GET OUT: A Swan Song to Trump’s Aesthetic of Trickle Down Mediocrity

“The world is an evil place, Charlie. Some of us make money off of that. Others get destroyed.” This from the lipless maw of an elderly jeweler in a dingy office on 47th street towards the end of Sidney Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007). Although pivotal scenes of this movie are set in the Trump World Tower on First Avenue, those that don’t occur in the drug dealer’s apartment in this nameless tower are usually phone-driven: messages get left, payphones get wiped, cell phones get snapped in half back when snapping a cellphone in half was both possible and somewhat inconsequential. The good old days.

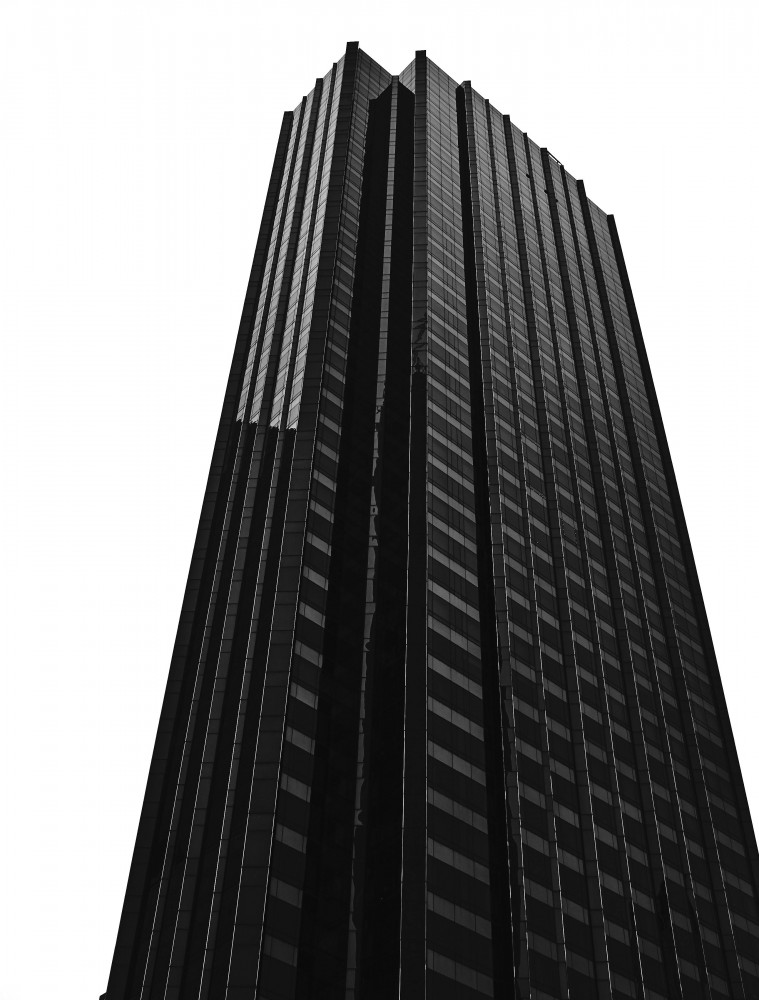

Trump International Hotel and Tower, formerly the Gulf & Western Building was designed by Thomas E. Stanley 1969–70. Photography by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

Punctuating that movie of grimy interiors and abject foldout beds in nameless tenements is the smoky-glass monolithic slab of the Trump World Tower (Costas Kondylis,1999–2001), where Philip Seymour Hoffman’s character escapes. I remember thinking, “Oh, of course that’s the sort of thing that would happen in that tacky, evil building.” Kondylis’s insta-tower rankled Turtle Bay residents when it went up because it blocked views of the United Nations headquarters across the street. No joke that the building’s most desirable apartments were sold to Russian buyers — it sneers darkly at the U.N. below it.

Formally, Trump World Tower meshes two buildings nearby: the U.N. Secretariat (Wallace K. Harrison, Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, et al., 1945–52), with its controlled cascade of casement windows sandwiched between stone slabs, and the Seagram building (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1954–58) a few blocks away on Park. Trump’s tower takes the murky tone of Mies’s bold manifesto and strips it of structural rigor: gone are the vertical mullions of polished-bronze I-beams — they would only collect the grime of the FDR Drive. Instead, the tower is half the width, twice the height, and anticipates post-9/11 anomie. Compared to the canonical mid-century Modernist predecessors nearby, Trump World Tower is like the cynical Cliff’s Notes: not about a corporate brand (Seagram’s), nor the honesty of bureaucracy (Lewis Mumford’s take on the U.N.), but asserting your own privacy at others’ expense. Bullet points:

- Fuck You

- Sue Me

Double page spread from PIN–UP 29, Revolution issue. Graphic design by OBG. Photography by Adrian Gaut.

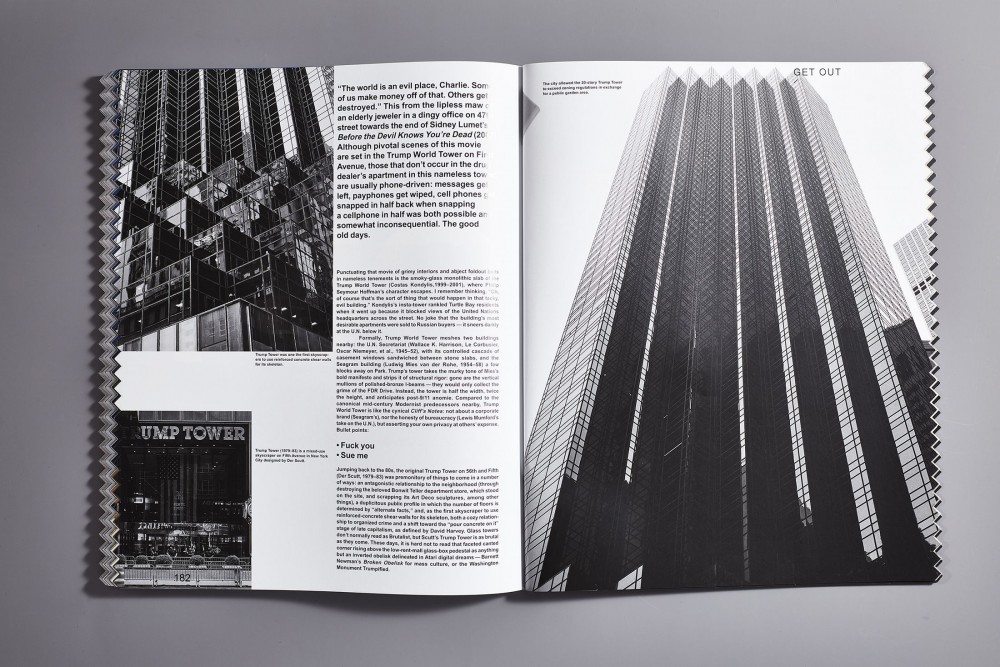

Jumping back to the 80s, the original Trump Tower on 56th and Fifth (Der Scutt, 1979–83) was premonitory of things to come in a number of ways: an antagonistic relationship to the neighborhood (through destroying the beloved Bonwit Teller department store, which stood on the site, and scrapping its Art Deco sculptures, among other things), a duplicitous public profile in which the number of floors is determined by “alternative facts,” and, as the first skyscraper to use reinforced-concrete shear walls for its skeleton, both a cozy relationship to organized crime and a shift toward the “pour concrete on it” stage of late capitalism, as defined by David Harvey. Glass towers don’t normally read as Brutalist, but Scutt’s Trump Tower is as brutal as they come. These days, it is hard not to read that faceted canted corner rising above the low-rent-mall glass-box pedestal as anything but an inverted obelisk delineated in Atari digital dreams — Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk for mass culture, or the Washington Monument Trumpified.

Trump Tower (1979–83) is a mixed-use skyscraper on Fifth Avenue in New York City designed by Der Scutt. Photography by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

If the Trump World Tower is an evil echo of the emptiness of International Style Modernist memories, the Dominick (Handel Architects/Rockwell Group, 2006–08, formerly the Trump SoHo) is vertiginous litigation embodied. It is tall, people died in its construction, and it attracts lawsuits like flies to shit. At Spring and Varick, one can only guess that it changed its name not because it isn’t really in SoHo at all, but because it Domin-ates Var-ick (sure there’s Dominick Street in its shadow, but…). This change of name, if not of heart, happened after the 2016 election. It’s a bad look to get caught looking bad. Surrounded by steel-framed, classicizing brick-and-mortar printing houses, the vestiges of SoHo’s cast-iron factories, and the Federalist remainder row-houses of the Lower West Side, the Dominick is mini-dick energy writ large in the sky. Shuffling on a raised plinth that echoes the earlier height of imaginary row houses and now constitutes the hotel-condo lobby-boutique, the slightly faceted tower is clad in glass that doesn’t so much reflect the sun and sky as absorb it: if you aren’t paying attention, you might miss it.

The Trump Organization converted the office tower into a hotel and condominium, with renovations by Philip Johnson and Costas Kondylis 1995–97. Photography by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

But it is there, and here’s the thing: none of these buildings are that bad. They’re not wonderful — Trump’s favorite architectural adjective — but they’re not necessarily abhorrent. The relationship between bad buildings and bad politics has never been pellucid. Trump’s simply seem like rote exercises in a safe bland Modernist pastiche, shimmering expressionism that doesn’t say much, easy enough to ignore. In all three, the sleek skin of planar glass deflects our curiosity about what happens inside. Before 2016, you could just ignore bad taste, and wish it away. The good old days.

Double page spread from PIN–UP 29, Revolution issue. Graphic design by OBG. Photography by Adrian Gaut.

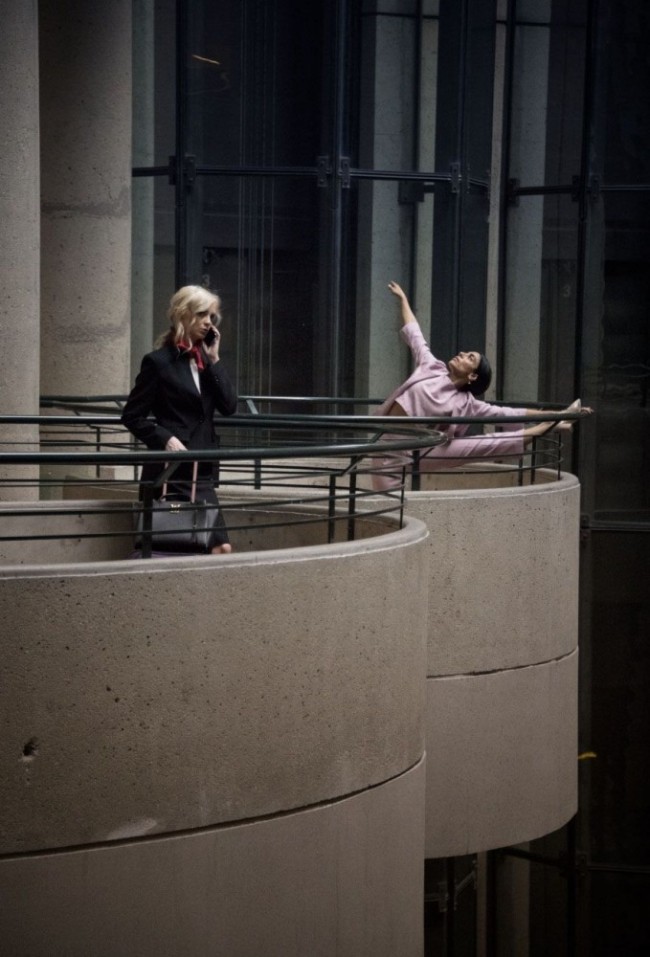

Back then, when bad men did bad things and we expected bad things to happen to them (not us) — 1995–97 to be precise — Kondylis and New York’s then-reigning (and fascist-loving) architecture tsar, Philip Johnson, collaborated on the gut rebrand of the 1968 former Gulf and Western building into the Trump International Hotel, located at (sort of) 1 Central Park West (Trump changed the address). Office buildings converted to transient residences — a combination of hotel room/condo units that vitiates any sense of community on the street — are nothing new in New York. 1 Central Park West is like an SRO for offshore capital and vice. Also eerily familiar is the shimmering homage to the 1964 World’s Fair at its base, reviled by most. No matter: Trump liked the globe, so Trump got the globe. Remember those rattan balls that used to decorate every tacky staged interior? The globe is like that, but chromed, threatening to tumble into the basket of Columbus Circle. But unlike his other buildings, which menace their neighborhoods, the Trump International Hotel seems right at home on Columbus Circle. That, perhaps, is only due to its tawdry and insensitive surroundings: the colonizer atop the column in the middle of the toilet bowl, for one, and the tribute to fake news, the USS Maine Monument, on the southwest corner of Central Park. Seen with these gaudy Beaux-Arts sculptures, 1 Central Park West seems right in spirit, if not in style. Historically, that rare corner site had been occupied by the Majestic Theater, a spectacular but underwhelming entrée to Broadway above 59th, the west side of which became increasingly seedy. It’s only right that an office building would be built there in the 60s, and a hotel there later. In those three roles — theater, office, hotel/condo — you have a century of New York’s appeal to the rest of the world in one site. The exclusively exorbitant, brassy insouciance of the current tower says something undeniable — and impossible to ignore — about what it means to live in New York today.

For marketing, Donald Trump changed the address of Trump International Hotel and Tower from 7 Columbus Circle to 1 Central Park West. Photography by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

And what does it mean to live in New York today, among and below Trump’s towers, buffered by outerboro golf courses? It means living with the ever-present reminder that we are indicted. To say that we let this happen is not quite right — we would be foolish to think we had that much power. It has always been there, and we ignored it. Rather, to live in the world today is to take part in its destruction, something we all do. Scapegoating the man doesn’t reverse the legacy, and Trump’s towers will be synonymous with this time long after the residue imprint of his glitzy name fades from the marquees of his buildings, below which oligarchs and oli-gawkers will stream, gazing at the shimmer of globes that never spun. What has New York City taught us about revolution? It only occurs in real estate.

Photography by Adrian Gaut for PIN–UP.

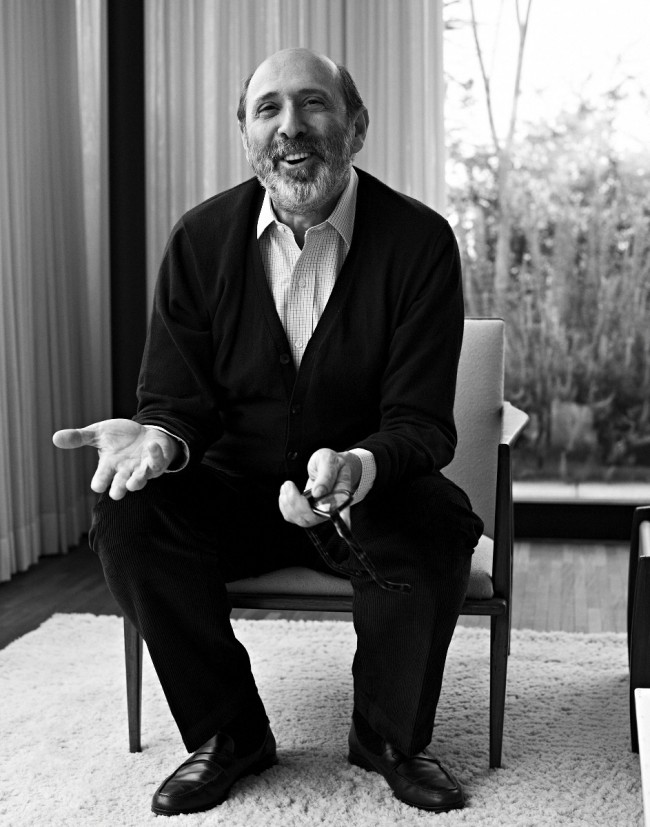

Ted Barrow is an art historian and writer who lives somewhere between New York City and Berkeley. While not finishing his dissertation on Gilded Age images of the tropics, he critiques skateboarding on Instagram.

An earlier version of this essay was published in PIN–UP 29, Fall Winter 2020/21.