GIO PONTI: 15 Picks From The Prolific Italian Designer’s Archive

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

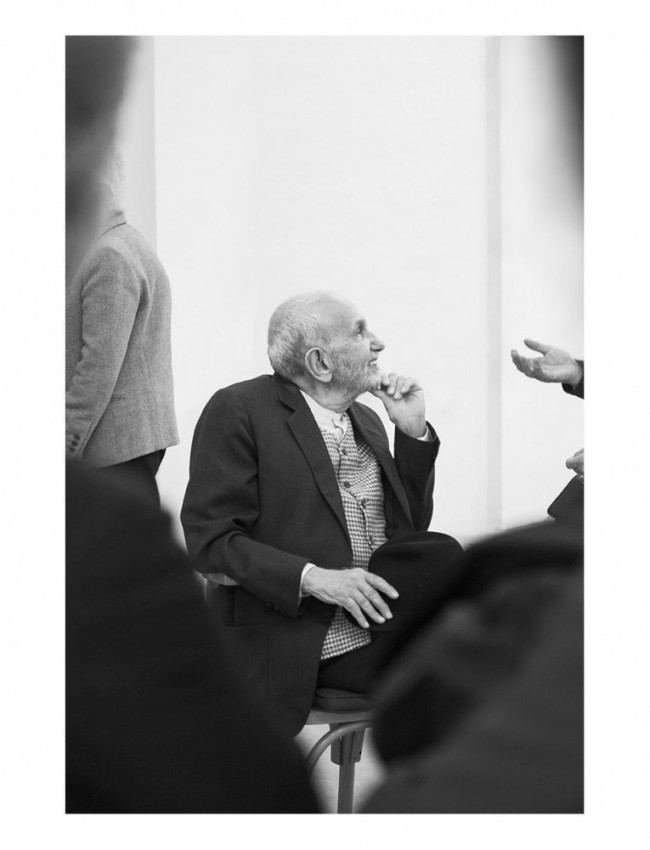

No one in the past 100 years has influenced Italian architecture and design more than Giovanni “Gio” Ponti. Between the 1920s and his death in 1979, this thoroughbred milanese left his creative fingerprints on every aspect of Italy’s design scene: furniture, home accessories, textiles, interior design, exhibition scenography, and of course architecture. Ponti produced at a frenzied pace, often collaborating with other creators and nurturing the careers of new talent who would become household names themselves. In 1928 he co-founded the architecture magazine Domus, ensuring that his legacy would persist far into the 21st century. “I first visited Milan as a teenager, and I remember seeing Ponti’s Pirelli tower for the first time and thinking how elegant it was,” says Karl Kolbitz, the editor and designer of Taschen’s comprehensive new book, titled simply Gio Ponti. Kolbitz grew up in 80s and 90s East Berlin amid a Cold War grittiness that couldn’t be further from the pastel-colored bourgeois fancy Ponti is best remembered for. It is Ponti’s versatility that he can most relate to: “He was able to work with any material, effortlessly moving from micro to macro scale within a single project.” If Ponti is the holy grail of 20th-century Milanese design, Kolbitz earned the stripes to do the book through another title he produced for Taschen in 2017, Entryways of Milan, which documented the splendor and inventiveness of hundreds of Milanese lobbies, foyers, vestibules, and semi-public hallways in a city that is otherwise known to be physically and socially hermetic. The Milanese are notoriously hard to please, but with Entryways Kolbitz cracked the code, opening doors that would have otherwise remained closed, including those of the Ponti family. Produced in direct collaboration with the heirs — Ponti’s grandson Salvatore Licitra curated the book and contributed texts — Kolbitz’s giant 572-page tome teases out the variety, inventiveness, and sheer volume of Ponti’s oeuvre. “Ponti was always searching for lightness, so it’s ironic that the book ended up being quite heavy,” deadpans Kolbitz. Twelve pounds, to be exact, packed with over 1,000 illustrations and photographs. Exclusively for PIN–UP, the editor picked some of his favorite Ponti projects.

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

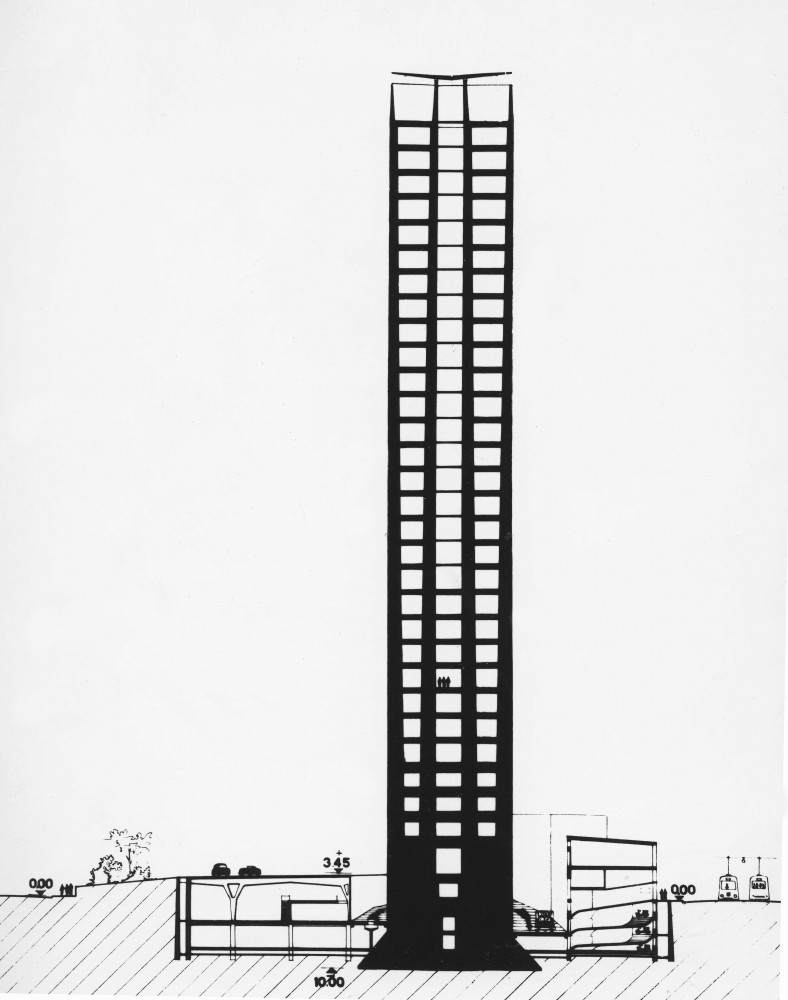

Pirelli Tower, Milan (1956–58)

“The Pirelli Tower is one of Ponti’s masterpieces. The real beauty lies inside, where Ponti combined two of his leitmotifs. Firstly, the floorplan is in the shape of a crystal or a diamond, which Ponti considered the perfect shape. Secondly, Ponti was on a lifelong search for ‘finite form’ — something that cannot be altered. Here he achieved it by tapering the building’s piers towards the top, hence structurally preventing any additions.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

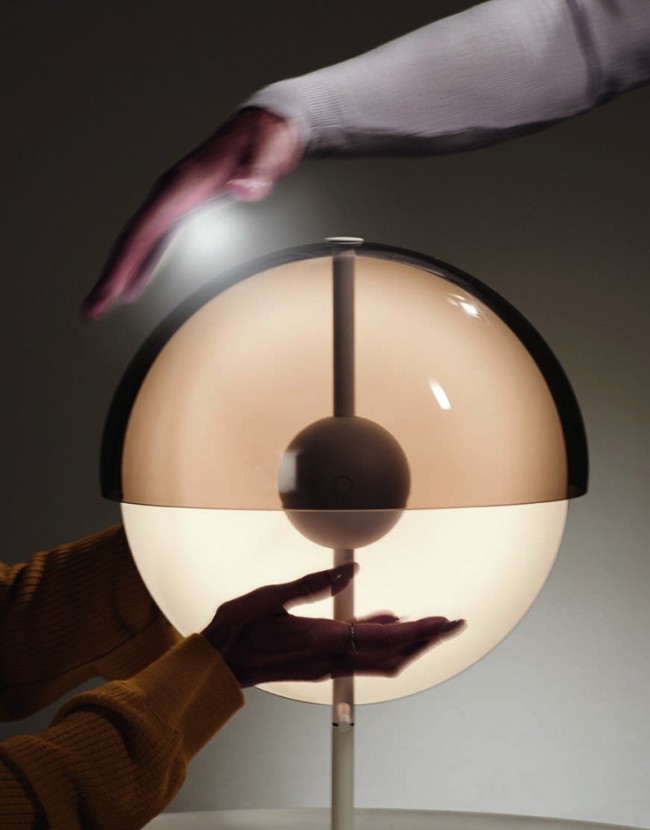

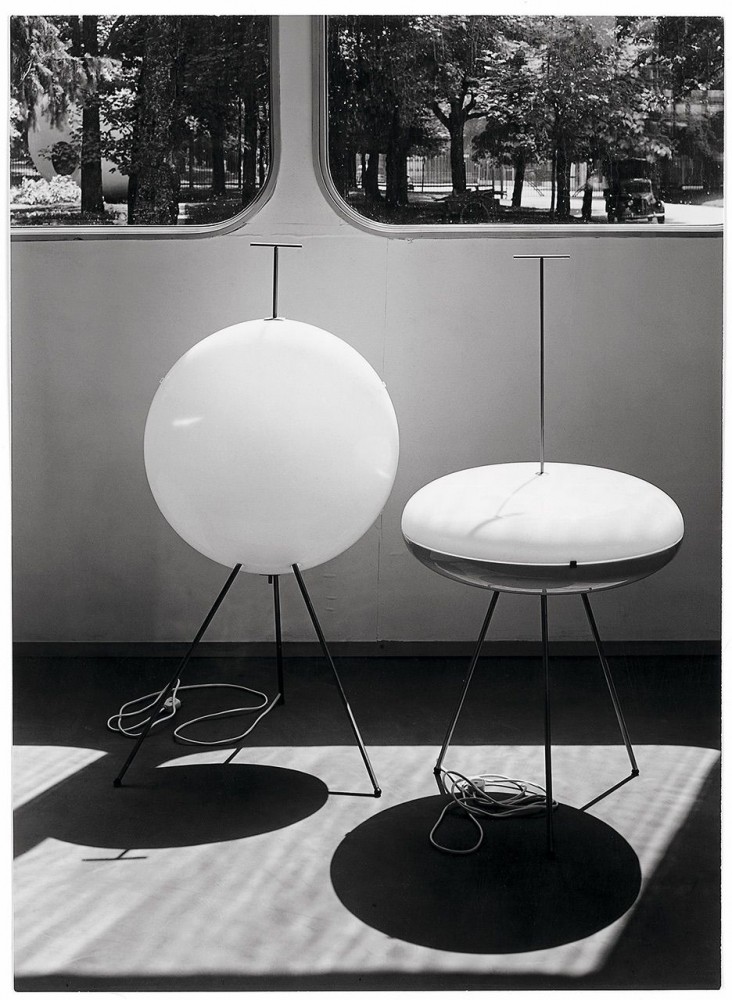

Prototypes for lamps (1957)

“I like these prototypes from the mid-50s because the shapes are unusual in Ponti’s oeuvre. The lampshades are made from Plexiglass while the structure is in brass. The little handle on top is a nice touch that allowed the lights to be mobile — Ponti liked everything to be light and dynamic. Unfortunately, they never went into production.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Villa Planchart Caracas (1953–57)

One of Ponti’s masterpieces, a Gesamtkunstwerk where he designed the structure and everything inside from floor to ceiling. Literally, including the plates on the tables. Some photos of the interiors are absolutely iconic. However, I love this exterior view that shows the internal lighting running behind the projecting (seemingly detached) façades planes. Ponti wrote “No walls to enclose the spaces, but walls that playfully outline the spaces.” I think this image makes the point clear.

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Freestanding oil painting of a reclining nude (1957)

“Ponti originally wanted to be a painter, but his father made him attend architecture school instead. Far from suppressing his talent it opened it up — he applied his artistic mind to everything he did. This oil painting of a female nude is another example for Ponti’s fascination with crystal shapes. Note the ingenious freestanding frame, supported by a simple metal rod.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Cono door handles (1956–57)

“Ponti always sought to reduce material as much as possible. His goal was to achieve an effect of lightness. These door handles, tapered towards the tip, are a great example of this never-ending pursuit, as are the 1957 Superleggera chairs, still produced today by Cassina. Ironically, the book we did ended up being quite a heavy tome, but that was unavoidable with an extremely vast body of work like Ponti’s.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

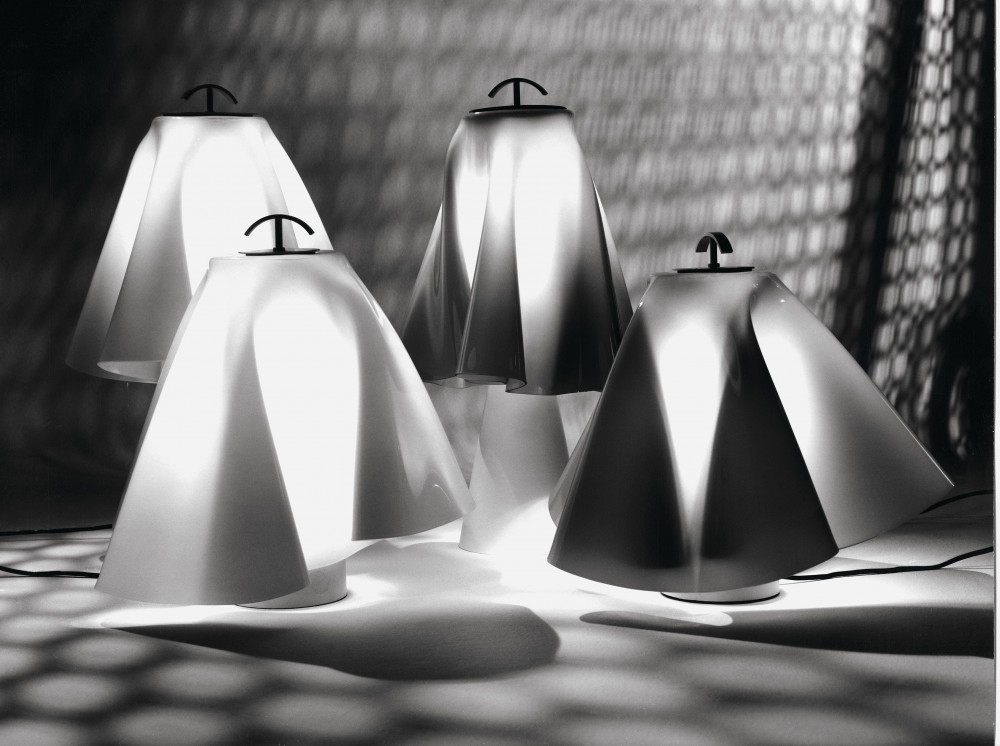

Cartocci lights (1967)

“Ponti took on the role of artistic director at FontanaArte in 1931. Over the years he was involved with the company, he designed many small and large glass pieces, from paper weights to tables and even windows, not all of which went into production. Case in point, these glass and nickel-plated table lamps. I think it’s amusing that the glass looks so floaty and light, like little dancing ghosts.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Glass-and-marble coffee table (1948)

“This coffee table was a private commission for one of the many apartments Ponti was working on. I really like the way he framed the marble slab, embedding it within the table’s structure so as to show off its natural beauty.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Tall display case (1950)

“In addition to his obsession with crystals, Ponti also loved obelisks. To him the obelisk was the true and pure symbol of architecture, and tapering forms can be found in many of his works. This residential display case represents Ponti’s transitional period from a Neoclassical to a more streamlined Modernist expression.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

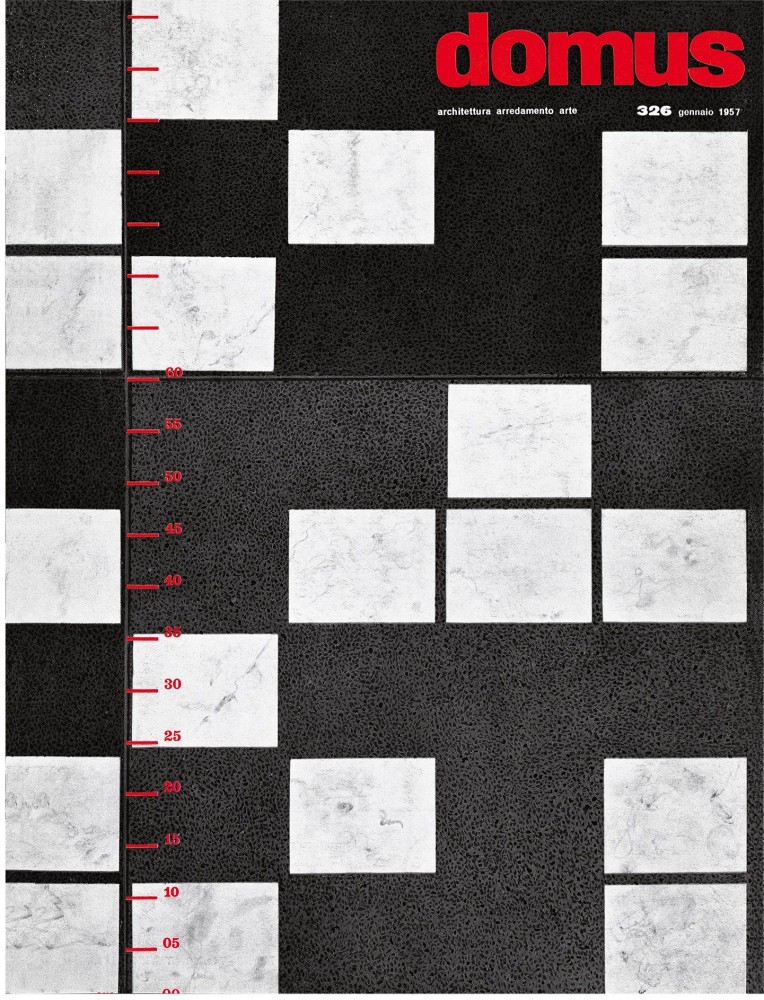

Domus magazine (1928–79)

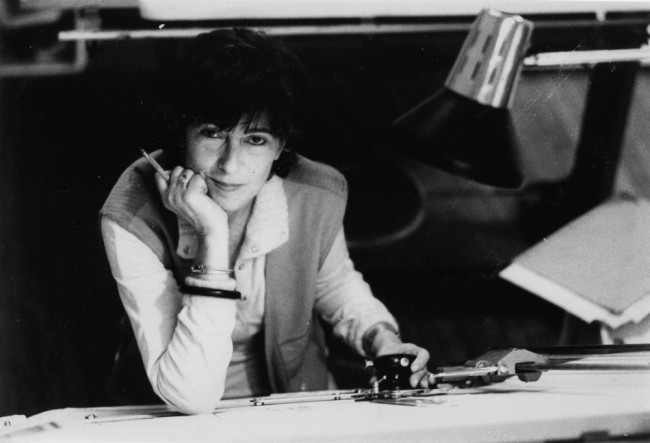

“Perhaps Ponti’s biggest contribution to culture was the 1928 founding of Domus magazine, of which he was editor off-and-on until his death in 1979. Domus functioned as a cultural catalyst and was an important platform not just for Ponti’s own work but for Italian architecture and design in general. Ponti was great collaborator, and he involved many other architects, artists, and designers in his projects, including Cini Boeri and Nanda Vigo. On the cover of this issue from 1957 is a geometric floor design by Ponti in marble and black cement.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

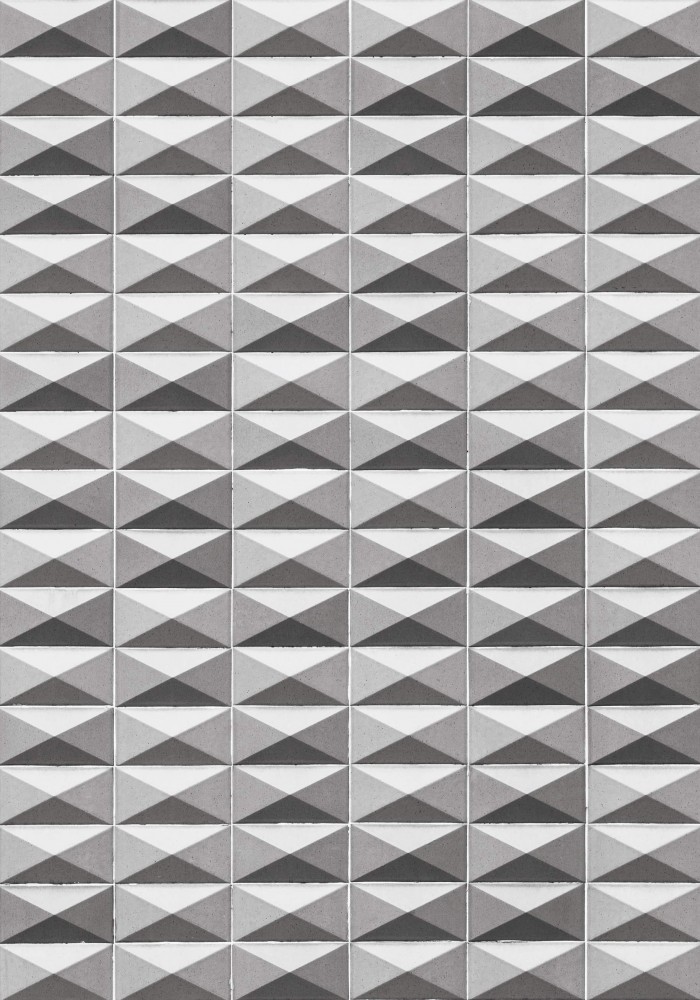

Tiles (1960s)

“Our book dedicates an entire chapter to Ponti’s ceramic tiles. This design is once again a nod to Ponti’s love for crystals. Ceramics were popular in Italy after the war because they were perceived as a democratic material available to all. Ponti tiled a lot of his façades, especially the religious buildings he designed in Milan, creating a beautiful shimmering effect. Many of his tile designs were used by other architects too, so sometimes a house or an entrance in Milan is mistaken for a Ponti design, when in fact only the tiles are his.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

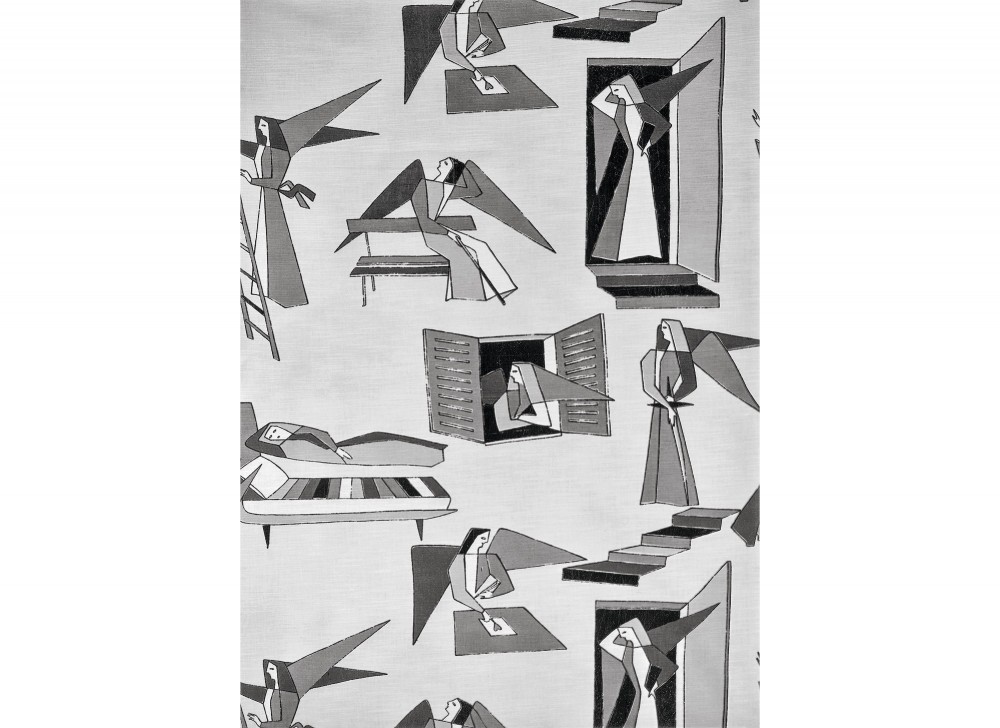

Gli angeli textile print (1950)

“Ponti also designed numerous fabric prints. He was deeply religious, and angels were a favorite and recurring motif in his work. Some of those in this print are really cute, such as the sassy angel standing in a door frame, the angel writing a love letter, the one hanging out on a park bench, or the sleeping angel, hovering over the daybed.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

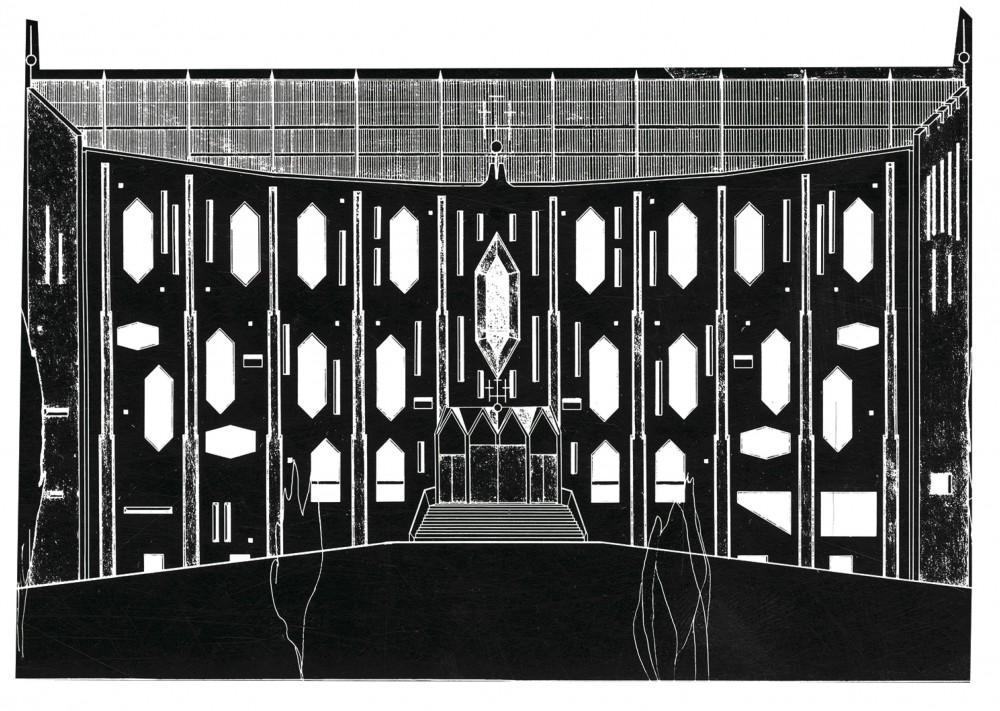

Church of San Carlo Borromeo, Milan (1964–69)

“Not only did Ponti build many office buildings — which one could see as temples of commerce — he also produced a lot of work for the Catholic church. One of his lesser-known churches is this one at the San Carlo Hospital in Milan. Not only is the floorplan in the shape of an elongated crystal, but so are all the big apertures and windows.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Round D.154.5 armchair (1954–57)

“Ponti designed this armchair in the mid 1950s, and it can be found in several of his most iconic projects, such as his two most famous villas in Caracas, Venezuela. Ponti also made versions of it as sofas and long benches for the Alitalia Airport Terminal in Milan, which he designed in 1960. Originally upholstered in innovative VIPLA, a type of vinyl, the chair was first presented to the general public at the eleventh Triennale di Milano in 1957. This year Molteni&C is bringing the Round D.154.5 back into production.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

Ceramic hands for Richard Ginori, 1935

“These are two designs that Ponti made for Richard Ginori, the ceramics company of which he was the creative director from 1923–33 — his first big gig. Similar versions are still produced by the company today, which is now called Ginori 1735. Ponti was obsessed with hands — they appeared everywhere, in drawings, letters, and lamps, and later on in life he even made hands with six fingers.”

© Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta)

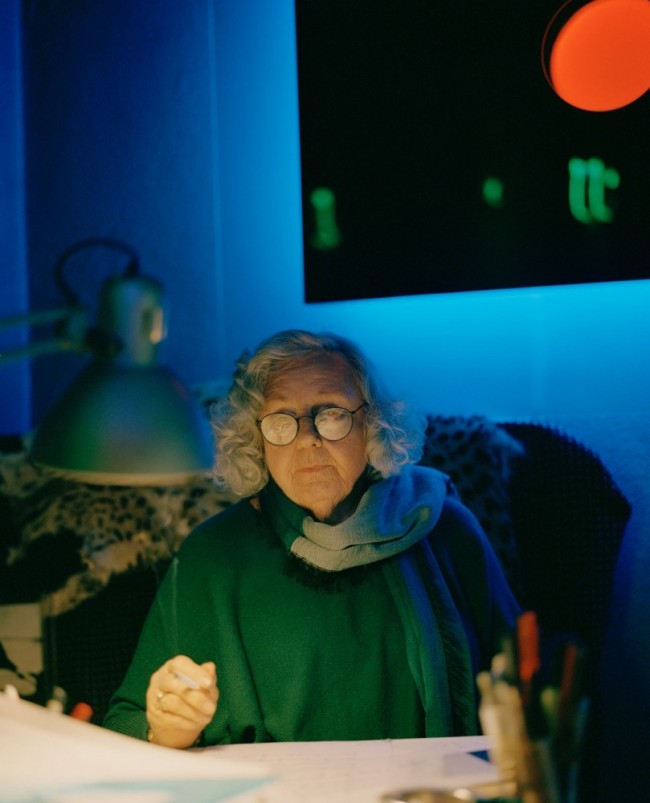

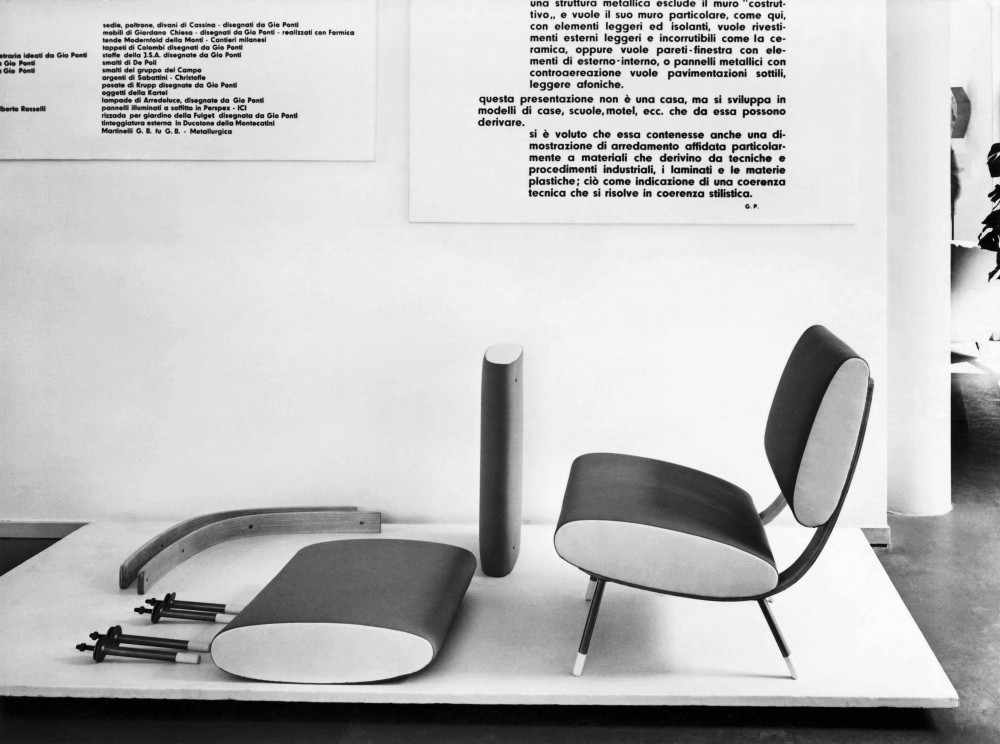

Exhibition at the Villa Olmo, Como, 1957

“During his lifetime Ponti curated a number of exhibitions of his own work. In typical Pontian manner, he defied categories and mixed different genres together, even including pieces by other artists and designers. Far from taking himself too seriously, he always added humorous touches, like placing a design for a toilet next to an armchair.”

Text by Karl Kolbitz.

Introduction by Felix Burrichter.

Images © Gio Ponti Archives/Historical Archive of Ponti’s Heirs. (Giorgio Casali) (Porta).