Piano Non Forte: The Work of Renzo Piano Building Workshop at The Royal Academy

Brian Eno, in a recent conversation with Finn Williams at the British Library, reiterated his notion of the “scenius”, that ecology of ideas and individuals, rather than lone geniuses, that give rise to cultural movements and moments: the Bloomsbury group, the Bauhaus, Detroit house. “We have grown up with this notion of genius, that there are these gifted individuals walking round changing everything” Eno said. “But the closer you look at a cultural situation, the less easy it is to distinguish and separate out these key figures.”

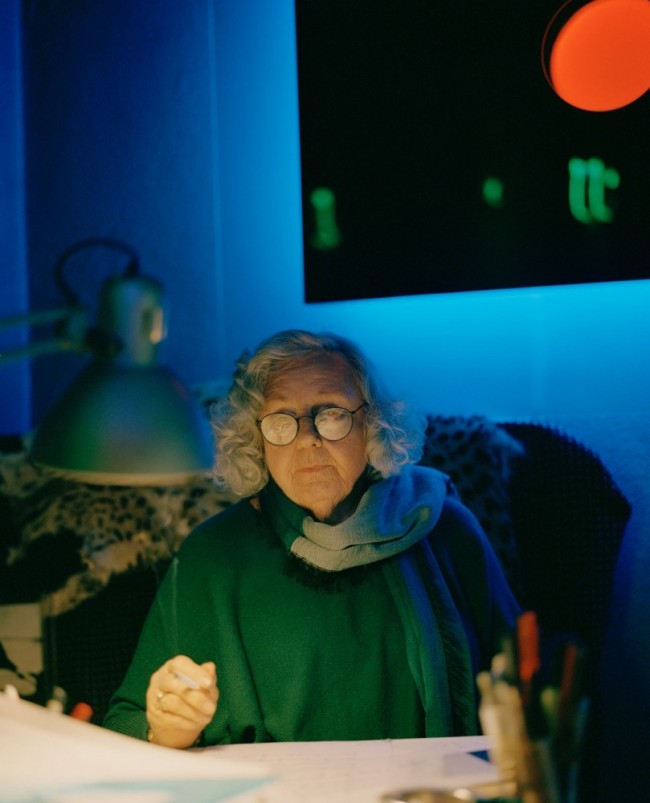

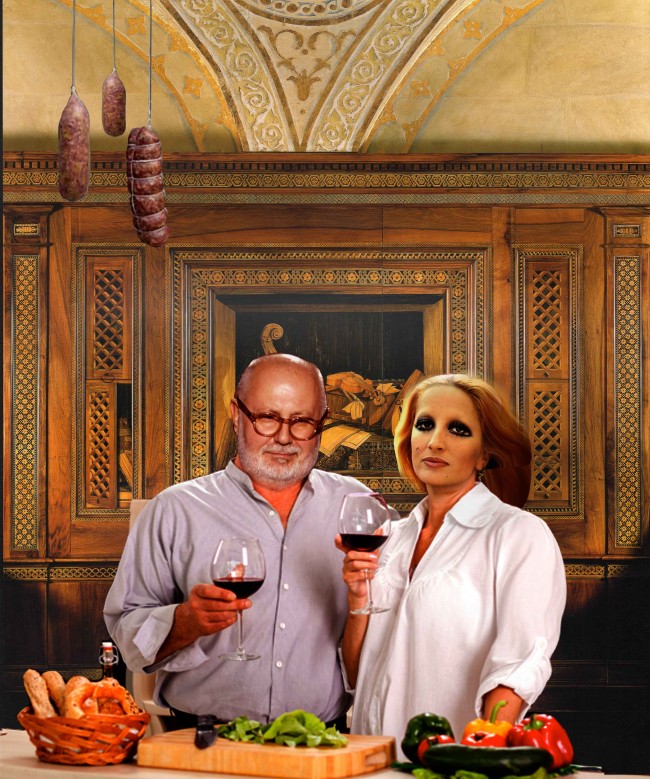

Portrait of architect Renzo Piano amid The Art of Making Buildings, an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, showcasing the work of his firm Renzo Piano Building Workshop. © David Parry/Royal Academy of Arts

Funnily enough, Renzo Piano was not at this discussion. Across town, Piano’s exhibition The Art of Making Buildings at the Royal Academy of Arts, curated by Kate Godwin in collaboration with RPBW, exudes a different kind of sentiment. Here, amidst detailed models of buildings and complexly engineered construction parts, a collection of Air France napkins epitomize the tired air of heroic, male genius that surrounds the Italian octogenarian. The early forms of Kansai International Airport, Osaka, or the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, Athens, appear in hasty sketches captured in a fit of inspiration, presumably aboard a plane, placed delicately in the covered desk displays like a discarded Rembrandt scribble.

Piano’s handiwork appears regularly across the exhibition, which spans three rooms of the recently refurbished Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, in an attempt to solidify the connection between the creative mind and the gargantuan buildings that Piano’s firm designs. Sixteen projects are displayed individually across desks in the first and third room. Displayed in this way, projects are viewed in isolation as decontextualized objects. Like Piano’s buildings, they have little to say to what’s going on around them — focused instead on the marvel of their own engineering acrobatics.

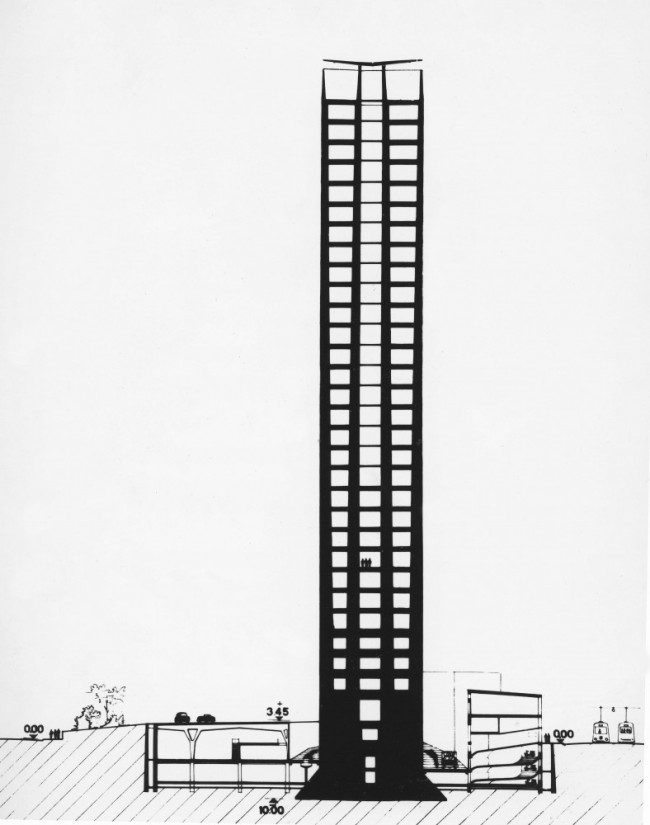

That’s not to say these aren’t often impressive moves. We know that RPBW make spectacular buildings and the exhibition provides a rare opportunity to experience them in a new way. The Shard, omnipresent on the London skyline, is usually hard to fathom as anything other than a silhouette. In the exhibition, one gets a sense of its materiality and sees it in new perspectives — a particular highlight of the show is a photo book of black and white photos showing construction workers putting together the skyscraper.

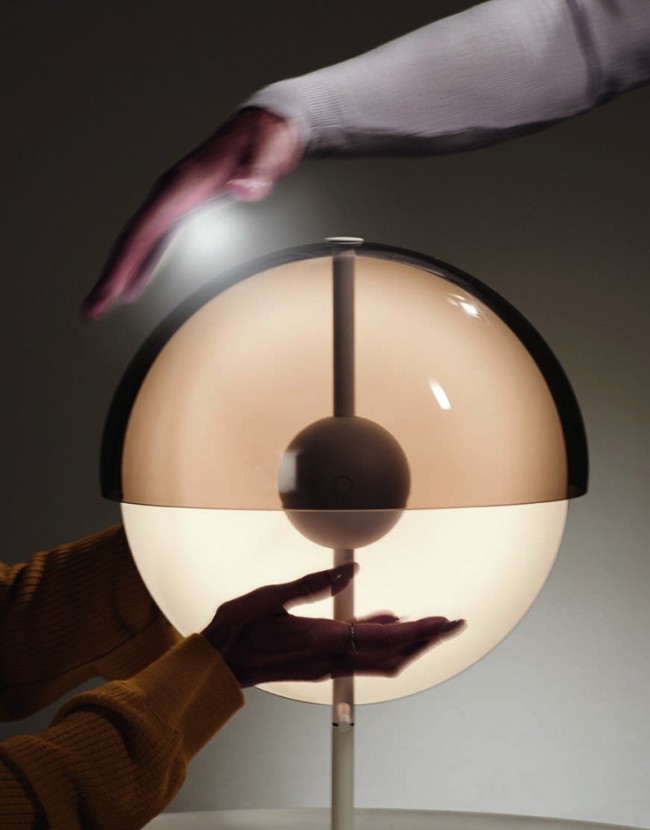

The Island of Renzo: models of RPBW’s most well-known projects gathered together on a wooden platform. © David Parry/Royal Academy of Arts

In the show’s central section, a newly constructed wooden sculptural object shows models of Piano’s projects gathered together in an imagined island. It’s a hilarious confirmation of Piano’s sense of his own aura — a Randian landscape in which the needs, desires, even existence of others are eliminated. It’s also an indictment of the projects themselves — so disconnected are they from their locales, that Piano himself can imagine them uprooted and transplanted to the Island of Renzo. What’s more, once on the island, the projects are scattered around (via what appears to be some dreadful urban planning) in isolation — the object, indeed the exhibition as a whole, seems to say little other than Renzo Piano has built quite a lot of things, and here they are.

Text by George Kafka