EDIBLE ARRANGEMENTS: How Fruit And Food Packaging Inspire Jonathan Trayte’s Sculptural Furniture

Perhaps no one else uses the language of commercial appliances with the same dexterity as artist-designer Jonathan Trayte — certainly no one else is mining so joyfully in the unpromising territory of food packaging for source material. London-based Trayte has been working with a consistent formal vocabulary since his student days at the Royal Academy in 2010, where his preoccupation with retail marketing strategies began. In his latest show, MelonMelonTangerine, at Friedman Benda in New York, succulent and tree-like forms intersect with brushed steel tubes and illuminated glass fixtures that seem imported from an ecosystem of mall furniture and shopping window displays.

Juxtapositions of color, texture, and reflectivity play up the festive friendliness of Trayte’s compositions. But the easy appeal of his functional sculptures belies their complexity. Trayte’s eclecticism frequently complicates the assumed differences between his materials.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Atomic Double (2020): Bronze, stainless steel, brass, aluminum, reinforced plastics, crushed and blown glass, marble, light fittings, upholstery.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Atomic Double (2020): Bronze, stainless steel, brass, aluminum, reinforced plastics, crushed and blown glass, marble, light fittings, upholstery.

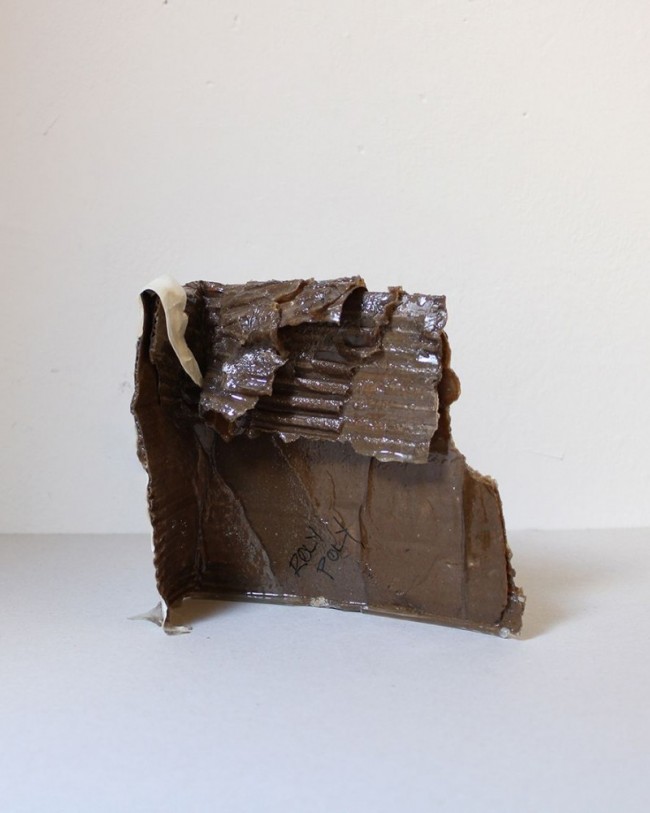

For instance, in Atomic Double (2020), he layers the sheen of brushed steel against the gleam of a resinous surface that appears biologically derived. Closer inspection inverts this impression — the resinous bark, in detail, looks more like dross from an industrial vat. Meanwhile, the resinous tree grows oddly straight while the steel bench grows oddly warped, such that each material exchanges the conventional character of its usage. This indeterminacy calls into question what qualifies a thing as natural or artificial, constructed or grown, and whether these bifurcations are in fact meaningful at all.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Grass Green Settee (2020): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, bronze, marble, polymer compound, pigments, reinforced plastics, crushed glass, animal hide, upholstery, light-fitting.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Kula Sour (2020): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, birch plywood, reinforced plastics, crushed glass, black American walnut, marble, polished bronze, cow hide, wool, upholstery, light fitting.

If the dictum to copy nature has been a guide to artists from the time of Michelangelo to Art Nouveau, Trayte seems more interested in extending our concept of nature to include our own productions — without belaboring easy moralisms about consumerism or climate change. Pollock famously claimed “I am nature.” Trayte’s work suggests that your sofa might be too. In Grass Green Settee (2020), tubular steel supports multiply according to the same erratic principles that might direct the branching of a tree limb.

Trayte’s fondness for neons and eye-popping friendly color compositions are, he says, influenced by advertising. They also call to mind the sculptures of Ron Nagle. While Nagle’s work is miniature and suggests maquettes for architectural scale installations, Trayte comfortably shifts scale from the tabletop to larger public works, as in The Spectacle (2019). Franz West, an acknowledged influence, also comes to mind — but while West combined his haphazard candy-hued forms with a comically monumental gravity, Trayte anchors the humor of his work in unexpected material equivalencies (see the orange fur, orange steel, and golden bronze elements conjoined to form an armrest in MelonMelonTangerine, 2019). Again and again, Trayte incites and then subverts the expected associations of a given material/form relationship.

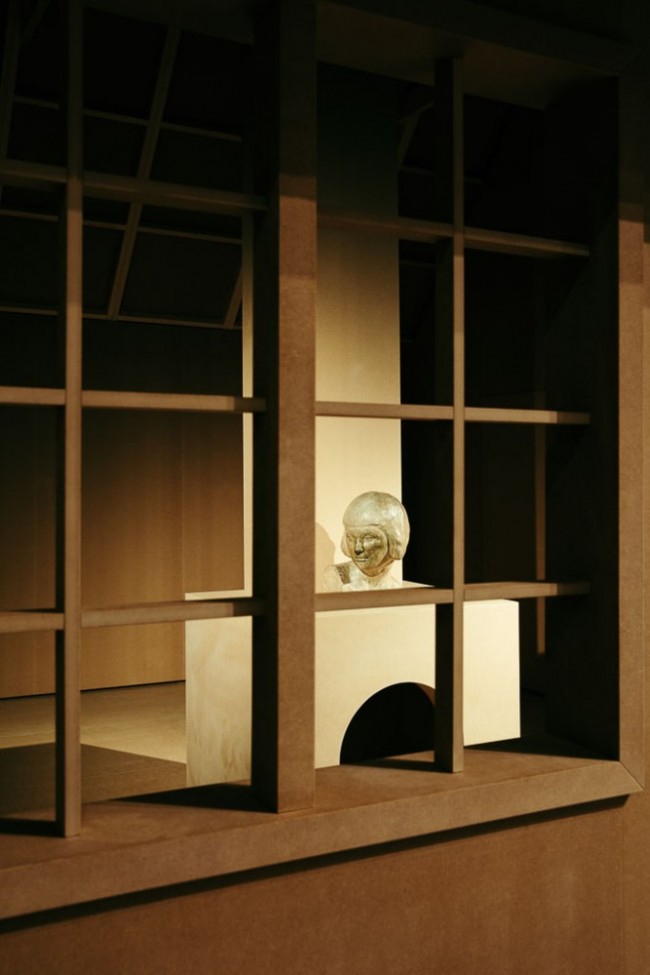

Jonathan Trayte, The Spectacle (2019), a site-specific installation comprising of seating, lighting and sculpture, situated in a busy thoroughfare for pedestrians and functioning as a meeting place or somewhere to pause.

One of his favored surface treatments is flocking, a material composed of loose short rayon or nylon fibers. This is applied in an even coat that is fur-like and almost repulsively chemical at once. Trayte has cited food packaging as a continual source of aesthetic influence — and this itself is telling. Why food packaging, and not any other packaging? Because food packaging involves an interesting convergence — bags of oranges are covered with images of even more delicious looking oranges because it is the representation that makes the reality palatable — advertising draws these otherwise frighteningly inhuman things into our sphere. This human-led marketing to promote consumption is itself an extension of the advertising fruit and vegetables undertake of their own initiation — by making themselves as brightly enticing as possible they lure in potential seed carriers. Yet another way human and natural projects are not so divergent as we might assume.

-

Jonathan Trayte, MelonMelonTangerine (2019): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, birch plywood, upholstery, leather, animal hide, marble, granite.

-

Jonathan Trayte, MelonMelonTangerine (2019): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, birch plywood, upholstery, leather, animal hide, marble, granite.

One of Trayte’s most enjoyable maneuvers is to have one function interrupt another — a floor lamp pierces through a settee (Mint Rola and Lamp, 2018), a structural leg bends up through the surface of a table (Tropicana, 2016), a table is broken apart by a light (Pink Kiri Candy, 2019). This too has the flavor of advertisement about it — as though the Mint Rola settee grew anxious and sprouted other functions before an audience could cease being interested in it. Trayte’s energetic compositions have the stumbling-over-themselves urgency we are used to in commercials — like hyperbolic examples of a “feature added” retail strategy whereby goods will proliferate into greater usefulness until toasters can perform all the functions of surfboards and air conditioners. This rampantly innovative spirit runs throughout his oeuvre — as indeed it runs throughout the natural world and the laissez-faire spirit of the free market — each with its tendency towards schizophrenia and cannibalistic renewal.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Mint Rola and Lamp (2018): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, bronze, marble, granite, birch plywood, animal hide, fabrics, upholstery, light fitting. Photography by Timothy Doyon.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Pink Kiri Candy (2019): Marble, granite, limestone, sandstone, basalt, powder coated steel, stainless steel, aluminium, reinforced plastics, pigments, crushed and blown glass, light fitting, power pack. Photography by John Hooper.

The presence of choice is constantly highlighted in Trayte’s work — which brings into focus a thousand instances of decision. Whereas the form of say, a Henry Moore sculpture might attain a certain cohesion and be approached as a dynamic monolith, Trayte’s work is legibly tweaked, altered, and revised and the connections between each impulse is painstakingly detailed. A leg becomes an arm becomes a headrest — and these transitions are performed in public (see bONZA, 2020). Sometimes we can see the joining screws, bolts, and brackets — sometimes there is no evidence of how the work has been put together. The result of making in this way, in which there are no clear principles the artist obeys regarding constructive methods, is that each individual moment is blistering with choice and no form develops the feeling of inevitability that artists of cohesion pursue. Trayte’s works are accretions of decisions and contingencies, just as trees are inflected by the varying conditions of soil, light, and rain — continually adapting their strategies for growth.

-

Jonathan Trayte, bONZA (2019): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, birch plywood, upholstery, animal hide.

-

Jonathan Trayte, bONZA (2019): Powder-coated steel, stainless steel, birch plywood, upholstery, animal hide.

Once we get used to seeing steel benches made a certain way, we begin to feel that something is unnatural about a bench made differently. Likewise, machine reproduction has conditioned us to instinctively categorize organic, undisciplined shapes as natural — but if we look more closely we find that this guidance is faulty. Joshua trees, the real ones, aren’t any less disorientingly composed than Trayte’s representations — they burst into sudden foliage at their tips and their thick hairy limbs grow, improbably, from similarly thick hairy trunks. Their silhouettes are clear, as though drawn by sharpie — and they waste no energy on twigs and small exploratory branches. Gaudí said, “There are no straight lines or sharp corners in nature.” But that was true only until nature produced humans. Trayte’s work suggests that the anthropocene is no less artificial than previous epochs — that trees and hollows, the furniture of wildlife — is not so distant from even the most quixotic of our domestic contrivances.

-

Jonathan Trayte, Pink Hot Solar Buzzer (2) (2019): Stainless steel, polymer compound, reinforced plastic, pigments, glass, nylon flock, brass, light fitting.

-

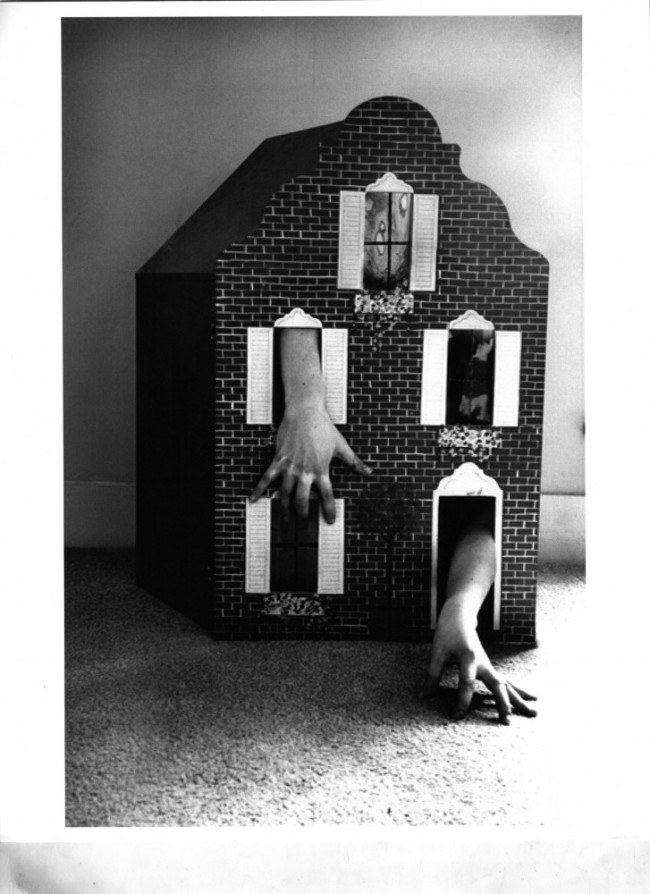

A Joshua tree also known as a yucca palm. Image courtesy the writer.

MelonMelonTangerine at Friedman Benda gallery February 18 to March 13, 2021.

Text by Brecht Wright Gander.

Images courtesy Friedman Benda and Jonathan Trayte.