HOT SPOTS: Accessibility And Design From Gender-Neutral Bathroom To Anti-Homeless Architecture

The politicization of the human body is physically manifested in our built environment. Issues of accessibility, gendered space, and abortion clinics, speak volumes about what bodies are valued in this country, and how this value is expressed through architecture. PIN–UP presents four case studies.

GENDER-NEUTRAL BATHROOMS

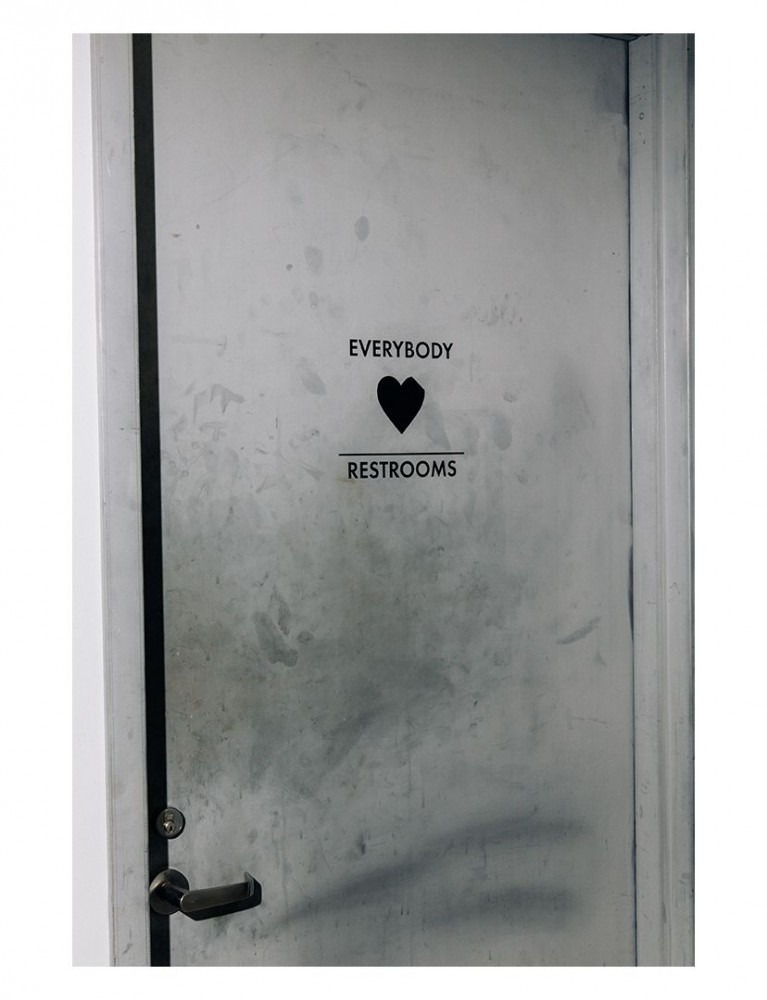

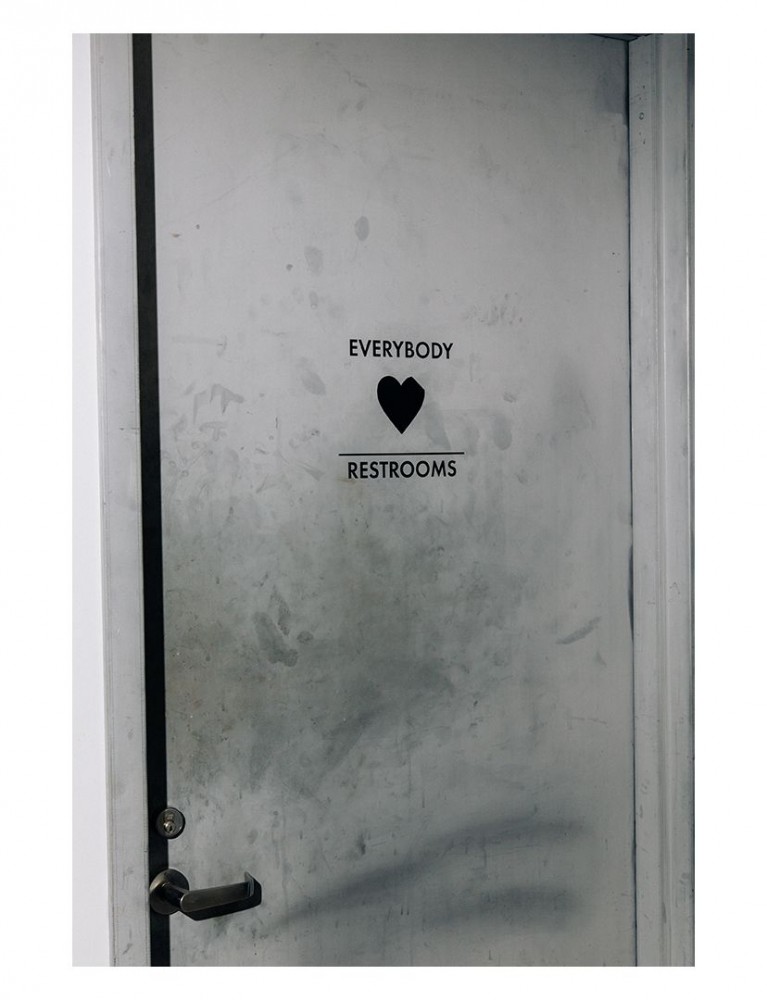

Restrooms at the Performance Space New York, photographed by Daniel Terna for PIN–UP.

As the famous bathroom scene in Kenneth Anger’s 1947 Fireworks and Klymaxx’s 80s hit “Meeting in the Ladies Room” can attest, what goes on in the most private of public spaces can be both political and interpersonal (and fabulous). Bathrooms have been battlegrounds for gender, sexuality, and hygiene wars for millennia. In recent years, though, as transgender citizens and their allies work to dismantle roadblocks to their full participation in society, the very idea of what a bathroom should be has come into question. Should they, as the right would have it, be segregated spaces that at once reinforce the gender binary and “protect” cis women from male rapists? Or should they be structures that allow anyone, regardless of genitalia or expression, a place to fulfill the demands of bodily functions in relative peace? While we wait to see if courts and governments will affirm the basic dignity of people regardless of anatomy, architects and designers are working through how “male” (and “female”) urinals might commingle with stalls, or vanish entirely; whether sinks fare better in individual stalls or as troughs in zones removed from the action; and which graphic-design solutions will best direct the crowds. Fittingly, given the performative nature of gender itself, Performance Space New York solved the problem with a simple welcome sign “EVERYBODY,” created by artist Sarah Ortmeyer with designer Erin Knutson.

ACCESSIBILITY RAMPS

Accessibility ramp on Fulton Street, Brooklyn, photographed by Daniel Terna for PIN–UP.

It says something about the way America views its citizens with disabilities that it took a federal law — and several-hundred years — to decide that, should one choose to construct a new building, most everyone in its community should actually be able to enter and access it. Thirty years on, the Americans with Disabilities Act has gone a distance to make the built environment a bit more accessible. All too often this has meant slapping a ramp onto some building’s back or side (not unlike the one pictured), though rightly-heralded projects like the elegant switchbacks of Weiss/Manfredi’s 2019 Robert W. Wilson Overlook in Brooklyn Botanic Garden offer proof, should one require any, that accessibility and aesthetics are not mutually exclusive. Real progress will come when we stop thinking about accessibility as an obstacle to architecture and see it instead as the reason architecture exists.

ANTI-HOMELESS ARCHITECTURE

Anti-homeless spikes on 10th Avenue and 21st Street in New York City, photographed by Daniel Terna for PIN–UP.

The decision whether to spend time in public space this year is dizzyingly complex: the danger of being out in a crowd during an airborne pandemic versus the mental-health ramifications of extended isolation; the threat of contagion versus the equally mortal threat of allowing police violence to continue unprotested; the possible exposure of restaurant and bar workers to infection versus the industry’s possible mass extinction if nobody patronizes them. For those experiencing homelessness, these decisions are moot — public space is the only housing society offers them. This makes recent innovations in what’s known as “hostile architecture” especially dispiriting. Strips of metal teeth line low walls across cities, ensuring that the unhoused (or anyone else) cannot rest upon them. Public plazas boast bolts on ledges, and rows of spikes adorn windowsills (pictured). What seating exists is often at an awkward pitch, and benches are carved into measly chunks, barely wide enough to function. Unsatisfied with chasing the unhoused — who tend to be disproportionately Black, Latinx, transgender, and queer — the residents of L.A.’s Reynier Village, decided to become amateur hostile designers themselves: during a record-breaking heatwave and ongoing pandemic, they filled an underpass where several locals had lived with boulders, achieving an ugly combination of NIMBY and DIY.

HEALTHCARE CLINIC GUIDELINES

Planned Parenthood in Los Angeles, photographed by Daniel Terna for PIN–UP.

Forced-birth activists across the United States fight against reproductive autonomy with legal proceedings, intimidation, and even violence. Recently they’ve found a new tool in architecture. Targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP) seeks to reclassify healthcare clinics like Planned Parenthood (their Bixby Health Center in Los Angeles pictured) as ambulatory surgical centers, a change of identity that mandates pricy, complex, and medically unnecessary alterations of anything from the width of the hallway (to accommodate gurneys which are vanishingly necessary for abortion services) to HVAC systems and colors for paint. The Supreme Court has struck down a pair of TRAP laws, for now, but the weaponization of building codes and shuttering of facilities nationwide warns us that, at the moment, the built environment is increasingly unhealthy.

Text by Jesse Dorris.

Photographed in Brooklyn, New York, and Los Angeles by Daniel Terna for PIN–UP.

A version of this article was originally published in PIN–UP 29.