The Wallet Interview: Elise By Olsen in Conversation with OMA’s Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli

-

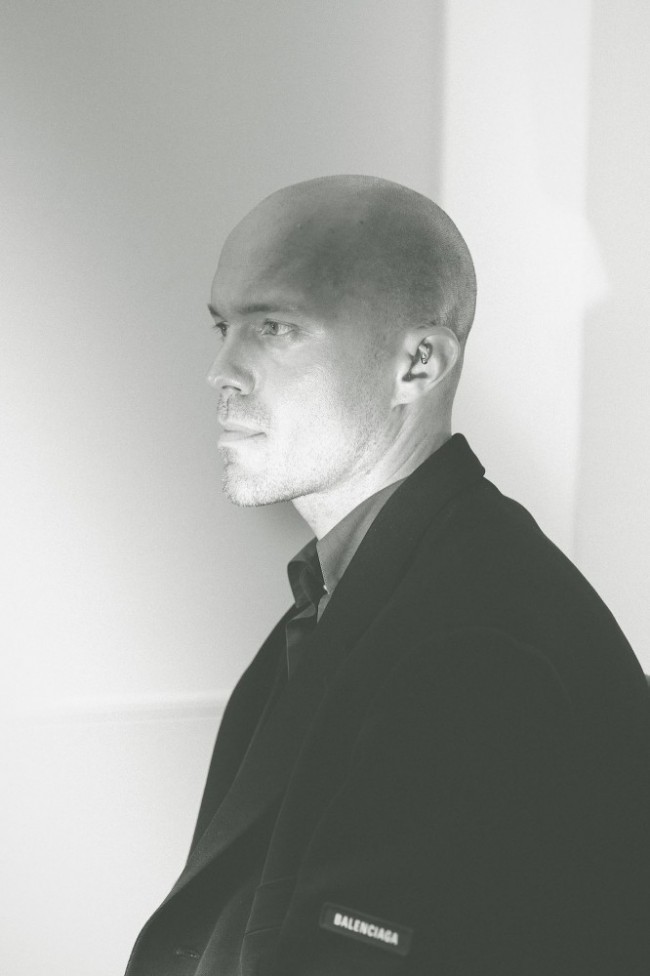

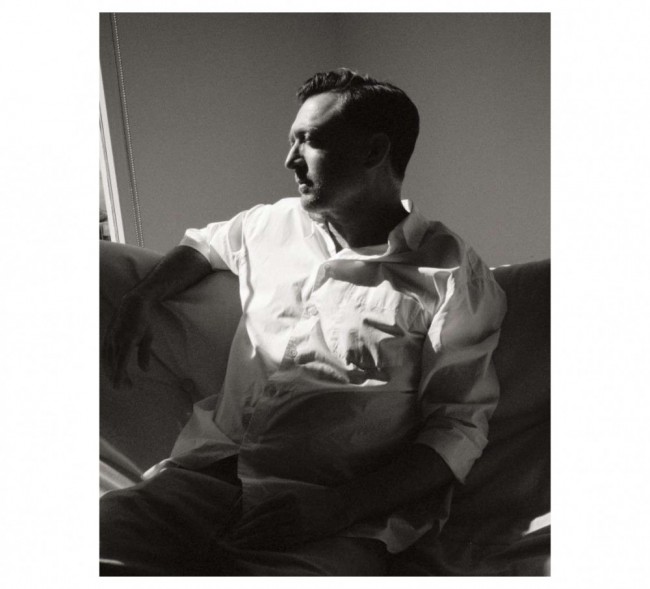

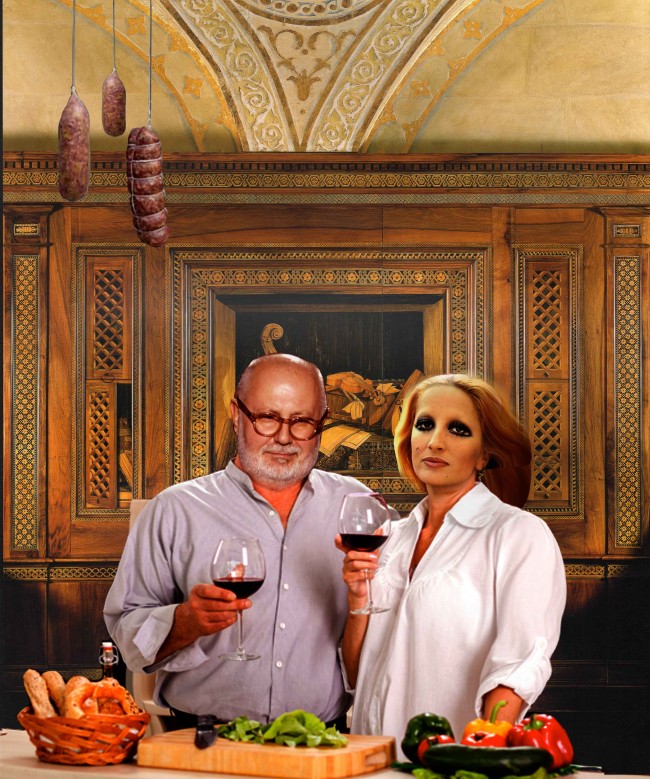

Architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli photographed by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm for PIN–UP.

-

Architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli photographed by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm for PIN–UP.

The latest issue of Wallet, the thinking person’s favorite pocket-sized fashion zine, is out! For its fourth print edition Elise By Olsen, Wallet’s editor and publisher, chose the subject of space. One of the “shamans of space” the 19-year-old interviewed for the issue is the Italian architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, a partner in the Rotterdam-based Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Pestellini Laparelli has worked on a number of projects for multiple fashion brands, including Prada, Repossi, Galeries Lafayette, and Kaufhaus des Westens (KaDeWe). He also co-curated the international biennial Manifesta in 2018 and holds a Master of Architecture from the Politecnico di Milano, and teaches at the Royal College of Arts in London and at TU Delft in the Netherlands. PIN–UP is exclusively publishing the full conversation between By Olsen and Pestellini Laparelli below. For the full issue of Wallet (featuring many more interviews with Grace Wales Bonner, Yohji Yamamoto and others) order your copy here.

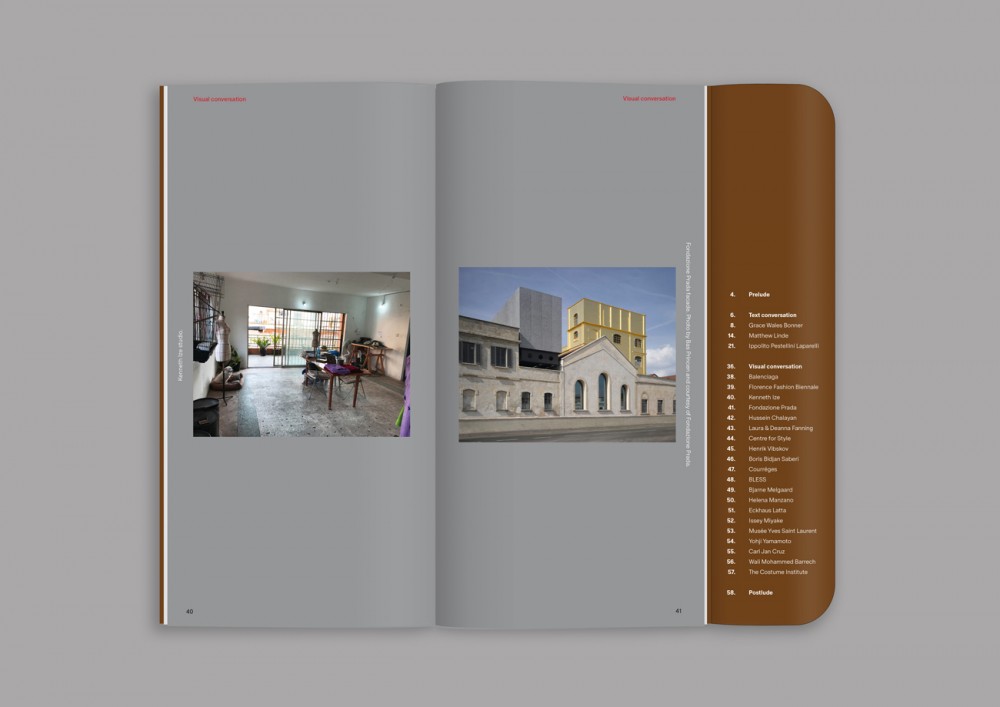

Views of Wallet magazine No. 4, “Shamans of Space.” Available now.

First, in the most general terms, how would you distinguish the different “spaces” of fashion?

I tend to not make any real distinction between the different spaces. In a way, designing a space is about scripting a story; it’s almost like walking through a movie. That can be applied to fashion, but also to other domains, from scientific buildings to cultural experiences and events. I know that people perceive fashion to normally require a certain degree of specificity, so a space dedicated to fashion must provide a certain kind of experiences, and so on. But my point is that the process of making a fashion space is not different from other domains.

Well, if we are not to focus on the difference, then how would you describe the relationship between architecture and fashion?

It might be more about process than form. What I learn from fashion is to be faster, and to deal with constructing a narrative that is much more agile than in architecture. Architecture in general is a very slow business; architects are known to be slow, to be careful and to wait for the time to come. What is very beautiful about fashion is that there is this brutally efficient creativity, something that we’ve tried to incorporate into our process. So while we are architects, we operate with the rhythm of the fashion business; taking things here and there and being able to make collisions between them, and collage them very quickly according to storylines or scripts that are simple and easy to communicate. This is something that we learned from fashion. Architecture can stage fashion and the process of making of fashion by providing a theatrical experience.

How did you get involved in fashion? And what was your first fashion project?

I got involved in 2007. When I started to work at AMO (OMA’s research and design studio) at our office in Rotterdam, my first assignment was actually to design a fashion show for Miu Miu in Paris. I was never exposed to fashion before, or at least not so directly. I was trained as an architect, but before joining OMA I used to work for a multimedia office, working with people doing videos and clips for very different clients, from media outlets to architects. Somehow that helped me to think beyond the traditional boundaries of architecture, and bring a cinematic experience to the fashion shows. But it all really started 12 years ago, from the one single set-up in Paris for Miu Miu.

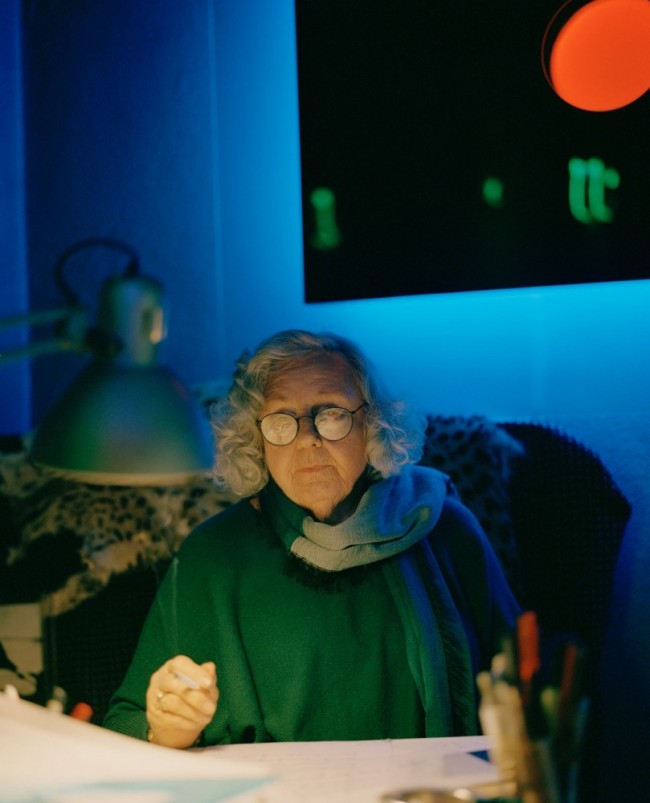

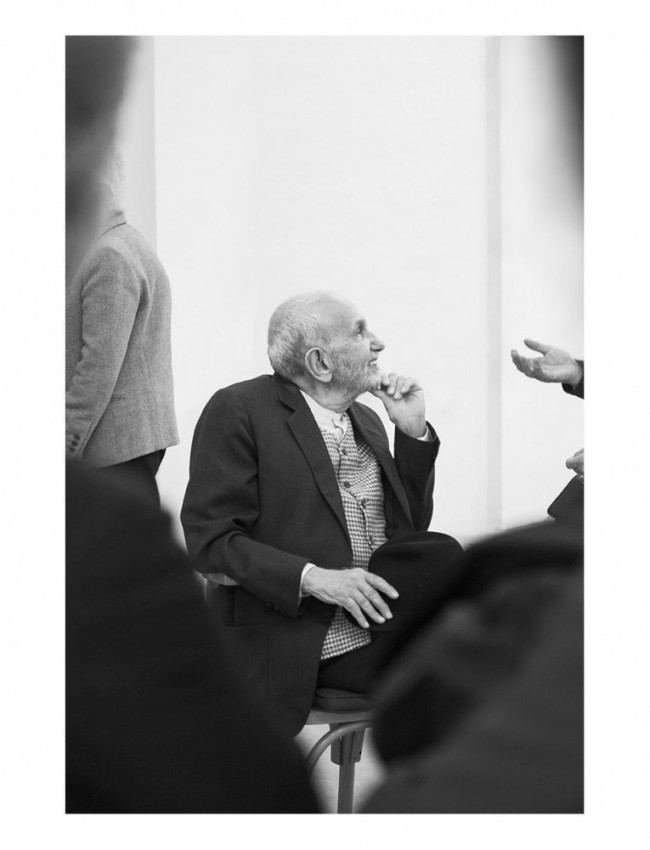

Elise By Olsen, founder and editor of Wallet magazine. Portrait by Peter Jordanov.

In fashion circles, you are most known for your work with Prada. When did OMA’s collaboration with Prada first start?

That’s already over 20 years ago. At the time, it was not common for architects to engage with the fashion business, that is something that came in the past 20 years. I think it started from a very personal connection and an encounter between Miuccia Prada and Rem Koolhaas. Mrs. Prada wanted to work with an architect on Prada’s new stores, and had heard about a Dutch architect who was very difficult to work with, and whom she wanted to meet. And that’s where it started. Basically you might say that an anti-architect met an anti-fashion-designer — two people with expanding interests in different fields of exploration, finding many things in common that were not necessarily related to their own disciplines. This was at the end of the 90s, a long time before I joined. And the first phase of our collaboration was dedicated to research into the brand which eventually led the first store designs. Then we started a second phase to actually work on more ephemeral projects; events, digital campaigning, fashion shows, videos, etc. This was also OMA’s first collaboration in fashion. A total exploration.

What is your role in this exploration?

For almost a decade, I have been responsible for a variety of projects, ranging from fashion shows’ stage set designs to videos like the Real Fantasies series, special projects for their Instagram accounts, events, design, some smaller editorial projects — and then our expanding collaboration into making exhibitions at Fondazione Prada. I have the opportunity to look at the Prada group from many different points of view.

These multiple viewpoints attest to Prada’s architectural approach to fashion, which has set them apart from other fashion brands. How does Mrs. Prada and her team approach fashion space — from the aforementioned runways, to their stores and the Fondazione? And how does this correspond to your vision?

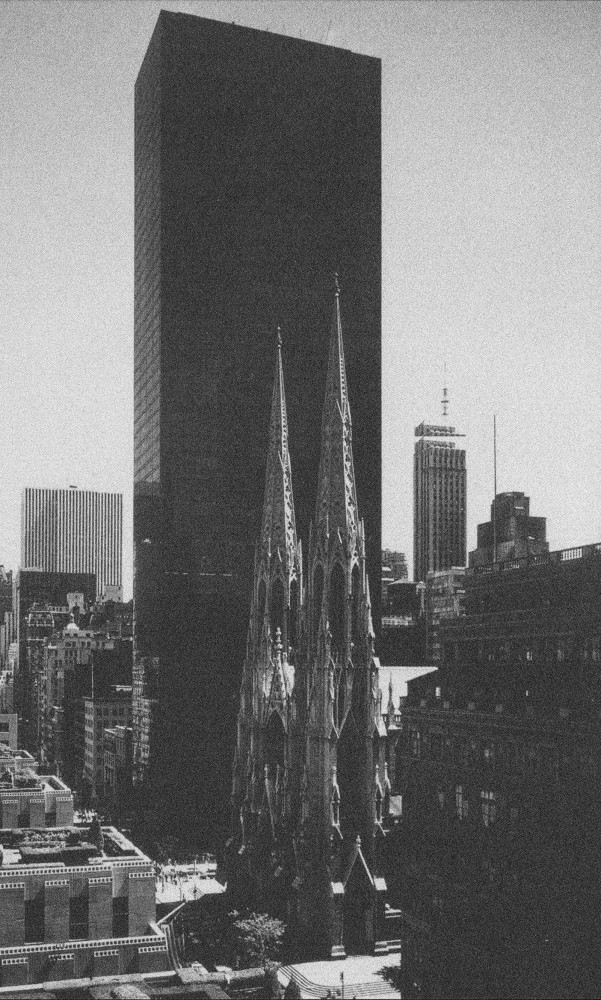

They are all very different projects. First of all, we don’t do stores now. We designed two stores for Prada, one in New York and one in L.A. So the projects that I work on are projects that help to build the aura of the company, and contribute to the stage what the company stands for. In a way we are more free, because we don’t work strictly in the commercial domain: we don’t need to sell. When we design a fashion show we never start with a brief from Mrs. Prada or anyone at the company, but we build one together through a number of exchanges. The creative process between the two companies is very osmotic. Normally, we try to write a script where we define the context in which things happen. It’s a theatrical process in a way; we give shape to the context which then is inhabited by characters — the users, the models, the fashion designers, the buyers and so on. It all starts from that script. So it’s really like writing a play. We need to have characters, and we need to have a context for those characters; the context becomes the stage set, and the characters are then dressed in the fashion that represent a certain idea of a person today. In that sense, the approach is similar to other domains. What is different, though, is that we deal with a brand with strong and consolidated values; Prada stands for certain things, so in the spaces we create we try to maximize those values; putting these values on stage, so to speak.

The Prada group has plenty of space; it’s a fashion house with not just an atelier, but an HQ, an arts foundation, and multiple stores worldwide. How has it been to have access to and make use of all that space for you?

I think Prada is very interested in research in general, in the process of making, and the research that comes in the process of making. Every fashion show, every event, every online project are a form of experimentation. We know the way to approach the creative journey, but we never know where the journey will end; it’s a sort of open-ended process. With the Fondazione, it was a little bit the same. It started from an idea we discussed in the beginning of the project, to actually provide the new museum with a repertoire of spaces that would allow multiple kinds of curatorial combinations; from very large to very small, to provide experiences that range from the very intimate to the very public and collective — basically a machine for the arts, able to accommodate anything that a curator or an artist would imagine. That degree of experimentation I think is common to the whole selection of projects that we work on with Prada, but obviously the timing and the scopes are different from project to project.

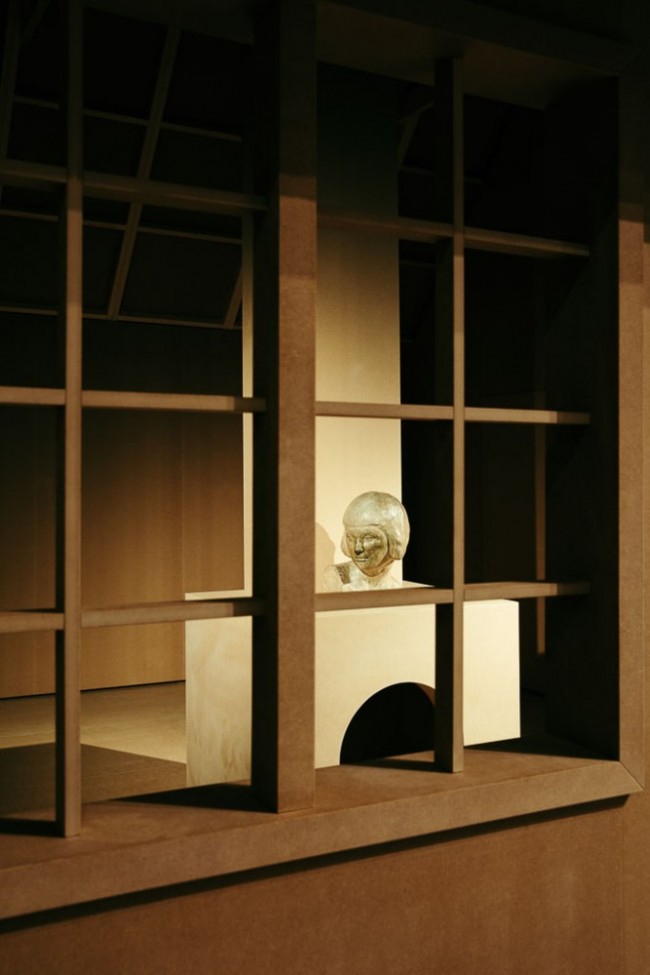

Exterior view of Fondazione Prada in Milan, located in a former distillery that was transformed by OMA, led by Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli. Photo by Bas Princen.

When creating Prada catwalk sets and stages you’ve continued to experiment and challenge the format of the fashion show. How do you understand the space of the runway show and its scenographic elements?

A runway show is architecture in its essential form, and it’s pure performance; the space doesn’t have to be functional, and it doesn’t have to respond to real uses. The only thing it needs to do is to stage the fashion, and to orchestrate the experience between the audience and the models through time. When you look at the history of the fashion shows that we designed with Prada in the past ten years, we went through multiple phases. The first shows were questioning the mechanics of the show itself, and instead of having the models walking back and forth on a straight line, we began to distort this and arrange the public in different ways. That sometimes led to questioning some of the rules in fashion. To make an example six years ago for the Spring Summer 2012 men's show we designed a perfect grid of blue foam cubes that attempted to challenge the hierarchies of fashion, which normally puts the most “important” people in the first row, the second most “important” people in the second row, and so on. We created this completely democratic field, where everyone had the same privilege point to the fashion. So it almost had a political connotation. After these first phases, where we were reshaping the way shows were traditionally conceived, and reshaping the politics that are embedded inside a show space, we began to stage more theatrical and more ambitious projects, designing real scenographies around the fashion. The scenography part goes in two directions; one is celebrating the space and the other is staging a role-play.

What context does the runway space provide for your work as an architect?

You could say that it’s great for an office like ours to actually design fashion shows because it’s a pure architectural and scenographic exercise. Our work with the shows actually provides a huge degree of inspiration and experimentation, which the rest of our office uses. It’s a creative engine in a way. There’s another thing that happened, and that I think is interesting to mention. After we began to work in fashion, we began to work also with performing arts. After a few years designing fashion shows, I received requests to work with operas, biennials, theaters, to design scenographies in performing arts and dance. Usually people who come from a scenography background end up working with brands, whereas we did the exact opposite. That proves, in a way, what I was telling you, that the process is truly theatrical. It is a form of theater — a project that unfolds through space and time — and that, as a methodology, it can be transferred from fashion into other cultural domains.

A double page spread of Wallet magazine No. 4, “Shamans of Space.” Available now.

The office certainly seems to benefit from working with fashion spaces. Do you think that Prada’s architectural value has benefited them?

I’d like to think so! Like you said, it’s true that they were among the first brands thinking about their spaces, and investing in a collaboration with an architect. I think what is really good about Prada is their idea of not delivering a brief. When you establish a collaboration you normally say, “I’ll hire an architect, and give him a brief, and I want him to follow it.” Or, you can say “I want to engage in a dialogue. I want us to learn from each other, and create an open process, and therefore I will benefit my company from this dialogue.” I think we both benefited from this dialogue; we became more interested in fashion as a process, and they became more architectural in return. From the Fondazione, to the Transformer pavilion that we built in Korea, to the whole season of fashion shows, these are all projects with strong architectural attention — established and consolidated through the years. Nothing in Prada happens without thinking about the space, and what space means for them, and this extends beyond new designs into the location scouting, which we do a lot for them and that is never casual. Their spaces have a very strong, emphasized meaning.

This might be related to the different spaces of fashion again, but what are your thoughts on fashion exhibition-making versus the runway, which has historically been fashion’s mode of presentation?

That’s a very interesting question, and I’ve worked on a few. The space that an exhibition provides is to actually unveil the process of fashion-making, the cultural imagery behind it, but also the craft and the materials, the technology and research that go into it. Basically a fashion exhibition unpacks the work of a fashion house from multiple points of views and tells a much more complete story, something that also delivers the complexity of the entire process, both from a cultural and business perspective. I don’t think it’s about staging particular garments as opposed to others with a nice backdrop: I think it’s about really giving a sense of complexity and of the speed of the process. A fashion house producing eight collections a year, and all the intelligence and work that go into each one, can be unpacked in a beautiful way in the form of multiple exhibition formats, staging the history of the brand, the material studies, the trials and errors, external collaborations, etc. The exhibition can take many forms. It could look like a lab, as fashion is highly scientific. It can be very inspiring to look into the artistic references, contemporary or historical; it can be about talent and drawings and an exhibition can take the form of a wunderkammer. A fashion exhibition can take many shapes depending on the point of view from which you want to look at fashion. It’s the most exciting thing; it’s an ecosystem in itself.

And how does this apply specifically to your work with the Prada Fondazione exhibitions? Prada is a fashion brand with a very comprehensive art collection, and I can only imagine that it’s interesting to create spatial experiences with and around that.

Prada is very strict about keeping the Fondazione separate from the fashion brand, which I think is a very healthy attitude. But at the same time, the person running the Fondazione is the same person running the fashion house, so there is an inevitable osmosis between the two.

A double page spread of Wallet magazine No. 4, “Shamans of Space.” Available now.

The distinction between the Fondazione and the fashion is there, but how do you distinguish between spaces of consumption or retail and display or presentation in your mind and practice?

Our spaces have to do with the representation of the brand, whether they exist digitally, like for example when we produce short clips or movies for the web or physically, in the shows or events. We are not displaying products. We don’t work on the Prada stores — it’s a completely different exercise. Sometimes it’s interesting to think about the two as layers of the same project, that they can exist together. When we designed the one store in New York, it was meant to act as a store — to sell products, but also to represent the brand and what it stands for through non-commercial activities. It was conceived as a stage for performances, talks, music events, projections, etc. This has become common strategy now-days. Every store is trying to undo the look and feel of the store to instead provide “experiences”; they want people to stay there because they need to buy and whilst buying, meeting different experiences: the store needs to be an archive or a library or an art gallery, people need to be able to play, listen to music, dance, interact in the space — every store is doing this today.

I definitely welcome this development: it allows one to be more experimental, to work on spaces that are more interesting. At the same time I feel there is a relentless search for the new. Everybody is questioning, “What is the store of the future?” while it’s impossible to say what will happen next year. This is why I think it’s more exciting to tell stories about things that we can grasp, for now at least. Use a retail space to stage processes, inventions, stories about our present, and how fashion plays a role in that. And that discussion is liberated from any compromise in a way.

Even though you have only worked on one store for Prada, I want to touch on the department store/shopping mall idea. It is a historical typology of fashion consumption, and you have worked on projects with several of the most prominent ones, including Galeries Lafayette and KaDeWe. You mentioned a lot of these questions surrounding this space. How do you see its relevance in today’s consumer landscape?

We did an exhibition on Galeries Lafayette a few years ago, and one of the most striking pictures that we found going through their archive is a picture of Édith Piaf singing in front of Galeries Lafayette in 1951 during the general strikes in France. She said she chose that place because it is the true collective space of Paris, where people from all social segments would meet. So department stores are interesting because they are truly public spaces, and they’ve been at the center of constructing European modernity. In the decades following WWII, it’s where people got to know about other places. One would go to Galeries Lafayette to get to know about the design coming from London or Italy or Germany, as one would in all department stores around Europe. They acted as cultural embassies in a way. In the 1960s and 70s they had a very strong profile, enhancing cultural ambition, employing great graphic designers, artists, product designers and architects to collaborate with them. After a few more commercial decades, this attitude has clearly re-merged. They are social aggregators, and that’s why they contribute so actively to the life of city centers. Their advantage is that they offer a variety of activities and a scale that allows them to act as lively social platforms. And the idea of the department store as an urban collider is stronger than in other retail experiences. Personally I find the department store more democratic and accessible than a boutique or a brand’s store; you’re not necessarily questioned to buy, and that’s a huge liberation. The department stores do face a great challenge, but there are interesting models around.

Many of the discussions I have with department store designers or clients are about how to deal with the online-offline relationship. Everybody says that the landscape of acquisition, of merchandise, of retail has changed dramatically. That is not completely true, in the sense that the department store is still able to provide an experience and a range of contexts to different products that cannot be replicated online. It’s much more of an immersive experience with the contact between customer and people on the floor, but also, the possibility to link different products to one another stages a lifestyle that is always special and original. And all this can be inhabited in real life. However, I think the past five years have been extremely interesting because these department stores have come to be much more conscious in their design. You might find floors where an entire lifestyle is unpacked and curated as one single scenography, with books, with music, with cinema, with clothes and fashion, with food, graphics, documentation — as one single entity. It’s almost like a new take on the domestic, a domestic that becomes public. So there’s also a shift in scale.

-

Architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli photographed by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm for PIN–UP.

-

Architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli photographed by Anuschka Blommers and Niels Schumm for PIN–UP.

The shift to consider the relationships between online and offline spaces is quite radical, and affects every aspect of life. Are there spaces, offline, online, or metaphorically that you feel you don’t have access to?

As a consumer, not even as an architect, I would be interested to understand more about the economies behind retail or the fashion industry in general. What is the carbon footprint that they actually mobilize? Particularly in terms of climate or economic impact. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drafted a long time ago — before the internet — in a social, economic and cultural landscape that was far different from today. It would be interesting to understand what new human rights can be considered when we talk about citizens/users/consumers. I would just like to know more about the economies behind what I buy. I would like to protect my privacy. I would like to own my data, or at least decide how and when my data is used for commercial purposes. I would like to understand what environmental policies are addressed by brands and corporations, and how they relate to the products that I buy. That’s something we can barely address today as designers but that brands could and should address. Some are doing it, but not entirely. It’s become another marketing tool. It simply would be interesting to know more, and that’s the domain I would like to access.

This speaks to another question we always want to know: is there room for change, and if so, what kind of change do you think is necessary?

Change is endemic in this business, so there is always room for change. The problem is whether the change is really relevant or not, but that’s a different question. I think what will happen is that there will be more and more sophisticated orchestration between the online and offline experience. They will coexist and they will synergize. I think we will see a stronger osmosis between the two; what you cannot do online becomes a very tactile and physical experience offline, and I think that’s the most exciting thing. We will design spaces that are much more seductive and much more tactile, but they can be accessed first from an online interface. In the work that we do with and for Prada, we try to blur the two, and to understand what role an online presence can have in the physical world and what presence the physical world can have online. The grey area between the two is the most exciting at the moment for me.

This also defines today’s media landscape, with the complex relationship of physical and digital publishing and exploring different forms of broadcasting. I agree with what you say about maximizing tactility, sensibility, and collectability of the physical spaces that you create, which is also the case in print publishing — a lot of people predicted the death of print, but print is not dead. It’s rather about maximizing and adapting the physical spaces to how we consume information today, in print and in the real world. And then obviously collaborating with a strong digital presence.

Totally! People like to have beautiful things around; you never have to forget that. And I think that the digital projects make the physical projects better too. The pointless ones have been wiped away, but the very good ones have survived. The impact of the digital has resulted in better products in the physical. But the two no longer work in opposition, but rather form a continuous experience. I do think what will change drastically is the role of social media. It’s already starting to crack after all the scandals in the last few years. People are much more conscious of the limits and discrepancies between what you get and what you think you get. That will probably shift everything into a completely different dimension, combined with the impulse of AI and the disappearance of digital intermediaries such as social networks.

Lastly, what is the future of fashion spaces?

I don’t know. I really don’t know what will happen next year, so it’s very difficult to understand or to project any real thinking. I seriously don’t know. We live in a sort of continuous presence today, and the present is exciting enough.

Buy the full issue of Wallet 4 "Shamans of Space" here.

Cover of Wallet magazine No. 4, “Shamans of Space.” Available now.