META MEMPHIS: The Little Known Story of Memphis’s Second Coming

-

Cover of the 1989 Meta Memphis Collection.

-

Cover of the 1991 Meta Memphis Collection.

History, as is widely known, ended quite some time ago. Though the time of death remains uncertain, the cause is clear: Postmodernism. Both an aesthetic style and a broader cultural philosophy, Postmodernism came to prominence in the late 1970s and reached its apex in the mid-80s, leaving in its wake a laundry list of casualties, chief among them the idea of linear progress. In 1984, Fredric Jameson, perhaps the canonical theorist of Postmodernism, described its effect as “the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense.”

Pier Paolo Calzolari, Pao bench (1989); Meta Memphis Collection from 1989. Image courtesy of Memphis Milano.

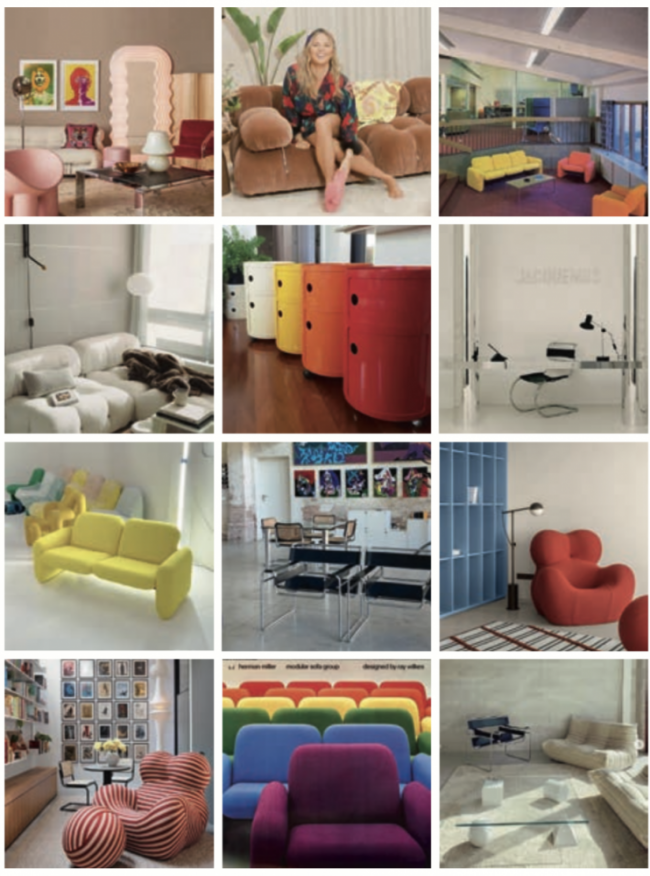

If, 40-some years ago, Postmodernism was the preserve of philosophers and academics studying architecture and art history, today it’s ubiquitous on social media. Instagram is, as Taylore Scabarelli noted in this very magazine, the epitome of the end of history, “a place where trends go to die, only to be reborn moments later.” From Y2K fashion to the pop-punk revival, the new hot thing is often just an old trend plucked from the past and framed as fresh. The feed, like time itself, is a flat circle: scroll through long enough and you’ll end up exactly where you began. The result is an eternal return of the same. Where design is concerned, that usually translates into Marcel Breuer Wassily chairs, Michel Ducarcy Togo sofas, and, of course, a touch or two of Memphis.

-

Bill Woodrow, Ellen I, 1991. Meta Memphis Collection II.

-

Bill Woodrow, Ellen II, 1991. Meta Memphis Collection II.

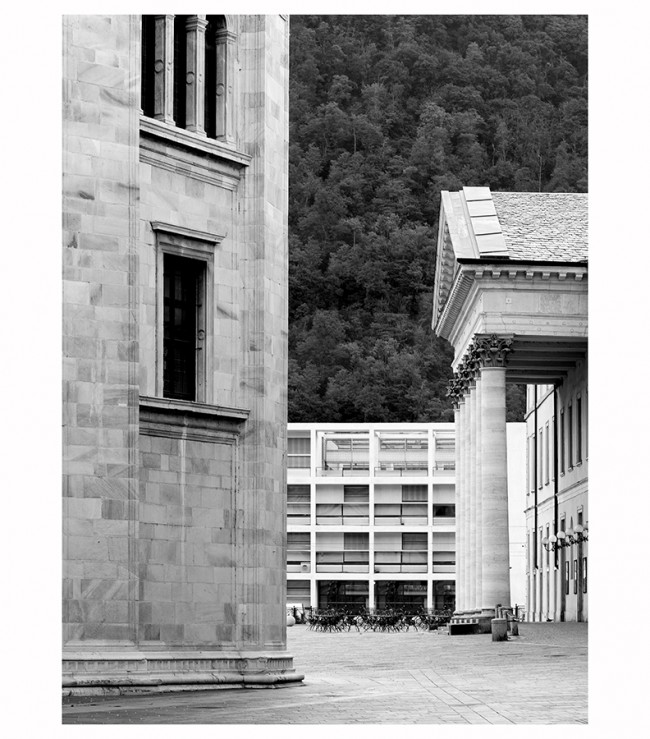

The origins of Memphis can be traced back to December 11, 1980, when Ettore Sottsass, then in his 60s, met with a group of younger architects and designers at home in his Milan apartment. By February 1981, Memphis Milano — whose members included Aldo Cibic, Martine Bedin, Michele De Lucchi, Nathalie Du Pasquier, George Sowden, Matteo Thun, and Marco Zanini — had been officially founded. Drawing simultaneously on ancient Egypt, modern America, and Bob Dylan, whose “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” played repeatedly through that fateful night, the group collapsed distinctions into pure surface, allowing a hodgepodge of references and eras to coexist and reimagining what furniture could be. Until Memphis Milano disbanded, in 1988, it stayed true to what was, in many ways, a radical vision. The use of outré pattern and color, of mundane materials like laminate, and the embrace of playful, over-the-top forms broke with convention, questioning the very basis of taste. Beneath the surface of the Memphis style, however, lurked a latent conservatism. Though the designs are aesthetically shocking, the typologies are familiar. A teapot by Peter Shire (who was associated with the group), for example, might overwhelm the eyes, but hold one in your hands and it’s quite clear what it’s for and how to use it.

Difference, as theorized by Kierkegaard, is predicated on a continuation with the past, because it requires recognition. To realize, for example, that a Memphis chair is different from an older chair, we first must be able to tell that both are chairs. In this sense, most of what we would generally think of as “new” is in fact just different. The true new, on the other hand, is something we cannot recognize, at least at the moment of its appearance: it is so substantively other that it evades our perception. Seen within the logic of the social-media feed, it becomes clear why the aesthetics of difference perfected by Memphis have stayed so prominent: it is just strange enough that it seems fresh and exciting, but familiar enough not to be confusing (the user doesn’t scroll right past).

Franz West, Privatlampe des Künstlers II (1989); Meta Memphis Collection 1989. Image courtesy of Memphis Milano.

After the Memphis Milano group disbanded, the company itself remained in existence under the guidance of Ernesto Gismondi, the founder of Artemide. In 1989, Gismondi launched a new project: Meta Memphis. Only two Meta Memphis collections were released, in 1989 and 1991. Both involved collaborations with artists rather than designers, among them leading figures in Arte Povera — Pier Paolo Calzolari, Sandro Chia, and Michelangelo Pistoletto — and conceptual art: Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Susana Solano, and Franz West.

Joseph Kosuth, Modus Operandi (1989). Meta Memphis Collection 1989.

Stylistically, Meta Memphis was a vast shift from Memphis Milano, austere and almost minimalist in contrast, favoring materials with more weight, both literally and metaphorically. The objects resist easy description, from Alighiero e Boetti’s illegible clock to Bill Woodrow’s tables balancing on plexiglass spheres. After all, could a conceptualist like Kosuth, who famously deconstructed the very meaning of a chair in his 1965 work One and Three Chairs, really be expected to make a standard chaise longue? Modus Operandi, his contribution to the first Meta Memphis collection, clearly demonstrates not.

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Tavolo a stella, 1989. Meta Memphis Collection I. Image courtesy of Memphis Milano.

Despite the aesthetic disparity with Memphis Milano, Meta Memphis still operated according to the same principles and impulses, seeking to question the very nature of industrial design. But it went beyond the limits of Memphis Milano, operating outside the conventions of not only form but also function. As the line between art and object increasingly blurred, Meta Memphis was able to create a truly new design, one that often verged on complete illegibility.

Sol LeWitt, Table (1991); Meta Memphis Collection II. Image courtesy of Memphis Milano.

In contrast to Memphis Milano’s ongoing popularity, the two Meta Memphis collections remain largely overlooked. “They certainly weren’t easy to sell or imagine in one’s home,” says Joseph Magliaro, founder of the experimental-design space Table of Contents, in Portland, Oregon, where he curated the first ever U.S. Meta Memphis show in 2015. This was true even at its outset. Speaking to The New York Times about the Meta Memphis debut in 1989, Zanini, one of the founding members of Memphis Milano, acidly declared, “Nobody, at least nobody I know, went to see it.”

Maurizio Mochetti, Un posto per Charlie table (1989). Meta Memphis Collection from 1989. Image courtesy of Memphis Milano.

Today, when Memphis-style design is everywhere, the full catalogue archive is easily findable online, and there is a growing cultural appreciation for unearthing vintage design, the lack of knowledge about Meta Memphis seems especially remarkable. This is in part due to scarcity, since many of the pieces were produced in limited editions of 25. But, according to Magliaro, it is also caused by the very nature of the new. Unrecognizable and uncategorizable, the Meta Memphis pieces still defy easy assimilation into the status quo, gesturing instead towards how things could be. If there is a future for design after the end of history, Meta Memphis might present an escape route from our interminable present Postmodern limbo, offering glimpses of the new to reveal how everything could be otherwise.

Susana Solano, Valigia (1989); Meta Memphis Collection from 1989. Image courtesy Memphis Milano.

SEE THE FULL META MEMPHIS COLLECTION HERE.

Text by Alec Recinos

This story was originally published in PIN–UP 31, Fall Winter 2021/22.