BAGHDAD DESERTED: Tales From A City That No LoNger Exists

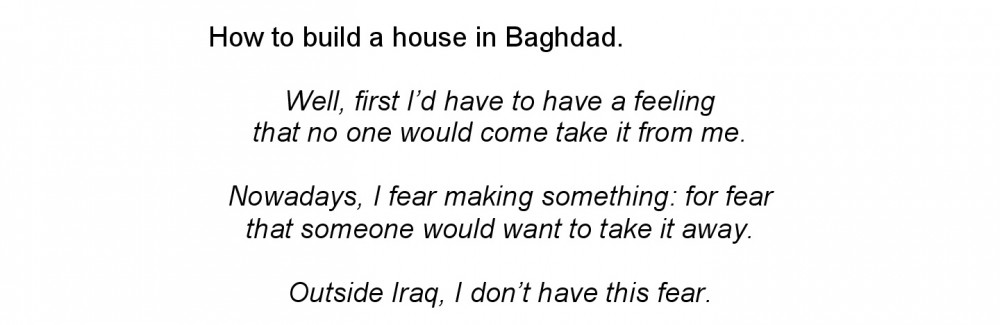

These are the words of Nedim Kufi, whom I visited in his studio in Amman, Jordan, when we were both based there in the spring of 2017. Kufi –– an Iraqi-born visual artist who seems as comfortable cleanly snipping himself out of his past with Photoshop as he does getting his hands dirty to create massive cement-, henna-, and paint-covered canvases that flake to accrue a jarring lisp of symmetry just-off enough to feel real –– had returned to what had once been a purgatory en route to refuge in Holland. He had expected Dutch life would be Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe on a loop, and instead found his work confined to “refugee status” by arts institutions long after he had settled in the Netherlands. Kufi wanted to work in a place where, swamped in his identity, he could breathe without worrying about his gills being gawked at.

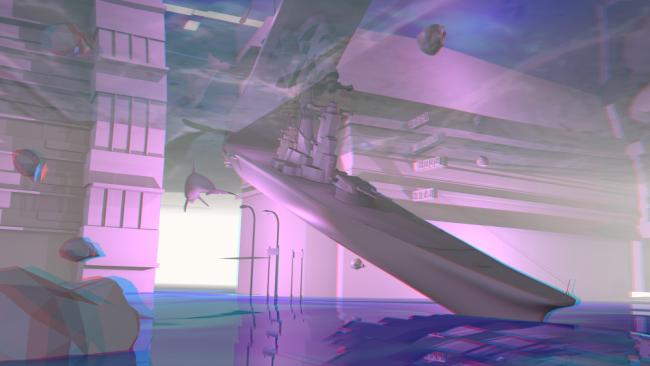

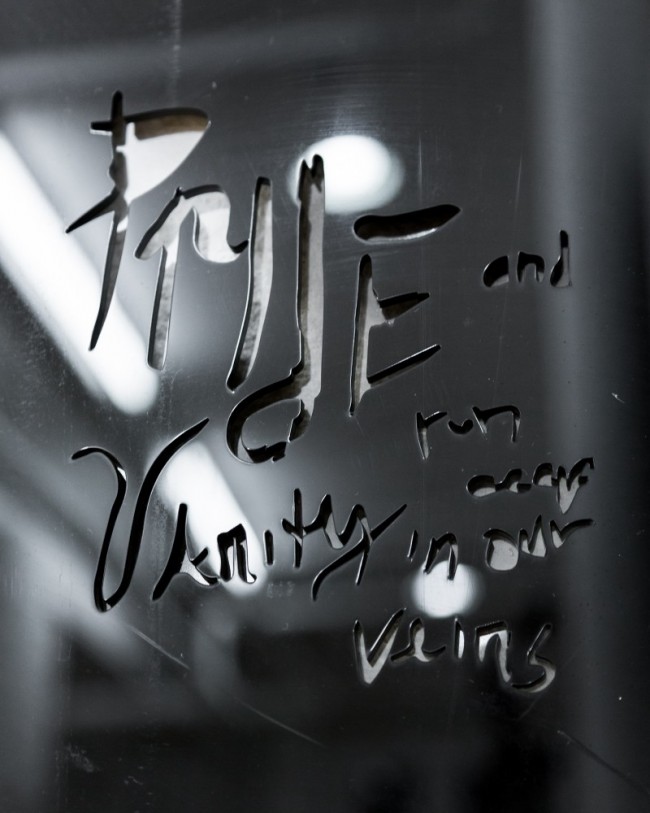

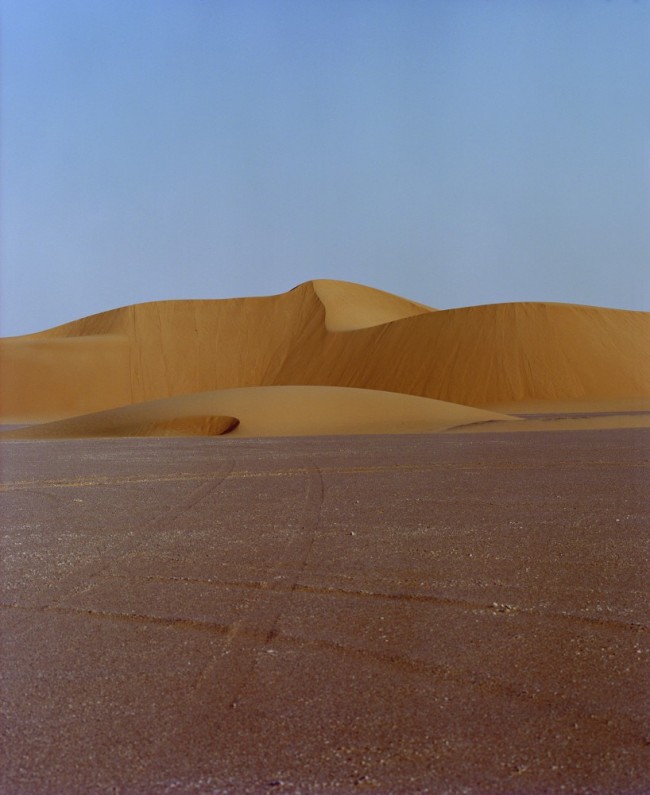

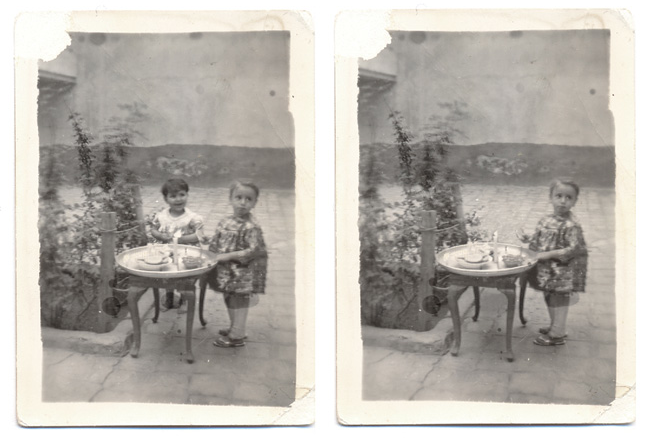

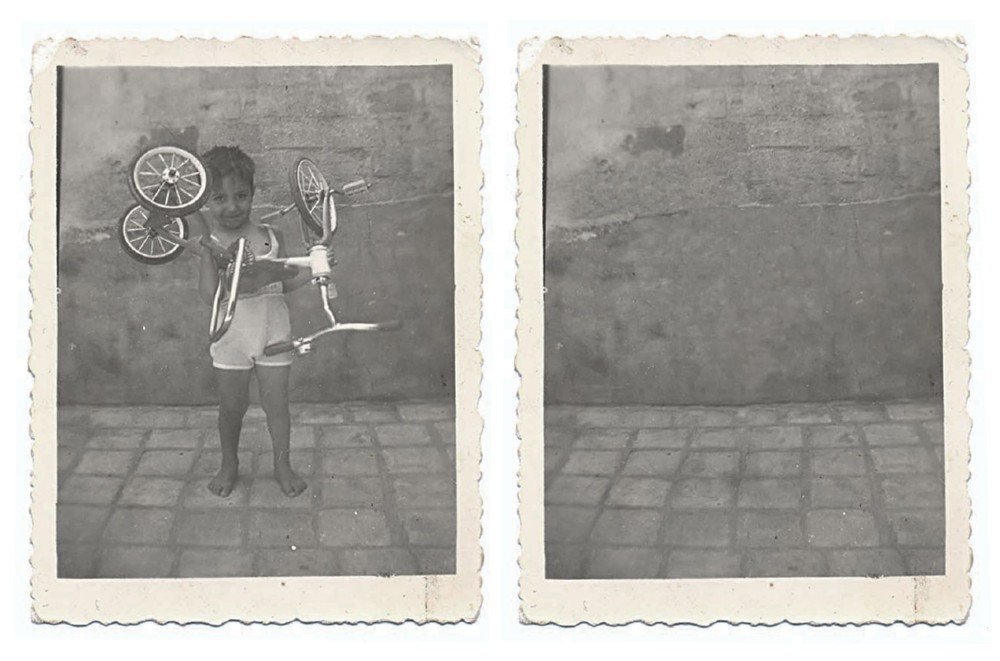

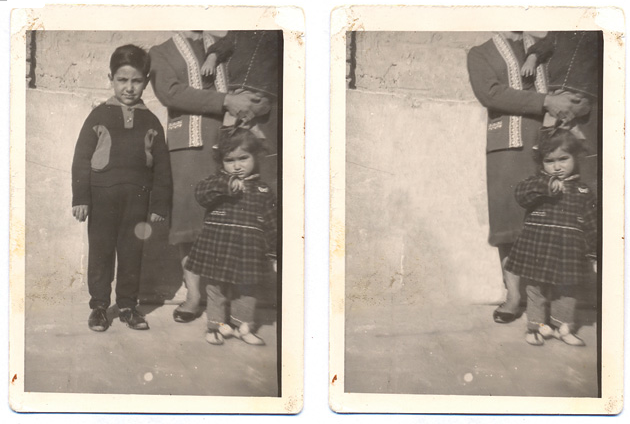

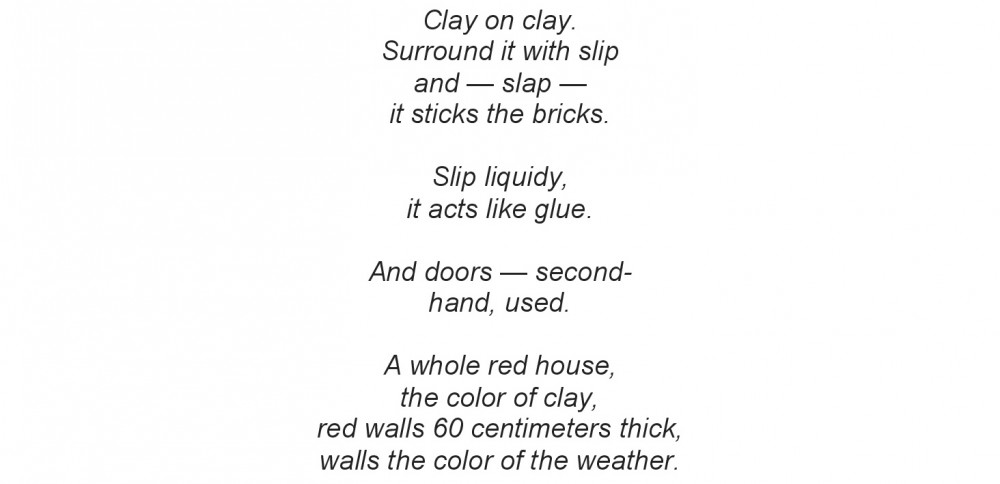

Nedim Kufi, Absence (2008); Digital diptych. Courtesy the artist.

We quickly developed a close friendship –– the shifty kind formed between people who are delirious to have found a common language but are still not really home, and –– as became increasingly clear over my 14 months in Amman –– perhaps never will be. I had moved to Jordan to interview members of the Iraqi diaspora about their memories of life and love in mid-20th-century Baghdad with the goal of creating a comprehensive psychogeography of the city, an emotional cartography of a historical sweet spot just before the decades of conflict that have defined Iraq throughout my entire life. We think of history as flowing in one direction: past to present, east to west. A building goes up; we can’t watch it live-rewind brick by brick. In order to talk to people about their pasts, the buildings that defined their lives, I had to sit with them in their present, walk backwards. Home was increasingly defined in the negative: you understand what it is by what it isn’t. It’s different than learning to appreciate something once it’s gone: it’s witnessing the dismantling of meaning before your eyes.

Nedim Kufi, Absence (2008); Digital diptych. Courtesy the artist.

Kufi’s fear of home simply being taken away was not a fanciful attempt to attach words to some lump in the gut. Sometimes a house does desert you. Laila Pio, the first woman carpet seller in Baghdad (she learned the trade by way of travels with her father, often cutting school to accompany him as he traded for antiquities) stiltedly related what happened to her house during the decade of sanctions following the first gulf war. “For instance, for us, our house –– the laundry. When we hung it outside, it was stolen. The tires of our car, the gas canister, were stolen.” The instability of daily reality becomes most apparent in the mundane, in the bits and pieces that are simply a part of things, until the thingness of anything can no longer be taken for granted. A closet becomes missing laundry. Once, an automobile was parked in a driveway. Now tire-less and without juice, it moves past its function, beyond recognition. A spot of loss in place of rest.

Nedim Kufi, Absence (2008); Digital diptych. Courtesy the artist.

Pio closed her eyes and repeated one word like a mantra to describe the house she shared with her husband in al-Slaikh, a northern-Baghdad suburb situated on the banks of the River Tigris: “Nakhal, nakhal, nakhal, nakhal.” (Palms, palms, palms, palms.) She began to wave, treelike, as she reverberated the word. A look of calm came over her face. The names of fruit slowly followed. Fig. Clementine. Grape. Sweet lemon. Naranj. Pomegranate. Apple. I spoke with over 40 Iraqis living in Amman, and not one account of home was complete without a description of the garden and what grew in it.

Not only the house, but the root of the house –– water, the essential ingredient in concrete slabs and clay bricks, in the gardens that serve as visible touchstones of care in the home –– has been rerouted. In 2018, the Daryan Dam was completed in Iran, strangling the source of 30 percent of the Tigris’s water, as well as of hydroelectricity dating back to the 1950s, when Iraq’s development dreams included Swiss-style tourist chalets powered by water-driven turbines. Turkey has constructed five dams on the Tigris, with plans to build three more. Pio would hire a boat to cross the river and cart her groceries home. Now, in the midst of an ongoing six-year drought, it is possible to walk across the river, and not like a prophet. Some sections are bone dry.

Nedim Kufi, Absence (2008); Digital diptych. Courtesy the artist.

Without a garden, now that it’s dried-out and gutted, what is a house? In wartime, a home becomes an inconsistent filter, letting in dust and offering little protection.

Land has stayed put at its point of origin, or tried to. Mud and clay don’t move where the wind blows, though dust does. Water is inseparable from the imagination of the home. The most intimate form of architecture has garnered little attention in reporting throughout Iraq’s history, let alone during the vagaries of Desert Storm. Yet home is what fixes people to a place.

Pio was a recent Iraqi expat in Jordan, having held out as long as she could in her country, until it became clear that those who were sticking around were mostly waiting to die. A story I was familiar with through my khala –– my mother’s eldest sister –– who fretted when we met for the first time in Yalova, Turkey. She was in her 80s, and accompanied by her daughter Neshwa who fed me dates from the palm tree in their backyard in Iraq. They were sticky-sweet, more honey than fruit. Eating them I was simultaneously eager for a taste of Baghdad and sick with the thought of what chemicals had leached into the soil. Of the dozen date palms in their garden, five were still bearing fruit, Neshwa reported. “And how are your chickens doing?” my mother asked. Khala was anxious to get home, and let it be known. We turned on the TV for her –– news of Baghdad, war news.

Nedim Kufi, Absence (2008); Digital diptych. Courtesy the artist.

Iraqis spread round the world like weather, moved by definite pressures as well as hot air spun into a blunt force. The numbers of the Iraqi diaspora are massive but difficult to measure –– not to mention internally displaced people, and those sitting with the fact that their home has gotten up and walked away due to theft or the increasing political and emotional vagaries of sectarianism, which has slashed away trust and eroded neighborhood relationships. When surroundings become foreign and you haven’t left, you’re in a foreign territory anyway.

Noor Al-Samarrai is a New York-based poet and performer. As a Fulbright Creative Arts Grantee in Amman, Jordan, she collected oral histories for an in-progress book about Baghdad's psychogeography.

Text by Noor Al-Samarrai.

All artwork by Nedim Kufi.