THE CACCIA EFFECT: Milan’s Hidden Master of Design and Architecture

Every field — and the inherently linked fields of architecture and design are no exception — has figures who prefer to work behind the scenes, and one might say that these veiled protagonists are the real driving forces. As is the case with the phenomenon of the “artist’s artist” — a Mike Kelley, as opposed to, say, a Jeff Koons — it is always interesting to focus on “architect’s architects,” those who develop their ideas in relative isolation, removed from the noisier theaters of public acclaim. In the majority of cases, their inquiries have a deeper impact than those pursued by more visible practitioners, since these lesser-known figures tend to perfect their radicalism before anyone else, and do so with a more profound experimentalism. Such a figure was Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Milan’s, and quite possibly the world’s, oldest practicing architect until he died, two years ago (on November 13, 2016), aged 103, as one of Italy’s greatest.

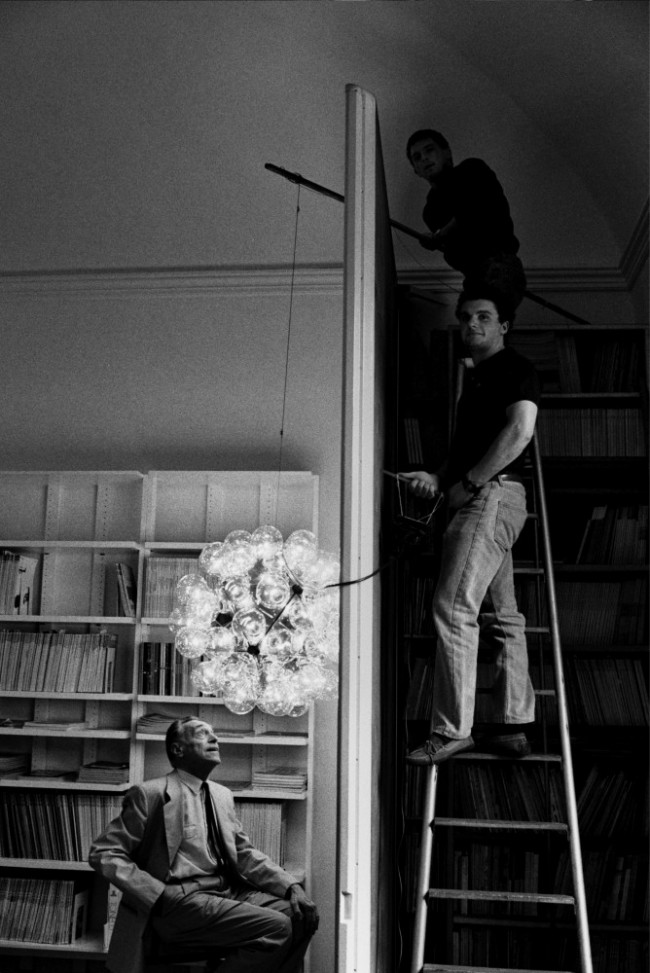

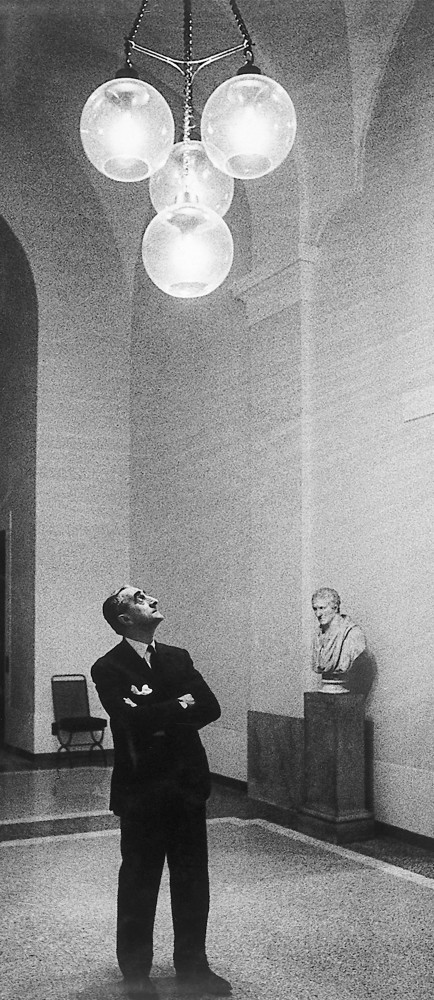

Caccia Dominioni looking at one of his four-globe Grappolo lamps. Portrait originally published in L’Uomo Vogue, March 1967: “A true aristocrat from head to toe” © Ugo Mulas

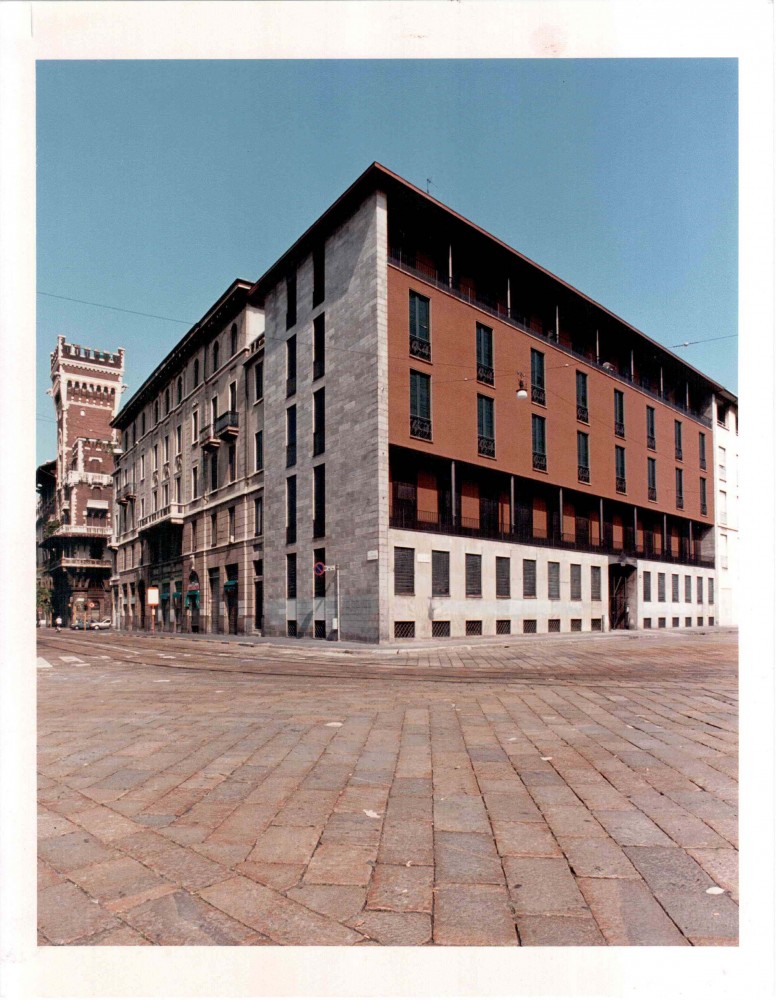

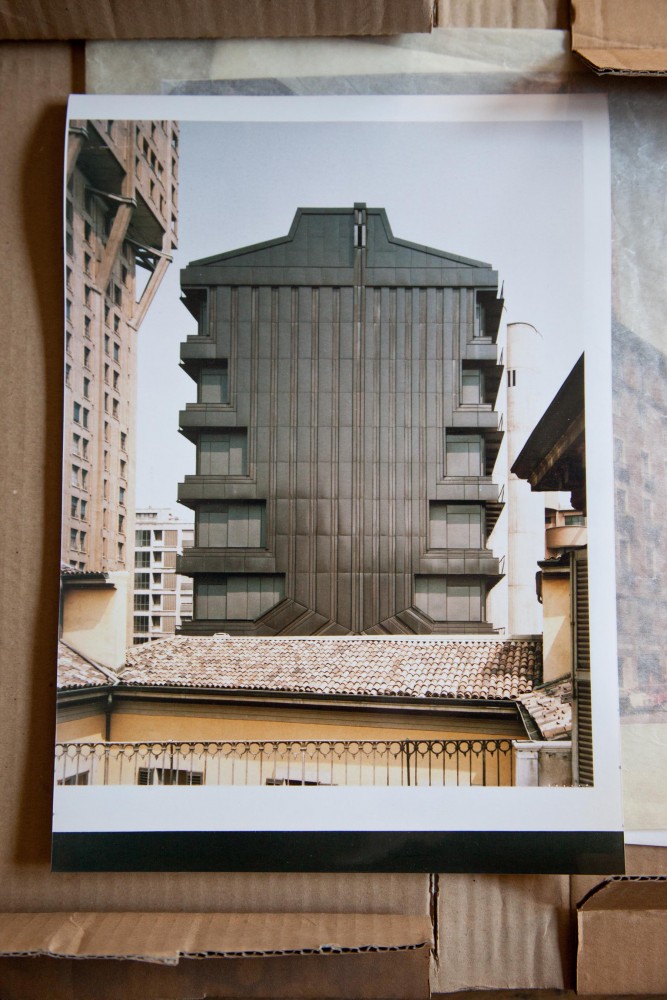

In fact, the multiple trajectories of postwar Italian architecture and design, particularly in Milan, would be inconceivable without Caccia. Present on almost every corner of his native city, Caccia’s architecture subtly alters the urban texture. It is no exaggeration to say that Caccia’s architecture is hidden in plain sight, and yet Caccia was never interested in “blending in.” Close scrutiny reveals that he was especially skillful at making the pre-existing urban fabric seem to adjust to his interventions, rather than the other way around. And though one can plausibly argue that all important urban architecture participates in this kind of gestalt switch, few in Milan have pulled it off with such a heady mixture of grace, precocity, and aristocratic discretion as Caccia himself.

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni’s family home (1947–50) on Piazza S. Ambrogio: “A closely knit ensemble of vertical and horizontal articulations” © Giovanni Chiaramonte

-

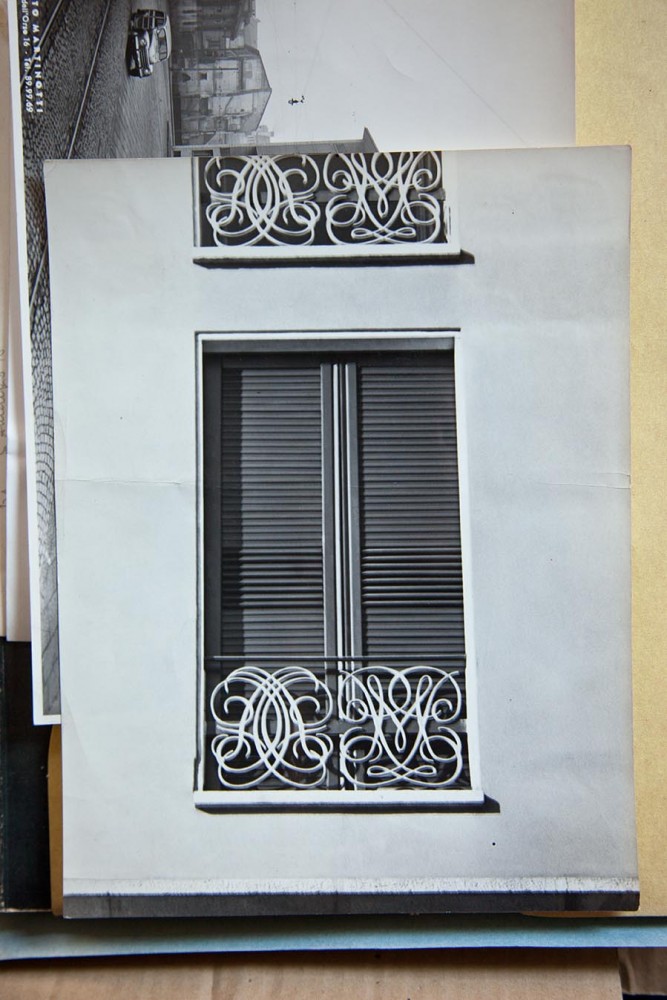

The balconies on the Caccia Dominioni’s family home on Piazza S. Ambrogio (1947–50): “Interwoven initials signifying the two sides of his family, the Paravicini and the Caccia Dominioni, abstracted to the point of constituting a kind of modern Baroque” © Caccia Dominioni Archives

Despite, or perhaps precisely because of its subtlety, the “Caccia effect” becomes readily discernible only when one knows how and where to look for it. Often it is invoked in prominent sites but without the original sureness of touch. When, for example, Antonio Citterio designed the Bulgari Hotel a stone’s throw from the Parco Sempione in 2004, he relied on Caccia’s language as his privileged model, even if he handled the design instruments of the older architect with far less skill and a self-consciousness that is the true mark of the derivative. A more significant contemporary figure who draws freely on Caccia’s example, conjugated with formal and spatial motifs taken from a number of inspirations including the work of Steven Holl, is arguably one of the most important young architects in Italy today, Cino Zucchi. These and many other instances show that the “Caccia effect” is a pervasive though insufficiently analyzed phenomenon, suggesting that his reach is greater than one might initially have suspected for such a rarefied figure. Even in “SuperDutch” territory Caccia has left his mark: MVRDV’s Balancing Barn (Sussex, England, 2010) is clearly indebted to the Italian architect, no matter how hard it tries to cover its tracks. For though there can be little doubt that the Dutch firm has borrowed the basic cantilevered volume from Caccia’s Fabbrica Loro Parisini of 1951–57, the pushing and pulling to which the model has been subjected conveys a will simultaneously to subsume and suppress the originality, and perhaps even the priority, of Caccia’s precedent. All of which goes to show that those in the know are aware that Caccia was the man behind the throne, and, moreover, that he probably designed it as well.

The former Loro Parisini factory (1951–57) in Milan’s Tortona district: “Little doubt that the Dutch firm MVRDV has borrowed the basic cantelevered volume for its Balancing Barn in Sussex” © Caccia Dominioni Archives

From these few examples, some general hypotheses can be inferred. Chief among these is that comparing Caccia to his epigones makes his self-assured discretion stand out all the more, particularly when seen alongside the brashness, hype, and self-promotion that surrounds much contemporary practice. This comes as no surprise since if any one figure may be said to epitomize the values of the Milanese aristocracy, it was Caccia: combining the broad scope of cultural memory with an instinctive formal restraint, his work offers a meticulous synthesis of historical awareness and imaginative audacity. As a result, it has few contemporary parallels. Caccia’s Janus-like stance, transforming the remembrance of things past into a skeleton key able to open the doors of the future, stands out with greater clarity than the timeless embrace of typological anonymity à la Aldo Rossi. This duality of prospective and retrospective tendencies explains why, perhaps more than any other protagonist of his generation, Caccia answered a specific need that was characteristic of a postwar era shaped by the radical changes of modernization: to reconcile the technological advances of industrial development with a will to historical continuity. Moreover, that this will did not succumb to nostalgia, but undertook an active exploration of the sources of cultural memory with the aim of making them available to the present, says everything about the specificity of Caccia’s contribution, which, in addition to resisting facile stylistic classifications, defies any reductive reading of its historical role.

-

A convent in the Swiss town of Poschiavo features Caccia’s typical curvilinear plans and elaborate stone flooring: “Combining the broad scope of cultural memory with an instinctive formal restraint” © Vincenzo Martegani

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Convent in Poschiavo, Switzerland (1968) © Vincenzo Martegani

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Convent in Poschiavo, Switzerland (1968) © Vincenzo Martegani

-

Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Convent in Poschiavo, Switzerland (1968) © Vincenzo Martegani

Caccia’s versatility in this respect — uniting a unique sensitivity to the historically developed languages of form with an openness to new approaches — was matched by that of his old friend, the presiding genius of Milanese architecture and design, Giò Ponti. Ponti did much to promote the young Caccia in the pages of Domus, the journal he founded. Ponti knew a good (or great) thing when he saw it, and he knew, as well as anybody else and probably far better, that Azucena, the design firm established by Caccia and his close collaborator Ignazio Gardella in 1947 (along with Corrado Corradi dell’Acqua and Maria Teresa and Franca Tosi), was destined early on to become a beacon of international, and not only Italian, design. Ponti’s prophecy proved to be prescient, and after a gradual rise to a period of discreet primacy in Milanese and Italian design and architecture, it is now becoming clear to a younger generation that Azucena’s potent synthesis of continuity and invention is exactly what is needed in a world weary of dated Postmodern caricatures and the equally sterile repetition of exhausted Modernist tropes.

Radio Phonola 547, designed by Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Livio and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni (1940)

Certainly, there is nothing dated or repetitive about Caccia’s endless inventiveness, and his mind and hand are as fertile now as in 1936 when he opened his studio after graduating from the Politecnico di Milano. There he studied with Luigi Moretti (from whom he arguably derived an aspect of his profound spatial understanding) and Piero Portaluppi (who taught him a crucial lesson: follow one’s own path, no matter where it leads, even if it results in the most singular of exceptions). One of the earliest works to bring him fame was the iconic Radio Phonola 547, designed in collaboration with Livio and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni (older brothers of the more well-known Achille) on the occasion of the VII Triennale in Milan in 1940. Combining a novel technical solution, a strong chromatic statement, and rounded contours modeled in Bakelite, the Phonola 547 set a new standard for modern radio design in its clear insistence on the compactness of the object.

Caccia Dominioni’s Sasso lamp for Azucena, 1948: “Effectively uniting natural and industrial elements at an intimate domestic scale” © Azucena Archives

The same inflection of an easily recognizable typological image through a unique fusion of industrial production and refined craftsmanship, in this case, responsive to ideas originating in the artistic avant-gardes, is evident in one of Caccia’s seminal works, the Sasso lamp of 1948. Integrating the organic form of a natural objet trouvé (a base made out of a polished river pebble) with the compact tectonic expression of the brass supporting rod and black enameled-metal reflector, the Sasso effectively unites natural and industrial elements at an intimate domestic scale. Since the metal reflector was taken directly from an actual Singer sewing-machine lamp, the pebble is not the only found element of the ensemble. Today Sasso lamps are extremely rare, and were originally demonstration and/or presentation pieces, symbols of the inventive spirit of Azucena itself — a fact which only enhances their aura as distinctive one-offs that take the form of highly crafted multiples instead of objects of design in the conventional sense. One measure of the Sasso’s success as the emblem of a novel aesthetic is that it sent the young Achille Castiglioni on his quest for a new mode of experimental design based on the ingenious reuse of found objects, as in the Toio lamp (1962), a work whose incorporation of car headlights reveals, possibly for the first time in Italian design, the impact of the Duchampian readymade on the formal elaboration of objects of daily use. Yet what became explicit in this respect in Castiglioni was already emerging, albeit in a more recognizably naturalistic form, in Caccia: like Duchamp himself, Castiglioni took the idea of the modern found object to its logical conclusion, by making all of the components in the assemblage industrial.

The Bicolore bed, 1989: “Betraying more than one point of contact with the oneiric visions of Massimo Scolari, adding to the bed’s sybaritic charm à la Barbarella” © Azucena, Milano

Other significant contributions by Caccia in the postwar era include the Cavalletto table of 1949, whose tiny feet protrude at reversed angles in a detail whose subtlety is typical of Azucena; the Catilina armchair of 1957, whose three metal rods and flat, dark, curved metal strips, one of which twists to form an inflected backrest, combine Modernist purity with a neo-medieval sense of form; and the elegant Monachella reading lamp of 1953, which, with its attenuated diagonal profile paired with a “monk’s cowl” reflector, demonstrates a singular blend of historicizing reference and aerodynamic elegance. Subsequent works such as the Bicolore bed of 1989 register a more daring transformation of historical precedent, effected in this case by an attenuation of form and a flared symmetrical profile which lends a hieratic quality to the solution. This work betrays more than one point of contact with the oneiric visions and neo-Egyptian explorations of Massimo Scolari, an affinity that only adds to the bed’s sybaritic charm à la Barbarella. All the works discussed so far make clear Caccia’s agility in walking the tightrope between the understated and the dramatic. Freely utilizing a wide variety of historical precedents as a basis for his highly original poetics, his approach epitomizes the conversation between tradition and modernity that is a hallmark of Milanese Modernism, assimilating the multiple legacies of the past to free the imagination of the designer rather than hinder it.

Interior hallway of Corso Italia 22, Milan (1957-61). Floors by Francesco Somaini, sconces by Luigi Caccia Dominioni and Ignazio Gardella.

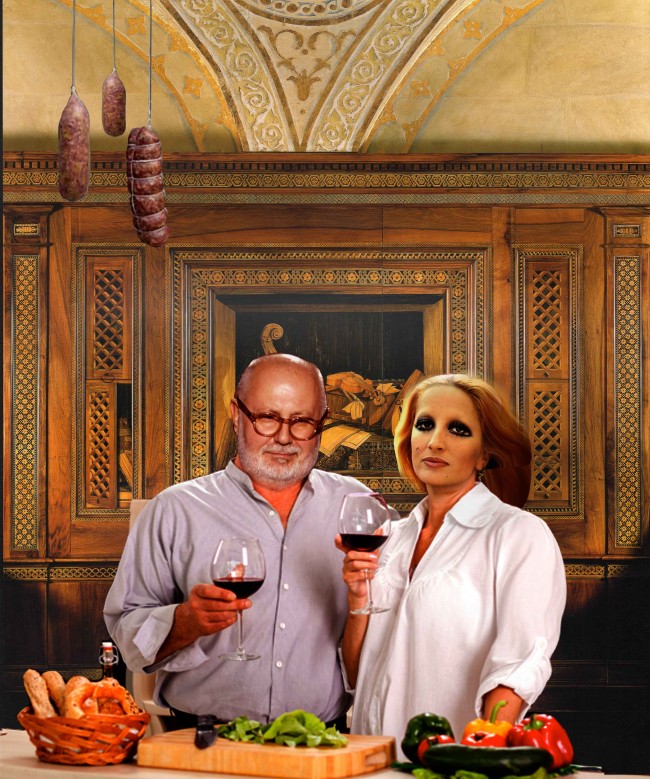

The attempt to evaluate the liberating function of history that runs through Caccia’s output raises many questions, and arguably the best person to answer them is the architect himself. I was lucky enough to be able to put some of these questions to him during a chance encounter back in 2006, which came about because of that aficionado of everything even remotely connected with Italian design and architecture, Brian Kish. That summer, Brian and I made an impromptu visit to Caccia’s palazzo in the heart of Milan, at Piazza Sant’Ambrogio 16, which the architect totally rebuilt after the Allied bombing of 1943. Without expecting it, we stood suddenly face to face with an impressive figure with finely chiseled features and a shock of white hair, impeccably dressed — a true aristocrat from head to toe, greeting us at the portal which was flanked by two bronze sculpted wolves.

-

Catilina Piccola chair for Azucena, 1962: “Modernist purity with a neo-medieval sense of form” © Azucena, Milano

-

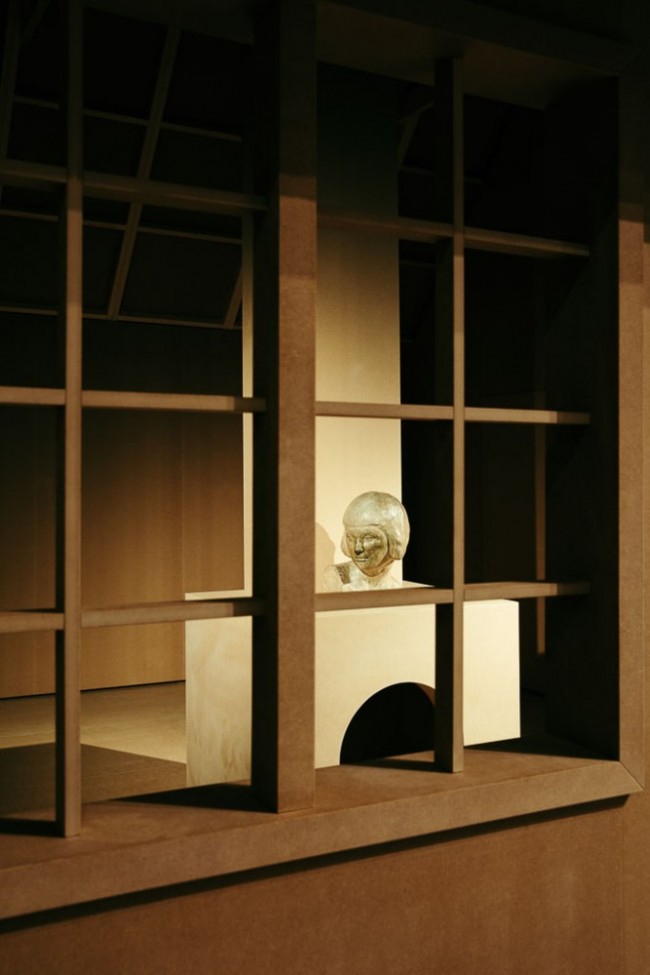

The collection by Luigi Caccia Dominioni by B&B Italia, 2018.

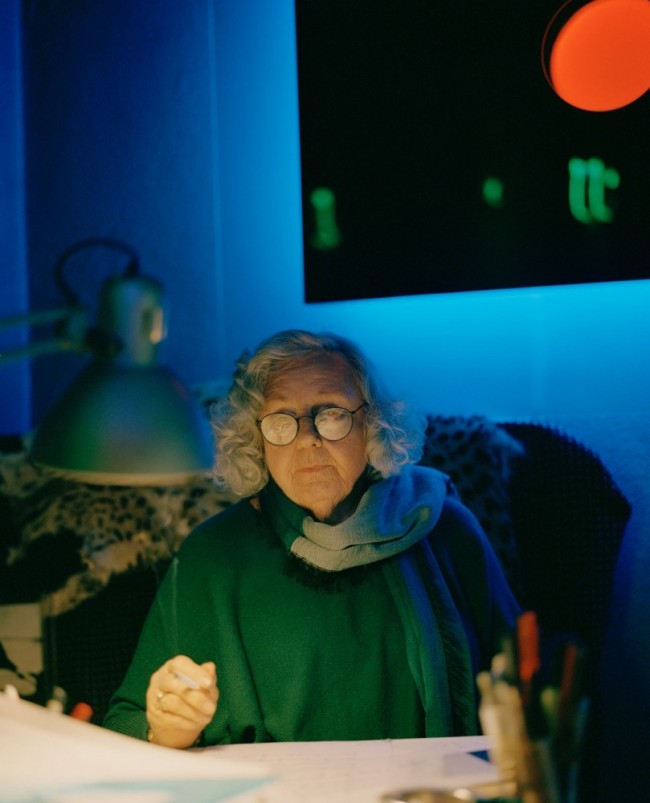

Once inside Caccia’s home, the first thing I noticed was the rich upholstery of the walls, in burgundy and black, against which were set burnished sconces, all of which contributed to an enveloping yet spacious atmosphere that was as dignified as it was somber. No sooner had I taken it all in that we were whisked down a spiral staircase straight into the architect’s spare and airy basement studio — a space both luminous and welcoming. Caccia took up his position at his desk, compass and pencil in hand, and gave us a spontaneous lezione di architettura. Hours passed in the twinkling of an eye as he filled reams of paper with curves and corridors. I can’t recall everything he said, but one thing in particular sticks in my memory: “The truth is, I’m a Baroque architect. Modern architecture began with the Baroque.” The unexpected sense of conviction implied by this observation from one of Milan’s greatest living architects made me think instantly of the young Borromini who, passing through Milan on his way to Rome, saw the first entirely curved façade in Western architecture, the Collegio Elvetico (c. 1610), by the otherwise obscure architect Francesco Maria Richini. (Interestingly enough, Borromini himself took his name not from any Roman source, but from the Counterreformation archbishop of Milan, Carlo Borromeo). We tend to think of the Baroque, in Italy at least, as being centered in Rome, yet the fact remains that if not for this stopover in Milan, the Roman Baroque would never have occurred, and all of subsequent architectural history, including the rise of Modernism which revolted, as did the Baroque, against rigid classical canons, would not have come about. So it makes sense that Caccia should see the Baroque both as somehow quintessentially modern and, by implication at least, quintessentially Milanese.

-

The lobby of the Teatro Filodrammatici in Milan, 1967: “The movement of the eye as it follows the shape of the curve and the movement of the subject as it traverses the multicolored mosaic floors” © Alessandro Zambianchi

-

Mosaic floors of the Teatro Filodrammatici, Milan (1967)

Such radical ideas about the relationship between history and modern architecture are quite comprehensible from a Milanese point of view. In addition to Richini’s Collegio, one cannot think of curves in Milan without remembering the swirling circular wall segments of Caccia’s work in the mid-1960s — as for instance in the Biblioteca Vanoni in Morbegno of 1965–66 — or the dynamic inlaid patterns of the multicolored mosaic floors, made of strips of marble tile in brown, black, white, and sepia, by his collaborator the sculptor in the Galleria Strasburgo (1957), or the equally dramatic swirling floor of the Teatro Filodrammatici (1967), whose spare yet dynamically curved corridors present certain affinities with the formal universe of Caccia’s teacher, Luigi Moretti. In addition to harnessing the energies contained within curved surfaces as a key to both formal and spatial movement — that is, the movement of the eye as it follows the shape of the curve and the movement of the subject as it traverses the space — both the Galleria Strasburgo and the Teatro Filodrammatici attest to the close relationship between theory and practice that pervades Caccia’s output. For it was he who made the following observation regarding the role of circulation (an insight that all has the force of a manifesto): “People tend to move in meandering lines; they don’t go back and forth in straight lines but move in circular, oval or meandering lines.” It is this sense of an endless meandering movement, translated into a dynamic language of form and space, that Caccia finds in the curvilinear idiom of his Baroque precursors, from which he extracts a deep understanding not only of the Baroque but of modern architecture as well.

Lateral façade of the Cartiere Binda office building in Milan, 1966: “Participating in the formal language of international Brutalism from a remarkably original angle” © Caccia Dominioni Archives

Another of his signature strategies is the singular approach to fenestration he invented and put into practice in a number of different projects, including many Milanese palazzi, where, to the casual observer, the disposition of the windows across the façade appears entirely arbitrary and random. What was behind it? I asked him. “Too often,” he replied, “designers overlook the basic fact that chairs and tables, along with the people that use them, do not exist in a void, but are involved, incessantly, in conversations. So I make sure that the windows cast light exactly on the interior design, which comprises the space as well as the furniture as I have arranged and envisioned it.” This is but just one instance of a defining characteristic of Caccia’s idiom, the dynamic unity of architecture and design, rooted in the rhythms of discourse and of life itself. Much of Caccia’s language is unprecedented and, for this reason, can be seen as intrinsically forward-looking, anticipating specific developments in the wider panorama of international Modernism. This power of anticipation is apparent above all in the relationship between the industrial side of Caccia’s approach and the trajectory of James Stirling, which he prefigures by over a decade. Indeed, the cantilevered volume, marked by a strong surface treatment that seems almost Brutalist in its hexagonal patterning, of the aforementioned Fabbrica Loro Parisini (which predates the work of Stirling that is closest to it in spirit, the Leicester Engineering Building of 1959–63), is remarkable for its prescience; one should also mention the Cartiere Binda of 1966 which participates in the formal language of international Brutalism from a remarkably original angle. Again it seems that Caccia helped set into motion codes and languages that his own work would subsequently react to, given both the unusually long span of his career and the remarkable fertility of his ideas.

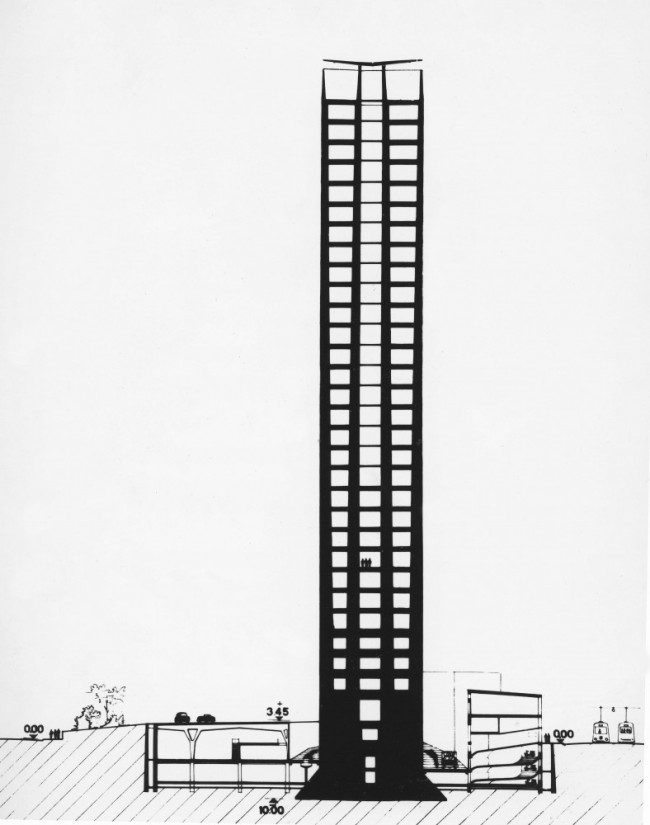

The famous residential tower on Milan’s Piazza Carbonari, 1960–61: “The position of each window is cannily adjusted to the placement of the furniture within” © Giorgio Casali/Domus

The residential tower on Milan’s Piazza Carbonari (1960–61), one of Caccia’s most famous works, should also be read in this context, as it simultaneously participates in the current of international Brutalism while instigating a “semantic distortion” of the traditional Milanese residential typology that is entirely specific to Caccia. His continuous engagement of the conversation between design and architecture is evident above all in this building whose burgundy-colored skin of bricks and staggered roof profile stand out within his output as a compelling instance of perceptual and spatial dissonance. A certain abstract pictorial quality is imported to the tower’s façade by the seemingly random fenestration, an impression that is reinforced by the occasional black window panel in dark opaline glass; but in fact, the position of each window is cannily adjusted to the placement of the Azucena-designed furniture within. Caccia’s comprehensive, total approach, bringing together furniture design, typological experiment, and a new awareness of the urban determinants of the intervention, coordinates every element at all scales. With regard to the Milanese palazzo typology, Caccia transforms it in two important ways: first, by working from the inside out, taking the placement of the furniture he designed as an essential part of the equation, and second, by conceiving the project in terms of the received typological language of the canted roof, which buckles and deforms as if it were the superimposition of several different roofs of distinct urban palazzi telescoped into one. In this way, codes of unity and multiplicity are scrambled and recombined at every scale, producing a distinct Entfremdungseffekt or “making strange” of the residential type that participates in the formal apotheosis of this work.

-

Exterior of Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Interior of the salon in Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965): “Seeing the Baroque both as somehow quintessentially modern and, by implication at least, quintessentially Milanese” Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Interior of the salon in Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Dining room at Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Dining room at Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

View of the garden from the salon in Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Interior of the salon in Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Interior of Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

-

Interior of Casa Pirelli, Milan (1965). Photograph by Valentina Angeloni.

Let us end our (highly selective) overview of Caccia’s oeuvre by returning to the architect’s most personal work: his own home on the Piazza Sant’Ambrogio. In our interview with him, Caccia points to this house — his first architectural realization — as an instance of how he responds to the pre-existing urban fabric. To our question whether he built literally on the ruins of the palace destroyed by the Allied bombing of August 1943, he responded with the inner composure of a man who knows the history of his native city in his bones but for that very reason is not afraid to innovate — with great respect for that very history. Here it is important to remember that what Caccia calls the “calm rhythm” ritmo pacato of the neighboring early-Christian church of Sant’Ambrogio inspired him to create the serene composition of the façade, without falling into any extreme of populism, Neoclassicism, or Modernism — on the contrary, he masterfully triangulates all three idioms, as Anna Chiara Cimoli (one of the more insightful writers on Caccia) has pointed out. Caccia’s façade comprises a closely knit ensemble of vertical and horizontal articulations whose rhythm is inspired by that of the adjacent church; dividing the palace into well-defined areas of visual interest, these articulations create a unified configuration of five superimposed floors whose planes recede and step forward at regular intervals, a formal strategy that generates an interplay of open spaces, unadorned colonettes, and the floating plane of the piano nobile, whose rectangular windows could not be more austere and direct. The latter include balconies which allow a view connecting the interior and the exterior, thereby integrating the palace with one of the oldest urban spaces in the heart of Milan. In addition to creating a subtle juncture between architecture and the city, Caccia’s balconies envision a new role for architectural ornament, abstracted to the point of constituting a kind of modern Baroque. The interwoven initials in the wrought-iron work signifying the two sides of his family, the Paravicini and the Caccia Dominioni. Hidden in plain view, these discreet signs are typical of the refined craftsmanship that characterizes Caccia’s architecture and design. Yet, with quiet self-assurance, they also address the entire piazza, and by extension the urban space as a whole. As a result, they are emblematic of the singular unity of formal innovation and historical awareness that Caccia brings to this and to all of his subsequent projects. This felicitous conjunction runs through the whole of Caccia’s output and is a major factor in its cultural orientation, registering the fact that Milanese architecture has always followed a specific direction able to reconcile distinct, yet not necessarily opposed, currents of modernity and tradition. Ultimately Caccia’s world offers a vision of unity that other design cultures, such as that of the USA today, seem increasingly unable to achieve.

Portrait of Luigi Caccia Dominioni sitting in his Catilina chair. Photograph by Agostino Osio.

Text by Daniel Sherer.

Taken from PIN–UP 16 Spring Summer 2014.