PLEXI DEVIL: The Artist Raque Ford Claims Her Space Through Sculpture

The work of New York-based artist Raque Ford presents an assemblage of minimalist sculpture, abstract painting, narrative fiction, popular culture, and direct personal experience. Her current exhibition 6 Obsessions at Brooklyn’s 321 Gallery is her most ambitious to date with two pieces spanning 70 feet. The works, which are mostly made of acrylic, envelop the viewer, casting back their reflection, and folding them into its historical, material, and maternal drama. For PIN–UP she sat down with fellow artist Paul Kopkau for a personal one-on-one.

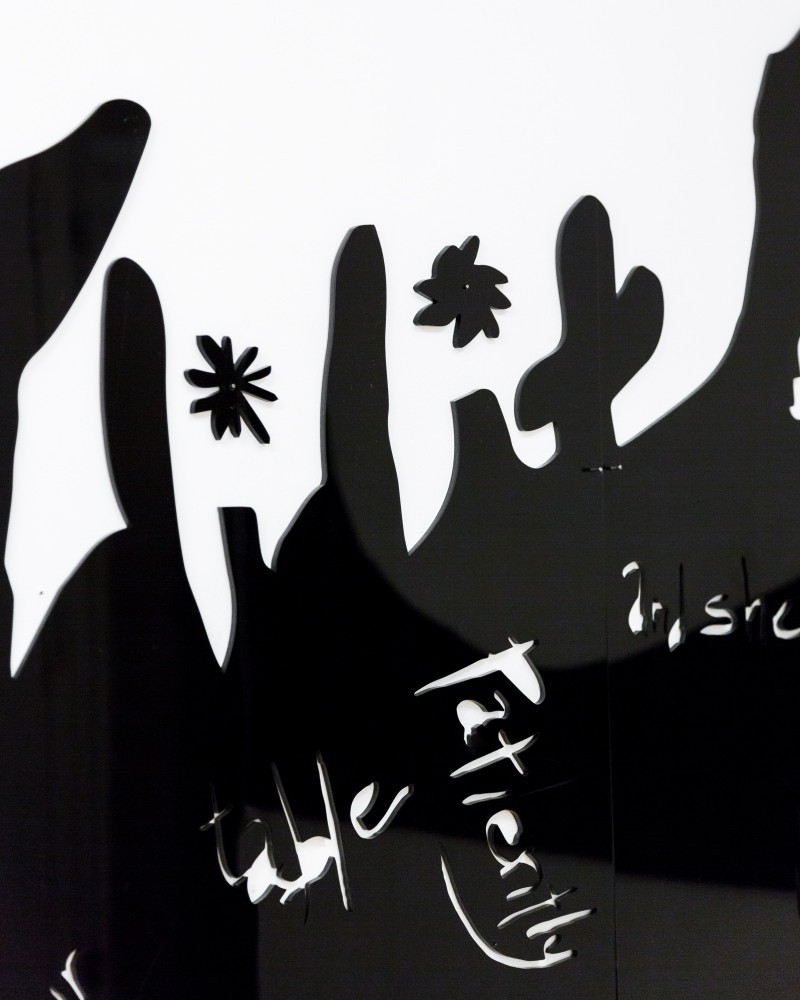

Raque Ford, I did it for myself (2019): acrylic.

Has your mother seen this show?

(Laughs.) This show is not about my mom. It’s very… about us, but not about us. It’s more just a fantasy or it’s a version of what could be. It’s a version of me describing a feeling that was fleeting. Or maybe for one second, I’m like, “Oh, my mother's the devil.” But I don’t completely believe that. I feel like the devil is not always a negative character right now, especially in movies and culture. I feel like (devils) are always sexy, and when you think of female devils, they always seem to become evil against their will.

I remember seeing a show you did at ISCP where Georgia Ford from the movie Cabin in the Sky seemed to occupy a similar space as the maternal character in this piece.

Georgia Ford, she’s not the devil but is called the devil’s daughter. She’s born into it. She’s used to tempt the main character Little Joe into a secular lifestyle but in the end she saves him and repents. There’s also the movie The Witch. The female lead is also not the devil but has to deal with multiple traumatic things that happen to her. Her family is outcast because of her fanatic religious father. She loses her baby sibling to a witch unbeknownst to her. She’s sexualized by her brother and thought of as evil by her father. But the whole time the devil is just pursuing her. In the end she just gives in and joins the witch coven. Everyone believes her to be evil, so she might as well just join in and sell her soul.

-

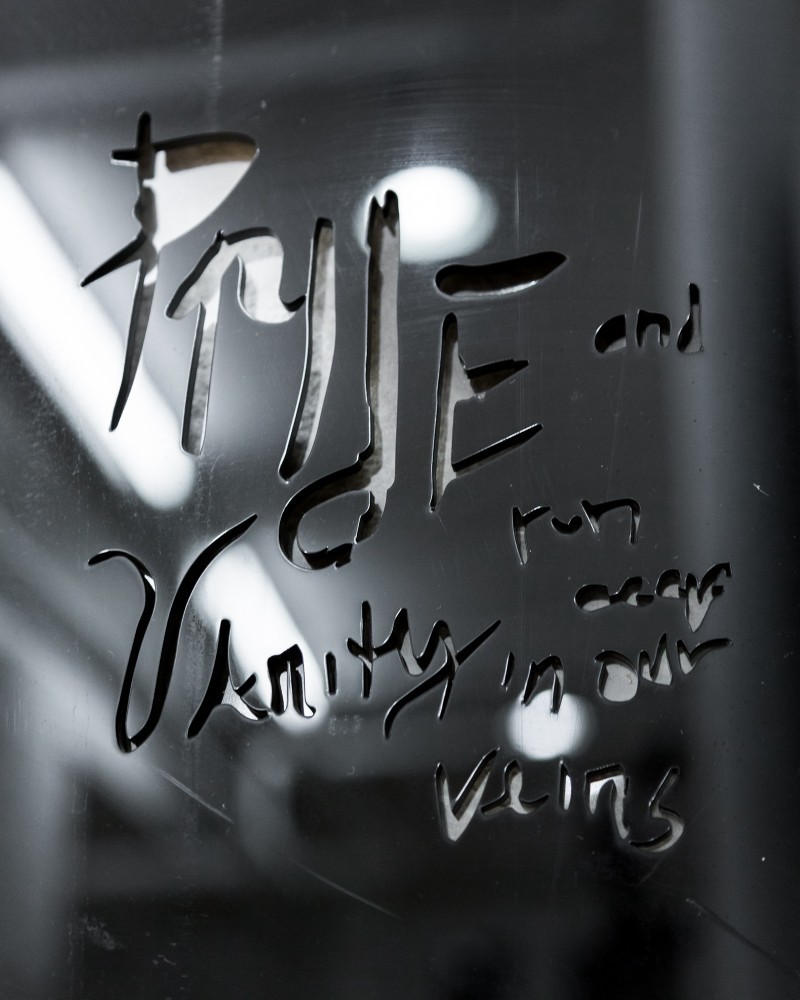

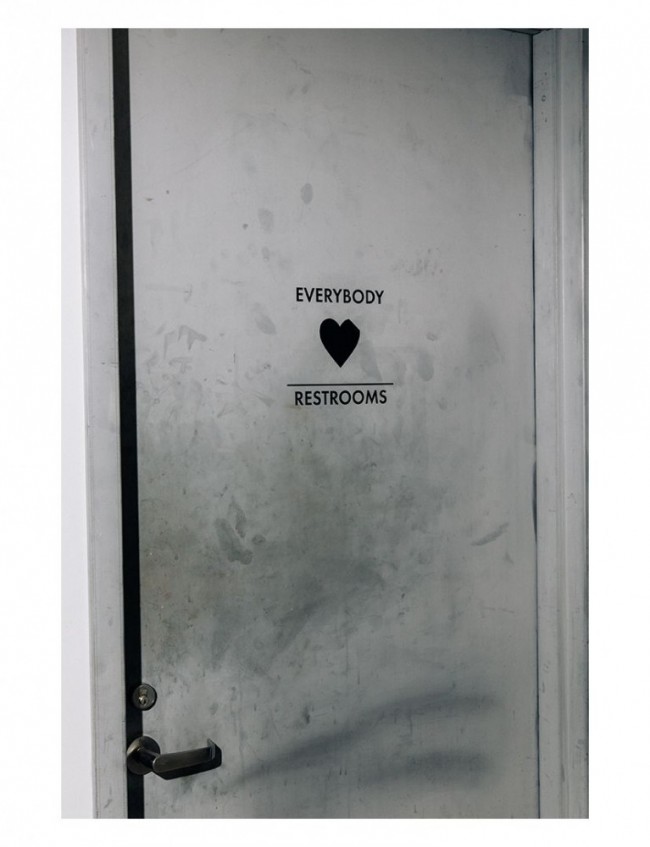

Raque Ford, pride and vanity run deep in our veins (2019): acrylic, spray paint on polypropylene.

-

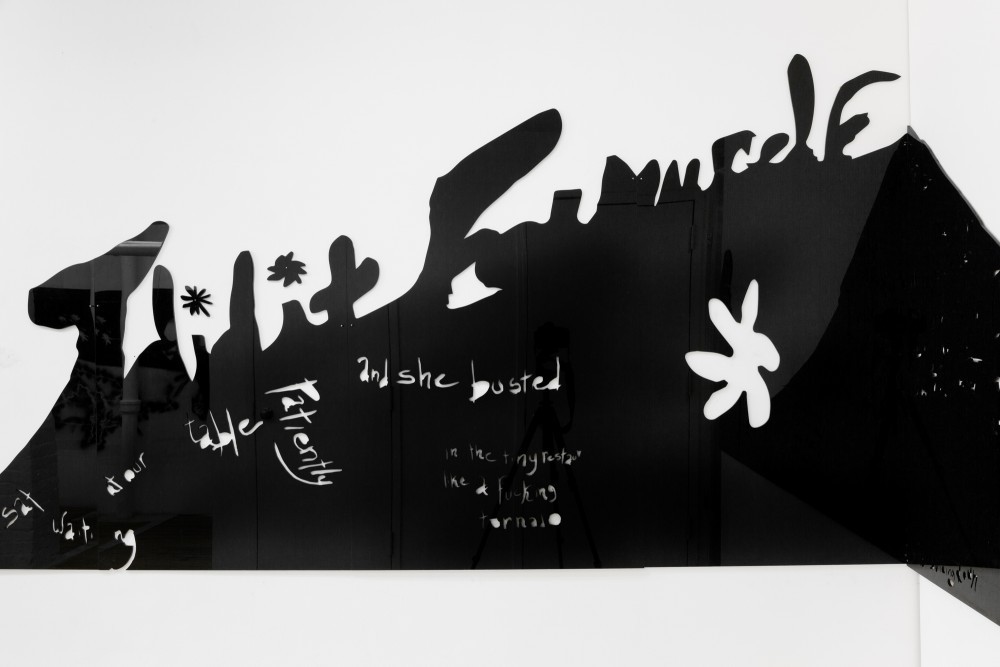

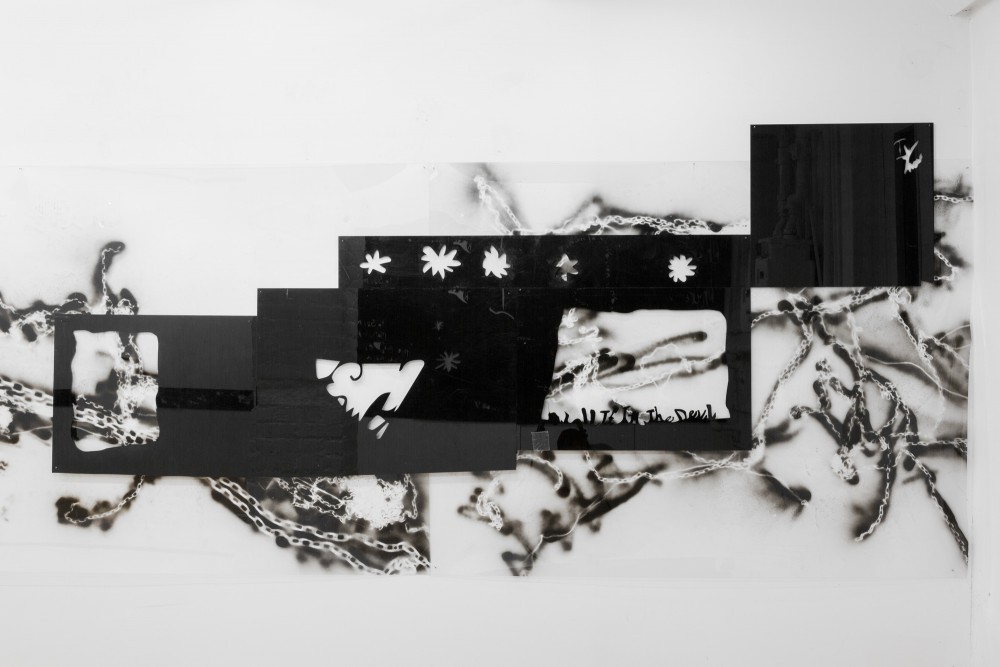

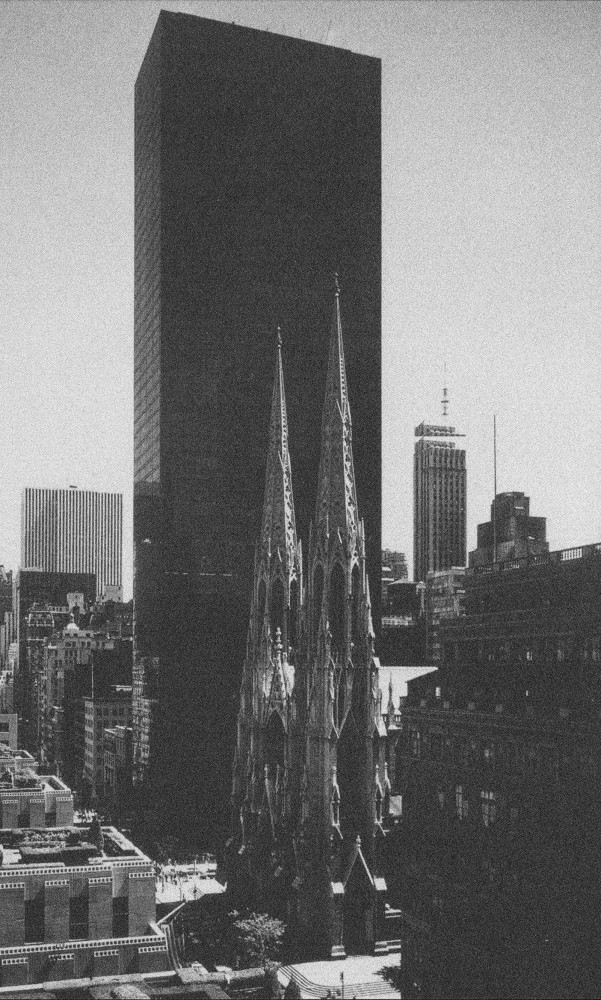

Installation view of Raque Ford, 6 Obsessions at 321 Gallery.

-

Raque Ford, I did it for myself (2019): acrylic.

321 is situated in a single-family home. Do you think about maternal/paternal relationships playing out on the site?

Yeah, that’s funny. I think especially about Daniel (Terna) who runs the gallery and his relationship to his father who lives and has his studio upstairs. My dad also lives really close by, and there is a familiarity there. I grew up sort of familiar with the neighborhood and always associating these buildings with family. My mom has never lived here though. She’s from the South and has always lived close to the South.

The South is the backdrop to this piece?

Yes definitely. “The South is what turned my mother into the devil. Coming here makes me think that this must be where all the evil things happened to her and made her who she is” is etched onto the piece. I always mash it up, so it’s not exactly easy to read. It’s this idea of where not being your choice. Where you lose your agency and you just are who you are. And the South, I guess I always hated it and wanted to get out. I wanted to get out and get back to New York because we lived really close in New Jersey, and I went to school on Governors Island. Later, we moved to Virginia. I’m using the history of the South and escaping it with this piece. New York then becomes this place of freedom.

-

Raque Ford, I did it for myself (2019): acrylic.

-

Raque Ford, pride and vanity run deep in our veins (2019): acrylic, spray paint on polypropylene.

-

Raque Ford, pride and vanity run deep in our veins (2019): acrylic, spray paint on polypropylene.

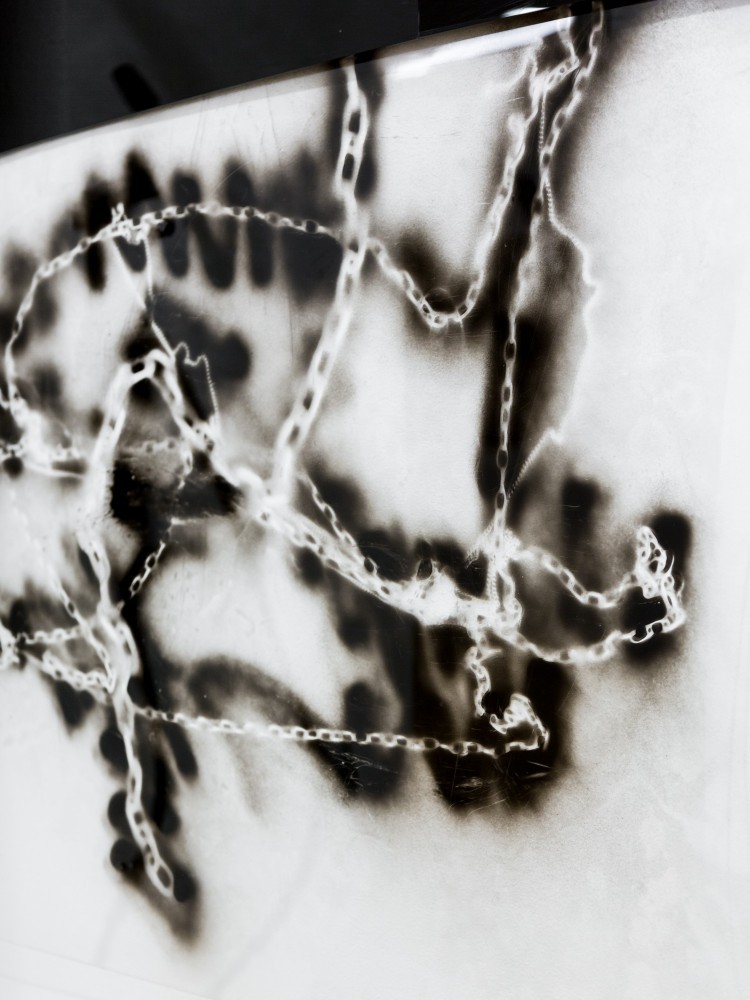

It’s fitting that the piece lives on Plexiglass. Plexiglass is such a New York material.

There’s so much plexiglass in New York that you can find it in the trash. I always use a mixture of found plexiglass and also new pieces as well. I like the scratches on it or imperfections. I often don’t clean it up.

In looking at your work I begin to think of Fluxus-type scenarios. You’ve flipped that around though because the material is of utmost importance.

The material is really important. There’s this level of vanity you can have with it where you see yourself. It’s like a mirror but not — there’s an interruption. Last year I made a dance floor out of the plexiglass. People could dance on the piece and scuff it up, spill drinks on it, and make it dirty.

It’s another kind of language. It also leaves a trace.

The surface traces and writing are equally important. And with the dance floor, you can interact, not in a passive way. Dancing can be so aggressive.

Last year you had a teaching position at Virginia Commonwealth University. Were you living in the South part-time?

Yes, I was teaching at VCU and being back there, I was like, “Maybe I should reconcile my feelings about (the South) or wanting to know. Maybe as I’m getting older, I should reconnect with my history or my roots and try to understand (the place).”

This piece is a huge testament to that. One of the works is 40 feet and the other one?

One’s 40 feet and the other one’s around 30 feet.

Wow, 70 feet in total!

Yes, but I see them as two separate and complementary pieces. I’ve wanted to do a show here for a long time. More and more, I feel like my work always involves some aspect of installation. I wanted to make an installation but I was also thinking about presenting a larger piece — like the dance floor I made last year in San Francisco. I wanted to try and do something different. I also have been thinking about this idea of writing about a mother as a devil figure and the devil’s daughter. And wanting to write this narrative, a longer story, and I thought that if I made a long wrap-around piece, I could work with the narrative, so you could read it around and it could envelop you.

Raque Ford, I did it for myself (2019): acrylic.

This aspect of seeing my reflection and being enveloped calls to mind some themes that run concurrent with minimalism, in tandem with a reference to Fluxus.

Yeah, it’s funny. When you go to art school, everyone’s like, “Okay, Let's teach you about sculpture and minimalists.” I really liked Richard Serra when I was a student. It was just because it was big and metal and impressive. I liked knowing that it could crush me or something. The work had this aggressive presence.

I think I always wanted to make sculpture, but I was a painter. And then, when I was making (sculptural) work obviously, those things influenced me, but it doesn't make sense for me because I'm just not those men like Robert Smithson and Richard Serra. A majority of their concerns are not my concerns or their concerns don't actually relate to me. I thought it was funny that I liked them, but then I thought about how to use the qualities I gravitated towards to make my points heard. That's the interjection of being a woman of color and learning these ways of making sculpture. I’m taking these simple gestures and making them more complicated. I want to have their energy, their aggressive scale and material — I want to have a ton of it. I’m taking all of that and making it my own.

Do you think you’re removing their sense of individual ego?

I want to operate inside of that ego, the male ego. I don’t know. I like making big work. I would make my work even larger if I had the space and the income and the budget. The way I'm using text and where that text is being generated from is intimate, but also large and aggressive. The other day I was thinking, “Oh okay, so I did this piece in order to continue writing the text and finish this narrative about a mother from the South.” But then I was like, “You know what I should write? I want to write a text in a male perspective.”

That's a great idea.

Maybe I should just write what I don’t know and just write a male character. I feel like I tried in the past when I wrote this Beyoncé fan fiction where the main character talks about how she looks like Beyoncé but she thinks she’s more of a Solange but deep down she’s really a Jay-Z, a strong man. Maybe it’s a weird fantasy (to write a male character) but I think it’s more interesting in my voice. I was thinking that should be the next thing.

Text by Paul Kopkau.

Images courtesy of the artist and 321 Gallery.

Raque Ford, 6 Obsessions at Brooklyn's 321 Gallery runs until July 13, 2019.

Paul Kopkau (*1982 Monroe, Michigan) is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, New York. He is co-founder of the group “Yemenwed,” a multi-disciplinary collective. His work has been included in exhibitions at Company gallery, The Swiss Institute, 321 Gallery, The Perez Art Museum Miami, Rutgers University, and elsewhere.