RETAIL APOCALYPSE: BEST Big Box Stores Designed by James Wines Of SITE

Double page excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

Designing retail spaces, especially fashion retail spaces, follows a different set of rules to other forms of architecture. They're often ephemeral in nature and, although commercial, do not always have clear goals or functions. According to Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen, directors of exhibitions at ETH Zürich and the authors of a new book Retail Apocalypse, these and other conditions make retail architecture and enduringly Postmodern endeavor and experience. The world of fashion retail also harbors paradoxes that reflect broader quandaries of how we've consumed culture throughout the past century, especially from the 1970s until now, in a post-pandemic world of the 21st century. For their book Fischli and Olsen gathered a group of architects, artists, designers, theorists, and general cultural observers with a relevant connection to retail, such as architect and SITE co-founder James Wines.

-

Excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

-

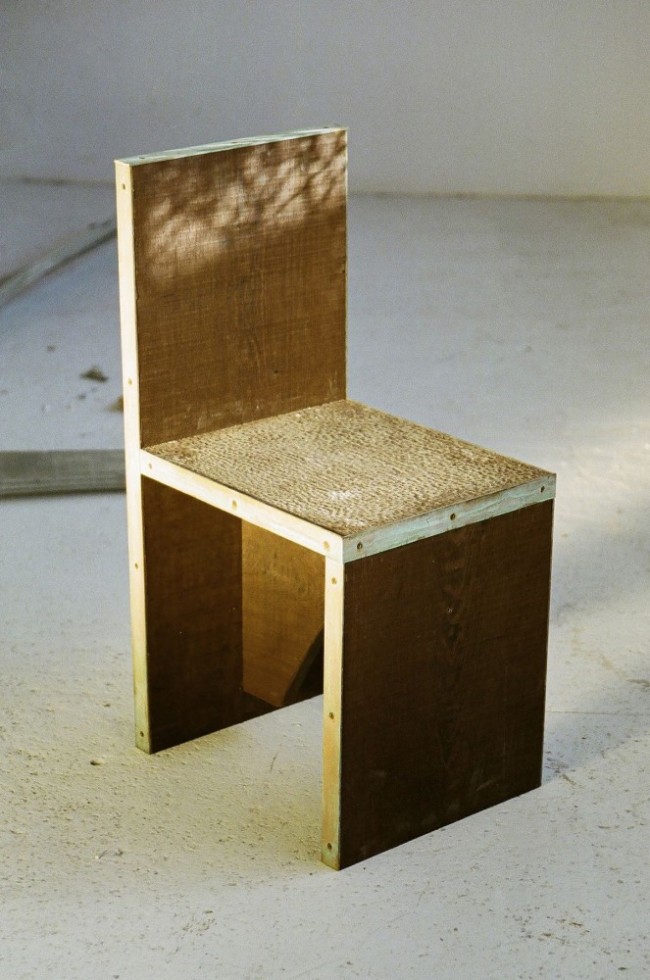

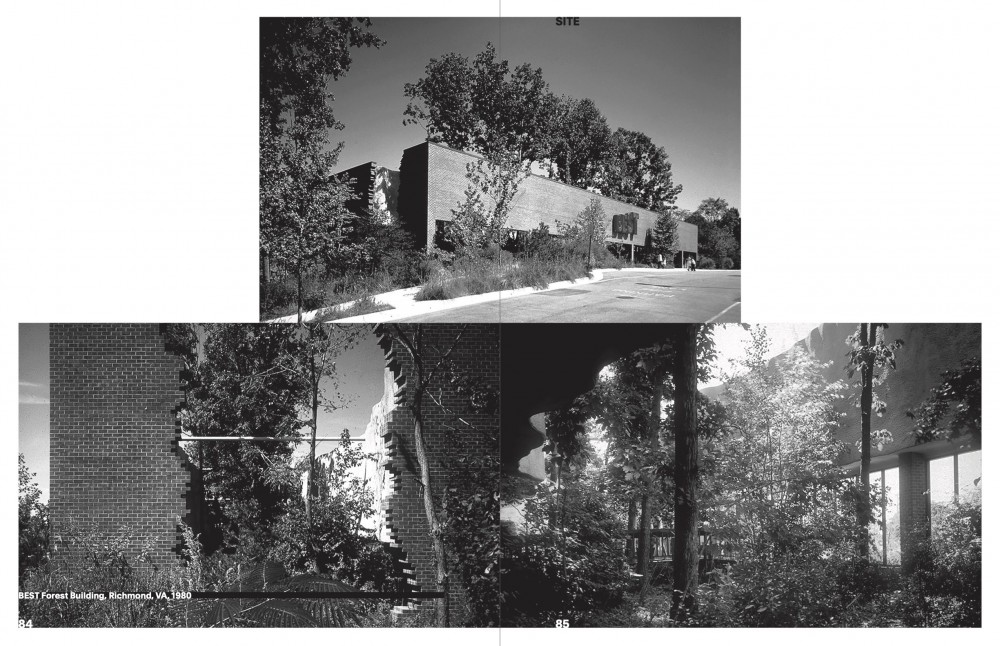

BEST Product Company, Inc. big-box store by SITE, United States 1975–84. Photography © SITE.

In 1972, New York City-based architecture and environmental arts studio SITE was commissioned by BEST Products Company to design a series of nine “big box” shopping centers across the US. These self-referential, concept-driven stores have gained legendary status in retail design and typify a rather cheeky, ruin-obsessed moment in architectural Postmodernism. Wines recounts how the unconventional project came to be as well as how it foreshadowed today’s retail apocalypse.

Double page excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen: You’ve described the BEST stores as “subject matter for art,” rather than conventional architecture. Could you tell us about this approach as well how the company agreed to this experimental strategy of yours?

James Wines: It was a huge advantage that the clients Sydney and Frances Lewis were major art collectors and really understood art. It wasn’t a battle, although many couldn’t understand how they ever agreed to construct buildings that were basically critical overviews of this whole idea of the big box shopping center. At that time, there were already big box shopping malls, usually located along highways, which we treated as found objects or as existing situations just waiting for assault. People accepted the always-same signature of this architecture, its services and its work. Therefore, we found it interesting to invert this meaning, to play with it by including both the environment and the audience as a physical part of the space. We wanted to turn the stores into highway art, because we have always said that it gives us the biggest pleasure to place art where you least expect it.

In the early 1970s, at the end of the Pop Art movement, I was part of extremely fruitful dialogues within environmental art in the USA. In my opinion, this was the first time that artists really dealt with architectural issues. My long residency in Italy was also very productive, as I was in exchange with the radical architects of the Milanese and Florentine design movement, who completely merged art and architecture. Unlike in Italy, in New York, there were thousands of building façades and streets in public space with which one would never have a dialogue: there was nothing to think about, nothing to talk about. I considered it my mission to see what can be done to make the environment more participatory and to help people think differently. We like to call these participatory invitations trigger mechanisms or trigger items.

BEST Product Company, Inc. big-box store by SITE, United States 1975–84. Photography © SITE.

Looking at this project today, it seems as if you have foreseen today’s retail apocalypse. What are your thoughts on the current state of brick-and-mortar retail?

In a peculiar way, the many writers who criticized and ridiculed this type of building also anticipated the fact that computers were going to take over the retail trade and wipe it out almost completely. But the funny thing is that retail is coming back again as a physical experience: now they are building all kinds of shopping malls as an attempt to make the stores more interesting and appealing to get people in the door. In fact, there are now philosophers of retail who say that the retail space is a place where people experience the product. Getting people to experience and participate was also an essential part of what got SITE going originally.

BEST Product Company, Inc. big-box store by SITE, United States 1975–84. Photography © SITE.

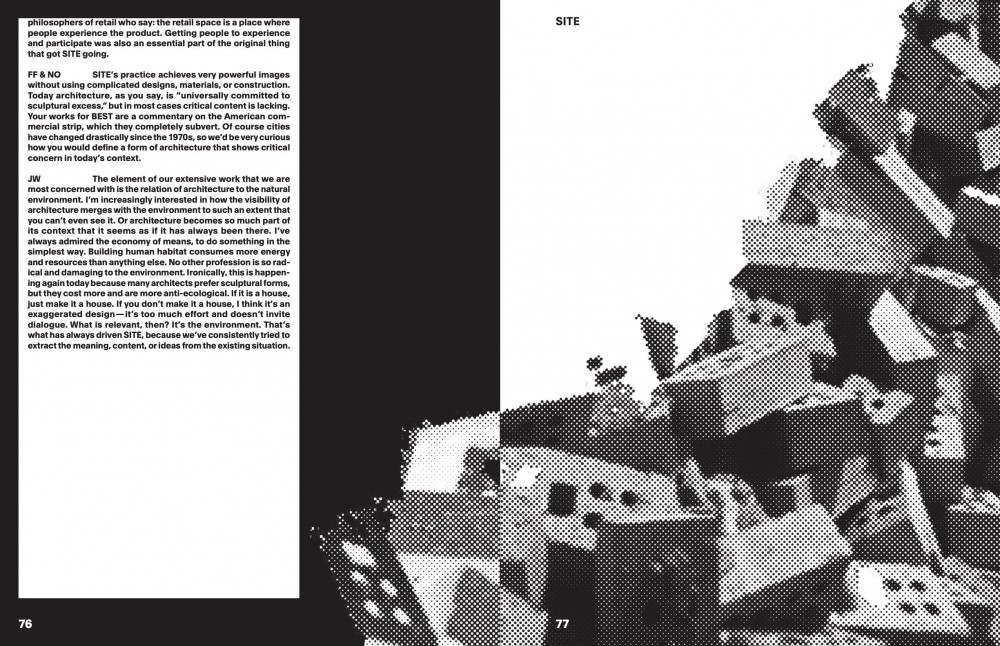

SITE’s practice achieves very powerful images without using complicated designs, material, or construction. You’ve said that architecture today is “universally committed to sculptural excess,” but in most cases critical content is lacking. How would you define a form of architecture that has a critical concern for today’s context?

The element of our extensive work that we are most concerned with is the relation of architecture to the natural environment. I am increasingly interested in how the visibility of architecture merges with the environment to such an extent that you can't even see it. Or architecture becomes so much a part of its context that it seems as if it has always been there. I've always admired the economy of means, to do something in the simplest way. Building human habitat consumes more energy and resources than anything else. There is no other profession that damages the environment as radically as buildings. Ironically, this is happening again today because many architects prefer sculptural forms, but they cost more and are more anti-ecological. If it is a house, just make it a house. If you don't make it a house, I think it's an exaggerated design — it's too much effort and doesn't invite dialogue. What is relevant, then? It's the environment. That's what has always driven SITE because we've consistently tried to extract the meaning, content, or ideas from the existing situation.

The new book Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021), edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper, can be ordered here. (Special support by Artek.)

Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen are directors of exhibitions at the Institute of the History and Theory of Architecture (gta) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH). Together they’ve curated numerous international exhibitions on art and architecture including Readymades Belong to Everyone at the Swiss Institute in New York, Trix & Robert Haussmann at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin and the Nottingham Contemporary, and Inside Outside/Petra Blaisse — A Retrospective at Triennale Milano (all 2018).

A version of this interview appeared in PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020. Additional editing and writing by Akiva Blander.

Photography © SITE.