RETAIL APOCALYPSE: Chilean Architect Smiljan Radić’s Concepts For Céline And Alexander McQueen

Designing retail spaces, especially fashion retail spaces, follows a different set of rules to other forms of architecture. They're often ephemeral in nature and, although commercial, do not always have clear goals or functions. According to Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen, directors of exhibitions at ETH Zürich and the authors of a new book Retail Apocalypse, these and other conditions make retail architecture and enduringly Postmodern endeavor and experience. The world of fashion retail also harbors paradoxes that reflect broader quandaries of how we've consumed culture throughout the past century, especially from the 1970s until now, in a post-pandemic world of the 21st century. For their book Fischli and Olsen gathered a group of architects, artists, designers, theorists, and general cultural observers with a relevant connection to retail, such as Chilean architect Smiljan Radić and his work for Céline under Phoebe Philo and Alexander McQueen.

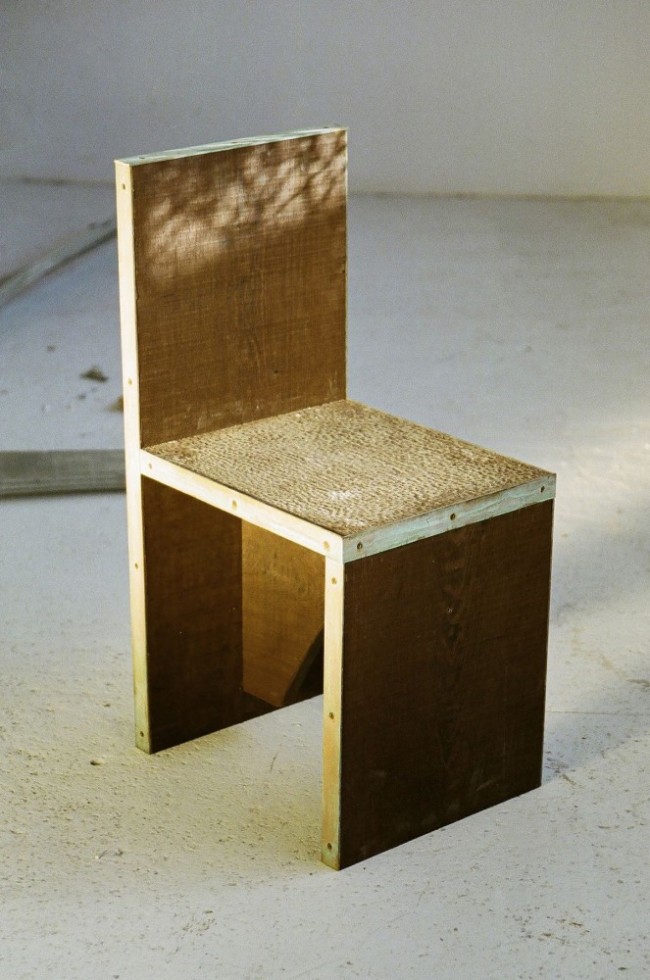

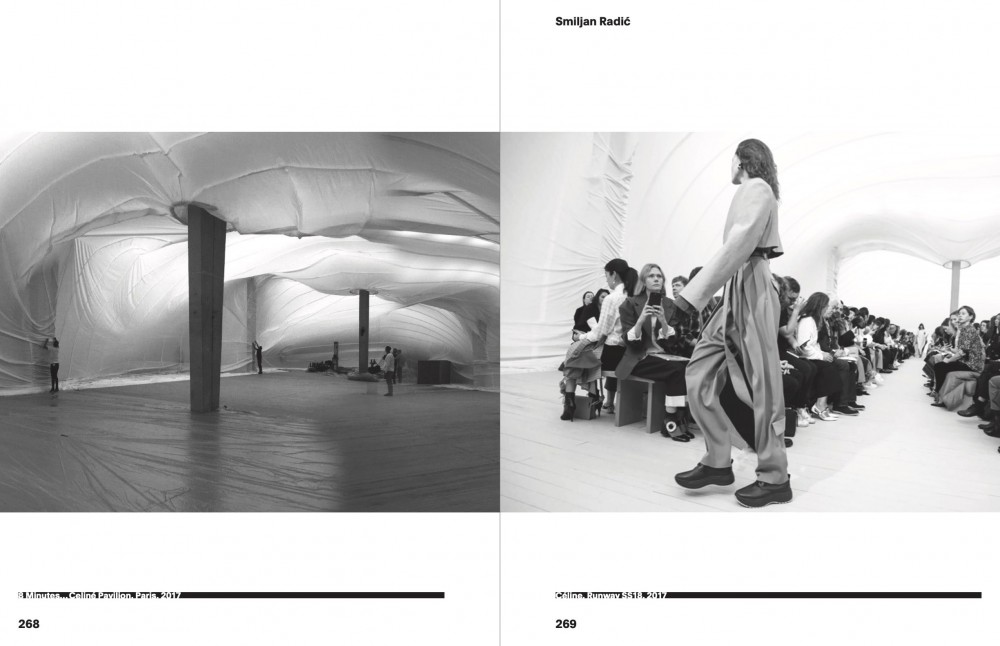

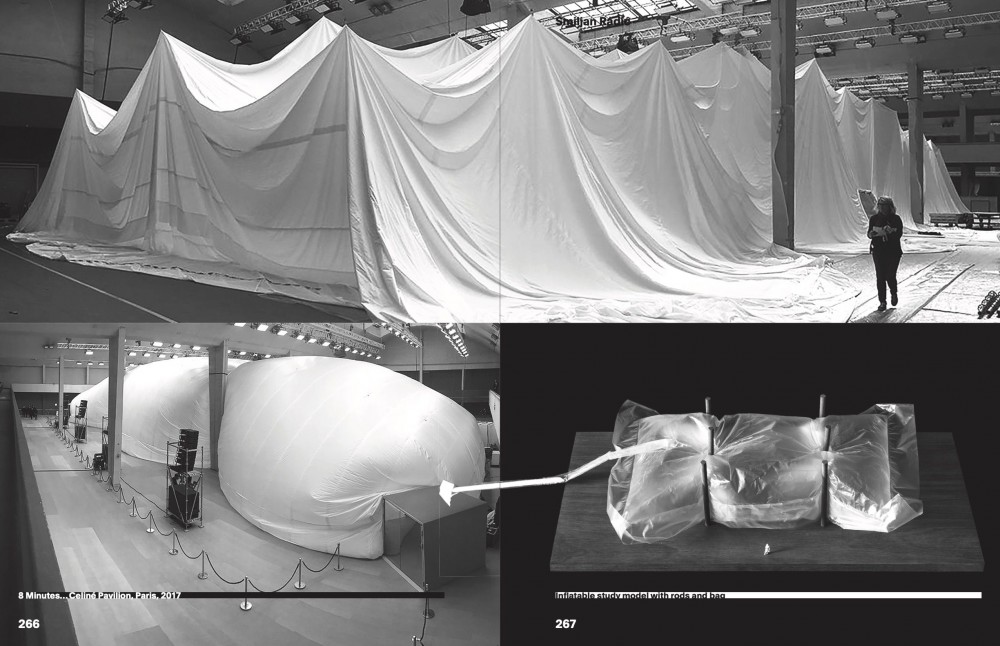

Installation by Smiljan Radić for Céline fashion show, Paris 2017. Photography courtesy Smiljan Radić.

Radić's eclectic portfolio is distinguished by a fascination with primordial forms; indeed, his egg-like Serpentine Gallery Pavilion helped propel him to international repute in 2014, and his more recent retail work is no exception. The massive, temporary inflatable he created to stage Céline’s Spring Summer 2018 show (Philo’s last) suggests a womb-like envelope. The three-story Alexander McQueen London flagship Radić designed in 2019 (it opened in 2020) features rocky boulders and sinuous wood sculptures. (See the documentary here.)

Excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen: You recently inaugurated the Alexander McQueen flagship in London, a total environment that includes numerous natural rocks, some with inlaid, fake-fur elements. Could you tell us about your approach?

Smiljan Radić: In these types of projects, it’s hard to define elements as “real” or “fake.” At the Old Bond Street Store, everything is staged and it’s about inventing a vocabulary that can stage a scene or environment in any part of the world. Any given piece — a stone, a mannequin, a fitting room — begins to support this when it becomes ephemerally indispensable, like when the supposedly decorative becomes structural. In our project, art, architecture, and fashion design occupy the same hybrid space, a type of “domestic labyrinth,” which through the installation of a series of objects within the space seems put together in a confusing manner. We left the walls and the floor space open to provide a certain spatial freedom, so that each place could be configured differently according to each site.

Installation by Smiljan Radić for Céline fashion show, Paris 2017. Photography courtesy Smiljan Radić.

Throughout history retail spaces have offered an opportunity for architectural novelty. There are so many examples from Frederick Kiesler’s book **Art Applied to the Store to Herzog de Meuron’s Prada store in Tokyo. But what about today? What are your thoughts on the current state of retail architecture?

**I don’t really have a global opinion on the subject. I don’t really know of many examples and I’m only interested in this topic as a case in point, not as a speciality. What I can say is that retail spaces are generally non-spaces with established codes, regardless of the architect. The layout and the way in which products are displayed are more or less the same, and the only thing that uncomfortably changes from one year to the next are the materials.

-

Excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

-

Excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

You created an inflatable for Phoebe Philo’s last Céline show. An enormous textile blob was blown up for the brief catwalk. Could you tell us about this project?

The show lasted eight minutes and was held inside some tennis courts on the outskirts of Paris — a hostile interior that we needed to make disappear. Because of this, temporarily and quickly inflating a space as if it were a performance piece from the '60s seemed like a good strategy. We decided on a simple giant parachute-nylon bag. As it filled with air and reached its actual size, it allowed the building’s structure to mold to it. The fabric we chose, which looked like a thick silk, gave the whole thing a sensual, textured appearance. In that slow-moving light bag, 900 people enjoyed an elegant and friendly show.

You collect drawings, books, and posters by radical designers. What are some projects that, for you, are relevant to the history of retail architecture?

I think that the ephemeral aspect of this type of architecture can be really useful; retail spaces become obsolete, with luck, in eight to ten years, and they cease to exist beyond a season. Architecture deemed radical in the '60s could be useful, formally speaking, but those movements had a political context that cannot be overlooked. Many of them sought to abolish objects and consumerism. This would completely alienate our retail projects.

Excerpted from Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021) edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper.

Retail seems to be in a global crisis but it persists as an important realm for architects. One could argue that a retail store is a kind of ruin from the beginning. Do you think this is part of its attraction for architects?

In my country, every project has this condition of non-permanence or premature ruin. For us, it is not a foreign concept; on the contrary, it’s the initial premise. So, when we approach the European market, one is strangely obligated to think about permanence or, in a similar vein, the large quantities of energy deployed to produce something. I think the degrees of instability in our planet should make us rethink the initial architectural conditions on a case-by-case basis. But I also think that architecture will become more rigid, seeking construction that will survive everything.

The new book Retail Apocalypse (gta, 2021), edited by Fredi Fischli, Niels Olsen, and Adam Jasper, can be ordered here. (Special support by Artek.)

Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen are directors of exhibitions at the Institute of the History and Theory of Architecture (gta) at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH). Together they’ve curated numerous international exhibitions on art and architecture including Readymades Belong to Everyone at the Swiss Institute in New York, Trix & Robert Haussmann at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin and the Nottingham Contemporary, and Inside Outside/Petra Blaisse — A Retrospective at Triennale Milano (all 2018).

A version of this interview appeared in PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020. Additional editing and writing by Akiva Blander.