HIBERNIA BANK: How A Beaux-Arts Building Became Witness To San Francisco’s Highs And Lows

San Francisco still shocks, but not in the way it once did. In this pandemic moment, while the racialized divide between rich and poor gapes ever wider, the vertiginous leap from urban squalor to spectacular wealth is more jarring than ever. Consider the Mid-Market area where, in the shadow of the Beaux-Arts rotunda of Arthur Page Brown Jr.’s City Hall and the surrounding Civic Center district, San Francisco’s contradictions are set out in sculptural relief. The bombastic remnants of top-down planning in a hastily-rebuilt precinct after the 1906 earthquake and fire, the City Hall and Civic Center represent one of the only full executions of the City Beautiful

-

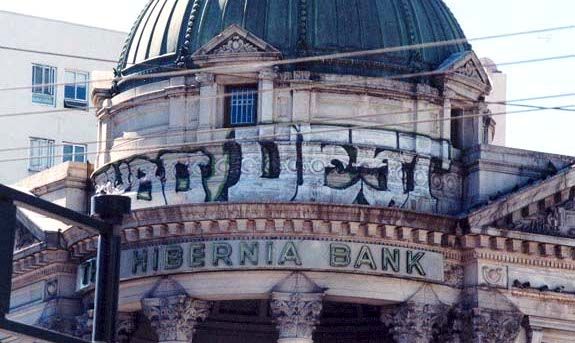

The Hibernia Bank building in San Francisco’s Tenderloin photographed in 2021 by Humberto Liechty.

-

Today the Hibernia Bank building at 1 Jones Street stands empty. Photography by Humberto Liechty.

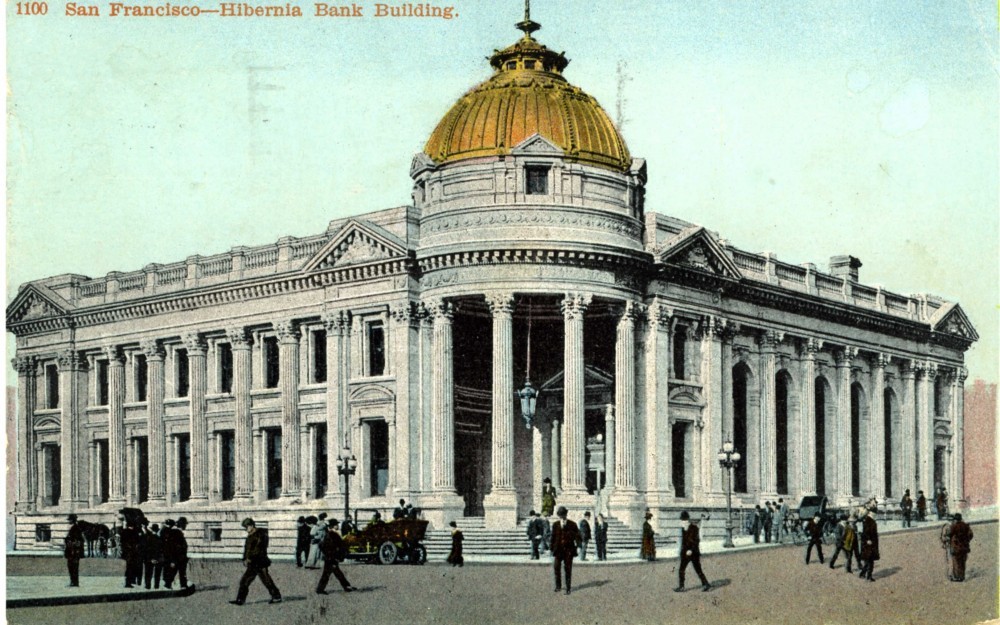

Pissis’s sepulchral bank building pins down the corner of Jones and McAllister, a radial intersection just off Market street, where the homeless and rival drug dealers jostle among the stands of a daily farmers’ market. Although San Francisco never adopted Daniel Burnham’s 1905 masterplan, the vestigial remains of the City Beautiful movement assert their place among the chaotic jumble of the laissez-faire city. Within that context, Pissis’s building, quickly nicknamed the Paragon by fellow architects and fans when first unveiled, inaugurated the full-blown Beaux-Arts style on the West Coast. Mexican-born Pissis (1852–1914) was the first San Francisco-raised architect to be trained at Paris’s École des Beaux Arts, and with the Hibernia he brought back to the Barbary a robust and elegant expression of Second Empire eclecticism, its Italian-Renaissance quotations combined in a composition of typically Haussmannian massing. Though not free-standing, the domed entrance rotunda that turns the corner in classic Parisian style can trace its roots back to the mother of them all, Bramante’s Tempietto at San Pietro in Montorio, Rome.

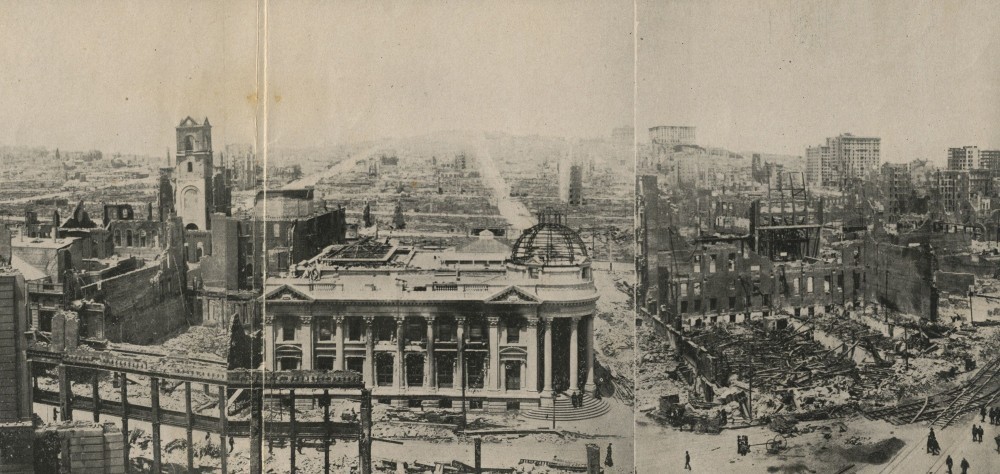

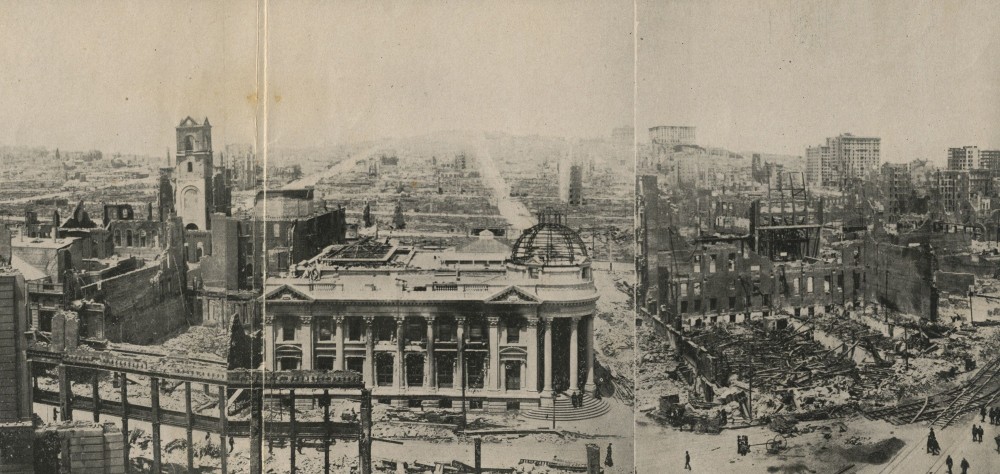

The Hibernia Bank opposite ruins of the Prager department store after the earthquake on April 18, 1906. Photographer unknown.

A devotional chapel built over the purported site of the crucifixion of St. Peter, the Tempietto was begun in 1502 at the behest of the Spanish sovereigns Ferdinand and Isabella as testament to their piety and special relationship to the church: in 1494, Pope Alexander VI had conferred on them the title of Catholic Monarchs in recognition of their defense of the Catholic faith within their realms. Among their actions was the completion of the Reconquista, when they defeated and expelled Muhammad XII, the last Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada, in 1492 — the same year they financed Columbus’s first transatlantic exploration. With the Tempietto, the Catholic Monarchs ushered in a tacit bond between a militarized church soon to expand into the Americas and the deployment of Classical architectural form to express imperialist power. Like a little pebble thrown into the sea, Bramante’s circular chapel would radiate out in influence across the globe, just as Spanish imperialism spread outwards over the Americas, with its colonies, extraction of wealth through despoliation, and indigenous genocide, a history of which San Francisco itself was initially a part.

A postcard featuring the Hibernia Bank Building designed by Albert Pissis in 1892.

In the first half of the 19th century in the USA, Greek Revival Classicism was seen to embody the young nation’s democratic ideals, drawing a stylistic link between ancient-Greek and modern-American democracies. Between the 1860s and the 1880

The Hibernia Bank building was one of the few in the Tenderloin to survive the earthquake and fire of 1906. Photography by Wilbur Gleason Zeigler.

Like the Bank of Italy

The aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake captured by Wilbur Gleason Zeigler and published in his book The Story of the Great Disaster.

Like its 19th-century namesake on the westside of Manhattan, San Francisco’s Tenderloin was an openly-sanctioned vice district from the 1850s onwards. Its Beaux-Arts apartment buildings, French restaurants, popular theate

-

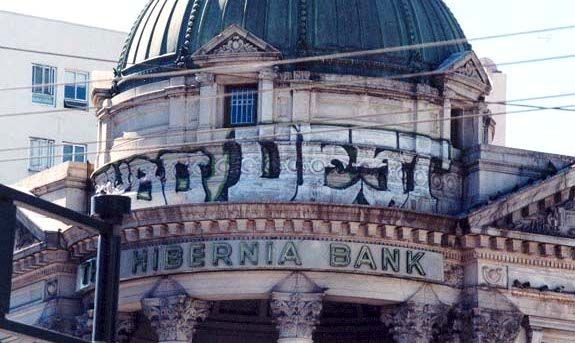

Graffiti bomb on the vacant Hibernia Bank building circa 2010. Images courtesy sfist.com

-

Graffiti bomb on the vacant Hibernia Bank building circa 2010. Images courtesy sfist.com

The Hibernia building speaks to this change in imperatives: once an elegant fortress

But you wouldn’t know all that about the Tenderloin from the sidewalk, standing before the Hibernia at a crosswalk at McAllister, Jones, and Market. On one side, a drug crew holds down the corner, on the other the unmasked and unprotected homeless continue their peculiar urban flânerie, and the Paragon appears paralyzed in a paroxysm of uselessness: a picturesque architectural folly for Gilded Age ideas of the City Beautiful imagined, and the city manifest today.

Ted Barrow is an art historian and writer who lives somewhere between New York City snd Berkeley. While not finishing his dissertation on Gilded Images of the tropics, he critiques skateboarding online.