ESSAY: The Eternal Return of the Primitive Hut

“Earth is always-already architecture.” — Peter Carl

“We flee in thought in search of a real refuge.” — Gaston Bachelard

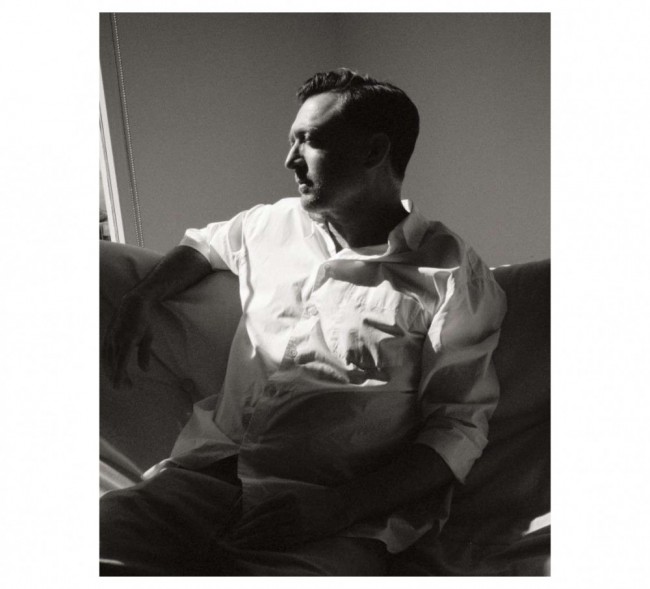

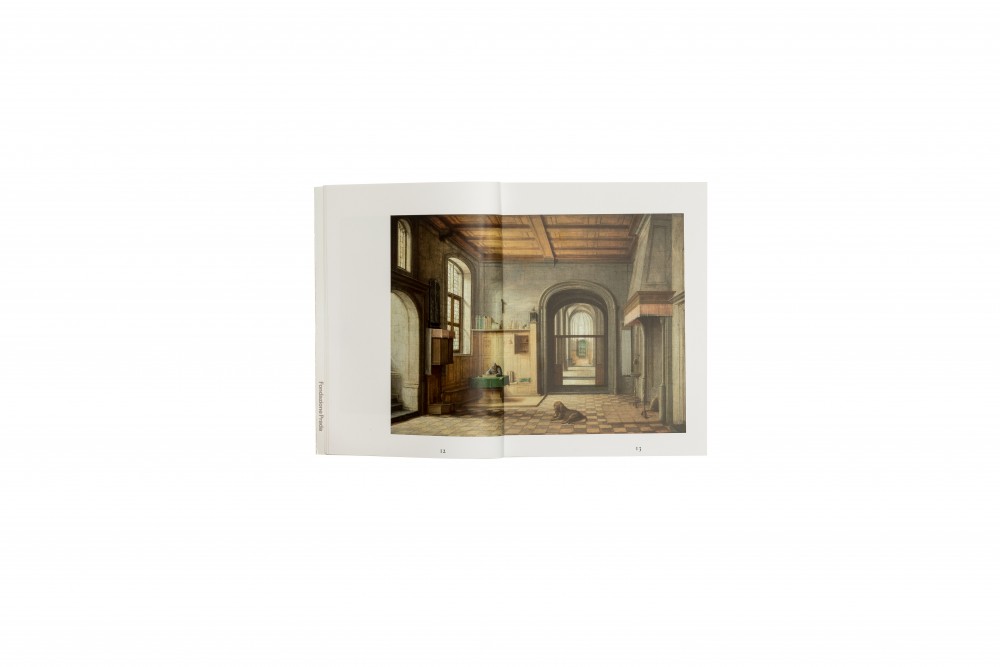

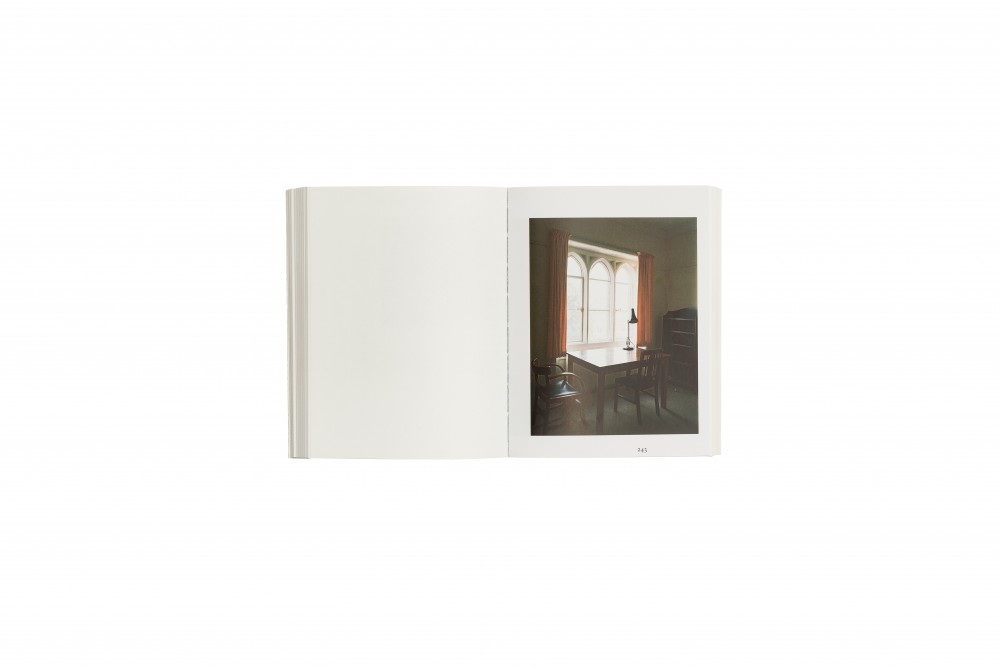

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. In the foreground: Leonor Andunes, One/twelve Knots with Double Impression, (2018). In the background: Mark Riley, Skjolden Diorama (Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Hut), (2016). Reconstruction of Wittgenstein’s hut.

Imagine a field. Not an extraordinary field. Just a field. Grass, yes. Trees in the distance, also yes. A tempered blue sky, a few clouds, birds flying from season to season. No one has lived in this field. Not in recent recorded memory. This is an unspoiled field, the kind conjured by middle class- imaginations when image searching for “nature.” There’s silence, but it is not the silence of God abandoning earth. It is the silence of the not-city. There are no roads, no cars, no Starbucks, no automatic sliding doors, no security cameras, no imposing reception desks in stark office lobbies, no windows locked shut, no sticky linoleum, no Mickey Mouse gargoyles, no marble slabs of boutique shelving, no subsided brick walls, no wheezing air-con, no nicotine stained ceilings, no dusty vitrines, no talking toilets, no fascist fenestration, no storage cupboards and their secrets, and definitely no soaring spires. There is no architecture.

But what if you wanted architecture to appear on this field. With the minimal effort. The minimal means. What would that be?

A wooden floor the size of a small room? Walls arranged around it? A door to enter? One or two windows? A roof? Because, at some point, it will rain. It might snow. And so, we might wonder, is that gathering of elements the most minimal architecture?

The name for such an assemblage may be a “hut.” A single syllable word, as simple as a child’s outline for a house. Basic shelter, yes, undoubtedly, for the earth’s inclemency is felt across most of its inhabited surface. Protection from outside threats — wolves, thieves — that too. However, the persistence of the hut in the history of architecture and culture suggests, very strongly, that its true symbolic significance vastly eclipses its modest, pragmatic pretense. And size.

In Joseph Rykwert’s landmark essay, On Adam’s House in Paradise (1972), the hut is introduced as the very first dwelling in the Garden of Eden, inseparable from the bounties of fruit yielding trees. And although the Book of Genesis makes no specific reference to Adam and Eve’s house, Rykwert contends through extrapolation, that it must have been there, as much a “promise as well as a memory.” The hut, as an archetype, contains multitudes: ghosts of pasts, and shadows of those ghosts that loom into the future. According to Rykwert:

(...) the return to origins is a constant of human development. The Primitive Hut — the house of the first man — is therefore no incidental concern of theorists, no casual ingredient of myth or ritual. The return to origins always implies a rethinking of what you do customarily, an attempt to renew the validity of your everyday actions.

In what forms, and at what times, has the hut appeared as an effort to house thought? How did it persist over advancements in society, belief, technology? And what is it hiding? Or, what is it hiding from?

Alone with God

Imagine climbing to the top of a ruinous column, in the desert heat of the Eastern Roman Empire, 5th century CE. There, you will stay for 37 years, in abstemious devotion to God. Your name is Simeon Stylites, and, one day, you will become a saint, in recognition of your extreme privation, and much time after that, Luis Buñuel will make a feature film based around your life, called Simon of the Desert.

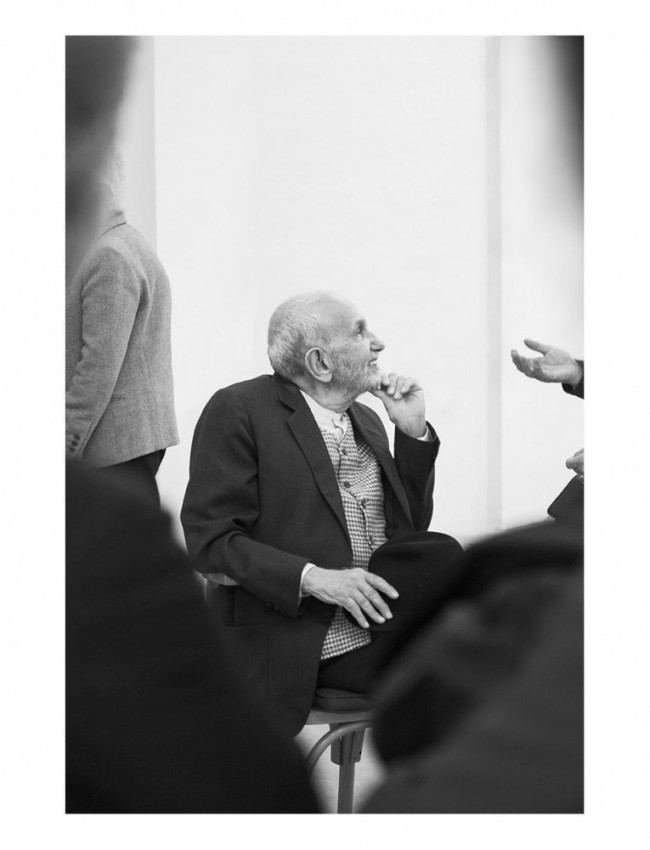

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. Paolo Chiasera, Spazierstock, 2009.

Simeon’s retreat from the city followed the practice of the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers, early Christian hermits, ascetics, and monks who lived mostly in the Scetes desert of Egypt beginning around the 3rd century CE. The best known of these is Anthony the Great, who became the father of desert monasticism. He chose to follow the example of Christ, and disavow his wealth and material belongings. In return, it is said, God gave him special privileges, such as the ability to heal the sick. By the time of Anthony’s death in 356 CE, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to a similar calling. Anthony’s biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, wrote that “the desert has become a city.”

The Desert Fathers and Mothers had a profound influence on the early development of Christianity. They shaped the way for monasteries to emerge, as isolated communities defined by what was made absent. Isolation and privation — an awayness — became the premise upon which exceptional spiritual access (to divine wisdom, or future heavens) was transacted. As Gaston Bachelard said, “The hermit is alone before God.”

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Head of a girl, 1925–28.

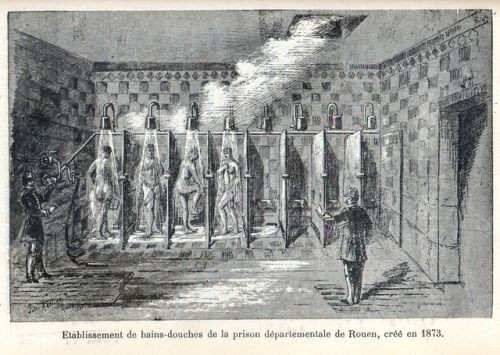

The irreducible unit of the monastery was the cell: a tiny, bare room, pierced by a small window set high on one wall, through which commune with God could take place. The monastic cell was its own hut.

At the very end of Buñuel’s film (which was released in 1965), after several failed attempts to break Simon’s resolve, Satan transports the two of them to a 1960s nightclub. There, young people are dancing maniacally to a song called “Radioactive Flesh.” It is, perhaps, the absolute antithesis to Simon’s decades alone atop of the column, or, when he hid away in a hut for few year, an act people considered a miracle. Simon tells Satan he wants to go home, back to the desert, back to the minimal means of existence. But Satan says he cannot.

Alone with Knowledge

Imagine a palace in 15th-century Urbino. Its impressive hallways and staterooms, where decrees may be signed, and wars weighed. In the center of this palace is a small chamber. It is set aside for study and contemplation. Its walls are made from marquetry and intarsia, and depict, in trompe l’œil, shelves, benches and half-open doors containing symbolic objects representing the Liberal Arts. You are Duke Federico III da Montefeltro, and every day, your routine consists of reading Greek literature, visiting the lararium, and devoting yourself to Classical studies in this studiolo.

These rooms became popular during the European Renaissance. It signaled that the owner was especially cultivated: in philosophy, astronomy, mathematics. As such, the studiolo’s walls were meticulously inlaid with depictions of musical instruments, books, astrolabes, etc. The use of perspective in the marquetry or intarsia creates depth from flatness, of course, but also introduces a realm of illusionand latency. The studiolo was theatrics. A stage-set for the (re-)making of a character. The owner would meet with their tutor in this space. Here, they would turn away from daily duties — as businessman, military leader or head of state — and turn inwards, towards the space of knowledge. In Duke Federico’s case, his studiolo turned away from the city of Urbino, and faced his rural lands, suggesting that introspection is oriented towards awayness, towards nature.

In a letter to his friend Francesco Vettori, Machiavelli described the kind of personal retreat his studiolo represented:

When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them... Then I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives for their actions and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexations, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass into their world.

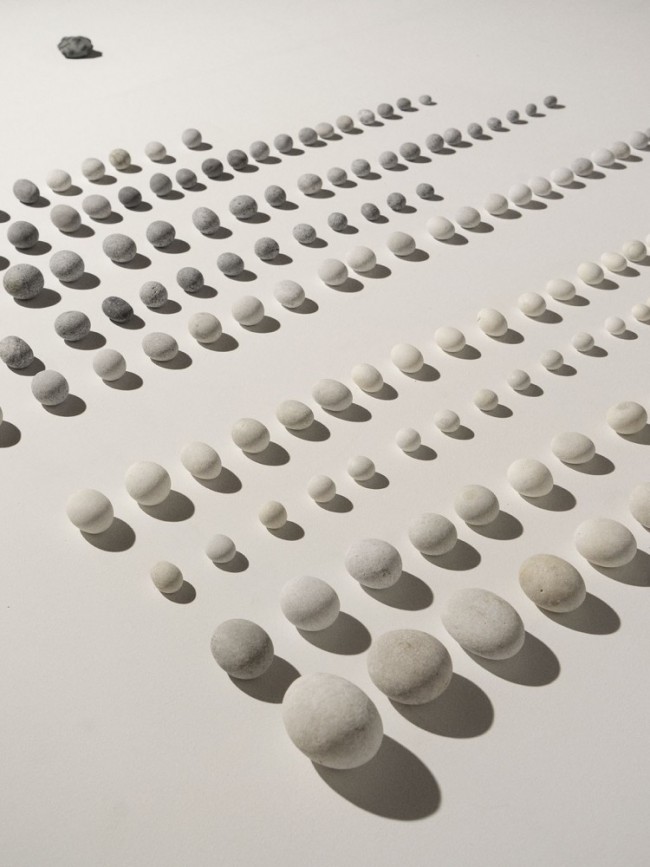

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. In the foreground: Leonor Andunes, One/twelve Knots with Double Impression, 2018. In the background: Mark Riley, Skjolden Diorama (Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Hut), 2016. Reconstruction of Heidegger’s hut.

Two famous paintings of a studiolo are Antonello da Messina’s Jerome in His Study (c. 1475) and Vittore Carpaccio’s Saint Augustine in His Study (c. 1502). In both, we see an elaborate constellation of objects, furniture, books and animals, all deeply recessed in spaces that exclude the outside. For, like the hut, the studiolo was an intense cosmos of interiority, one engineered specifically towards rarefied thinking. A retreat into a private zone of worldly knowledge, where transformation — of the mind, the soul — was possible.

Alone with Nature

Imagine a forest. You choose to bed here for the night. There are four trees, similar in height and form, close to one another. You tear off some sturdy branches. Array them across the tops of the trees, forming a frame. The other stripped branches, you set at a pitched angle to one another. Leaves are your roof tiles. Now you are ready to sleep.

In 1753, Abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier published *Essai sur l’Architec*ture. Three years earlier, Jean-Jacques Rousseau published the first of his treatises on the corrupting forces of civilization upon human beings, Discours sur les sciences et les arts. Like Rousseau, Laugier sought a way out of the current cultural moment, which, in France ’s architecture at that point, had become dominated by the Baroque: excessively ornate, and, in Laugier’s opinion, removed from the fundamental program of architecture: to shelter.

Laugier returned to Vitruvius, a 1st-century-BCE Roman civil and military engineer, whose De architectura is considered the earliest intact writing on the decorum of architecture, and served as canonical from the Renaissance onwards. Updating Vitruvius’ triad — firmitas, utilitas, venustas (solid, useful, beautiful) — Laugier sought his creation myth in what nature had to offer:

The man is willing to make himself an abode which covers but not buries him (...). Pieces of wood raised perpendicularly, give us the idea of columns. The horizontal pieces that are laid upon them, afford us the idea of entablatures (...). The little rustic cabin that I have just described, is the model upon which all the magnificence’s of architecture have been imagined.

But, it was the second edition of Essai sur l’Architecture, published in 1755, that crystallized Laugier’s words into a single compelling image: Charles-Dominique Eisen’s allegorical frontispiece shows a young woman pointing at a “primitive hut.” The hut is embedded in trees, assembled from branches; a kind of associative apparition that synthesizes found nature with human intent. In pointing didactically, instructing a young child next to her, the message is clear: this is the way. This is the model of excellence. A return to origins during the Age of Reason. Architecture “discovered,” rather than invented, whose moral virtue was thus entwined with the prelapsarian status of nature, “primitive man” and modesty. As Giambattista Vico, the Enlightenment thinker put it:

Philosophers and philologists should be concerned in the first place with poetic metaphysics; that is, the science that looks for proof, not in the external world, but in the very modifications of the mind that mediates on it. Since the world of nations is made by men, it is inside their minds that principles should be sought.

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. In the foreground: Mark Riley, Skjolden Diorama (Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Hut), 2016. In the background: Reconstruction of Heidegger’s hut.

Alone: A Lifestyle

Imagine calling up Muji, because, you read this (on their website)(hiips://www.muji.com/jp/ mujihut/en.html), and, you want to make an order:

Who hasn’t dreamt of living somewhere they really want to be? The tools to make that dream a reality are now available. It’s not as dramatic as owning a house or a vacation home, but it’s not as basic as going on a trip.

Put it in the mountains, near the ocean, or in a garden, and it immediately blends in with the surroundings, inviting you to a whole new life.

This was the vision behind our radically new “MUJI Hut” concept. — muji.com

Costing 3,000,000 yen, the MUJI Hut is a prefabricated single room unit finished to the same perfection as a Muji stationery holder. It doesn’t come with somewhere to put it — that is your responsibility — but it does come with a very contemporary fantasy: to escape roads, cars, Starbucks, automatic sliding doors, security cameras, imposing reception desks in stark office lobbies, windows locked shut, sticky linoleum, Mickey Mouse gargoyles, marble slabs of boutique shelving, subsided brick walls, wheezing air-con, nicotine stained ceilings, dusty vitrines, talking toilets, fascist fenestration, storage cupboards, and soaring spires. To escape architecture.

Exhibition view of Machines à penser, Fondazione Prada, Venice. Photo Mattia Balsamini. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. In the foreground: Leonor Andunes, One/twelve Knots with Double Impression, 2018. In the background: Mark Riley, Skjolden Diorama (Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Hut), 2016. Reconstruction of Wittgenstein’s hut.

Never Alone Again

The hut — “primitive” or otherwise — may be the first conceptual architecture, as much as the first concrete architecture, because, as we have seen, it is the basic unit of architecture thinking about itself. A mono-syllabic, ur-thought. It contains a multitude of fantasies and is comprised of a history of intellectual fantasies, some of which have been outlined in this text. The hut is the threshold between nature and not-nature, regardless of whether nature itself mutates into something altogether artificial, augmented and irreparable, as it is today. Indeed, the hut is a quantitative constant against the chaos of change — a veritable eye of the storm — and it is this supposed immutability that has rendered it perennially relevant. Will this fantasy persist for future philosophers? Will they, too, crave self-exile, in order to turn inwards, to some ineffable essence, from which thought can speak? I can’t imagine a so-called “accelerationist” choosing this as their mythos anymore, even though they may well holiday on a remote Greek island in the summers. Perhaps simply choosing to cut off your Wi-Fi, or smashing your smartphone with a rock, will deliver the same results as cultivated removal once did. At this point, the hut is no longer made of wood, but rather, the articulated destruction of here-ness.

Text by Shumon Basar.

This is an abridged version of Shumon Basar’s essay The Eternal Return of the Primitive Hut. The full version can be found in the book Machines à Penser that accompanies the exhibition of the same name curated by Dieter Roelstraete at Fondazione Prada, Venice.

Machines à Penser is on view until November 25, 2018. To pre-order the the book (available in the U.S. on August 28), please click here.