SOFT SCHINDLER: Reflections on the House

On the occasion of Soft Schindler, a design show curated by Mimi Zeiger at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood, PIN–UP and Zeiger invited artist Ian Markell and writers Leslie Dick and Susan Orlean to reflect on the exhibition and Rudolph Schindler’s architecture. The result is a pocket-sized publication designed by Erin Knutson functioning as exhibition catalog. Copies are available at the MAK Center.

-

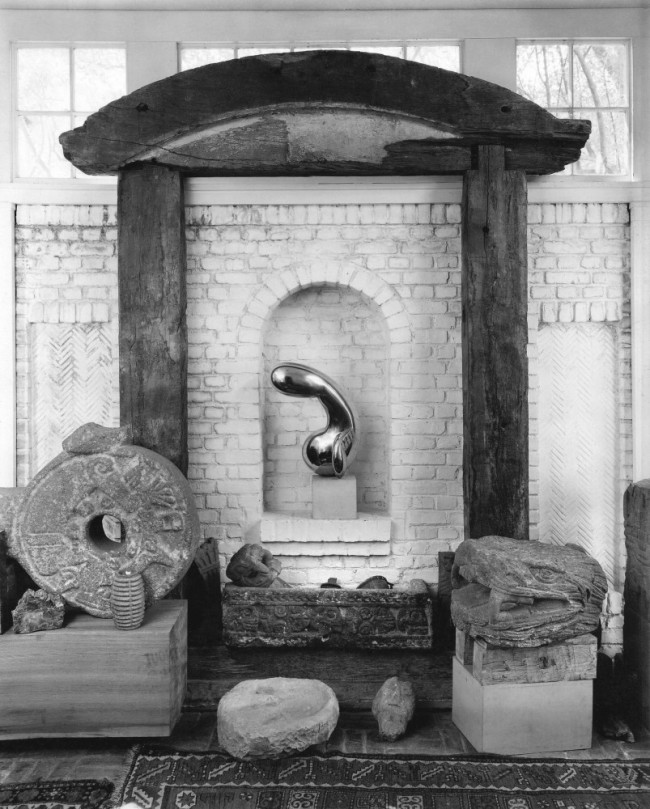

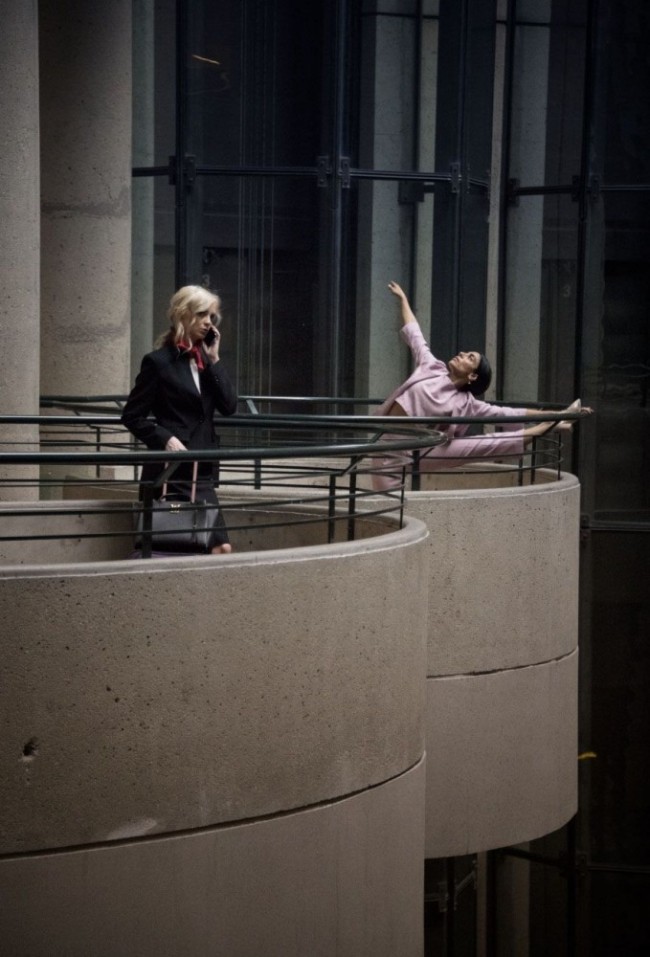

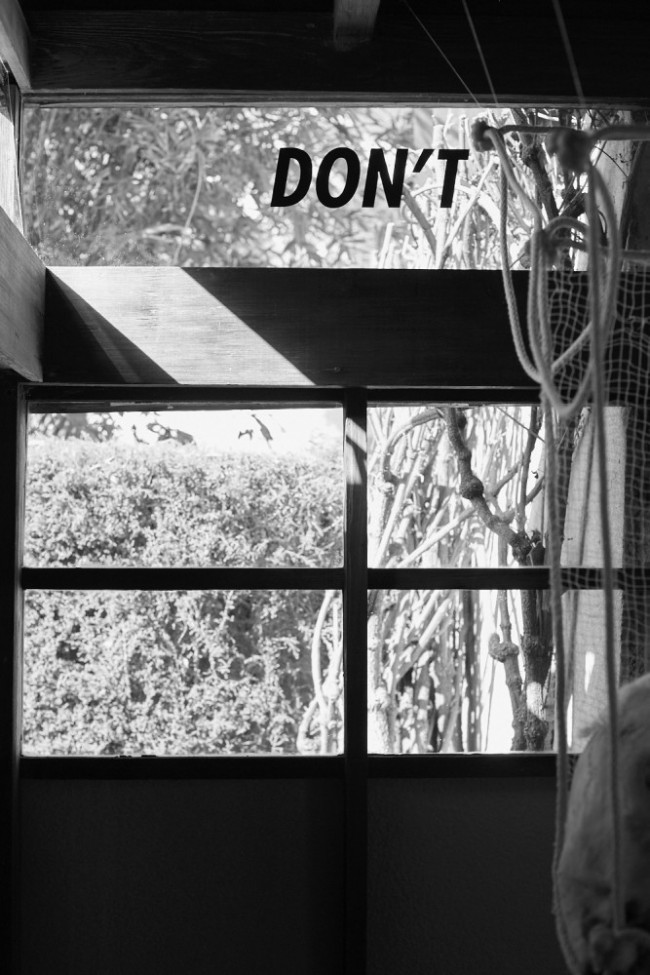

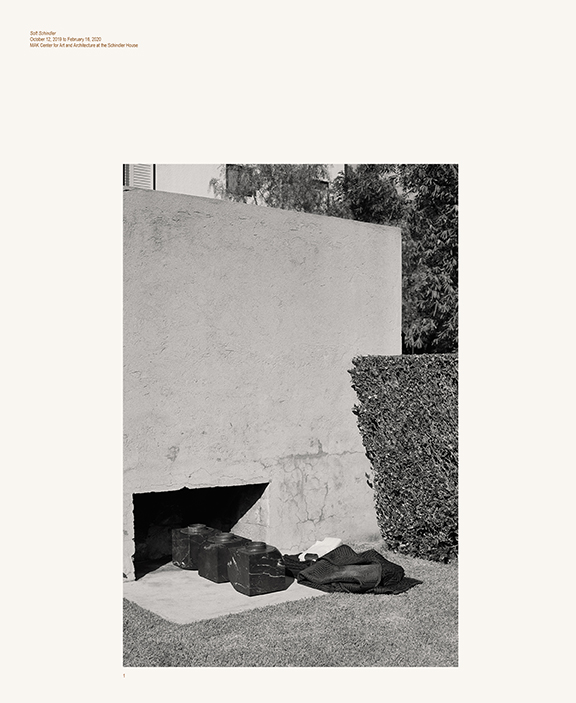

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Page from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

-

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Page from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

-

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Page from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

-

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Page from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

Like clothing, architecture proposes a body, and an embodied experience. Movement, stillness, intensity, reflection: these are effects of space and form. In some sense we are like dancers, choreographed by the architectures we move within and through. And, in many ways, a house is like a body, also; each of them has an interior and an exterior, a set of surfaces and views, entrances and exits. Like the clothes we wear, houses cover and protect, even as they open and reveal. Both fashion and architecture are three-dimensional forms that rely on two-dimensional plans (blueprints, elevations, paper patterns) to take shape. I like to think that sleeves, necklines, and hems, like sliding doors and clerestory windows, perform the erotic function that Freud celebrates in his outline of the erogenous zones that mark the thresholds at the various different exits and entrances of the body. Still, this analogy (of house to body) is slippery: do we put a house on, like slipping on a kimono, or strapping on armor? Or do we allow the house to represent a body, in fantasy, with eyes for windows, the door a mouth, and the garden like a mother’s body, to hold us, or provide a field for play?

I came to live in Los Angeles with Peter Wollen in 1988, like so many others imagining we would stay for a few months. Miraculously we rented one of the Neutra apartments on Strathmore Drive. Our landlord was Dion Neutra; he told us he was conceived in one of the sleeping baskets on the roof of the Schindler House. His earliest memories were of rolling down the small slopes that shape the garden there. Dion came to dinner with us in Strathmore Drive and a minor earthquake took place during dessert. As the table shuddered, the dishes rattled, and the low building rocked and rolled, I was very frightened. Reaching across the table to hold my hands, Dion assured me there was nothing to fear. “Don’t worry,” he said. “My father’s houses are very flexible.”

The concrete walls of the Schindler House, with slim lines of light marking the edges of the slabs, propose another kind of flexibility. The body invoked by the house begins the day with gymnastics, or yoga, and eats lots of fresh fruit and vegetables. It’s a body that moves between the outdoors and the interior easily, in a constant process that undoes the boundaries between them. It’s a body that cooks, and eats, communally, and has sex on the roof. The Schindler House is like a 1920s dress by Madeleine Vionnet: deceptively simple, draped crêpe de chine, and cut on the bias. As with Vionnet, you cannot forget the body that moves within it.

-

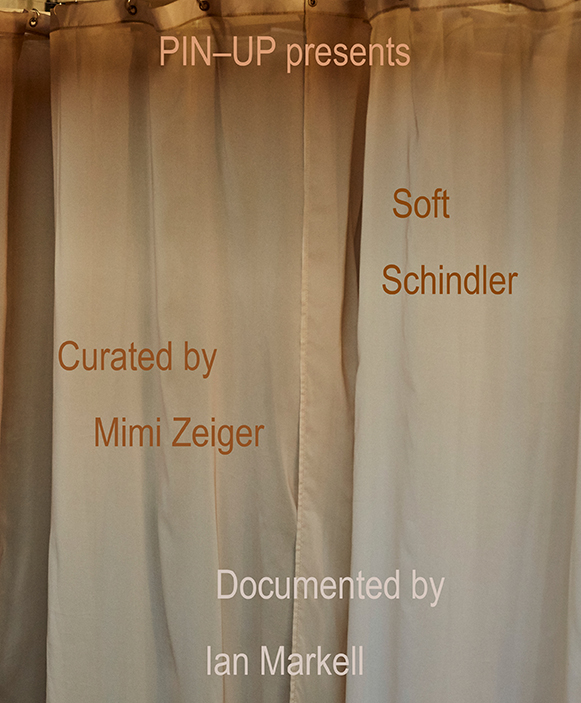

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Cover from the catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

-

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Back cover from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

The plan of the house deconstructs domestic expectations: a space for two couples to occupy, unconventionally. Four large rooms remain undesignated as to their function, while the original plans are marked with the initials of the first four occupants, each of whom had “a room of one’s own.” Where did they sleep? Under the stars on the roof, on a divan by the copper fire? In a sense, as Francette Pacteau said to me, sex is everywhere and nowhere in this little house. With no space specifically indicated for work, or sex, or private thoughts, or communality, all of these activities are dispersed, and multiplied, proposing not only a utopian body, but a new set of relations between these bodies, scattered through the different interior rooms and the various articulated outdoor spaces that function as rooms open to the sky.

Both Marian Chace and Pauline Schindler were pregnant in 1922 while the house was being built, and like an afterthought, Schindler carved a small glassed-in area out of the Clyde Chace studio, to function as a nursery. Still, the scale of this tiny space (and its swing door!) suggests that they believed these growing children would move freely within the open structure, floating between the interior and exterior spaces, and the different rooms, indefinitely. After Dione and Richard Neutra moved there in 1925, Neutra himself took over the small glassed room, to use as a study for writing.

Pauline continued to live in the house for decades after she divorced Schindler, and the ongoing conflicts between them make fascinating histories. In my view these conflicts cannot be mapped onto the forms of the building itself, despite the fact that Pauline painted her walls pale pink and put linoleum tiles on the concrete floors. The building tolerated her interventions, even if Schindler did not, because its logic is open to all sorts of possibility. It’s flexible: it bends and gives. Undoing binaries of public/private, emotional/rational, feminine/masculine, natural/technological, and hard/soft is part of the deep structure underlying the project of Schindler’s architecture.

To be clear, the Schindler House is like a tent, and it is also like a cave. Contradiction is woven into its architecture: “a bundle of opposites” as David Gebhard wrote. It is both light and heavy, made out of concrete slabs and clear glass and wood, with compressed sugarcane fiberboard and stretched canvas as partitions and sliding doors. Narrow glass rectangles placed between the concrete slabs cracked easily, subject to the tremors that animate the Los Angeles basin, and they were difficult to replace or repair. Nevertheless, the light slicing through the heavy slabs produces a rhythm that again insists: there is no single form here, rather a dynamic play of likeness and difference.

-

Ian Markell, Soft Schindler: A Documentation, 2019. Page from a catalog for Mimi Zeiger's exhibition Soft Schindler, designed by Erin Knutson for PIN–UP and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood.

-

-

Detail photograph of the Schindler House in West Hollywood, Los Angeles, by artist Ian Markell.

The house was built by hand and like most hand-made things, it shows. There are flaws and marks visible inside, a consequence of wrinkles in the Kraft paper and other fabrics that lined the concrete forms, different patinas from the soft soap they used to lubricate the inner walls. The exterior concrete surfaces are rough; the interior surface is smooth, like skin or leather, and softly reflective. Chace and Schindler poured wet concrete into a wooden form, placed where the slab would eventually stand. They waited for it to harden, then removed the mold and lifted the slab into place using an ancient technology, a tripod with block and tackle. Only then did they see the inner surface, sometimes smooth, sometimes imprinted with the accidental irregularities of the mold. Like all hand-made things, discovery is built into the process of making, and small differences in surface and reflection animate these spaces.

This house was not expensive to build: Pauline’s parents provided most of the money, yet another example of a wealthy family supporting a revolutionary life. There’s an economy in the construction that matches the dynamic simplicity of the formal structure: part of the logic of Modernism involves taking into account the effort and expense of building the house, within the design itself. Tilt/slab construction methods required a minimum number of workers and relatively cheap materials, while multiple elements have a double function. Concrete slabs face two ways, providing the exterior and interior surfaces of the house; the floor is a foundation, and the gardens are living rooms, while there’s one shared kitchen for two families, with outdoor fireplaces recalling campfires in the wilderness. When it was raining, they took umbrellas up the narrow stairs to the sleeping baskets on the roof, where the canvas covers dripped all night. The Schindler House is DIY, it is a utopian project materialized, and as such it invites us to imagine our own ideals realized, to reconsider our expectations regarding our bodies and shelters, our gardens and bedrooms, our lovers and friends.

Text by Leslie Dick.

Photography by Ian Markell.

Taken from the PIN–UP special publication Soft Schindler, accompanying the exhibition by the same name curated by Mimi Zeiger.