Architect Anne Holtrop Finds a New Lease on Life in the Desert

Since relocating two years ago from the Netherlands to Bahrain, where he’s set up a studio in the capital, Manama, architect Anne Holtrop has been exposed to different aesthetic influences — strong light and deep shadows — but has also introduced some rather more deliberate changes into his practice — axial shifts, if you will. He’s currently centering his production around ideas of material gesture, the process of finding a specific material’s unique properties in order to achieve a “directness in construction,” as he puts it. Recent projects in this vein include the solo exhibition Casting and Cutting at the Shaikh Ebrahim Center in Bahrain’s former capital, Muharraq (2018–19), the set for Maison Margiela’s fall-winter couture show in Paris (2018), and the design for a section of Al Qaisariya Souq, a historic market also in Muharraq (2017).

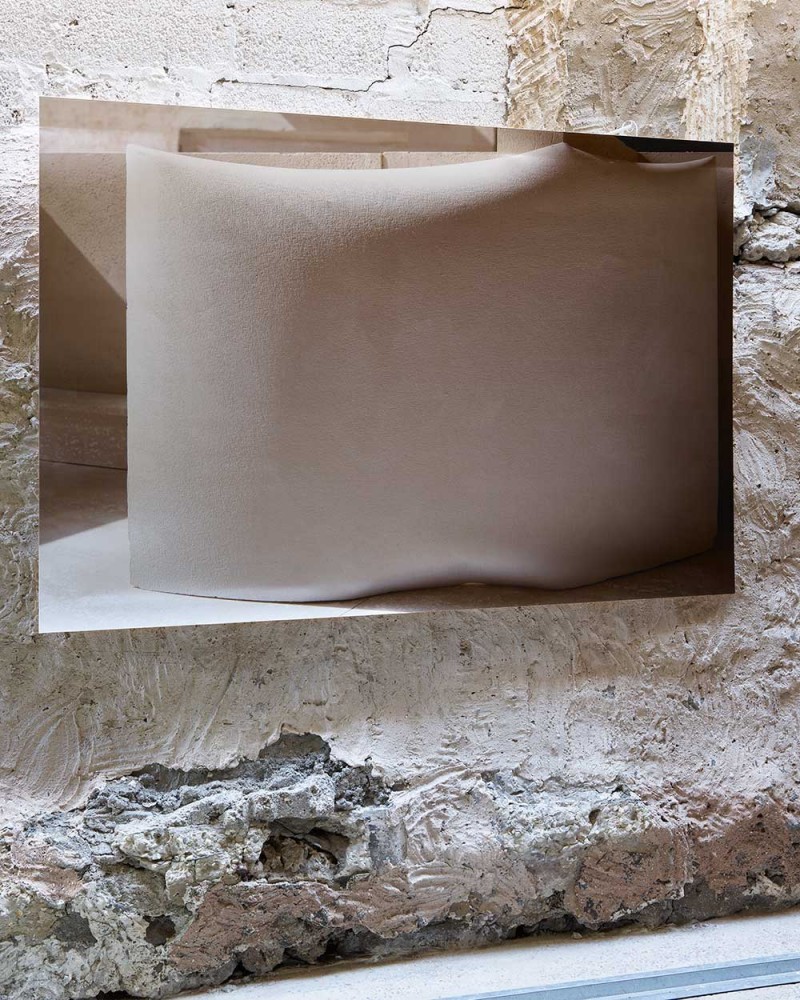

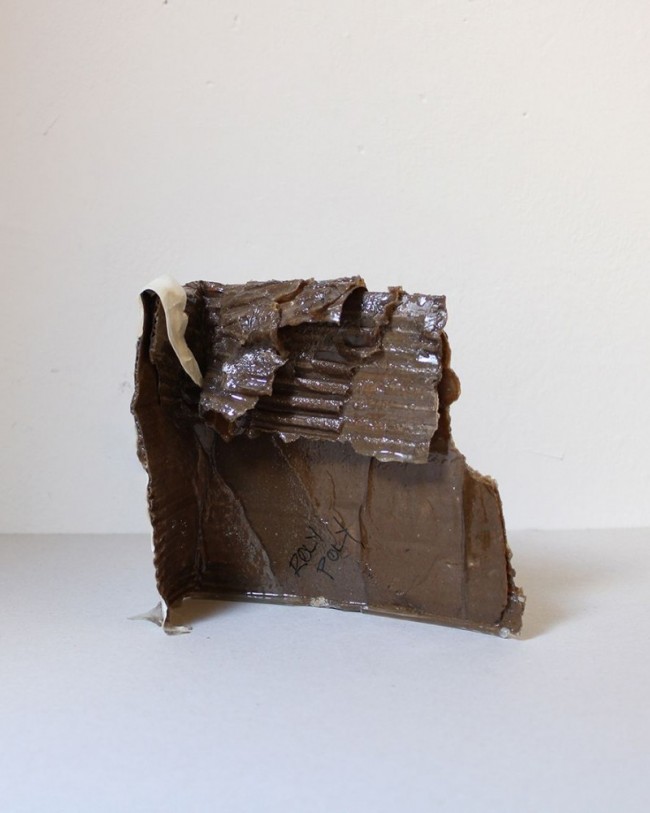

Anne Holtrop, from the Casting and Cutting exhibition at the Shaikh Ebrahim Center in Bahrain’s former capital, Muharraq (2018–19).

The turning point, he says, was Batara (2016), a collaboration with photographer Bas Princen. “I began to see a lot more possibility in Batara; a strong wish to work directly with material and the way I can form it,” he explains with respect to the series of photographs and sand-cast models, as well as a full-scale pavilion in the Netherlands, that grew out of a visit to the ancient city of Petra, in Jordan. The sculptural forms of that work were akin to follies, “not yet matured as a full building principle,” he notes. “Making Batara was about influencing the process rather than realizing a fully designed form.” Holtrop references Richard Serra’s Splash works (1968–69) to illustrate his ideas: Serra hurled molten lead into the corner of a gallery space, which shaped and constrained the fluid matter; form was thus the result of an interaction between environment and gesture. “For a sculptor, perhaps it’s normal, but for an architect to get into such a close relationship with the material — that’s what I’m looking look for,” explains Holtrop.

Anne Holtrop, from the Casting and Cutting exhibition at the Shaikh Ebrahim Center in Bahrain’s former capital, Muharraq (2018–19).

The Green Corner building in Muharraq, which broke ground in January this year, is the latest example of Holtrop’s vernacular shift. Commissioned by Shaikh Ebrahim Center, it’s formally simple — a long shallow block — and uses only the land and material processes as aesthetic ingredients. Employing a simple casting method, the workers made concrete relief panels of the site itself, which were then lifted to form the façade, reifying the surface of the ground as a vertical plane. “It’s an investigation of the relationship between the technique and the context. I see these elements as the three-dimensional inkblots, even fingerprints, of the place. I like things that remain ambiguous,” Holtrop says.

-

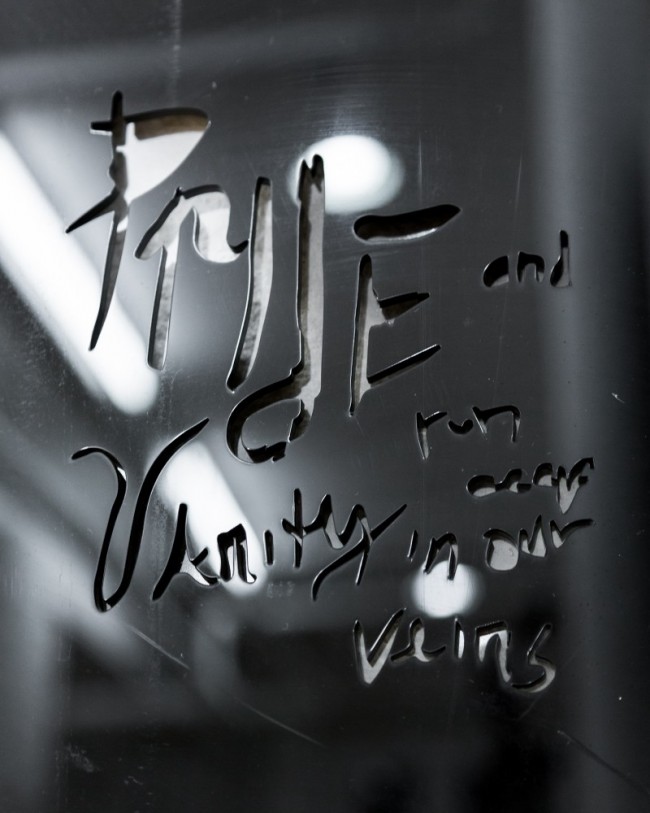

Photos from a visit to a quarry in Cairo, which inspired a new direction for Anne Holtrop's Al Qaisariya Souq project.

-

Photos from a visit to a quarry in Cairo, which inspired a new direction for Anne Holtrop's Al Qaisariya Souq project.

About a ten-minute walk away is Al Qaisariya Souq, a project that illustrates the fluidity of his process. The brief was for a stone building, so Holtrop worked with a quarry in Egypt — soon after they were producing 1:1 mockups of walls and roof sections cut from a single piece of stone. “They told us that this kind of thing hadn’t been done since they built the pyramids! It was completely cut by hand, in the traditional way,” he recalls. Yet he was underwhelmed by his idea once he saw it realized, finding it “too traditional.” While at the quarry he spied some leftover slabs, rough on one side, and instantly changed direction. Since using these stone slices was structurally unsound, a method was devised to cast reliefs of them in concrete. “Researchers in Egypt believe that some of the slabs on the pyramids themselves may have been cast rather than cut, so perhaps we’re doing something very similar,” Holtrop notes. In the history of iconic desert architecture, there’s hardly a greater lineage to claim.

Text by Shumi Bose

All images courtesy Studio Anne Holtrop.