INTERVIEW: Fraternal Architecture Duo Leong Leong EMBARK ON A NEW CHAPTER

Chris and Dominic Leong were born 17 months apart, but so symbiotic is their behavior that one could be forgiven for thinking them fraternal twins. Born and raised in St. Helena, in scenic Napa Valley, the brothers cut their construction-site teeth helping their architect father Wayne build the family home. After studies at Berkeley and Princeton (Chris) and Cal Poly and Columbia (Dominic), they ended up in New York, where they worked for the likes of Bernard Tschumi, Gluckman Mayner, and ShoP Architects, until, in early 2009, they pooled their talents to found Leong Leong. With clever, experimental, self-initiated projects — a rose-hued grotto made from layered insulation (the 2010 installation Turning Pink) or a container filled with spray-foam-covered ramps (Soft Brutalism, a 2010 temporary store for designer Siki Im) — as well as more classic retail projects and apartment renovations, they quickly made a splash on the architectural scene. At a time when the thinkers are increasingly separated from the doers, Leong Leong’s combination of hands-on pragmatism and theoretical experimentation sets them apart from the crowd. The brothers have developed a signature approach, combining manual materiality and an attempt to defuse the complexities of modern life. With a decade’s experience under their belt, awards from both the Architectural League of New York and the AIA, and three large-scale projects — a hotel in San Francisco, a community center in Queens, both in development, and the recently completed Anita May Rosenstein Center in Los Angeles (read Mimi Zeiger's brilliant review here) which opened its doors May 2019 — Leong Leong have reached a watershed in their career. PIN–UP caught up with them in their office on New York’s Bowery to talk about foam, diversity, and their love of simple shapes.

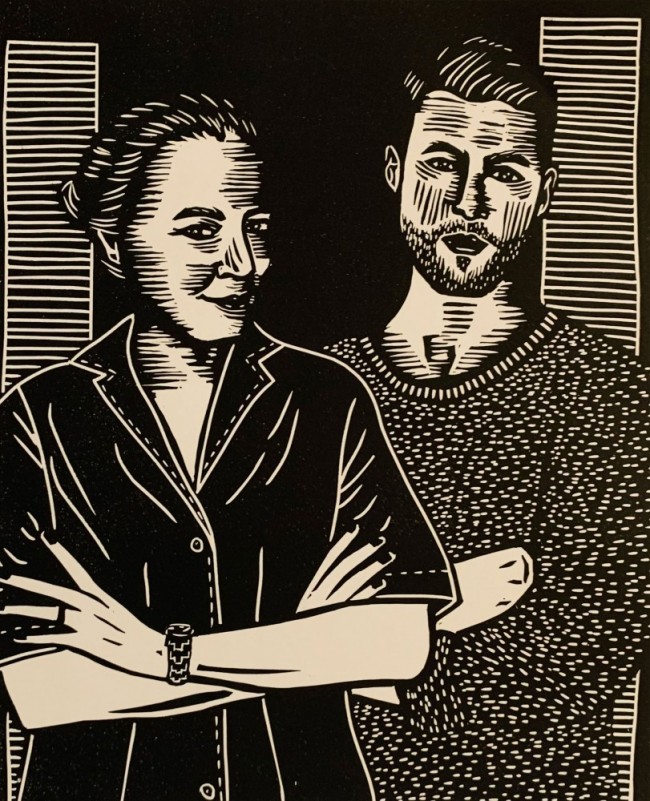

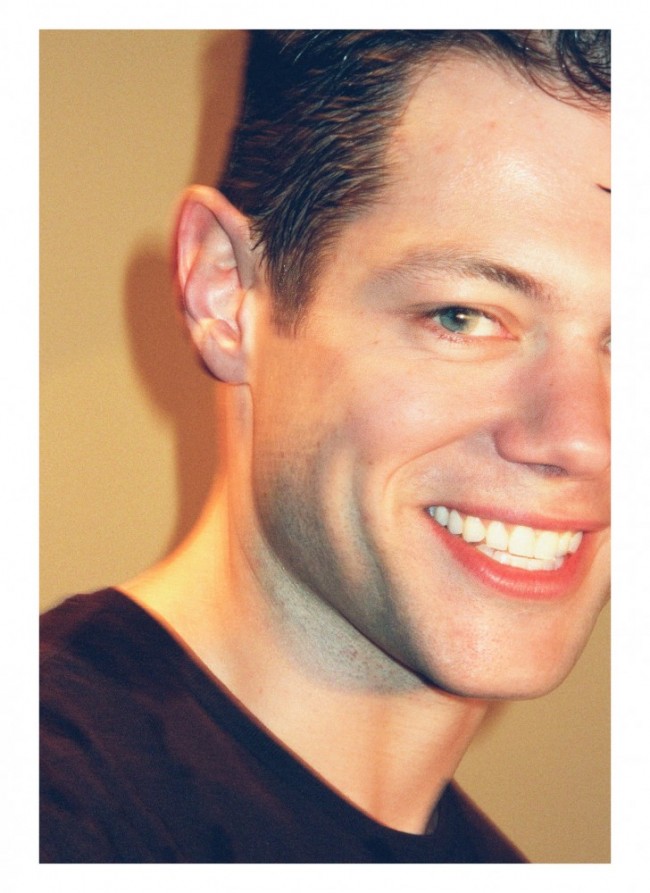

Portrait of Dominic and Chris Leong by Bruno Staub for PIN–UP.

You’re both architects, and your dad is an architect. Architecture really runs in the family!

Dominic Leong: Well, our dad is an architect, but he has an unconventional trajectory. He first studied engineering and then went to do research at MIT in artificial intelligence and cybernetics. But MIT was part of the military-industrial complex and this was in 1968, and the Vietnam War was going on. So our dad decided to quit out of protest because he didn’t want to be part of that. So he moved back to Napa Valley with other hippie sorts of characters. First he became a cabinetmaker, then a carpenter and contractor, then a contractor-architect, and finally an architect. So where architecture is concerned he’s completely self-taught.

And he built the house you grew up in, right?

DL: Yes. He and our mom still live there. It looks a bit like an early Robert Stern meets Shinohara Kazuo.

Chris Leong: Well, it was kind of between those two. This was at a time when Robert Stern, Robert Venturi, and Charles Moore were doing a lot of modern vernacular houses. Our father also really liked Bernard Rudofsky’s Architecture Without Architects and some of those other hippie architecture books. And there were also a lot of AD and GA books around with work by Japanese architects. The house has two elements: a barn that was inspired by one of Shinohara Kazuo’s projects — the Tanikawa House, which had a large gable and a sloped earth floor — and contemporary East Coast architecture that really played with historical form and with materiality like clapboard. There was literally a bridge that connected the two… Basically it’s Nor-Cal PoMo.

Like an earthy PoMo?

CL: It’s not so earthy. Maybe DIY PoMo is a better term for it. It’s a complete amalgam with no real governing ideology. There are all of the amenities that you would need for a self-sustaining environment. It’s his ongoing project, and he’s just adding on to it every five seconds. (Laughs.)

DL: I don’t think the house will ever be finished. (Laughs.)

With your father being an architect, was there ever a moment where you said, “That’s the last thing I want to do?”

DL: We grew up working on the house during the summer, painting and doing all kinds of manual labor, so I never really thought, “Oh, I really need to go and study architecture,” I just did it because I grew up around it. So I always knew I was going to college for something design or architecture related. And the reason I wanted to go to Cal Poly, in San Luis Obispo, was because it’s on the coast and I could surf. (Laughs.) But then I just became totally obsessed with architecture and eventually decided I needed to go to graduate school. I ended up here in New York, at Columbia.

-

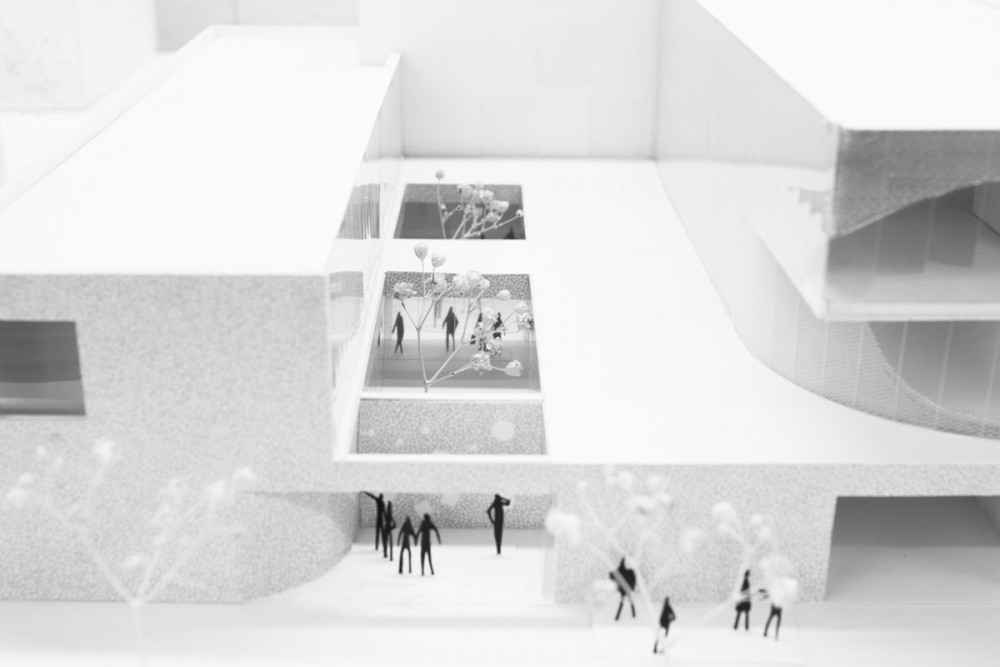

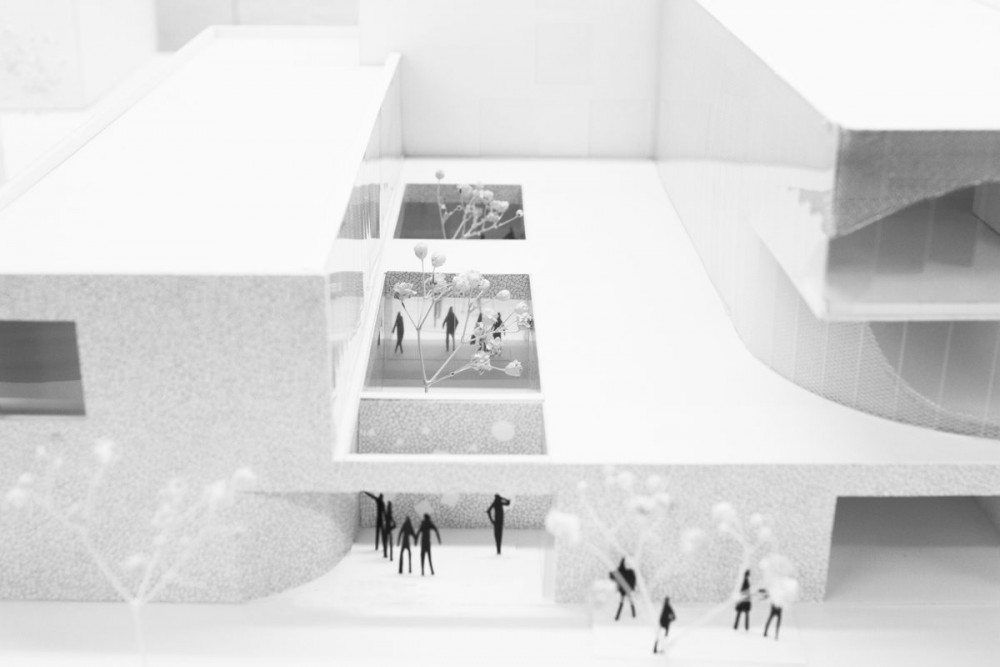

The Anita May Rosenstein Campus is a multi-generational, community-based LGBT center in Los Angeles. Leong Leong’s 183,700-square-foot design, which recently broke ground, includes affordable housing for seniors and young adults, a center for homeless youth, and a cultural event space.

-

The Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus. Photo by Iwan Baan.

-

The Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus features a series of courtyards. Photo by Iwan Baan.

-

The Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus, view from Santa Monica Boulevard looking north. Photo by Iwan Baan.

-

The Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus's Pride Hall event space along North McCadden Place. Photo by Iwan Baan.

Did it ever seem strange to either of you that you were doing almost the exact same thing?

DL: Chris was actually in New York first, working for Gluckman Mayner. And then I went to Columbia and he went back to California for a bit before going to grad school at Princeton. It was kind of back and forth.

CL: I think our whole childhood was a bit like that, always kind of looking at what the other one was doing, doing the same things, but in different cities, at slightly different speeds. Dominic had his inner network in Cal Poly and I had mine at Berkeley. Then we went across the country, crossed paths, then I went to IUAV in Venice, then he went to Paris to study. We were never doing exactly the same thing, but we were always in each other’s minds.

Why did you decide to work together?

DL: I had been working as the partner-in-charge at PARA Project on the Phillip Lim flagship store in West Hollywood, which completed in 2008. I’d developed a good relationship with the client and eventually they wanted to work on more projects, which led to a townhouse commission in New York and another Phillip Lim store in Seoul.

CL: At the same time I was working at SHoP. It was the pinnacle of the recession and I remember we were desperately looking for projects. I realized that I could either be stressed out working for someone else or stressed out working for myself. So Dominic and I decided to take the leap together.

What are the best and worst things about working with your brother?

CL: The best thing is trust.

DL: Yes, I agree. The worst thing?... A lot of times much of the tension in the office comes from the need to have one singular voice. Obviously we have two voices, and I think once we realized there are actually three voices — Chris’s voice, my voice, and the voice of the office — that really helped. Sometimes the office voice is in agreement with both of us, sometimes it isn’t. Once we made that shift in the way we think about our identities, it became less of a problem. But that’s probably a brother dynamic we’ve been navigating our whole lives.

Dominic and Chris Leong photographed by Bruno Staub for PIN–UP.

It seems to be working — you’ve grown so much over the past decade.

DL: Well looking back on it, I realize how fortunate we were to have had those two projects right out of the gate, the Phillip Lim store in Seoul and the Manhattan townhouse. I think we took it for granted then. And sure enough, once we completed those, we were just doing installations that got progressively smaller and smaller. (Laughs.) It’s around that time that Turning Pink happened, the installation we did at W/ Project Space in Chinatown. It was part of a series of self-initiated installation projects that we started in order to avoid getting pigeonholed as retail architects. Turning Pink also marks the moment when our material experimentation began. And somehow that has become a defining aspect of our practice.

With respect to your material experimentation, most people will think of foam.

CL: We do like to work with foam. (Laughs.)

DL: Are you asking “Why foam?”

Well, yes. I’m interested in your material experimentation in general.

DL: I am always resistant to defining our practice through materiality. But I think the most honest way to answer is to say that we do have a real fascination with materials, and it probably has to do with the fact that we grew up making things with our hands. We always pick a material that we are obsessed with and then we simultaneously develop the concept. It’s really about understanding the relationship between the two. Our obsession with foam is partly because it’s malleable and you can achieve a lot of formal expression in an efficient way.

CL: And it’s also tactile. It has texture. It’s soft. You can sit on it. It’s something you touch, whereas with concrete there’s a bit more distance between you and the material. And it’s also playful.

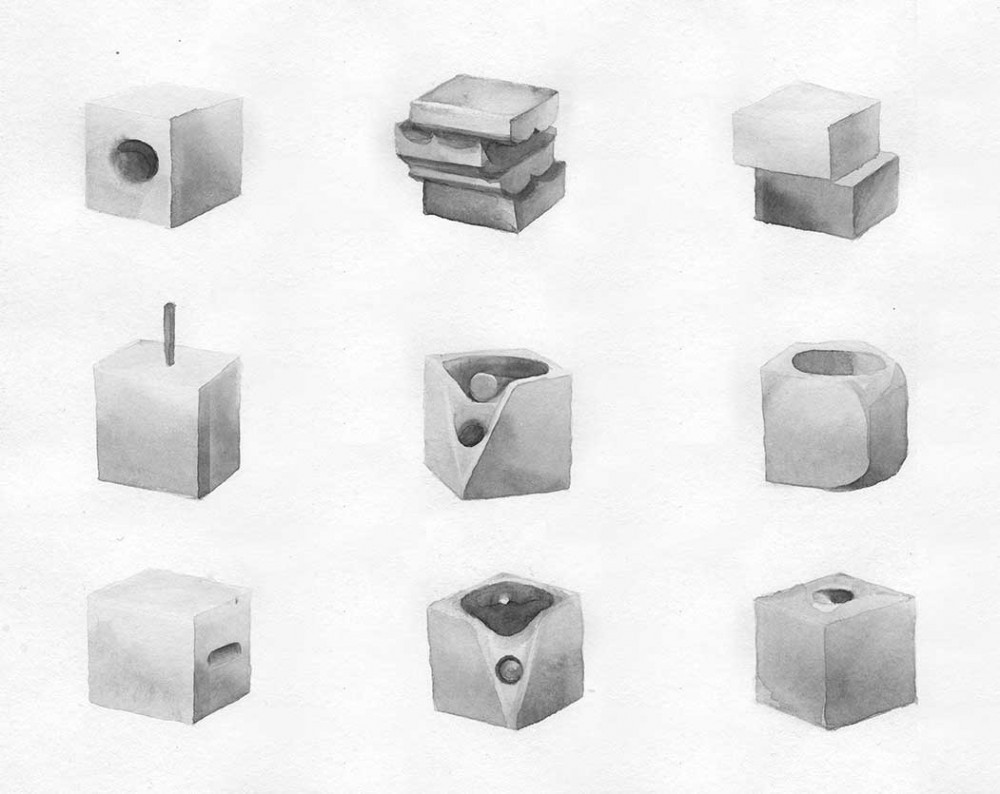

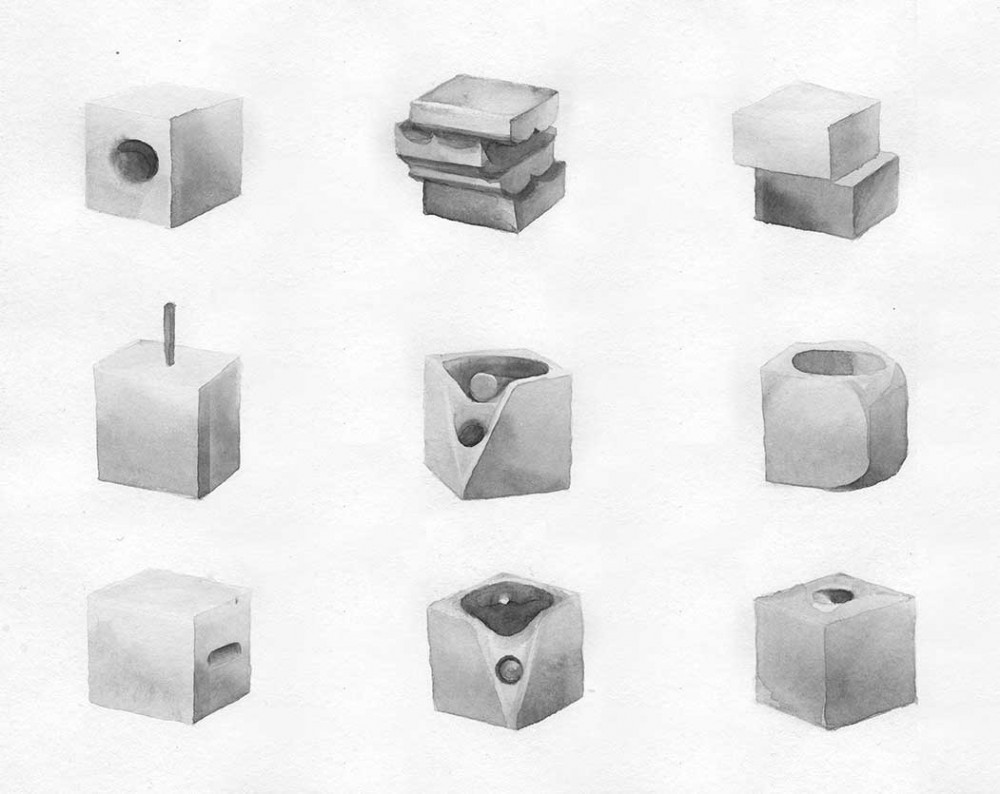

A Toolkit for a Newer Age (2016) is a collection of nine objects milled from Himalayan salt meant to satisfy basic human needs. The 8x8-inch objects were created especially for Chamber Gallery in New York and are part of Leong Leong’s ongoing exploration of simple geometric shape typologies.

It’s interesting you mention soft as such a positive characteristic in architecture. There’s a project of yours called Soft Brutalism. But the term could be applied to many of your projects. Not only Brutalist in the aesthetic sense, but also from a conceptual point of view — the idea of soft materiality and rawness.

DL: You can have this very rigorous geometry and undermine it with very playful materials. I think that’s an interesting tension.

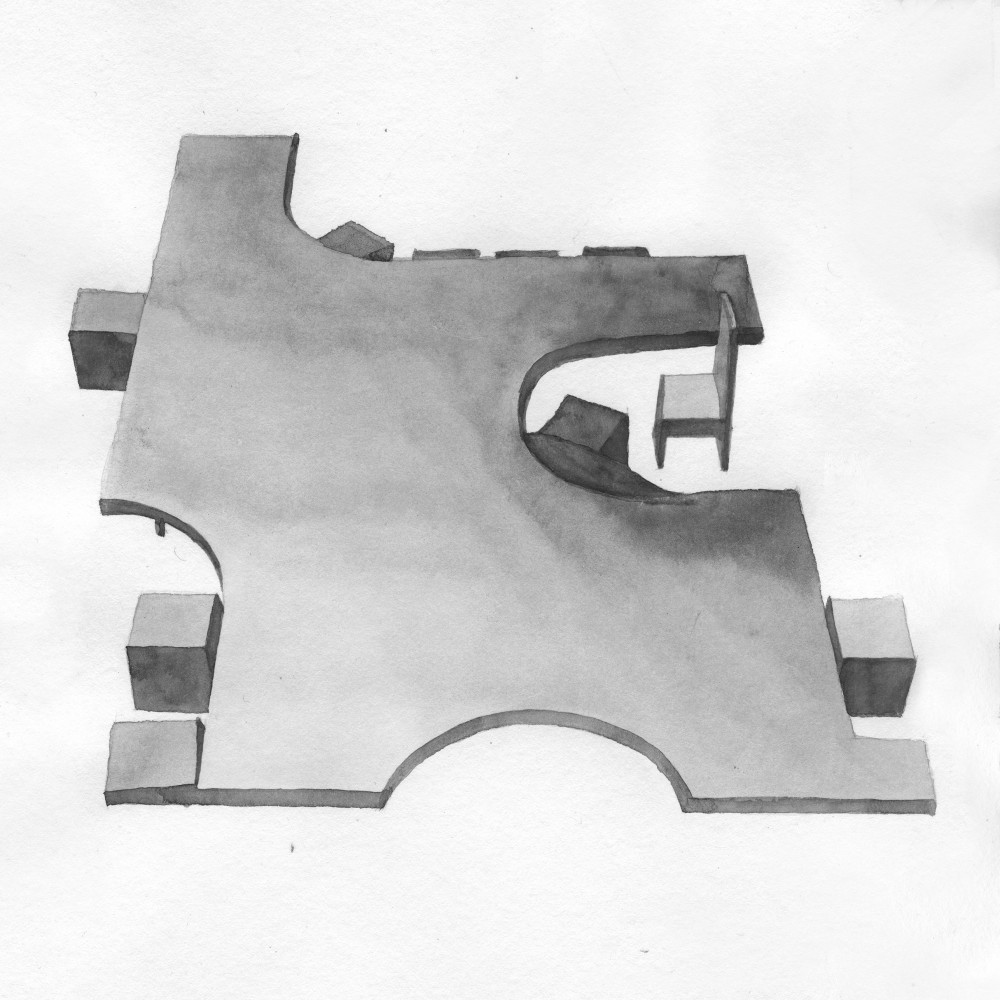

CL: I think what also relates to the idea of softness is our process as architects who design from the inside out. We tend to think even of our larger projects as interior projects. With large-scale projects like the LGBT campus in L.A. , we conceptualize them based on the idea of interior courtyards. It’s an inside-out approach, rather than from the outside in.

DL: It’s a weird conflation of an interior way of thinking about space, and then zooming out to the city — taking something that would be at a monumental scale and breaking it down into the most domestic scale. When we did the LGBT campus, we thought of it as an interior project. It was very much more about resolving the program at a domestic scale and aggregating that outward toward the city. The courtyards are all interior so you could call it an aggregation of interiors that collectively make up an urban form. Which is very different from an approach that immediately asks, “What is the urban form?” To me, that is what is really compelling about that project, that there is no grand gesture on that corner. It’s not a monument, it doesn’t have that one iconic moment. We are interested in a post-iconic architecture.

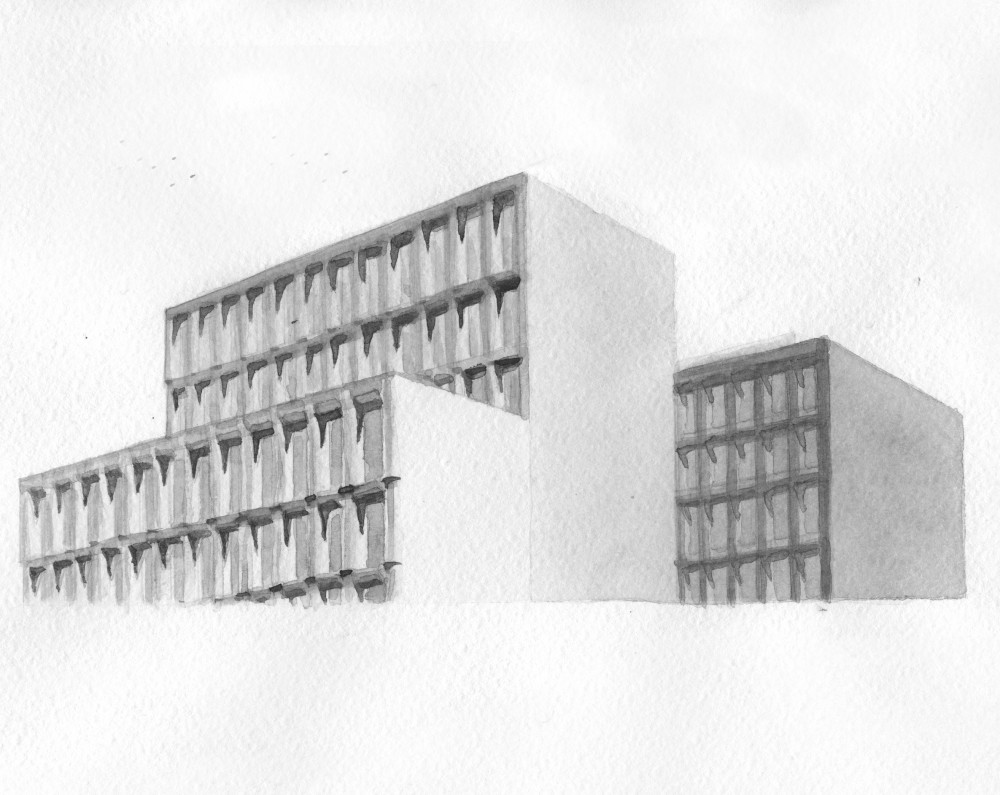

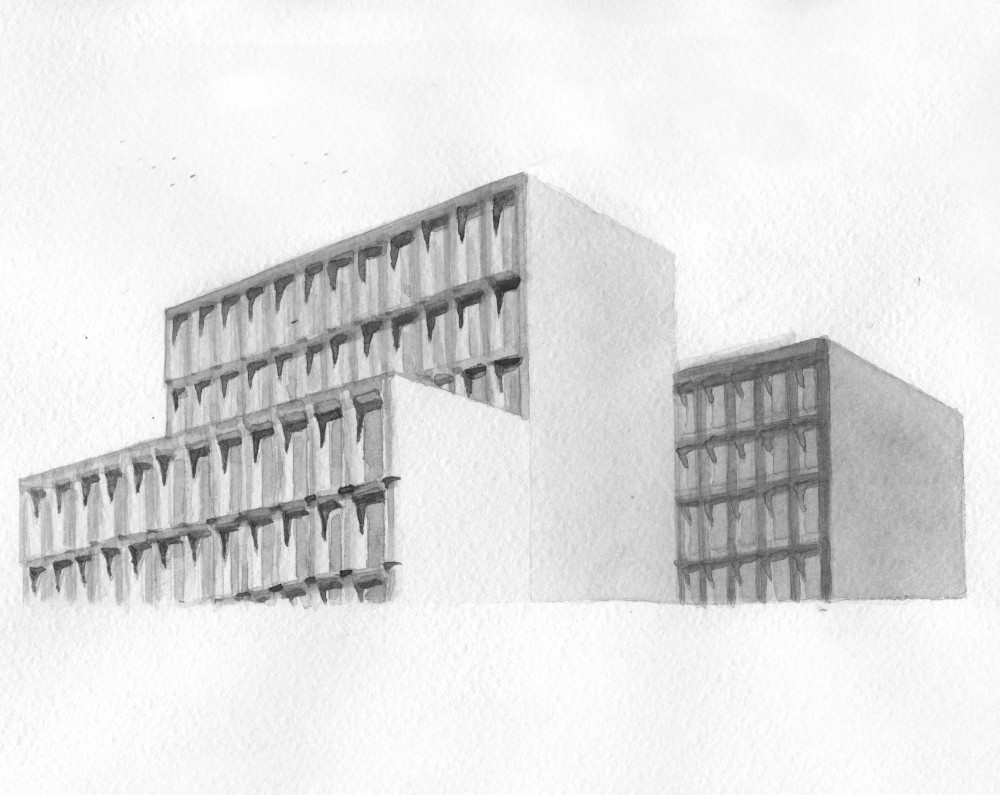

The seven-story Center for Community and Entrepreneurship (2018) for the Asian Americans for Equality organization in Flushing, Queens is a mixed-use community building divided into four volumes. Built in collaboration with JCJ Architecture, it is Leong Leong’s first large curtain wall project.

Is this something that is specific to Leong Leong? Or do you see this as part of a more general trend in architecture?

DL: I think a big question about our current culture is how do we relate to the speed of experiences as they accumulate around us? How do we come to terms with hyper-complexity? And where does architecture sit within this world that is increasingly complex?

I’ve heard you use the term “primitive modern” to describe the use of simple geometries in your work. What do you mean by that?

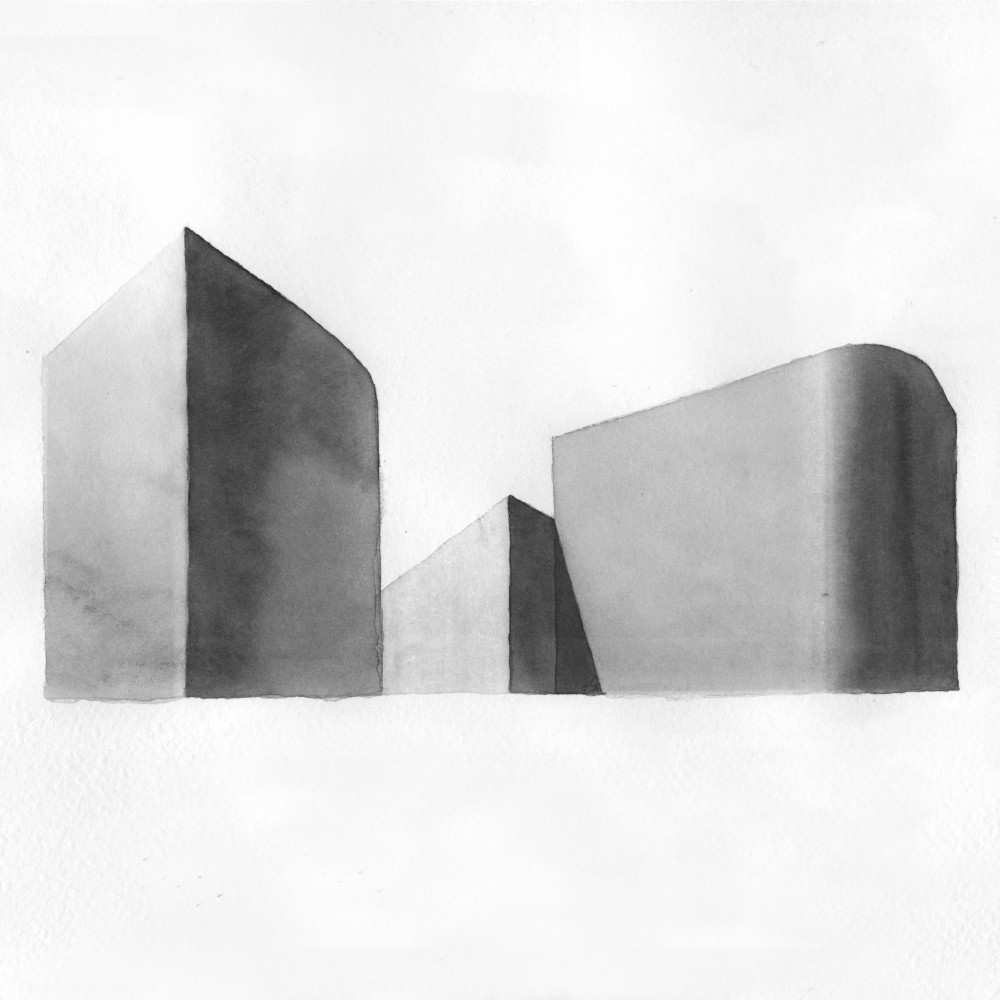

DL: We like so-called “primitive” shapes because they have a certain legibility to them. Maybe in a way that has to do with getting out of complexity. So a simple shape is somehow more desirable as opposed to a super-complicated shape. We’re in search of unexpected coherence as an antidote to complexity, even if it’s a temporary illusion.

CL: To me the primitive is also the attempt at finding an essential form, an elegant form, by using the least amount of effort to achieve something that is distinct. There is something about that in the notion of the primitive and the act of attempting to distill things down.

DL: One defining element of a Leong Leong project is a super-clean organizational plan, often containing primitive shapes. Only when we introduce the aspect of materiality do we somehow deliberately obscure or undermine that formal clarity. It’s a process that constantly plays out in almost all of our projects. It’s the idea of breaking something down into very clear terms of program, plan, and organization, and then again adding layers of complexity. Another way to define the primitive modern is the search for something that transcends the relentless acceleration of technology while being immersed within it. I always think about it as, “Can architecture be fast and slow at the same time? Can we embrace the acceleration of the world and also slow it down?” I have all of these theories about which architects are fast architects and which are slow architects.

Is Leong Leong slow or fast?

DL: I want us to be both. (Laughs.)

Leong Leong’s official start date was February 2009, which means you began two weeks after the Obama inauguration. For 99 percent of the time your practice existed in…

DL: …an era of optimism.

With the Trump administration, what is the new paradigm for architects to operate in when the status quo isn’t really about social progress anymore? I’m thinking in particular about your work for non-profits, both of which deal with minorities. Can you explain a little bit what they are?

CL: The one in Flushing is called the Center for Community and Entrepreneurship. It’s run by a non-profit organization called Asian Americans for Equality, a platform that supports minorities and marginalized communities — not just the Asian American community. They are a large affordable-housing developer in Lower Manhattan, they provide financial services, and they started out as an advocacy group. Since then, they have grown to providing many different things. The mission of the building is to provide a physical space that is a platform for small businesses and community organizations to have events and exchange. The LGBT Center — the Anita May Rosenstein Center, to be exact — is a mixed-use campus in Hollywood that combines housing, senior housing, at-risk-youth housing, and social services. There is a drop-in shelter for kids coming off the street, along with an educational component, administration, and a cultural-event space. Both of these projects are really interesting, because in both cases what were once completely marginalized communities have now evolved to the point where architecture can be made in their name for their mission. That’s when you realize why architecture is important, because through it you can provide visibility for a community that was never expressed architecturally before. You invent a new typology for a community, and all of a sudden it has a presence in the city, and it makes that community legible from a civic point of view.

-

The Anita May Rosenstein Campus is a multi-generational, community-based LGBT center in Los Angeles. Leong Leong’s 183,700-square-foot design, which recently broke ground, includes affordable housing for seniors and young adults, a center for homeless youth, and a cultural event space.

-

The Anita May Rosenstein Campus is a multi-generational, community-based LGBT center in Los Angeles. Leong Leong’s 183,700-square-foot design, which recently broke ground, includes affordable housing for seniors and young adults, a center for homeless youth, and a cultural event space.

-

The Anita May Rosenstein Campus is a multi-generational, community-based LGBT center in Los Angeles. Leong Leong’s 183,700-square-foot design, which recently broke ground, includes affordable housing for seniors and young adults, a center for homeless youth, and a cultural event space.

You could say the same thing about the National Museum of African American History and Culture, another example of an architectural manifestation of a culturally marginalized demographic.

DL: Yes. In a way, the best part of architecture is about self-actualizing culture and society. This is why aesthetics are social, because all of a sudden you can allow for new associations and perceptions to happen between people and their environment.

CL: What’s also interesting about these projects is that they create new typologies within their context. For example, the LGBT center has six different types of housing, as well as social services and a community space all on one campus. That’s not a typology that already exists. Meanwhile the Center for Community and Entrepreneurship in Flushing is a multi-floor commercial space that is very community-oriented. That is more of an Asian typology. So these two projects emerge out of very different cultural circumstances and are very much an evolution of their context, be it Flushing or Hollywood. So in a political climate that is increasingly anti-global, and that is trying to retreat back to a time when America was supposedly great, the real change is coming from minorities and immigrants.

I get the impression that the world of architecture always congratulates itself on how open, liberal, and inclusive it is. But then you see the reality in most schools and offices — and I include myself in this — and you realize it’s just another echo chamber.

CL: I ask myself that question a lot: “Are we, as an office, diverse enough?” It’s becoming more of a priority. It really began when we started working on the LGBT center. So this idea of asking who or what is the world in which we are operating, and are we reflective of that world — we’re becoming more and more conscious of that. As we grow, we continue to bring new and diverse voices into the office.

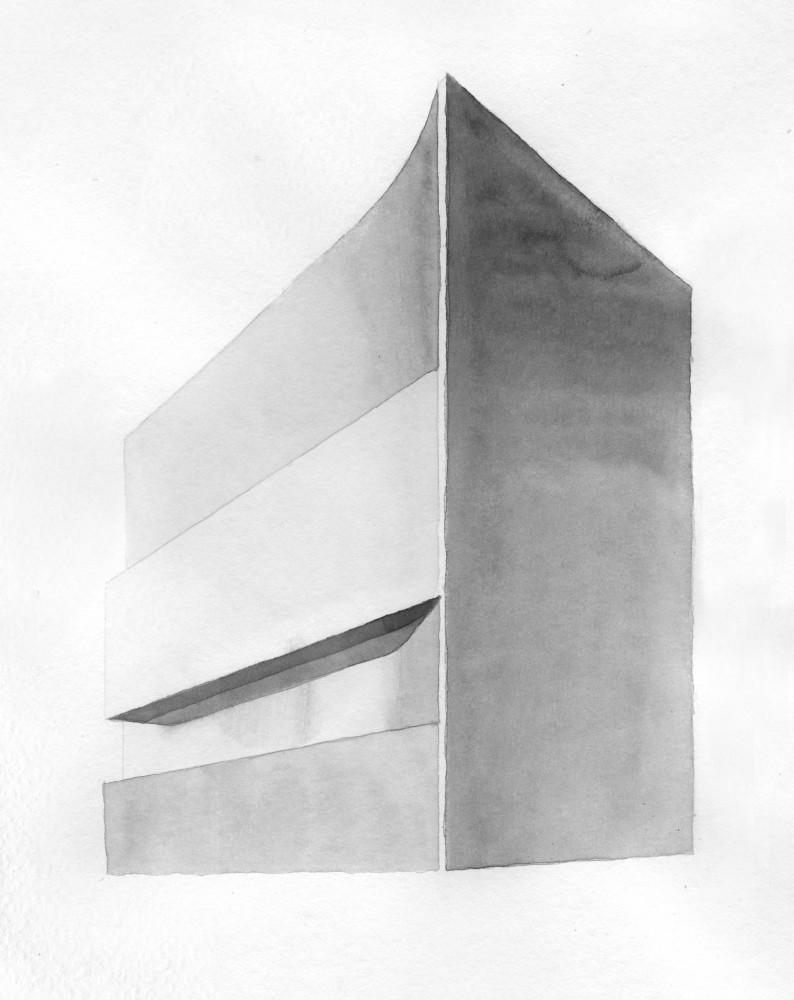

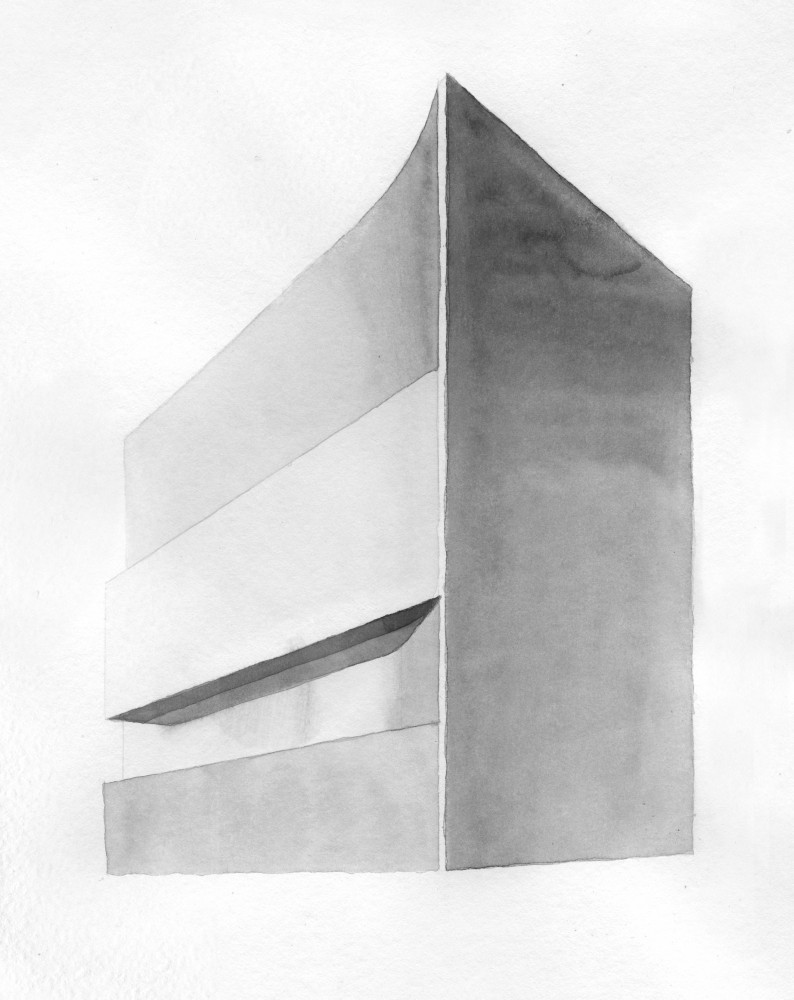

Leong Leong’s design for the planned Eaton Hotel offers access to co-working spaces, a media center, and a screening room amongst other amenities. Located in downtown San Francisco, the hotel shares public and private spaces across four volumes. It’s scheduled to open in 2019.

Speaking of office culture, in 2014 you participated together with Storefront for Art and Architecture in the Venice Architecture Biennale. The theme was OfficeUS, and your installation was a prototype for an architecture office in the U.S. pavilion.

DL: Yes. We were thinking about Rem Koolhaas’s fundamentals — what are the fundamentals of the architectural office? What is the role of the archive? We realized that it becomes increasingly important for contemporary practices, because we produce a lot more work that requires a lot more editing. The archive is a continually curated repository of ideas that recirculate and return. It becomes a garden that you are constantly tending. The table we designed for OfficeUS was essentially an interface and an archive. It was the living archive of the architects working in the pavilion for the duration of the biennale, producing things. The artifacts became embedded in the table, and the table itself became a moment for the public to interact with what the architects were producing. The table became a format for dialogue.

CL: A big takeaway from that project was rethinking the office space as a place of exchange. If you look at our office now, we share the space with two graphic designers, and there are multiple people coming and going to every desk. It’s a space where multiple entities function together. That was a switch for us since we moved into this space. Being in such a workspace allows us to collaborate with these graphic-design firms — Project Projects and MTWTF — and we organize a monthly salon where we have talks initiated by the different entities and then document the conversations.

-

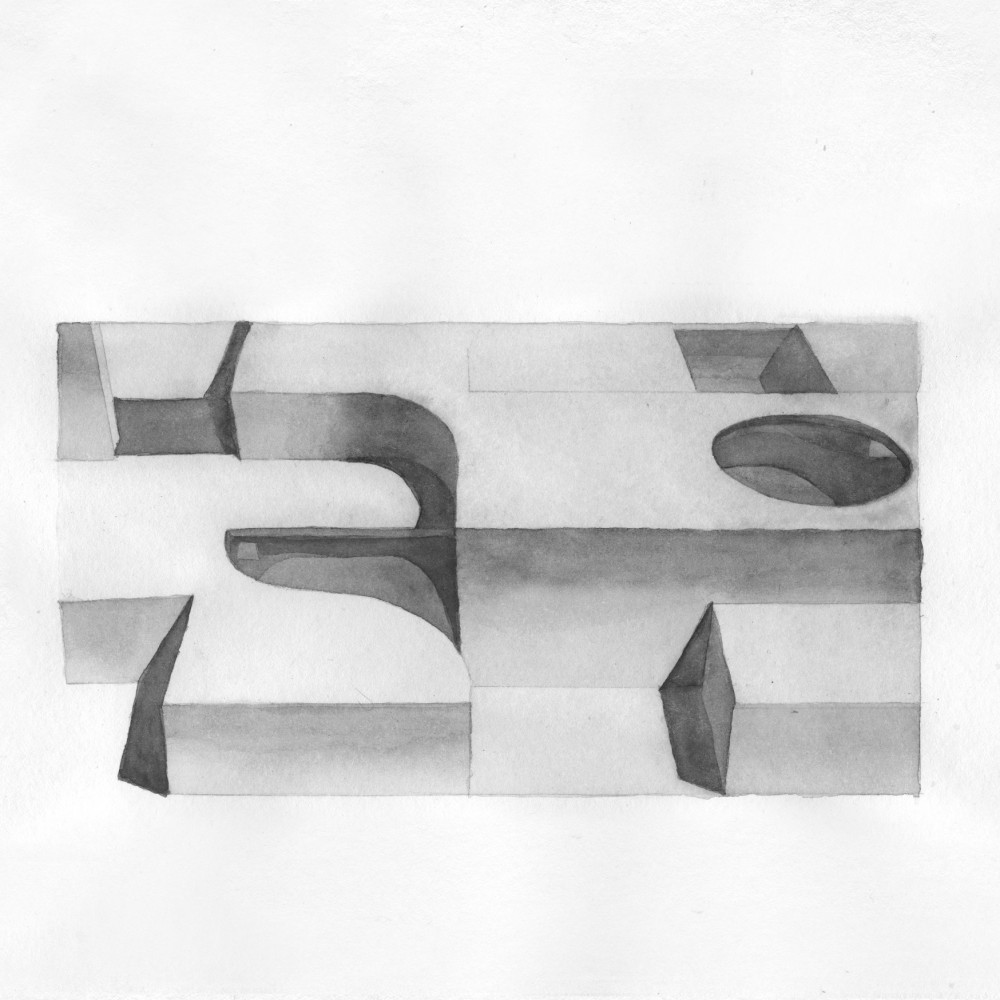

A worktable Leong Leong designed for their OfficeUS installation at the American pavilion during the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. Led by New York’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, the exhibition and project room looked back at U.S. architectural production over the last 100 years.

-

One of Leong Leong’s earliest projects, the West Hollywood flagship store for 3.1 Phillip Lim (2008) is built inside an existing building. The plan shows textured walls in a continuous curve that offer niches for garment display and changing rooms.

Does this play into your decision to stay in New York, despite your global workload? Why are you still here? (Laughs.)

CL: New York is an interface of exchange. It’s a place that connects all of these other parts of the world. The context of New York is what allows you to operate globally.

DL: Though you can also get too defined by your context. That is one of the shortcomings of New York, because you can get sucked into just trying to survive here.

CL: I always have a little bit of regret. I wonder why I didn’t just find a smaller city to operate in and pick a certain typology to really work through. I think that will be what is interesting about the Emerging Voices Award, because there are firms that operate in Jackson, Mississippi and Portland, Oregon, and places like that, and they have the luxury of working in this one place to develop this one building system and perfect it. For us there is less of an opportunity to refine a single building type, it changes constantly, every year. That is to me what it means to embrace the New York context. We’re going to jump scales, we’re going to jump contexts, but we’re going to be here.

You’re more malleable? Like foam?

DL: Yes, we’re just like foam. We’re plastic! (Laughs.)

Interview by Felix Burrichter

Portraits by Bruno Staub.

Architecture photography by Iwan Baan.

Watercolors by Elena Ivanova.

An earlier version was published in PIN–UP 22 Spring Summer 2017.