Interview with Robert Yang, Designer of 3D Fantasy Sex Spaces

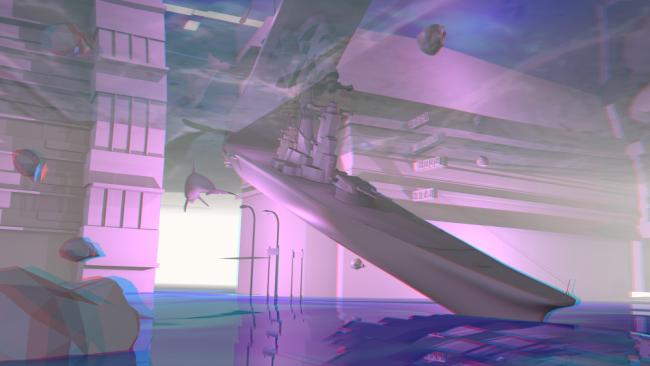

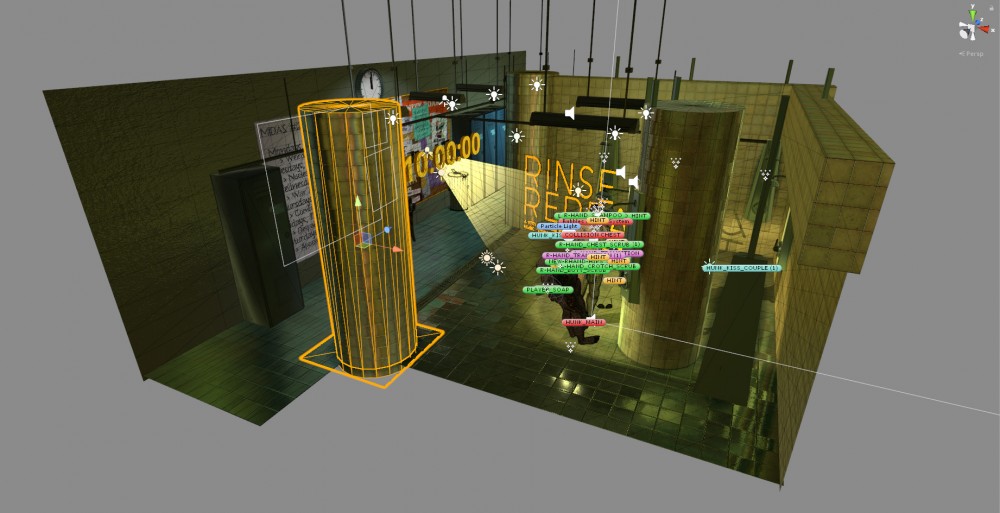

Prototype for crowd simulation AI in The Tearoom.

In the popular imagination, video games are the preserve of solitary nerds shooting at 3D bad guys in fantasy environments, not the domain of radical sex positivity — let alone radical gay-sex positivity. But there is in fact a rich culture of independent game developers dreaming up all manner of out-of-the-box interactive realities. 29-year-old Robert Yang is one of them. The man behind cult-favorite gay games such as The Tearoom (2017), a 3D bathroom sex simulator, Rinse and Repeat (2015), a male shower simulator, and the gay-sex triptych Radiator 2 (2016, a compilation of three previously released shorts) is also an assistant arts professor at New York University’s Game Center, a locus for both game development and theorization. Not only that, Yang has an architectural pedigree, having lectured and published extensively on architecture and furniture design in games, including a contribution to Elements of Architecture, the book that accompanied the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale.

In your discussions of level design (a game-development discipline involving the creation of video-game levels, locales, missions, or stages), you’ve said that you don’t feel game designers look at buildings. What could they gain from studying them?

Architecture in video games is worse than high Modernism. It’s a really specific idea of how we build the 3D world — just for the player. There’s also no wider dialogue about the politics of the spaces being built. It’s like, “Oh, let’s build a war-torn Iraq, let’s fantasize about the Arab world being destroyed and we’ll shoot each other in it.” There’s this assumption that it’s all just fun and entertainment.

Why the emphasis on level design?

Part of it comes from how video-game design evolved. It’s really hard to do good characters — where both writing and rendering are concerned — that aren’t creepy or weird. In the absence of good characters it’s much easier to render a nice tree, or a nice rock, or a chair. To me level design feels like the purest aesthetic you can find in a video game. It uses the direct simulation of space to make you feel something or think something.

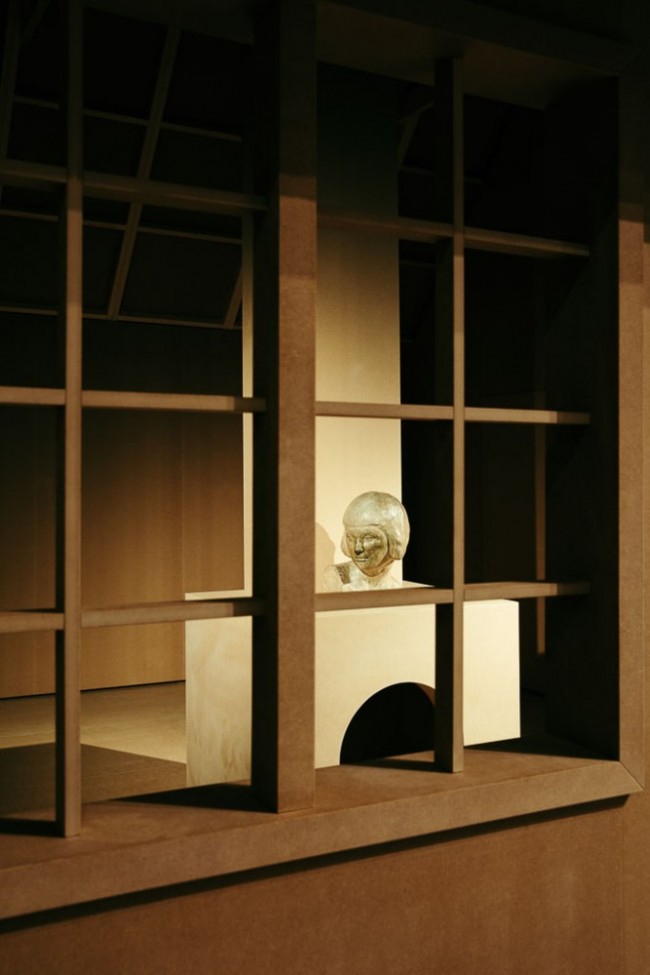

Set construction in Rinse And Repeat.

The aesthetic of your levels is very similar to a lot of the mass-release first-person shooters that make up the majority of the commercial video-game market. What made you choose this look?

I try to produce these games in an aesthetic that’s very contemporary with respect to what video games look like. Which is unusual. Most games that deal with queerness and gayness usually stay away from mainstream aesthetics, either because they don’t have the resources or production ability or training, or because they don’t like it and they think it’s gross. But I feel that when these games look like video games, it makes you wonder why there aren’t commercial video games with content and gameplay like this. That’s why I throw everything into producing these shorts that have the graphic quality of a commercial video game. They’re generally about two minutes long, which is all I can manage on my own.

What does this blockbuster aesthetic mean for your own level design?

In my own gay-sex games, the level design is strange because I approach it more like a film set. I build half of a room instead of a whole room. I’m designing everything to be perceived from one point, and the camera can’t move — it can barely turn around and see what’s behind it. It’s super constrained and controlled. In video games we often say that we want to give players all this agency and freedom, but ultimately it’s fake freedom, and I don’t want to indulge that.

"Meat to metal" shader transition for "Obrez" type gun (model by Pen Ward) in The Tearoom.

How does this read with the fact that most of these games are first person?

I’m trying to tap into the double sense of first-person-ness and of playing, of you being both a player and of being played in some way. These games wonder what the first-person perspective projects back onto you as a player in a wider sense.

There’s also the issue of voyeurism: the player is watching the content of the game, but is often being watched in the narrative as well, such as by the hidden camera in the The Tearoom, or the recurring threat of police.

Not only that, but the player is being viewed playing the game itself. In gamer culture at large, making games about gay subjects is still an oddly controversial thing. If I show these games at public events then this straight gamer guy is worried that people will see him enjoying this gay sex game; he’s aware of being seen. He’s aware of being seen seeing something else being seen, all those layers. I want to facilitate those layers of vision and comfort and discomfort.

Set construction in The Tearoom.

Returning to the politics of architecture, or the politics of space, you explicitly acknowledge that making space is always a political proposition, even in video games. Given that there are virtually no gay games, how does that read with your notion of rendered environments as always already political?

I think of architectural intervention as taking place beyond these more literal, representative spaces. I also imagine gamer culture as an architectural space that I can invade. When I have a 3D gay sex game on (popular game download platform and gamer community) Steam, that upsets gamers on this visceral level where sometimes they can’t even articulate what’s happening for them.

Are you trying to direct the player’s emotions, or are you just sitting back and watching?

I always try to direct the player’s emotions to some sort of political point, whether it’s police interrupting you having sex with your car in Stick Shift, or the government stealing all your dick pics in Cobra Club (both first released in 2015), or the police intervention in The Tearoom bathroom cruising game.

Do you expect people to get off on your games?

One cool reaction I had was a player who posted a video of himself masturbating to my game on Xtube. Weirdly enough, Xtube kept taking it down — Xtube was censoring porn! (Laughs.) But I really like the idea this guy was trying to jack off to my game, because I don’t think of my games as super arousing. Maybe it’s because I stare at them for thousands of hours.

Urine physics simulations in The Tearoom.

So much of video-game design seems to be about fantasy, whether a new fantastic world or just sexual fantasy. What is it that you’re trying to make happen in your alternate realities?

In video games we have this idea of the magic circle, which represents the boundary between people who aren’t playing the game and those who are. If you’re playing football and you tackle someone, that’s okay in the magic circle. But if you tackle someone on the street who didn’t consent to play football with you, they were outside the magic circle. And it’s precisely this boundary or membrane between the game and reality that I want to break and puncture. Usually that puncture happens at the end of my games. It’s the game saying, “No, this is reality bleeding back into the fantasy.” It’s showing you that the fantasy can’t just be taken as a fantasy, you always have to situate it within the world.

Can you give an example of a moment when that puncture happens in one of your games?

In my spanking game, Hurt Me Plenty (2014), you can spank the character, but if you violate the boundaries that they agreed upon or you spank them too hard or you ignore when they invoke their safeword, the game will refuse to play with you. That violates what video game culture expects from the magic circle, which is that a computer is always available to work with you and play with you. A person can refuse to play with you. A computer is always supposed to be available. This notion bleeds into a lot of problematic attitudes about sex, that certain people are there to dispense sex for you. I wanted to attack that attitude by creating situations where a computer would refuse abuse. I’m dealing with the materiality of the game in order to puncture that magic circle and to shake the player. The game has memory. It remembers what you did — that exact second, that exact millisecond when you violated its trust. And it will remind you,

Set construction in The Tearoom.

You’re using seemingly pretend, virtual play to disruptive affective and political ends IRL. In what way can this be politically or emotionally useful?

Everyone who plays a game is kind of doing performance art, which is important. Play encourages you to perform in a way that I think a lot of people are otherwise too self-conscious for. The idea that you can get into watching a hunky dude eat a popsicle, for example, and that’s a performance in itself. In games we call this “getting really into it,” into the lusory attitude. It’s when you open yourself up to that playful attitude that the game is trying to facilitate. I like what it does to your state of mind. Some really good games are almost meditative.

Is the effect lasting?

Yes. Video games reprogram their players to think in certain ways. They reconfigure you. You perform within their space, you leave the game but you still have it with you a little bit. And ideally it’s a good thing that you carry back.

Can that not be said for all types of fiction? Or is the way games do this unique?

In the general sense, no, this is what all art does. Books certainly simulate space, films certainly simulate space, but it’s always abbreviated or punctuated. In a game space is almost always continuous, possibly to a fault. So from my elitist video-game perspective, I do think the effect is stronger with games. Maybe it’s because you’re actually performing the gestures or because it simulates a literal space. Video games often simulate every boring part of a house, even the bathroom, while a book or a film isn’t going to bother with that.

Urinal flush effects in The Tearoom.

Speaking of bathrooms, there are a lot of them in your games. Why do you want to keep putting people in the bathroom?

Often in game design the bathroom is just there to show off. They’re very shiny — shiny chrome fixtures, beautiful tiles, all there to show off your graphics technology. I’m plugging into that tradition while also associating it more explicitly with gay sex. I’m trying to say, “Look, I made the most sophisticated video-game bathroom ever and I’m just going to have gay sex all over it.” So that people will think, “Oh yeah, what’s an interesting bathroom in a video game? The best one was that gay-sex thing.” I hope it gets lodged in their memory.

The bathroom was just the textbook afterthought people used to show off their game’s realism, and now the bathroom is totalizing, it’s just everything.

It’s the entire world, literally.

Do you consider the worlds of your games, bathrooms or otherwise, ideal worlds?

Sometimes they are. The dick-pic game Cobra Club is fairly idealized in that it imagines men of all types producing dick pics to validate each other’s body images. That’s a pretty ideal world compared to the reality of dick pics. My games imagine or propose sexual worlds. The idea that you can eat in a sexy way or the idea that you should take kink seriously — that kink actually formalizes consent in a really great, interesting way — are useful takeaways that I hope players get. That “Oh, I never thought of sex in that way” or “I never thought of driving in this way.” So hopefully, yeah, even driving becomes a sexual experience for some people.