100 Years of Castiglioni: His Geologist Daughter Digs Into the Designer’s Layered Legacy

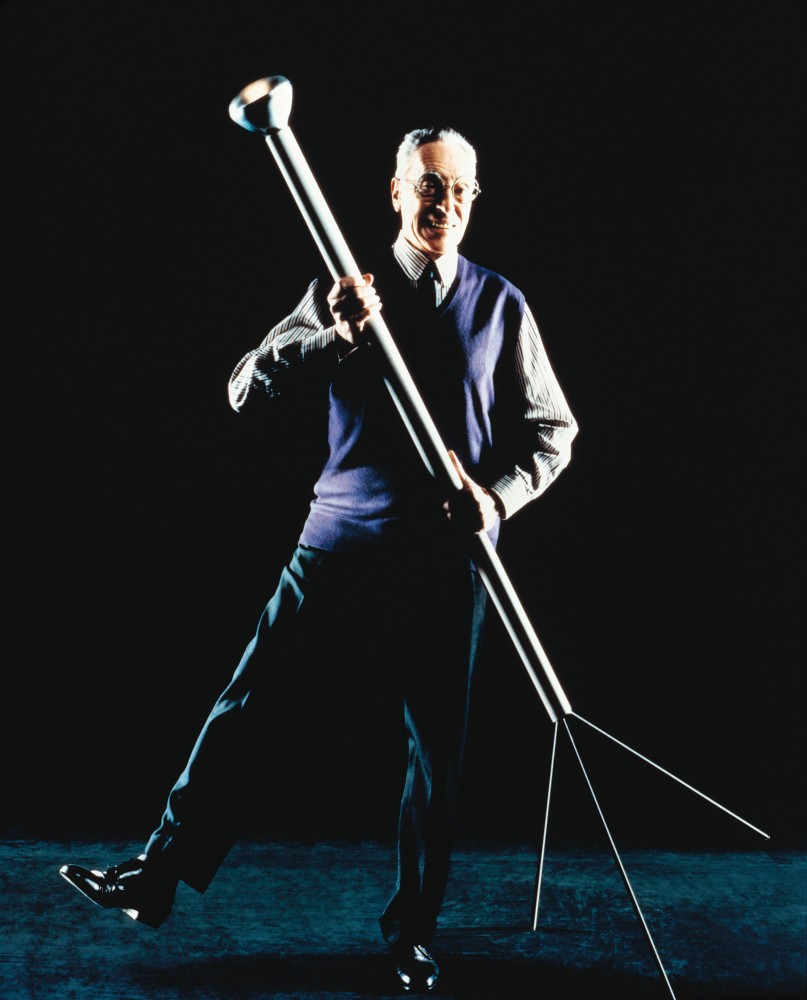

Portrait of Achille Castiglioni by Jean Baptiste Mondino.

The late Achille Castiglioni is one of the most iconic figures of post-war design. Trained as an architect, Castiglioni first worked alongside his brother Pier Giacomo (who died unexpectedly in 1968), and later on his own. Born in 1918 in Milan, Castiglioni would have celebrated his 100th birthday this year. Fittingly, 2018 has been one of much celebration of all things Castiglioni. The year kicked off with the exhibition If you are not curious, forget it at both the Milan and New York flagships of FLOS, the Italian lighting manufacturer who was one of the designer’s most important client (the brothers' 1962 Arco floor lamp remains one of the company’s bestseller to this day). But it is at the Triennale in Milan that Castiglioni is really in the spotlight this fall. This week marks the opening of A Castiglioni, a comprehensive survey show curated and designed by one of his former students, Patricia Urquiola (together with Federica Sala). While the designer himself is no longer able to give insight into his work, one of his daughters, Giovanna Castiglioni — a trained geologist who is also responsible for the family foundation — allowed us a glimpse into her father’s expansive oeuvre and humor-filled attitude.

Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Arco floor lamp (1962); Produced by Flos.

Your father died in 2002. Do you look at the work, at his legacy, differently now than you did back when he was still alive?

My father had a really funny way of working and his work still surprise me to this day. As a result, I’m never really sad about his passing because his work is still around and I still discover something new about it all the time. For instance, I grew up with the Parentesi lamp (1971, together with Pio Manzù); it sitting on my desk, in my room. Now I can understand all details have a good purpose behind it. For example, in the Parentesi lamp, there’s a weight of five kilos floating on the floor and now I can understand there is a tension, there is friction, there is sound when you move the light up and down the steel cable. So when I was little, in my childhood this was just sound. Now it’s a functional sound. It is part of the project. So even in this single lamp, I am constantly discovering and beginning to understand all the details, because I now know they all have a purpose behind them. My perspective is really different because I have to learn my father. And since I’m not a designer, I not only have to learn everything about him as a man but also about him as a designer.

How many designs did he produce in total?

In total 298. But not all of them are still in production anymore. And that doesn’t include the hundreds of architectural projects, exhibitions, and other many other things.

The Parentesi Lamp, 1971 by Achille Castiglioni with Pio Manzù.

When you were growing up, and even up until the time of his death, were there designs of his you didn’t like, or that you’ve only grown to appreciate over time?

Of course. The Brera light, for example (1992).

Is that the one that is shaped like an egg?

Yes, the egg. It was associated with a painting (The Lamp, 1919, by Mario Sironi) that is really famous in Italy, which is at the Pinacoteca di Brera. But now I can also understand that Achille designed this lamp because he loved eggs so much. And I love eggs so much! (Laughs.) Now it all makes sense.

Was there a difference in the way he designed together with his older brother Pier Giacomo (1913–68), and the kind of work your father did on his own?

When Pier Giacomo died someone wrote that the two men shared a brain. Well, this was true because they had a wonderful relationship. They respected each other, they grew up together, but there was no competition.

-

Sanluca armchair (1960); Produced by Gavina (1960), Bernini (1990).

-

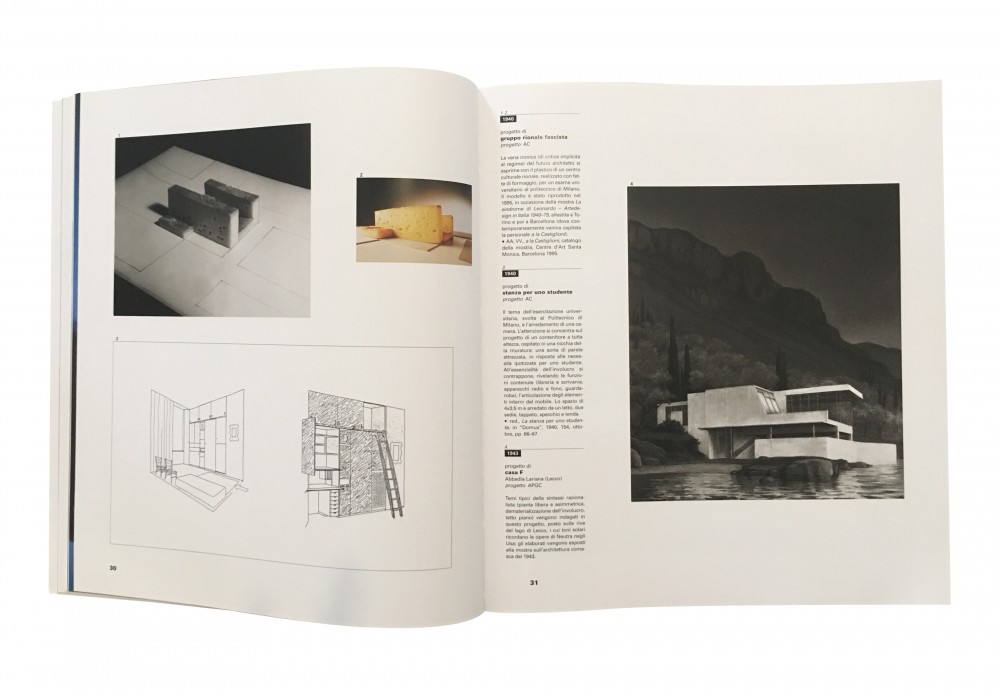

Clockwise from top left: Achille Castiglioni, Model for Fascist District Group (Gruppo Rionale Fascista) as a student at the Politecnico in Milan (1940); Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Drawing for Casa F, Abbadia Lariana (Lecco) (1943); Achille Castiglioni, Room for a Student (1940).

-

Left: Achille Castiglioni and Riccardo Arbizzoni, Presbiterio chair prototype (1973) for Del Piccolo & Ridolfi; Achille Castglioni, Linda bathroom fixtures (1973); Produced by Ideal Standard (1977).

-

Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Gatto and Gatto Piccolo table lamps (1962); Produced by Flos. Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, Arco floor lamp (1962); Produced by Flos.

-

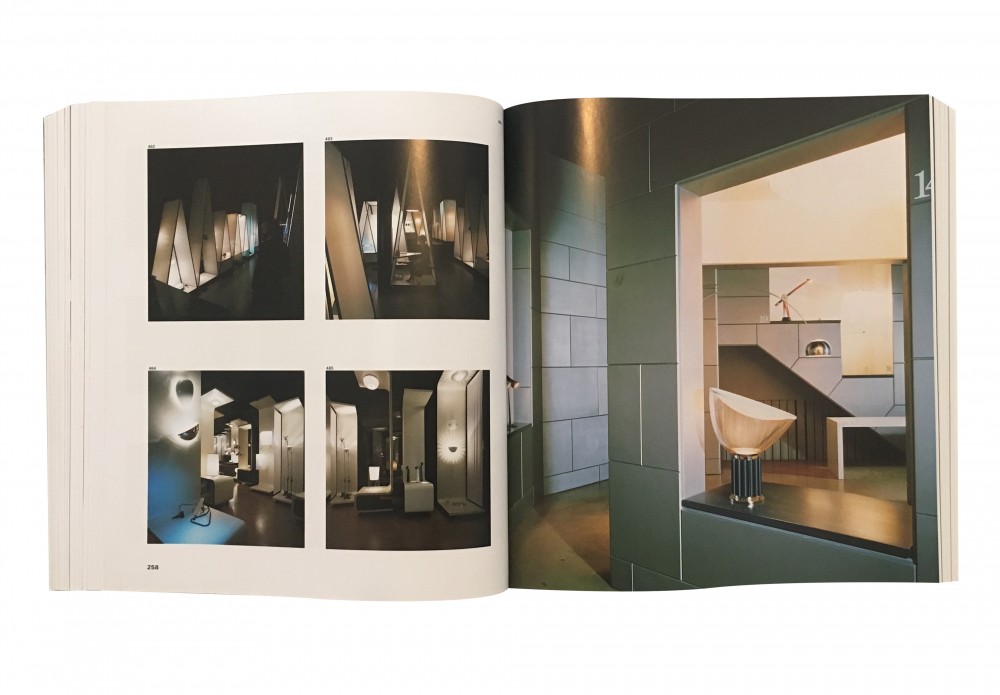

Interiors of Flos showroom at Monteforte 9, Milan. Achille Castiglioni with Paolo Ferrari (1976, 1984), and Italo Lupi (1990).

-

Clockwise from top left: Achille Castiglioni and Paolo Ferrari, Trac table (1976); Produced by BBB Bonacina. Achille Castiglioni, Bibip floor lamp (1977); Produced by Flos. Achille Castiglioni, Cena table (1977); Produced by Zanotta.

-

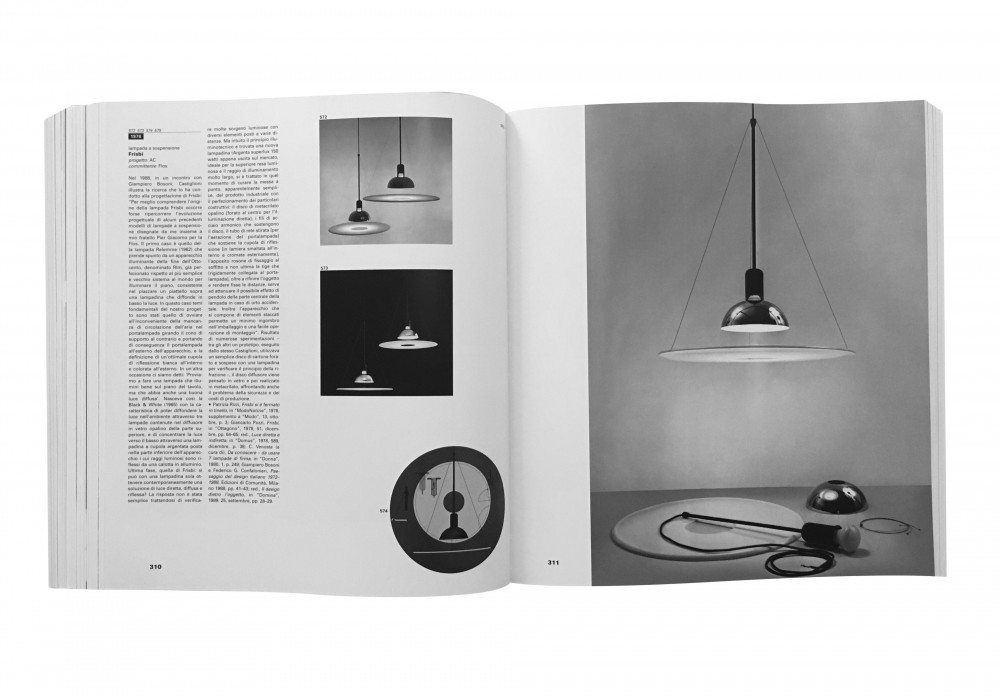

Achille Castiglioni, Frisbi lamp (1978); Produced by Flos.

-

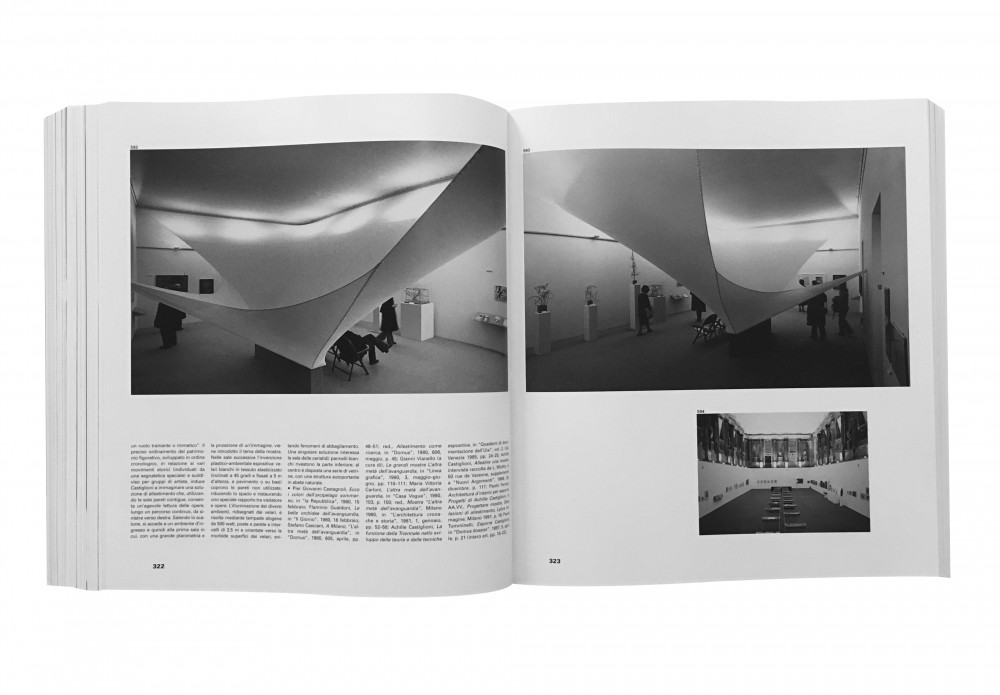

Installation views of "l'Altra Metà dell'Avanguardia" (The Other Half of the Avant-Garde) at the Palazzo Reale in Milan (1980) by Achille Castiglioni.

But you never met Pier Giacomo?

No, unfortunately not because Pier Giacomo died in 1968 and I was born in 1972. But I studied Pier Giacomo. He was a very good designer and he sketched in a very good way — his technical drawings are impeccable. And then Achille would make the prototypes. They way they worked was very complementary. There was also Livio, the oldest brother (1911–79). He was an architect too. Livio was more like an engineer while Achille was more interested in light and sound. And my grandfather was a sculptor (Giacomo Castiglioni, 1884–1971). Pier Giacomo was really serious. My father was crazy, and Livio was the craziest. As you can imagine, the family was really close, really united, and they were very playful.

You’re a trained geologist. Do you see any overlap or parallels between your area of expertise and your father’s work?

In the studio, we have high ceilings and I think you can feel that there are a lot of layers. Achille stored a lot of stuff — prototypes, technical drawings, invoices, contracts, many photos, catalogues, books. So, it’s like geological layers. I enjoy this work because every day we continue to find surprises in this geological stratification.

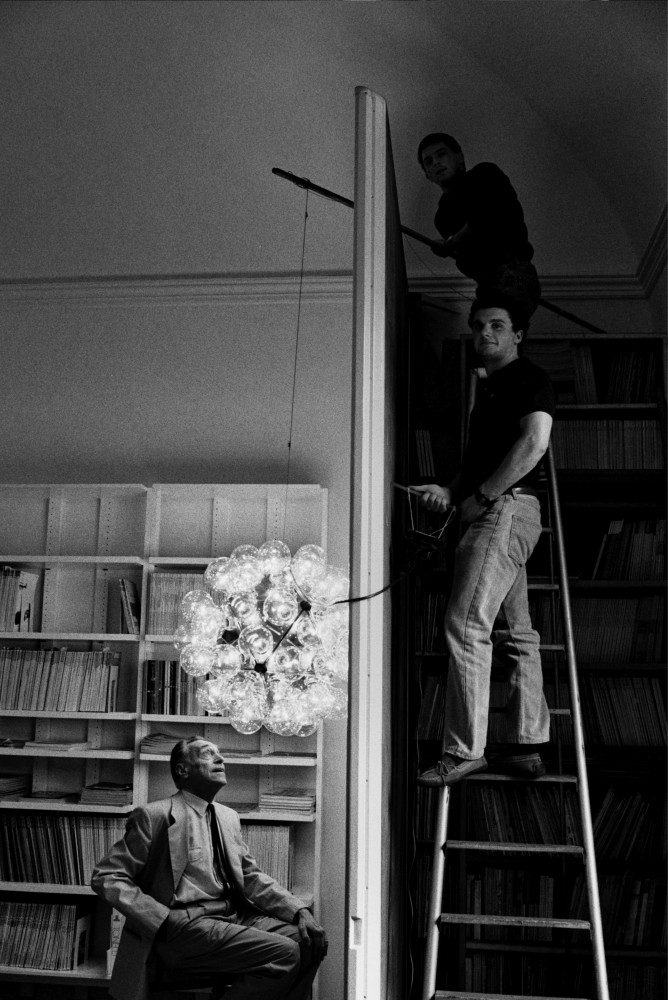

Achille Castiglioni with his Taraxacum light. Portrait by Cesare Colombo.

Have you found a design that was not produced and that has not put in production since your father’s death?

We found sketches about a little candle and a little cylinder up the candle so when you switch on the light, when you use the lighter the cylinder starts to spin because it’s hot. We also found all the sketches and the prototypes of all the toys that Achille designed many years ago. We’re currently trying to put them in production.

Two of the most respected designers today — Patricia Urquiola and Konstantin Grcic — both studied with your father. What influence do you think he had on them?

There’s also Michele de Lucchi because he’s also an architect and a designer and was really close to Achille as well. He worked with Sottsass, but he is really similar. But definitely Patricia Urquiola and Konstantin Grcic. But it’s hard to say what influence he had because there are many designers who keep a little bit of Achille with them. It’s amazing because they keep alive part of his. I’m very happy because I can see in all these designers sometimes a little idea, the functionality, sometimes the irony, and sometimes the great sense of humor. You can see it and it’s amazing. It’s like thinking of Achille like a cake, and everybody gets their slice.

Interview by Felix Burrichter for PIN–UP Online.