INTERVIEW: LA-Based Architect Jerome Byron On Coming Of Age In The Time Of COVID

Over the past six years, Los Angeles-based architect and designer Jerome Byron has carved out a niche for himself crafting furniture and spaces that combine a laidback approach to industrial minimalism and to the Modernist canon with injections of color and playful nods to hip-hop and skating culture. Take his series of pastel-hued stools, their curved concrete a reference to skateboards and halfpipes. Or retail experiences, like the Hype Williams-inspired flagship for streetwear brand RIPNDIP, a sculptural space defined by custom neon lighting and tubular shelving. At the nearby “manicure bar” Color Camp, concrete and steel are balanced by sunset-like gradients and luscious plants. Byron’s newfound California vibes are a stark contrast to his alma mater Harvard GSD, and to his time in Berlin where he worked for architect Francis Kéré. Byron was born in New York and grew up in Ohio, but his hands-on, can-do approach to construction seems unapologetically L.A., a city where he has quickly garnered a list of high-profile clients. So what does a young architect do when facing lockdown and a pandemic? Isabel Parkes called Byron in his newly built studio in Echo Park to find out.

-

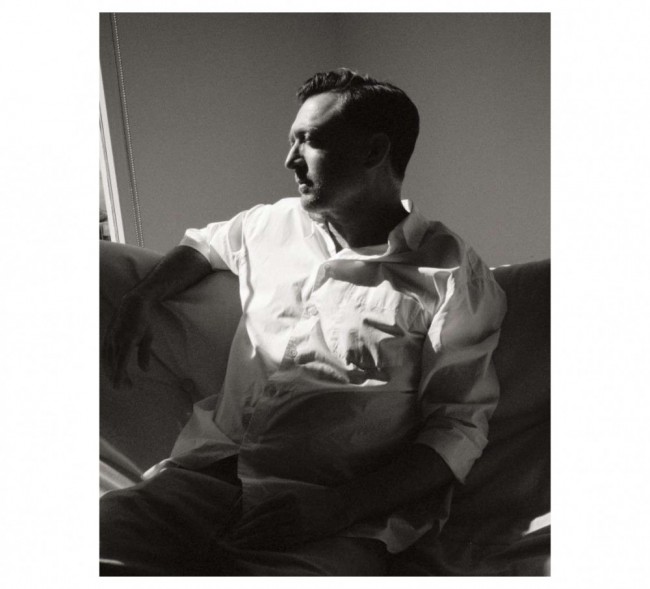

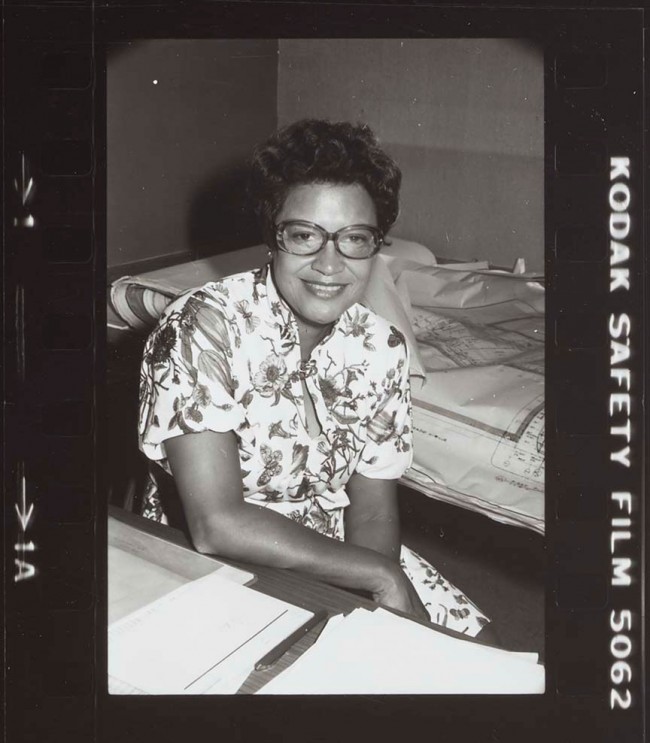

Jerome Byron with his dog Taejo. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Blackened Steel Dining Table (2020) by Jerome Byron made from a single sheet of 11-gauge hot rolled steel and a single 10-foot, 4-inch diameter tube stock. Photography by Luke Sirimongkhon.

Isabel Parkes: How have these past months been for you?

Jerome Byron: It’s been busier than ever, and it all picked up that first week in March. I was actually already renovating part of my workspace when California imposed its lockdown, so then I just went into high gear — masks and gloves on, hardware store runs multiples times a day — and building.

Can you describe your work space?

It’s about 12 by 12 feet within a 650-square-foot studio. Renovating it involved raising and leveling the floor, dropping the ceiling, and furring out the walls, then building in desks, bookshelves, and closets. The walls are lined with cork, and I installed kind of throwback-vibe LED ceiling lights that look like the ceiling tiles from your average '90s office space, but recessed within a red, moody ceiling. I wanted to plug into a warm studio environment that contained all my references.

-

Jerome Byron's Los Angeles studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Jerome Byron in his Los Angeles studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Concrete Stools (2018) by Jerome Byron are available in three soft shapes: low stool, high stool, and broad bench. Photography by Sam McGuire.

-

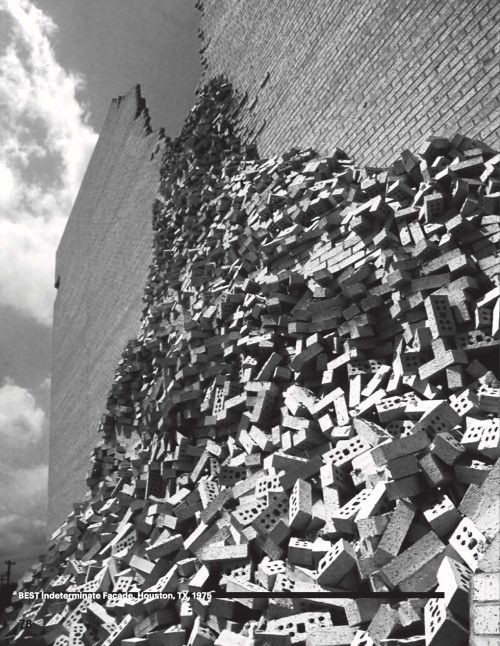

Jerome Byron designed the flagship store for skateboard and apparel brand RIPNDIP, completed August 2018 in Los Angeles, California. Images courtesy of RIPNDIP.

What are some of those?

Images of furniture or pieces that have turned up during my research alongside objects I’ve collected, like skateboards, and books. It matters to me that I maintain a homey vibe and that I would want to or have to work in every single day, all the time.

You’ve skated for a long time.

Yeah, I grew up doing it and I still kinda push around from time to time. I probably skated most throughout college in New York, and I think that experience, in combination with an intense architectural education at Pratt, helped shape my ideas about form, movement, and materials. Skating all around New York and then staying up all night building models and drawing in 3D was definitely when I developed and maybe codified my spatial-thinking sensibility. I designed these glass-fiber-reinforced-concrete stools a few years ago, and when I look at them now, I see that they were very clearly inspired by the shape of skate decks, and the curves and materiality of skate parks, although that wasn’t my intention at the time. I also think that skateboarding naturally exposes you to different places and experiences, many of which I try to instill in whatever I’m making.

-

Jerome Byron in his Los Angeles studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

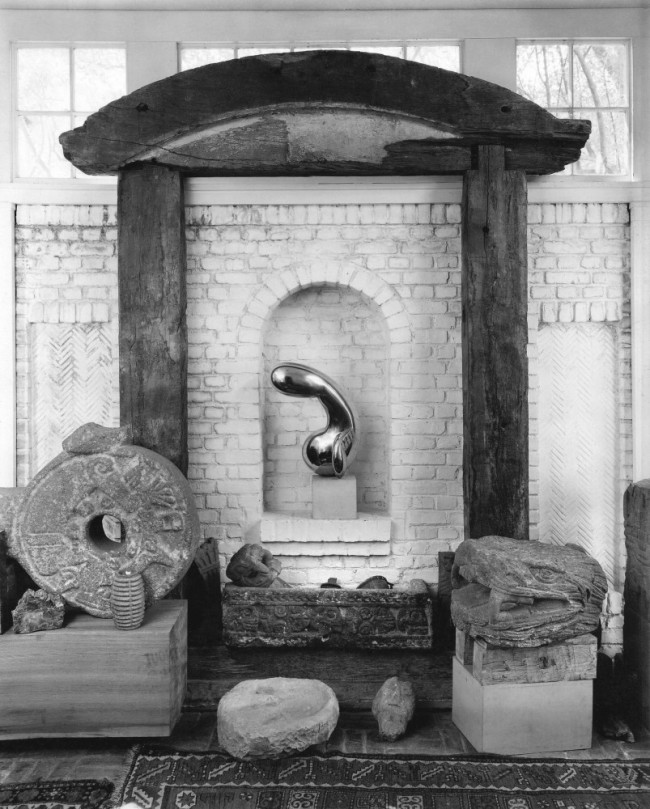

The city of Los Angeles was the inspiration behind the collision of bright colors and industrial materials at Color Camp manicure bar architect Jerome Byron designed together with Weekday Studio. Photography by Jennifer Chong.

How did the pandemic affect your work flow?

The answer to that felt very much up in the air at the start of this. Nobody even knew what the protocols were for going outside. There was a new urgency both to leaving your house and to protecting yourself. At the same time, I had to make decisions. Time was limited, what materials were available was changing, and of course, financially things were uncertain. I didn’t want to break the bank with the build-out of my studio, so it was about being as efficient as possible within a lot of unknowns. Amidst this, work and random little projects were picking up.

Sounds like a thin line between surviving and thriving.

One hundred percent. It’s a new kind of survival mode that moves from making a living to suddenly having jobs coming up and basically saying “yes” to all of them. Before this, I might have taken more time to mull things over or visited the sites. But now, we’re facing the unknown in the sense that we don’t know what next week or month will look like.

-

Jerome Byron in his Los Angeles studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Blackened Steel Dining Table (2020) by Jerome Byron measures 36 inches by 72 inches by 29 inches. Photography by Luke Sirimongkhon.

Did the projects that were suddenly coming up have anything in common?

I can’t get into most of them, but there’s one where I was introduced through friends of friends to someone who’s building a campus for their company. The priorities there were continuing this big campus development with urgency so that the company could operate and still have people there. My frequent collaborator and I had to remodel an existing house into a common space and essentially do a project that would normally take months, in a few days. On the one hand, you don’t have any time to think and on the other, you really are moving forward. Suddenly, you’re looking back and being like, oh wow, we pulled that off. And that in itself is learning. You’re reacting and moving forward.

-

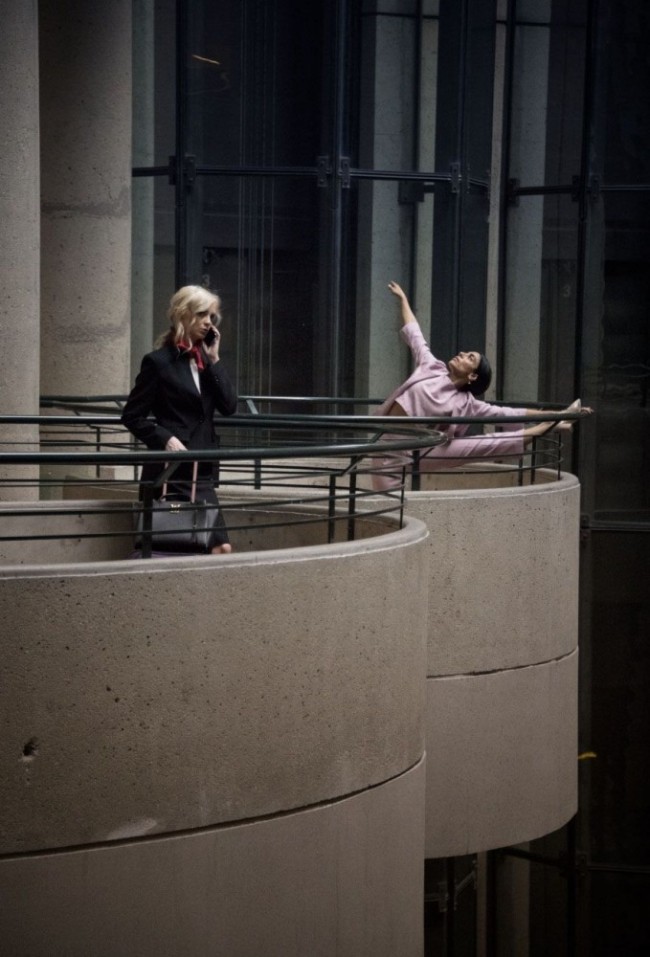

Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Does that mode of working feel sustainable to you?

I’m not sure what’s sustainable. But what I can take forward is that I’ve tested and expanded my own limitations. Even after that first project, we were burnt out. While I don’t think working like this is at all sustainable, you learn how to make quick decisions and move on. Normally, you might have three design rounds planned in and give yourself two weeks for that first round. During the pandemic, the time is much, much shorter. While you don’t want to do things too fast, you also see how fast you can make decisions, jump on the phone, and coordinate people.

-

Jerome Byron in his Los Angeles studio. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

Jerome Byron’s design of the RIPNDIP flagship store features a stark white-on-white palette and custom neon lighting. Images courtesy of RIPNDIP.

As a spatial thinker, how have you found the transition to working remotely?

It requires being plugged in all the time, to all lines of communication. I’ll get a text asking me to jump on a call quickly, and two seconds later, we’ll be Zooming and sharing a screen and making decisions. Before, you would maybe schedule a time on Friday to meet and review some drawings that you did the day before. Now, I’m drawing on screen as we’re videoing, and my collaborator is sharing the screen and marking up the drawing.

Everything’s accelerated.

There were a few weeks at the beginning of the lockdown when I was constantly on the phone checking in with people while also doing my work. And I remember thinking like, “Oh my god, I haven’t been this social in a long time.” And that’s sort of how it feels now. It’s all collapsing in on each other, all happening at the same time, all full steam. The idea of doing this amount of communicating and just rapid decision-making would have never entered my mind pre-pandemic. But it became a necessity and it became normalized — and it is possible. We can be hybrids and hyper efficient.

-

Jerome Byron with his dog Taejo. Photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

The city of Los Angeles was the inspiration behind the collision of bright colors and industrial materials at Color Camp manicure bar architect Jerome Byron designed together with Weekday Studio. Photography by Jennifer Chong.

As you’re saying this, I’m thinking about the various strata of culture in which we’re experiencing the hollowing out of the middle and units consolidating. I see it in relationship to what you were saying. Do you feel that?

Totally. I was both feeling and witnessing that. I was recently doing a site visit at a client’s home, where I designed a ground-up guest house, and the client is the founder of some successful startups, so I was picking his brain a bit, just asking how the time has been for him and his business. He said that the money is still there and investors are still writing checks, but now they only want to work with people they know can pull the thing off. We were talking about how devastating it is for a lot of new people who don’t have their legs yet or who need somebody to take a chance on them. Now everything has become very risk-averse. And that resonates with my personal experience, where I’m getting work only through word of mouth. All my new stuff is coming from other clients or former colleagues, who know I can pull the thing off.

-

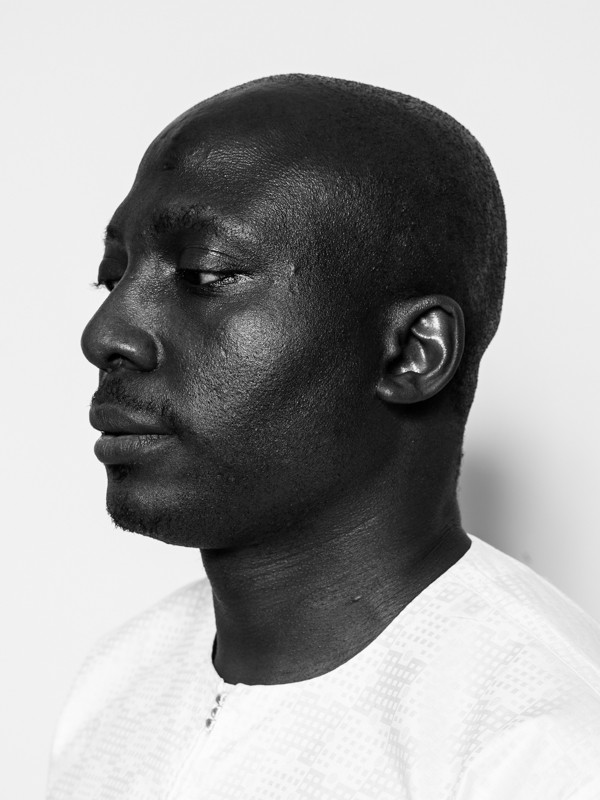

Jerome Byron photographed for PIN–UP by Shane Smith.

-

At the RIPNDIP retail store in LA the brand’s mascot, a cat named Lord Nermal makes an appearance. Images courtesy RIPNDIP.

What do you think architecture can offer us in this moment of instability?

I’ve been having multiple conversations about the different levels of investment in this field. I am working on a project with a client who wants to buy an iconic mansion in West Adams, a once-thriving Black neighborhood in L.A. She basically wants to make an uninhabitable space habitable again. We had this long conversation with her about what it means to really invest in projects that generate meaning and that have long-lasting impact. We discussed bringing in her family of builders and craftsman from the East Coast, as well as other friends and neighbors, bringing in people who want to inject life into this place and neighborhood, into the community. It really contrasts with some of my other, more commercial work, which is also stimulating and fun, but at the end of the day I have to ask myself: “Who does it serve?” So even though I’m busy, I push myself to think a little bit longer and harder about these questions: What are we all doing? Why are we all working so hard? At the end of the day, we’re stuck at home. We can’t spend time with our families. Friends who have lost their jobs are thinking similarly. You’ve spent your last five or ten years working your ass off for a company, and suddenly it’s over. You have to find that meaning again.

Interview by Isabel Parkes.

Portraits by Shane Smith. Work images courtesy Jerome Byron.

Taken from the forthcoming PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.