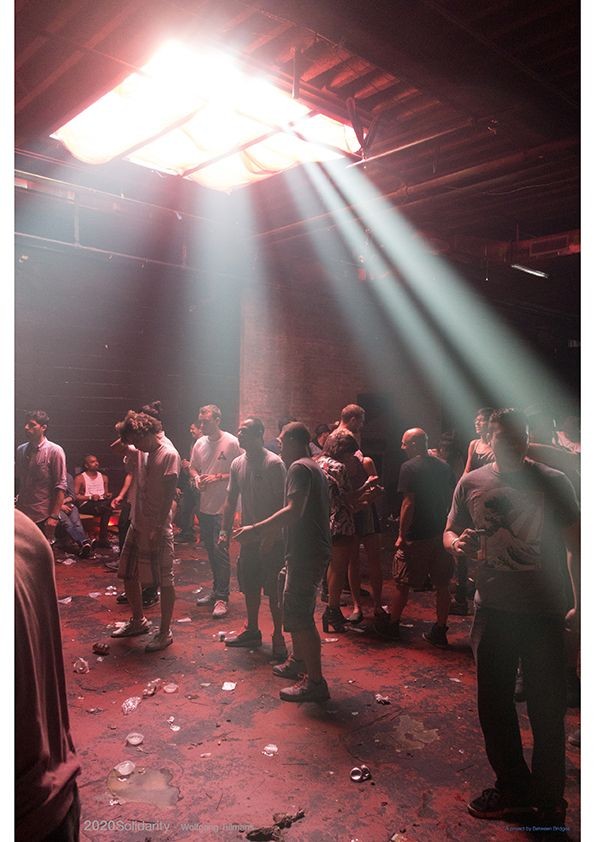

In 2019, about 300 biennales will open globally, each presenting its own view of the world’s most important art. That’s more biennales than there are countries. This proliferation of the international art exhibition is challenging the original century-old format of the biennale. In Venice, where its 58th Biennale May You Live in Interesting Times opened last May, new ideas and experiments take place away from its central Giardini and Arsenale sites — sprawling across the city’s many palazzos, piazzas, streets, and stoops. Even the canvas of the sky above has been painted; as part of the Ukrainian Pavilion, a 225 Mriya cargo plane flew over Venice. This urbanization of the biennale, moving art outside traditional venues and into the city itself, offers relief to the ticketed and over-crowded exhibition spaces. But what is the point of a biennale when the most innovative (and lauded) works are exhibited place off-site? And if a biennale so fully colonizes a city, what happens to that city when these exhibition sites inevitably close down at the end of the biennale's run?

Venice under water. © Luigi Constantini

Venice is an architectural Frankenstein’s monster. Sunken islands and overflown waterways are sewn together by hundreds structurally unsound bridges. To get to the Biennale, one has to navigate a complex web of barely accessible dead-end streets and bewildered tourists, leaving the city feeling like a Gothic amusement park where long lines overshadow short rides. But to Venice, the spectacle of waiting is nothing new. When in 1348 the Black Plague devastated its population, the city introduced a quarantine, enforcing visitors to wait 40 days upon entry. Much as contemporary art has never quite become the epitome of accessibility, this year’s Biennale struggles to deliver the minimal infrastructure to accommodate visitors — water, food, shelter, and sanitation — bringing into question who the Biennale actually is for. While curator Ralph Rugoff describes the exhibition as an investigation of "cultural boundaries" that "embraces art's social function," its quarantine-like door policy and roster of blue-chip gallery and established museum-artists like Nicole Eisenman and Jimmie Durham renders the Biennale more art fair than celebration of fair art.

The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk traces the origin of the biennale to London’s Great Exhibition in 1851. In In the World of Interior Capital, Sloterdijk distinguishes this Great Exhibition from other international exhibition by highlighting its objective to establish economic leadership, rather than to promote cultural exchange. During the late 19th century, when the city of Venice fell into decline, its council took notice of this British precedent. However, rather than building its own iconic Crystal Palace, Venice assigned the architecture of its two city parks, the Giardini and later the Arsenale, to the Biennale — transforming these former wastelands into the cultural destinations they are today. Art and gentrification go way back.

Souvenir of the Great Exhibition, The Transept from the Grand Entrance, 1851. Image courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Today, a growing number of cities seek biennales — and more and more countries seek representation in Venice. However, the century-old architectural configuration of the Biennale struggles to keep up with this international proliferation, as its main sites are historically committed to Western European pavilions. Venice, rather than building out its Biennale architecture, forces newcomers like Côte d’Ivoire to expand into the city, often making these new entrants submit to Venice’s commercial real estate market, and cough up large sums of money in the process. This expansion into the city is further perpetuated by a series of international galleries and foundations entering the fray, such as Victoria Miro, Fondazione Prada, or the V-A-C Foundation’s Venetian headquarters. Setting up camp for art season, they are not only blurring the distinction between what is institutional or commercial art, but also straining Venice’s real-estate economy even more.

As the so-called “Bilbao Effect” illustrates, cultural investment in architecture can uplift the economy of a city. However, the Biennale Effect operates in temporary real estate bubbles where short-term capital wins out over local and long-term investment. In the case of Venice, it also displaces a population of just 50,000 people even more. Art may not be able to solve real estate problems any more than biennales can fix a city, but it is important for culture to challenge the conditions it operates in. When the Havana Biennale launched in 1984, it did so by rejecting the traditional format of state-pavilions to favor thematically-linked exhibitions and more experimental artists. More recently, in 2016, the São Paulo Biennale challenged the dominant modus operandi of international curators parachuting into new regions bringing along with them an established roster of artists. Instead, it manifested a de-colonial mission that highlighted local and emerging artists. But as biennales experiment, not all do so successfully: the most recent Kochi-Muziris Biennale, in India, is stuck in a legal battle to pay out to its local workers and the 2018 Gwangju Biennale, in its attempt to represent the entirety of Asia, generated controversy when it exhibited work by North Korean artists.

Choe Yu-song, On the Way Home. Image courtesy Gwangju Biennale.

Public failures like these shed a much-needed light on the complexity of increasingly global art fairs and exhibitions. So, when this year’s Venice Biennale failed to apply any of its 14-million-dollar budget to explore “cultural boundaries” and “art’s social function” locally, it became just another exhibition presenting ideas it does not embody. Simultaneously, its conventional set-up enabled a perpetuation of a white, Western, and market-driven hegemony, while draining the city’s sparse resources. And so, the 2019 Venice Biennale not only fails curatorially, it fails to do so interestingly. This may come as no surprise for a biennale that applauds itself for its gender parity in 2019 (which should be a prerequisite rather than triumph) and lays claim to diversity and sustainability, all the while forcing new, less-established entrants out of the exhibition’s center and into the city, propping up massive real estate bubbles in the process.

What happened to the idea of the Biennale in service of cultural exchange across the city and globe, not just as a tool in service of raising property values to the benefit of the few? The most telling thing about the 58th Biennale may be its title, an English expression of a supposed "Chinese curse" for which no Chinese source has ever been found. After all, why May You Live In Interesting Times and not We?

Text by Vere van Gool for PIN–UP Online.