Issey Miyake’s Homme Plissé And How To Escape and Define Cultural NarratIve

Issey Miyake started Homme Plissé in 2013 applying his signature pleats to a new menswear concept. Pictured: Homme Plissé staff at the then-under-construction Tokyo flagship.

My sample of Homme Plissé arrived inside a cloth pouch folded to the flatness of a tablet. The cloth of the pouch, impossibly white, crisp, almost translucent, like a perfect cotton, was not cotton. Polymer-based synthetics like this are common in medical exam rooms, and enact the idea of a natural material, rather than the material itself. My new pair of pants had come wrapped not in cloth, but in something transmuted and engineered into the concept of cloth. The significance of Issey Miyake’s work lies in this difference.

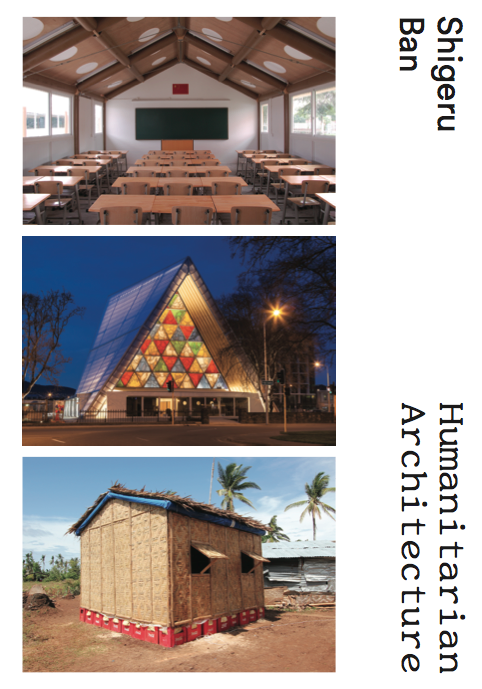

Homme Plissé debuted in 2013 as the menswear reprise of Issey Miyake’s then 20-year-old Pleats Please line, an ongoing play on the designer’s unmistakable signature, a gill-like, svelte pleat. Historically, Miyake is the most cited clothing brand in the architectural press (other than perhaps Prada), and the master has fraternized with at least two generations of architects and designers — among them Tadao Ando, Shigeru Ban, Frank O. Gehry, Shiro Kuramata, Nendo, and SANAA — who either designed stores for him or with whom he collaborated on store designs, installations, or product. The most recent Homme Plissé store in Tokyo, which features an industrial pleating machine, was the work of designer Tokujin Yoshioka, himself an alumnus of the Miyake design family prior to opening his own office in 2000.

But Miyake’s resonances with architecture and design spill way beyond the market logic of co-branding and asking big names to design his stores. With Gehry, he shares a penchant for shapes and volume, with Carlo Scarpa, his love of tell-tale details, with Aldo van Eyck and Gerrit Rietveld, his playfulness, with Alvar Aalto and Frank Lloyd Wright, his translations of material traditions. In Japan, it is difficult to imagine more recent material and process-based architectural practices like those of Ban or Kengo Kuma without him, for his practice has always veered uncannily close to the methods of an architecture studio in its experimentation with machine and computerized fabrication to find novel form. The designer’s forward-thinking A-POC line, for example, was entirely based around a tubular piece of clothing made from a single thread with the aid of a computerized knitting machine. In Miyake’s interests and collections converge an inherently critical eye on design which seeks a steady undoing of our normal, of things we take for granted, like walls and floors, or a pair of pants.

Issey Miyake’s Homme Plissé fulfills the purpose of classic menswear while disavowing the power suit.

Miyake’s pleat concept emerged sometime in the late 1980s through charmed happenstance as a collaborator was folding and pleating a polyester swatch. Once manufacturing had caught up to the idea, a wardrobe of playful monochrome separates, coats, and tunics launched the Pleats Please line in 1993. Homme Plissé collections have translated this basic idea to loose boxier variations, articulated at times with graphic patterns and edge treatments. Wearing Homme Plissé, you are liable to forget your body. You may even forget the garment is there. Instead you find space. Run around in Miyake’s rib-pleat pants and you’ll feel space, as if an abstract concept could suddenly billow against your skin. It’s little wonder that Homme Plissé presentations are usually complex choreo-graphies involving male gymnasts, acrobats, or dancers. Wearing anything Miyake, I’d imagine, is like becoming a concept: in my Homme Plissé I felt as lithe as a soap bubble.

History remembers certain designers as clearly defining the fashion countercurrent of the 1980s, figures such as Ann Demeulemeester, Helmut Lang, Martin Margiela, and Rei Kawakubo, whose differences dissolve in their deconstruction of commonplace clichés of gender, class, exoticism, and success. If the social unrest of the late 60s and 70s explains that generational impulse to dismantle fashion, it had a sure effect on the young Miyake, who can be credited with opening the door to these later transformations. Witnessing the 1968 student revolts in Paris where he was studying fashion, Miyake took a decisive turn towards progressive values of freedom, democracy, and the future. And if his reactions to history have had an emotional resonance, he has, unlike the designers who followed, willfully avoided the symptoms of the Postmodern hangover, be they absurdity, angst, or cynicism.

An industrial pleating machine at Homme Plissé’s new flagship store in Aoyama, Tokyo.

The space, designed by Tokujin Yoshioka, opened in 2019.

As a product of the 2010s, Homme Plissé is both a return and an advance. It fulfills the purpose of classic menswear and yet it disavows the power suit and corporate sleek. Its shapes and colors are simple, its volumes and details are playful, its images are joyous with a tinge of melancholy, because simplicity in adult life always drags around a ghost. Homme Plissé is pantomime in cloth, as architect Aldo Rossi’s work was in brick. A mime — if you can picture the great Marcel Marceau — identifies, restates, and returns a common gesture to its most startling essence, making it strange and familiar at the same time, a silky feather against the goose bumps of consciousness. We, in turn, receive the gesture as if it were completely new.

What would art and architecture be without the pleat or fold? After all, is not the queerness of matter collapsing back on itself in excess, wayward and yet controlled, a fundamental gesture in utero and after? It is hard to imagine Japanese culture without it, but to Miyake, through his education and varied interests, physical matter both defines and escapes cultural narrative. Homme Plissé, like much of Issey Miyake’s body of work, restates and returns a simple concept like clothing so that we can experience ourselves all over again.

Members of Issey Miyake Inc. staff running, wearing Homme Plissé.

Miyake-san usually refuses interviews, but made a rare exception for PIN–UP, answering six fundamental questions:

Pierre Alexandre de Looz: Mr. Miyake, can clothes change us?

Issey Miyake: Design has the power to change lives by enhancing them, offering solutions to contemporary problems, and bringing joy.

Do clothes work differently on the mind than the body?

Clothing has a relationship to the body and, via the body, to the mind. They are inseparable. The space created between the clothes and the body is what interests me and communicates the most.

How might clothes, space, and architecture share a common mission yet follow different paths?

All are different forms of design. Each of the formats above tries to solve problems in our everyday lives from different standpoints, and exists to enhance our lives by bringing convenience, happiness, and beauty. Design is life itself.

You’ve been lobbying for the creation of a Japanese design museum since the turn of the millennium. What should its mission be?

To educate the public with respect to the power of design as well as to showcase the many innovations that have come from Japan. To inspire the next generation to create new forms of design that apply to their time. As I said in an op-ed I wrote for (the Japanese daily) Asahi Shimbun (in 2003):

In an interview, the late graphic designer Ikko Tanaka made the following comment: “Designers feel compelled to continuously explore new directions, but if they face only forward, they have no baseline for comparison.” I think that it is vital for us to recognize the importance of our “design legacy,” which offers itself as exactly that, a baseline from which we can make comparisons. Honoring our heritage in this way might give the Japanese the incentive and courage to move forward.

Should one ever be skeptical of technology or tradition? Or both?

I am not interested in trends or gimmicks but one must always be curious and open-minded. I look for new ways to move forward only with those technologies that allow you to both honor and incorporate the traditions of the past while creating something new for the present and future.

Where do you find inspiration?

Everywhere in the world, especially in nature.

Text by Pierre Alexandre de Looz.

Photography by Brigitte Lacombe.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.