BEIRUT DIARY: Three Days With The Architect Raed Abillama

There’s no better way to get cozy with a city than through the architecture and the architects who live there. This is especially true in the Middle East, since you just can’t believe what you read in the press. With Beirut-based architect Raed Abillama as his generous host, PIN–UP’s editor at large recently spent three sizzling days in the Lebanese capital, trying the levantine lifestyle on for size. Turns out, it’s a good fit.

A topographic map of Lebanon: “The overall Lebanese reality, caught in a cat’s cradle of geopolitical ties”

Day 1: RESET YOURSELF

The doormat to any city may well be the state of the roads and driving in Beirut offers a crash course in local politics. As we inch forward in a clunky van, two burly men, one “riding bitch,” rocket at us on a makeshift moped. They are clearly passionate, so I picture them on a date. But, I am nervous. Traffic here is a tenuous flirtation with disaster, a gorgeous, fume-choked high-tension ballet, that achieves balance through motion. It mirrors the way people talk about the overall Lebanese reality, caught in a cat’s cradle of geopolitical ties.

I mistake a traffic cop for Humphrey Bogart in a well-starched military uniform, his slow motion draw on a cigar is so Old Hollywood. I lose track of time trying to decipher the tailgate of trucks graphically tattooed with graffiti, logos, and pin-up girls. It’s mesmerizing. Beirut’s old tramways are apocryphal and the carcasses of public buses languish in dump yards. Public transportation here amounts to ride-sharing and privately-run, hop-on hop-off mini-buses. I see jalopies out-muscle big, bulging SUVs. Income inequality may be blatant, but in this city somehow the road seems to belong to everyone.

Beirut’s famous traffic at sunset: “A tenuous flirtation with disaster, a gorgeous, fume-choked high-tension ballet, that achieves balance through motion”

In the end, our van gives the moped right of way. The architect Raed Abillama, who chaperones much of my discovery of the city, recommends resetting my expectations. “It’s part of the game. If you get irritated, it will likely cost you too much energy, so with time you learn how to deal with everything in a chill-pill kind of way,” he says chuckling. This nonchalance perfectly captures the way Raed speeds his black Porsche along highway M51, the backbone that laces up and down the Lebanese coast, through most of the major cities. Raed’s great grandfather, a Druze nobleman who wanted to restore his family fortunes, won a licensing agreement for the Model-T directly from Mr. Henry Ford himself and all the other Abillama enterprises followed suit. (There are many.)

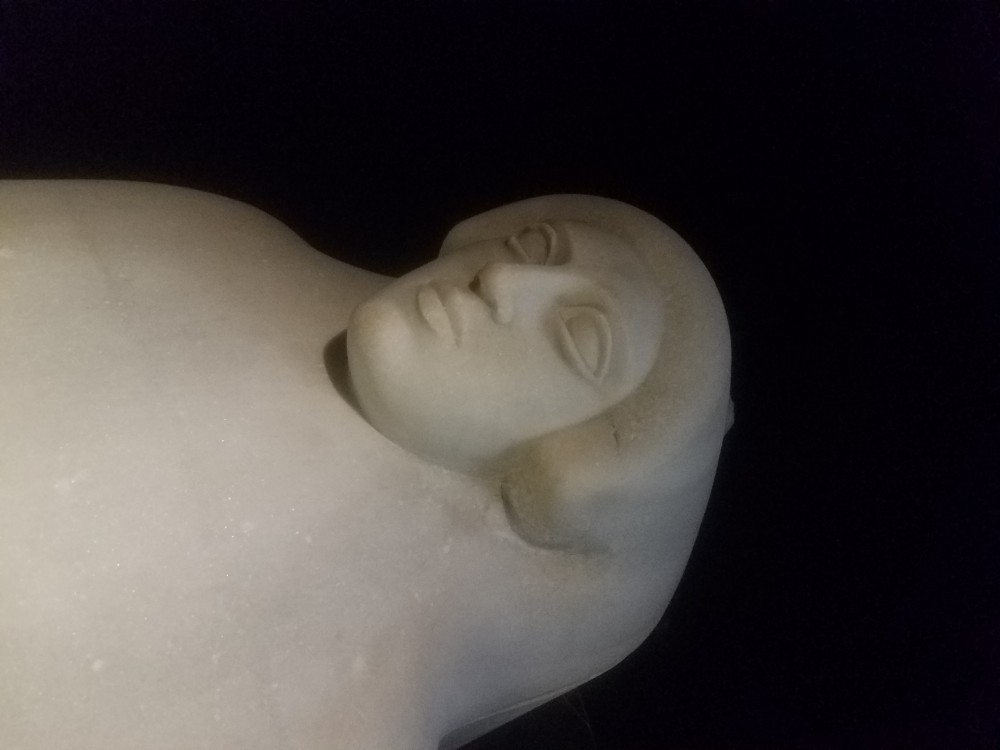

Hellenistic Sarcophagus at the National Museum of Beirut, Lebanon’s principal museum of archaeology: “Our references are so merged between cultures”

In the evening, I try being a pedestrian, which is surprisingly doable in downtown Beirut, where the traffic seems expelled by a magical forcefield. “Beirut is a different species of city,” Raed tells me, suggesting that of all the forces shaping the urban environment, public governance is not one. The private sector tends to fill the vacuum and in controversial ways as it did in downtown, the pet project of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, a prodigal son who returned in 1992 after a spectacular start in the Saudi construction industry. Few architects that I talk to are fans of Solidere, Hariri’s Company for the Development and Reconstruction of Beirut Central District, which seems to have engaged in what might be considered slum clearance.

Then again, glance at photographer Fouad Elkoury’s shockingly beautiful images of civil war Beirut and you have to believe the psychic impetus to replace, restore, and forget. I get a sense of the emotional conflicts facing the place, when I set eyes on a charred and blistered ruin affectionately called the Egg at the southern edge of the district. Designed by Joseph-Philippe Karam in 1965 to be a movie theater, it could hatch a Godzilla baby from its mammoth hull, or a dream of a futurist Beirut. The Egg is iconic in a different way than some picture-postcard Roman ruins, a Maronite cathedral, a majestic mosque, or a grand-slam Zaha-designed shopping mall, which also anchor the district, but its real future in the hands of Abu Dhabi Investment House seems uncertain. Like the Egg, the sprawling and incredible 1961 Starco Center by Addor & Julliard and the 1954 Azarieh office building by André Leconte, an ode to colonial modernism, may be what really make this neighborhood worth a fly-thru.

I’m later told by a financial news correspondent that the Middle East parks its oil money in Lebanon, a place where banking secrecy is a major boon. Viewed from downtown Beirut, it appears a sizable share of it sits in real estate and hospitality. “As soon as you shift from the public to the private sector, you are getting yourself into trouble,” Raed meters his assessment of the district. Who knows, maybe things will change now that the country has began licensing its sub-sea gas fields? When it comes to his city though, Raed explains, patience is key. “To create a downtown that works, with a mixed cultural scene, you have to accept that you are making a city for the people and not a minority of the people. It took centuries to grow to what it was. It is like landscaping. It takes time. You plant seeds and then wait for it to flourish.” Meanwhile, the district offers luxury shopping and upscale watering holes. Tonight, down from the Tom Ford store, restaurants buzz with beautiful people and I get some memorable sightings of trout pout — Lebanon’s plastic surgery industry, I discover, is very popular.

Day 2: SIGNATURE DISH

The color of bougainvilliers bushes in Beirut are burning my retina. Like new construction which boomed nearly a decade ago and with which it still competes for space, bright Mediterranean flora grows willy-nilly over old ochre masonry. In the trendy neighborhoods of Gemmayzeh and Achrafieh, where curated boutiques and minimalist coffee shops mix with Ottoman-era and French Mandate structures in various stages of disrepair, I lose count of the leafy greens that randomly pop from rubble niches like vegetating snipers.

Three tiers of planting in the courtyard designed by RAA (Raed Abillama Architects) for Villa G: “The hanging garden adroitly swaddles the eye, perfumes the air, and blocks the backsides of the neighbors”

Raed has concocted a similar effect in the courtyard of a townhouse that we visit together in the area and which he recently restored for a Lebanese CEO (also known as Villa G). Raed swiftly numbers the lemon, orange, cyprus, and Italian oak trees that climb high, narrow tiers overlooking the outdoor sanctum of this house — his team handles landscaping in addition to interiors and architecture. His design for the hanging garden adroitly swaddles the eye, perfumes the air, and blocks the backsides of the neighbors. The dulcet weather leads me to imagine the countless rooftop, garden, and pool parties that must happen every evening up and down the densely urbanized coast.

Inside, atop a crisp marble mantle, a small landscape painting by Lebanese artist Etel Adnan commands the parlor floor facing the yard; Adnan’s work, which will enjoy a traveling retrospective this coming year, includes artists books and tapestries, mixing earthiness and abstraction. It perfectly captures a reified vernacular, not unlike Raed’s approach to architecture. In this case, for example, Raed has restored the trio of tall pointed arches that typically divide the honorific salon of an Ottoman townhouse with slender columnettes of solid Carrera marble that are so pure and lithe, I desperately want to lick them like a popsicle.

Detail of the arches dividing the salon of Raed Abillama's personal home: “Slender columnettes so pure and lithe, I desperately want to lick them like a popsicle”

The homes that I visit today and that Raed has lovingly doctored, all meld transformation and restoration into something indecipherably new. In another refurbished villa, Raed has accented a historic shell with salvaged architectural details and has collaborated with local design guru Nada Debs on marquetry. When she and I meet the following night at a swanky party, she is introduced to me as “the mother of design” in Beirut. A daughter of Lebanese textile merchants based in Japan, Debs sparkles over a fizzy drink, when she describes her love of traditional craft. She is known, she says, for modernizing Lebanese tradition without the blush of nostalgia, and she doesn’t mind the matronly moniker. The optical storm of clear acrylic mashrabiya — a traditional decorative window screen — inlaid with mother of pearl that she applied to cabinets in one of Raed’s projects is testimony enough.

“Our references are so merged between cultures,” explains Raed as he dispels my idea that there is something called Lebanese architecture. He thinks of design as being true to location, processes, and ingredients in a way that makes me think of critical regionalism, to borrow a term from architectural historian Kenneth Frampton. Raed enjoys cooking, and uses it to explain his point. “I like dishes that are a simple two or three step process with good ingredients. It’s about respecting the ingredients. You want to bring out the best of them. To me there is a strong relationship between cooking and architecture.” He isn’t into architectural froth and there isn’t any at Tawlet, the village-to-table restaurant where we stop for lunch.

In a cul-de-sac off Armenia street draped in drying laundry and balcony curtains — exterior curtains are a ubiquitous shroud over façades — we eat a splendid but simple meal. Tawlet is a socially conscious restaurant spun-off by the successful farmers market known as Souk el-Tayeb. Airy and bright, the buffet-style counter tingles with conversation and the smell of orange-blossom water. Lebanon is celebrating its first major export of industrially grown potatoes, but the menu at Tawlet intends to highlight small farmers and preserve traditional recipes by serving a different regional dishes everyday. Balancing my plate of food as I walk, I notice, and it’s the same in every interior, that the space between furniture is really snug. “Our need for cultural entertainment turns around food. We are into having a big table and guests,” Raed explains. “Big table” is a metaphor. From what I see, even when furniture is standard the Lebanese array a space to warm-up a crowd, force a bump-in, elbow rub, or pat-on-the-back.

Day 3: BOARDWALK EMPIRE

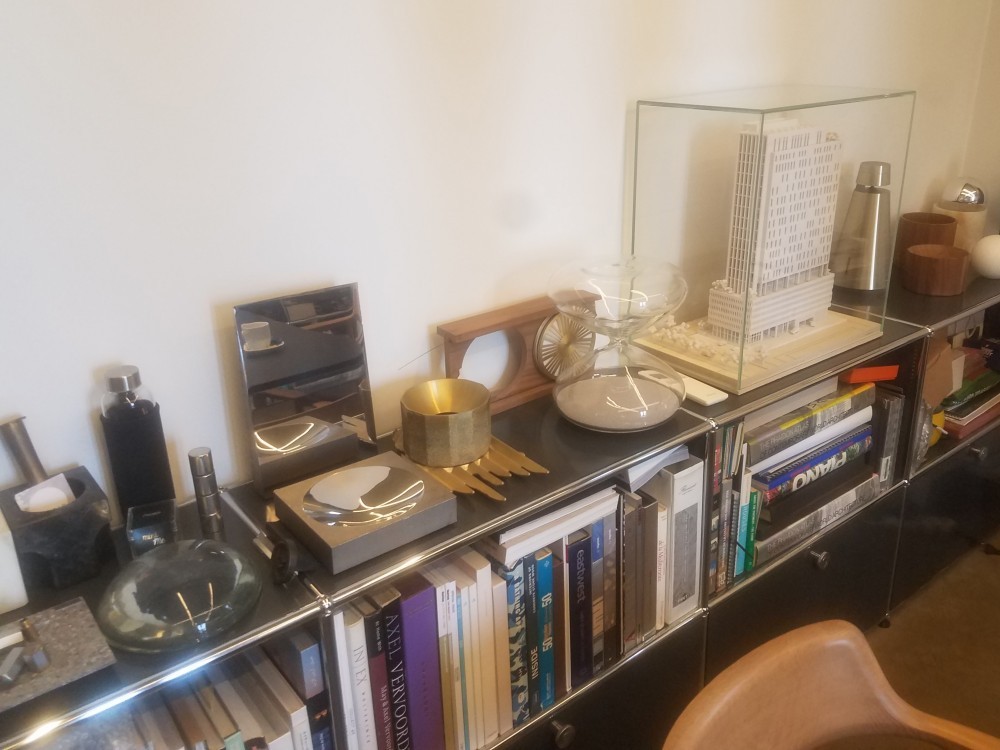

When I think corporate chic, I think USM furniture. The brand’s stainless tube frame and corner ball joints are the chrome rims of office furniture. I discover, however, while snatching a champagne flute to watch the sun set over the Mediterranean that it’s even sexier as a bar cart. The Abillamas represent USM in Lebanon and Karim, Raed’s brother, who hosts us for dinner around an infinity pool, makes the brand work equally well as a disco accoutrement. Floating in his pool, itself floating over the northern fringes of Beirut, I feel exhilarated by this dream home of Raed’s design. When another guest unlaces her exquisite Valentino heels and continues barefoot for the rest of the night, I think that I feel what she feels.

A concrete model of the ABI Chelsea building on the terrace of RAA’s offices in Beirut: “A New York building, tailored for Lebanese joie-de-vivre”

The USM bar cart emerges again in a rendering Raed has produced to show prospective buyers what ABI Chelsea, his forthcoming residential tower in New York will look like, set to open in 2019. The images, full of fastidious details and spiked with cameos of his brother’s collection of contemporary art, are produced by a former student whom Raed taught at the American University of Beirut. He excitedly points out that his young collaborator trained as an architect and is also a member of the popular Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila. Their queer sound has been garnering attention for its melancholy, heartfelt portrayal of Lebanese social life, including gay love, which says something about a country where “any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature” is criminal. For context, Lebanon is still reported to be a liberal safe-haven in the Arab world. There’s some poetic justice in the mix. Raed’s New York building, tailored for Lebanese joie-de-vivre, rises from a Chelsea lot purchased from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, an iconic artist whose queer legacy has yet to fully emerge from behind a veneer of modernist machismo.

The coastal landscape in Lebanon has a rough masculinity all its own, but nothing other than gentility graces the air when we finally make it to IXSIR winery. “Is this Lebanon?” Raed recounts thinking as he first visited this historic manor on a hilltop. None of the usual sprawl or signs of trash landfills that have made recent headlines are visible from this breathtaking perch an hour north of Beirut. Raed restored the limestone building where Syrian soldiers once squatted, and before that noblemen farmed the land. He also buried a state-of-the-art winery below it in a design that has won accolades.

-

Steps leading up to the IXSIR winery’s historic manor: “Where Syrian soldiers once squatted, and before that noblemen farmed the land”

-

Outdoor seating at the Abillama family’s XSIR winery, an hour north of Beirut: “Is this Lebanon?”

-

Entrance to the IXSIR winery’s main building.

-

The IXSIR winery’s main cave.

The understated design of IXSIR seems to make the surrounding countryside more idyllic than it may be. You have to watch a film like Georges Nasser’s 1957 film Ila Ayn (Towards the Unknown) where a farmer abandons his family with the hope of making his fortune in Brazil, to get a sense of melodrama of this setting. The American-Lebanese wedding-party dining behind us probably came in search of a similar sense of homecoming besides IXSIR’s excellent, mineral-laced rosé. In some senses, Lebanon is what writer Salman Rushdie has called an “imaginary homeland,” since more Lebanese live outside than inside its borders. Almost anyone, especially a tourist, could feel settled in this magic spot.

View from rooftop bar at the David Adjaye-designed Ashti Foundation, overlooking the Corniche: “The coastal landscape in Lebanon has a rough masculinity all its own”

What does a foreigner have to see to understand Lebanon, I ask Raed. “The Corniche is the only place that represents Lebanon and Beirut, it’s different ethnicities and religions,” he says of the famous boardwalk that rims much of the city’s coastline. “We all own the Corniche. It’s really the only public space,” he adds. In 2014, his office threw their hat into the public ring, partnering with the municipality to rehabilitate the Horsh Beirut, a forest only a quarter-of-a-century old and meant to be free of access. Ethnically diverse neighborhoods border the park, which is another reason Raed likes the initiative, but the valiant effort remains stalled. The Corniche, however, delivers, especially when recognizing a tourist. My cabbie takes the “quick” way, and idling in the morass of traffic, I have plenty of time to notice that it is here that Beirut’s muscle queens come to preen. I also have ample time to admire equally meaty sights, like the colorful 1957 Sham’s Building by Joseph-Philippe Karam, or the masterful Headquarters for Electricity of Lebanon (it is better viewed from the city side) opened in 1972 and designed by P. Neema, J. Aractingi, J. N. Conan and J. Nassar. As is the case with Raed, who studied at RISD and then Columbia’s GSAPP, many of these architects studied abroad and were as cosmopolitan as they come. So, why are these wonderful creations not in our history books?

“We are a small country. We are always willing to welcome other cultures. It may be the colonial aspect, as if foreigners have something to bring us, something we can learn. Our entire culture is based on adapting,” Raed tells me as I attempt at placing modern Lebanon somewhere on some cultural map. On my last night here, at the Discotek Beirut Waterfront, I’m staring at three scantily clad, nymph-like acrobats seated on inflatable sea-horses and suspended from a construction crane over my head. They twirl. I want to gape but I can’t. They are ejaculating golden confetti as the music thumps. Tequila flows. Two boys make out over my shoulder. The architect in me wonders if this is what Rem Koolhaas had in mind when he fawned over Coney Island. I am also thinking, I am on a pier. I am in Lebanon. This is delirious Beirut and I could adapt to this just fine.

Text and images by Pierre Alexandre de Looz.