ORTHOREXIA: An appetite for Purity From Healthy Eating To Horizon-Line-View Real Estate

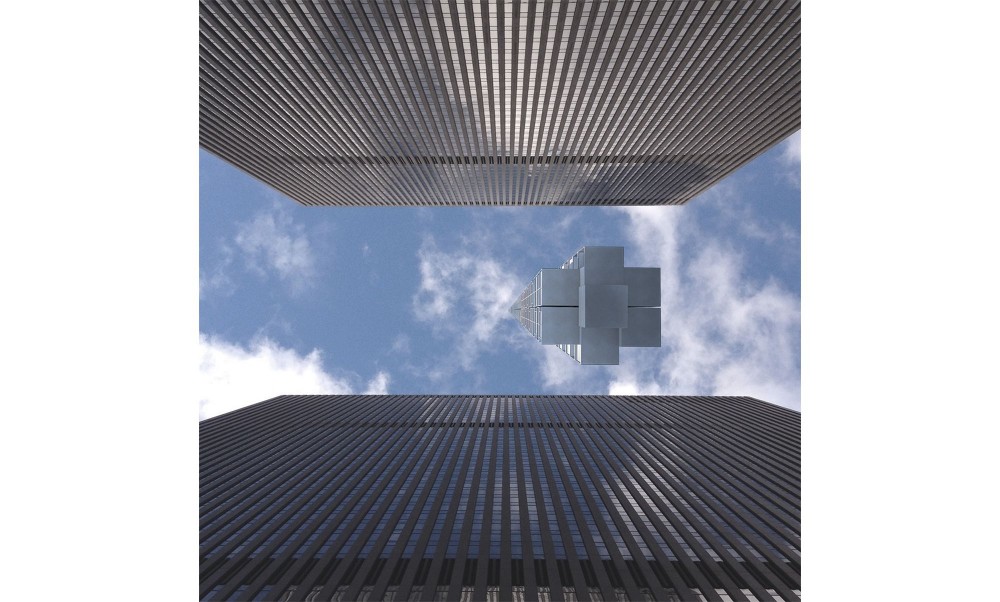

Analemma Tower, a conceptual proposal for the world's tallest bolding ever by the artist Ostap Rudakevych and Clouds Architecture Office. Prefabricated units are hoisted to the upper limits of the troposphere. (Ostap Rudakevych/Clouds AO)

We are all orthorexics. Everyone has his or her own ortho: a metal grill aligning the teeth, a wedge in an insole, a tradition to conform to, an x and y at a right angle. Through the orthodontic, orthopedic, orthodox, and orthogonal, our flesh, spirit and mind seek order and control. Literally, orthorexia means an appetite for something right or correct. It comes from the Greek orthos (“right” or “straight”) and orexia (“appetite” or “desire”). However, as a term first coined by alternative-medicine physician Steven Bratman, orthorexia has nothing to do with braces, spongy shoes, Jewish side curls, or plumb bobs. In 1997, Bratman used “orthorexia nervosa” to diagnose patients who were obsessed with reaching “the perfect state of health” through food. Unlike anorexia, orthorexia is driven by quality rather than quantity. That said, the idea of orthorexia can spark a conversation not only about an addictive behavior with food but also an addictive behavior with space.

Analemma Tower, a conceptual proposal for the world's tallest bolding ever by the artist Ostap Rudakevych and Clouds Architecture Office. Prefabricated units are hoisted to the upper limits of the troposphere. (Ostap Rudakevych/Clouds AO)

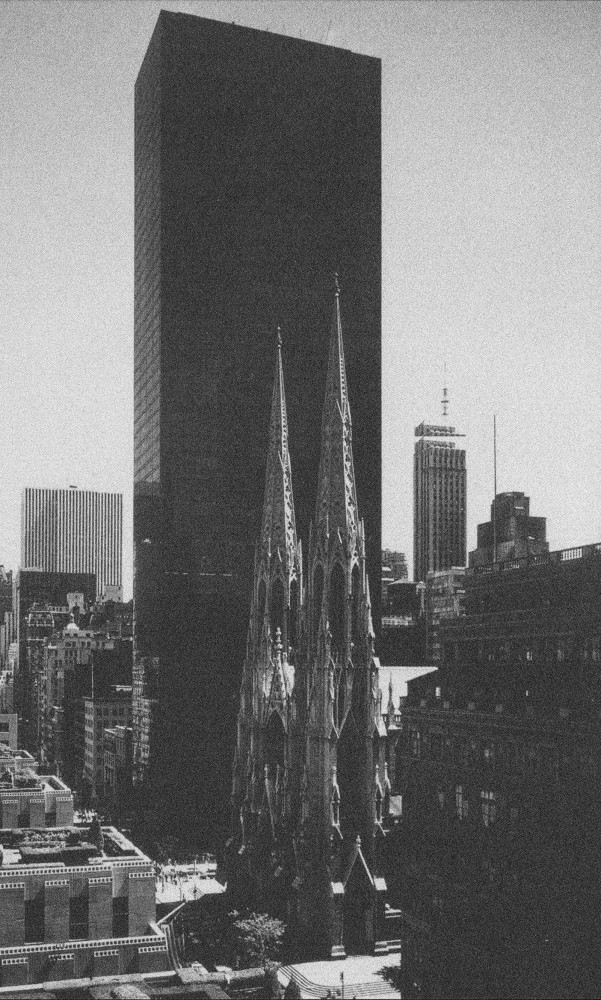

Parroting the skyscraper race in the 1930s, when the Empire State Building trumped the Chrysler as the tallest in the world, the newest additions to the New York City skyline — 432 Park Avenue, One57, and 56 Leonard, amongst them — no longer stretch an arm up, but cast an eye out. These are not corporate spectacles of height, but stacked up domiciles with an insatiable appetite for privately owned views. This appeal of owning a horizon-line view is nothing other than a desire for owned space to emulate the attitude of the horizon: a clearly defined perimeter, and an endlessly escaping limit that gives the terrain endless potential. To think about orthorexia as both a view of food and of property places its drive towards order and rightness amidst an ethical debate on humanity’s spatial relation to its environment. Both the obsessive relation to healthy eating and the realty of the horizon illustrate the correctness of an individual in a mythology of their surroundings, and make the stability of those surroundings appear as the virtuousness of a responsible lifestyle. Together they turn the “environment” into an abstraction, and show that terms like “wholeness” mistake the selfless care of an environment for the self-centered care of an individual.

An environment built

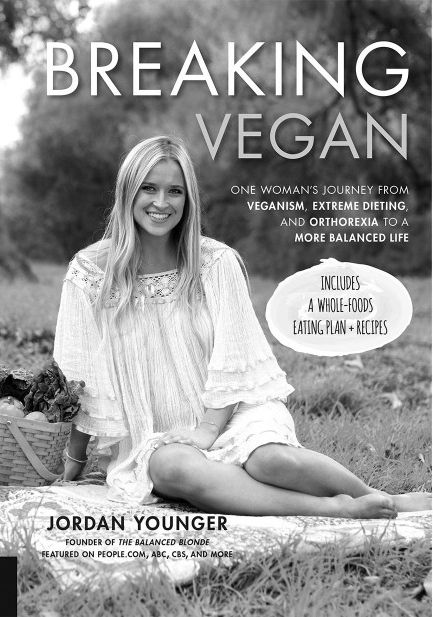

If one has a choice in what one eats, food seems a perfect medium to exercise one’s morals as an expressive lifestyle. Supposing “you are what you eat,” ingestion is not limited to absorbing nutrients, but whole alimentary ideologies as well. In 2013, alongside a flood of food blogs like Naturally Ella and Skinnytaste, Jordan Younger started her website The Blonde Vegan. Younger popularized a “healthy” identity that grew from posting on Instagram — “Avocado arugula soup! #yum #veganfoodporn” — to offering “The Blonde Vegan 5-Day Cleanse Program,” “Health is the New Black” T-shirts, and a smartphone wellness app, along with endorsing products like Vega One. Yet, little more than a year after launching, in a blog post entitled Why I’m Transitioning Away from Veganism, Younger explained that her branded health had developed into an eating disorder and driven her to malnourishment (her website is now called The Balanced Blonde). The post sparked a thread of aggressive comments filled with condemnations of her changed position, and manifesto-length defenses of the ethical values of veganism.

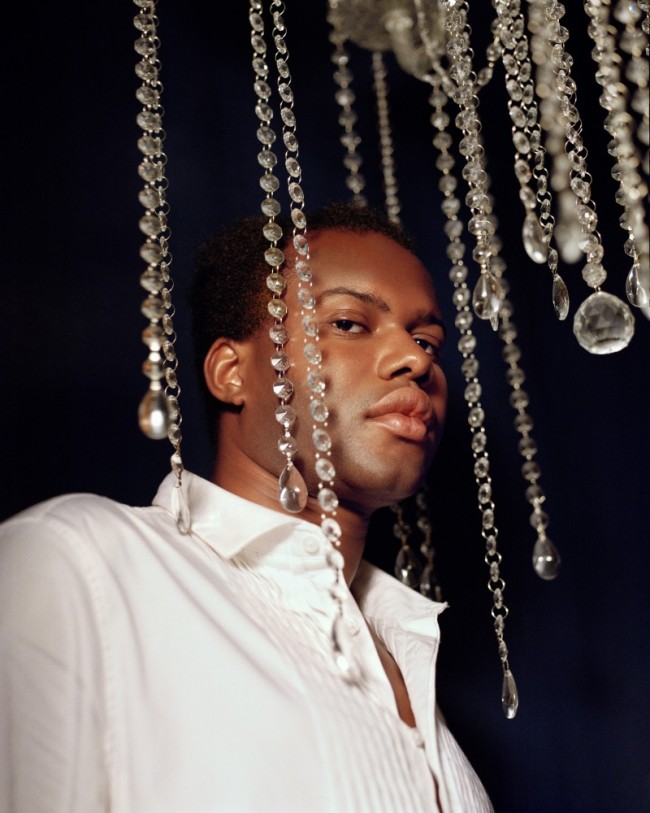

Jordan Younger's book Breaking Vegan (Fair Winds, 2015), describing the author's experience with extreme dieting: "The orthorexic reorders the messy surrounding world from the inside out, with a vanishing point of purity."

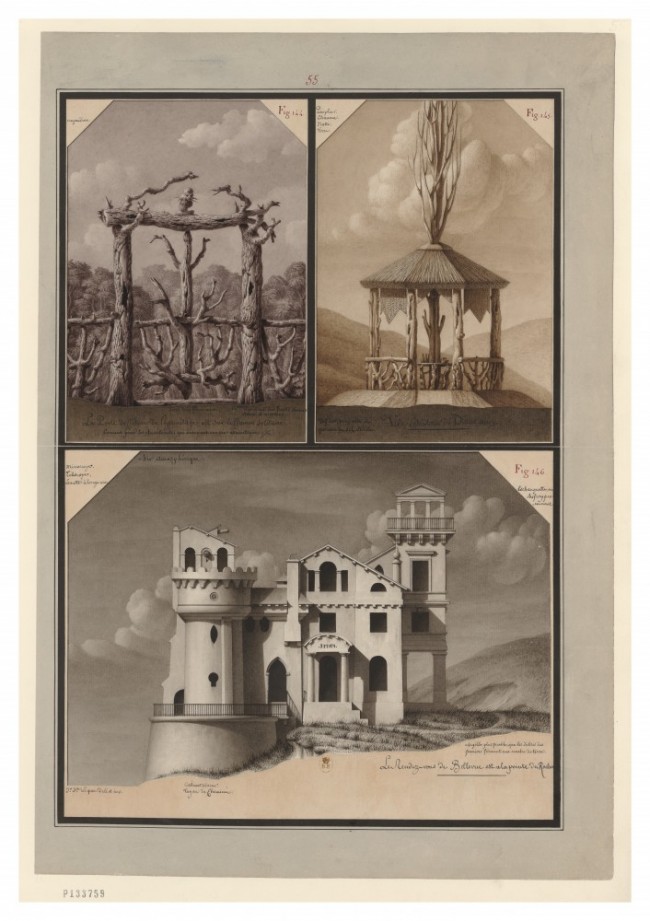

Among other “healing diets” — like macrobiotics and the Zone diet — that Bratman identifies as possible precursors to orthorexia in his book Health Food Junkies (2000), raw foodism takes on an especially mythological tone. In what would become a founding text of the natural-foods movement, Jethro Kloss’s Back to Eden (1939) states: “Since Eve first surrendered to appetite, man has been growing more and more self-indulgent.” In this turn back to Eden, the origin of all sin — with knowledge, ownership, desire, and jealousy in tow — lies in a sin with food. The garden is barred off, and entices in its unattainable purity; and so the raw foodist repents, seeking to correct humanity’s first wrong and meet the endlessly receding purity of nature in his or her own personal horizon. In its extreme, raw foodism is motivated by the purity of an individual, the environment, and the food that connects the two. In other words, if person and nature were connected in a drawing, food would act both as the vertex that pulls them together and the vanishing point, the impossible projection, of their ideal purity.

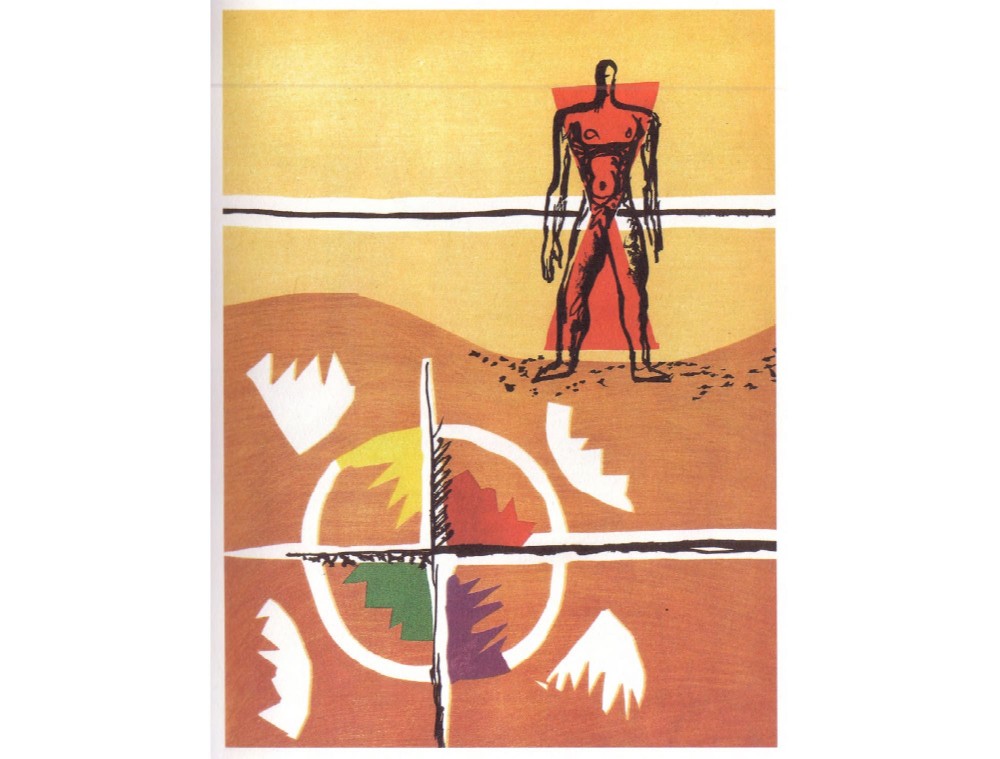

Le Corbusier, in his Le poème de l’angle droit (1955) (as translated by Kenneth Hylton) similarly joins man and nature in two intersecting lines. Rejoicing, he writes,

The universe of our eyes rests

upon a plain edged with horizon

(…) I am standing straight!

since you are erect

you are also fit for action.

Erect on the terrestrial plain

of all things knowable (…)

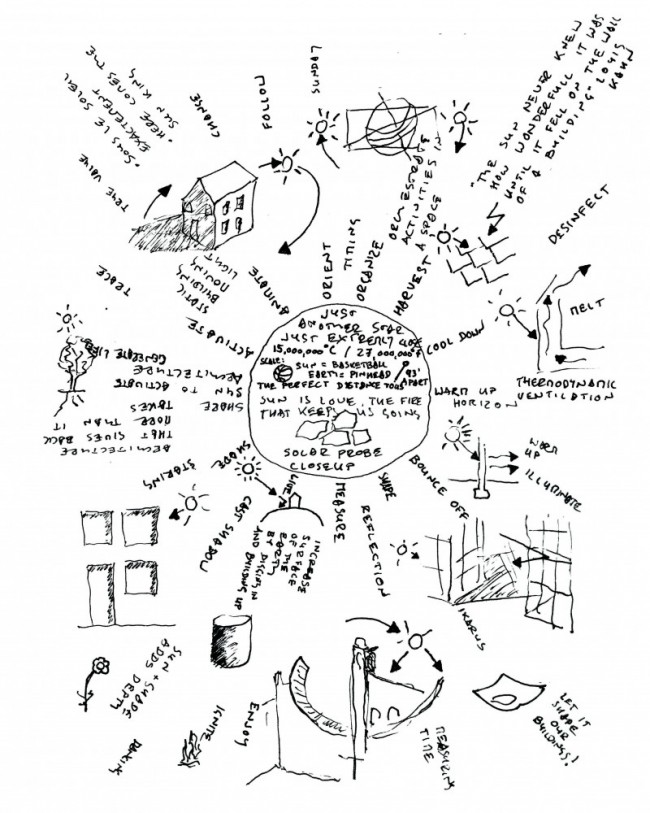

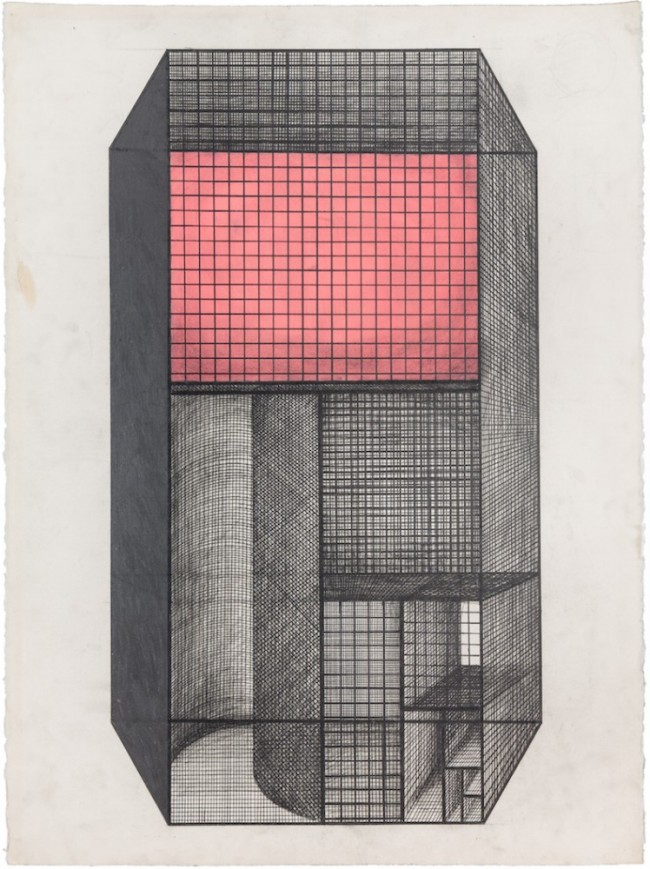

At the opening of this origin myth, one man, certainly male, stands upright with his feet firmly planted on the ground and his body shooting up to cross the horizon line. This figure is so aroused by the line that bisects him at his crotch that he becomes the origin for all grids; a new origin of all space around, tamed by his intellect and vision. For Le Corbusier, culture and nature meet in a right angle that grants human agency. In this “pact of solidarity / with nature,” the human promises to clear “the path of thorns,” and to construct his own coordinates of purity; in other words, to build the idea of an environment where ordering nature is not only a path toward human purity, but also our custodial responsibility. Be it for the raw foodist or Le Corbusier’s modern man, the orthorexic solidarity with the environment depends on correctly rebuilding it. As Le Corbusier introduces architecture to his creation tale, he describes each concrete floor slab as a duplication of the horizon line. As an extreme orthorexic, and no less anthropocentrist, Le Corbusier sets up a mirror to what we might more casually call the built environment. And accordingly, in this environment-as-it-is-built, we still hang off the myth of a plumb bob and relax in a bubble floating in the middle of a tube of yellow fluid. Here, humanity meets nature in a tautology: one builds a level earth, and then uses a level while standing on it.

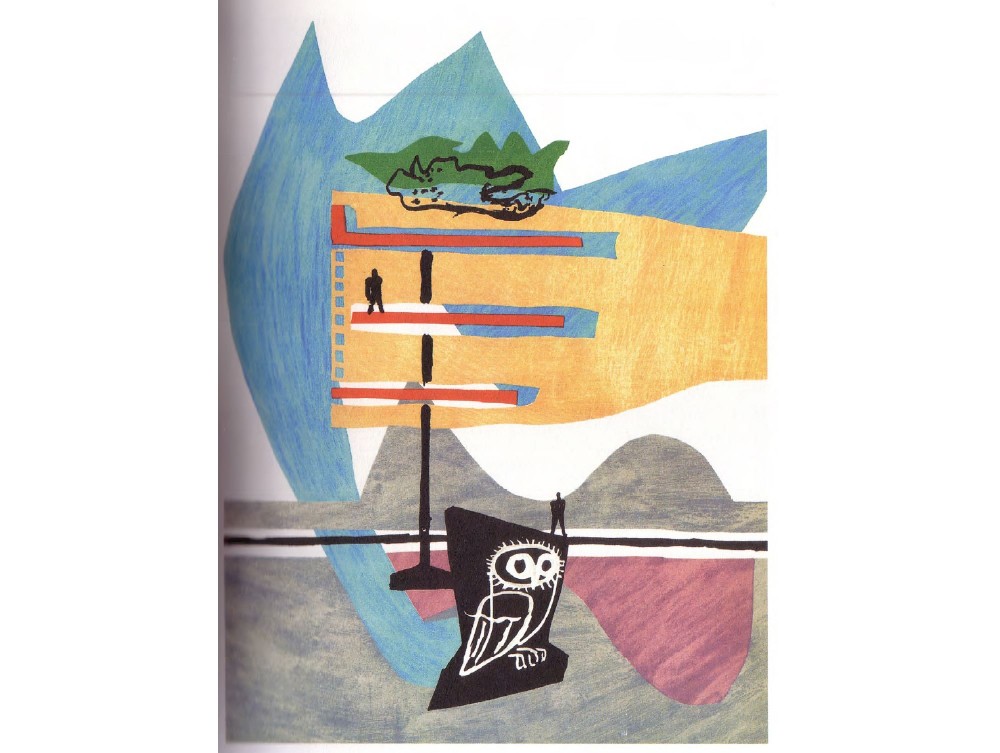

A painting from Le Corbusier's Le Poème de l’angle droit (1955). (Fondation Le Corbusier/ADAGP)

Resting on a horizon that is both pure and endlessly receding, the myth of Modernism and diets that set a path towards orthorexia offer similar ways of measuring not only a spatial relation to nature, but also its apparent moral goodness. The “self-proclaimed ‘objective truth-seekers’” who authored Nature’s First Law: The Raw-Food Diet (Stephen Arlin et al., 1998) speak of the human body as a machine fed on raw materials, and distinguish this “true body” from a “mutant ‘false body.’” Similarly, 30 years before Le poème de l’angle droit, Jeanneret and Amédée Ozenfant wrote The Right Angle (published in L’Esprit nouveau in 1923), a manifesto of sorts on the “orthogonal spirit,” insisting that “only one right angle,” as a “symbol of perfection” and the “origin of human activity,” will cure a society deluded by the oblique’s “expressive dynamism of instability” and “unresolved anxiety of spirits.” Pinned against the oblique, the orthogonal spirit disguises its bias with its own definition of purity. And by the same tenor, orthorexia nervosa “disguises itself as a virtue,” as Bratman explains. Anorexics “may know they are harming themselves, but orthorexics feel nothing but pride at taking care of their health in the best possible way.” Following a guide of quality living, orthorexia excuses itself from its own bias, and hears any criticism as perplexingly misled. Orthorexia as a “self-imposed deprivation,” as Bratman insists, “usually looks perfectly sensible from within.”

A painting from Le Corbusier's Le Poème de l’angle droit (1955): “For Le Corbusier, culture and nature meet in a right angle that grants human agency.” (Fondation Le Corbusier/ADAGP)

From a place of inner sense, orthorexics rebuild their surroundings as controlled terrains of righteousness. As she describes in her memoir Breaking Vegan (2016), Younger restricted her diet as a way to “control any challenges that came (her) way ...” Furthermore, Younger explains that her vegan diet and “passion for health” acted as a mode of self-expression between herself and those around her. Echoing the Corbusian figure that rebuilds its orthogonal relation with the horizon line in each successive concrete floor-slab, the orthorexic reorders the messy surrounding world from the inside out, with a vanishing point of purity. This mythic setting reflects a control one can identify with, and a correctness one feels responsible for. Identifying with a terrain of righteousness that one has personally built, any judgment of rightness promises a perspective that only illusively escapes its subjective body.

In a “love affair with veganism,” or with other healing diets, as Bratman notes, one may become “addicted to a feeling of physical lightness” — the desire to transcend one’s own body, social relationships, and physical context. Like an “angel of light,” the orthorexic wants to float “free from the weightiness of life on earth,” and in a malnourished high of superior grace, see his or her place in the world as if objectively, from above. In this angelic venture up, one might imagine seeing not only the horizon, but also the whole earth, the relationships between its parts, its ecology, and its history of faults that have pushed us further and further away from the purity of a turn “back to Eden.”

Analemma Tower, a conceptual proposal for the world's tallest bolding ever by the artist Ostap Rudakevych and Clouds Architecture Office. (Ostap Rudakevych/Clouds AO)

Living with horizon-line views

For city-dwellers, a view of the horizon is a rarity. We find glimpses upon hills of gridded streets, on promenades along the city’s margins, and in the majestic sites of tourist traps. Roaming the streets, this imaginary line is so scarce that, if we were to take seriously the remark by the German phenomenologist O.F. Bollnow in his 1963 book Human Space that “the horizon ... belongs ... inseparably to man,” we would find ourselves less than human. On the other hand, in new luxury high-rises, grandiose views replace as many walls as possible. Along the midriff of each apartment is a horizon for its tenant to privately own. It is no surprise that, rising above Midtown’s other pinnacles of wealth, 432 Park Avenue, with its lux-superiority and unimpeded horizon-line views, has been dubbed the middle finger of Manhattan.

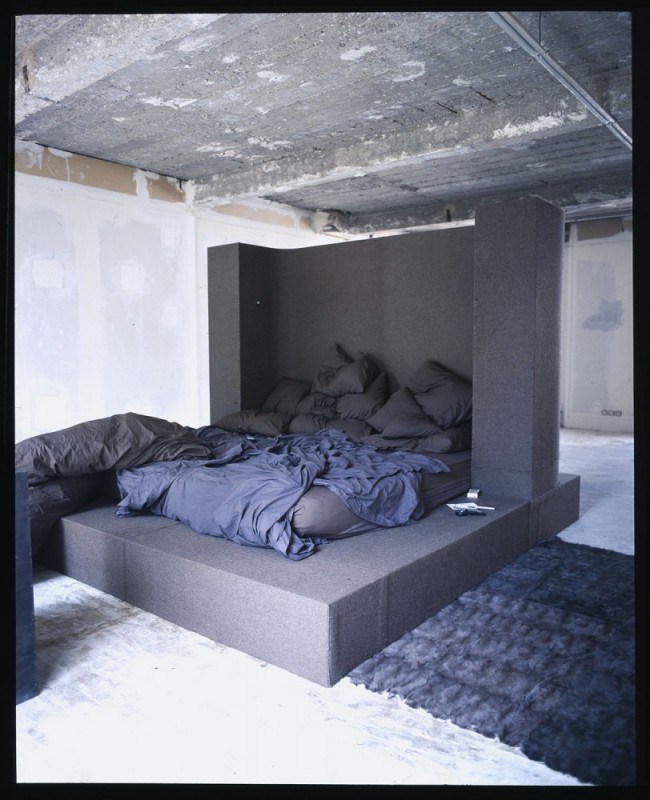

But to what degree can a horizon line be owned? And if it can be, how is it sold? As the renderings of 432 Park suggest, one can breakfast with the horizon, bathe with it, or go to bed with it. Yet from the penthouse of 432 Park, at a height of 1,396 feet, the relation to the horizon is not as digestible as Le Corbusier might have liked it to be. In an expansive view like this, one gets lost. As Warren Estis — who lives in the 86th-floor penthouse in Trump World Tower — said earlier this year when interviewed by The New York Times, trying to mask any hint of jealousy towards the residents of 432 Park who now split his view, “At a certain point, you’re too high ... Up there you lose the effect. You have to walk to the window to look down.” Accordingly, luxury condominiums have found ways to give their residents a feeling of control over these views. With the shift away from the dictum “location, location, location,” real-estate language now itemizes views — “You can have park and river, or river, bridge, and bay.” And furthermore, to the credit of 432 Park, marble-framed windows have replaced floor to ceiling glass, parsing one’s view into 100-square-foot color-field canvases that can be bought and sold. Driving this desire to live higher and higher up is the marketing of one’s relation to an environment that is an abstraction. As an abstraction it can be at once a possessable object and virtuously pure.

Analemma Tower, a conceptual proposal for the world's tallest bolding ever by the artist Ostap Rudakevych and Clouds Architecture Office. Prefabricated units are hoisted to the upper limits of the troposphere. (Ostap Rudakevych/Clouds AO)

The “blessing” of privately owning a horizon line apes the mindset of the orthorexic in his or her control of a worldview. Both are abstractions and both create terrains of righteousness that celebrate their beholder as ethically pure. Bratman explains that along with the “iron self-discipline” and “self-condemnation for lapses, (and) self-praise for success,” the orthorexic often feels a “conceited superiority over anyone who indulges in impure dietary habits.” A feeling of “pride-worthy willpower,” as Younger calls it, is a source of identity and a source of dignity, justified by a hallucination of ethically driven control. Surrounded by the environmental maladies of the meat industry, deforestation, monoculture, and a myriad of pollutants, a corrective diet that reaches for purity reframes one’s relation to the world as benevolent. Through one’s own self-restraint, one feels personally responsible for the salvation of the environment. And on this self-sacrificial path, one’s role is virtuously indomitable as the redeemer of all others’ impurities.

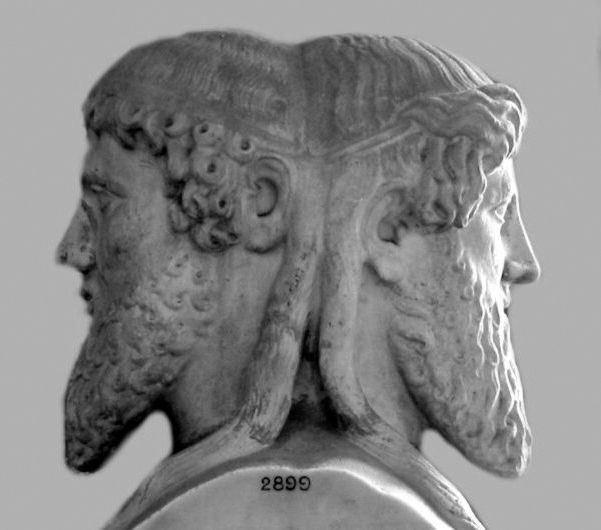

Roman deity Janus, who looks to both the future and the past: "A building like a stack of Janus heads too farsighted to sense a chin above or a nose below."

From the lobby of 432 Park, one enters the residential elevator, taps a key, and is brought directly home. At home one has a personalized view; and unable to see the neighbors above or below with views that would approximate to one’s own, that view seems ever more inimitable, as if emanating from a free-floating dot in the middle of the sky. 432 Park is a stack of Janus heads, each with eyes too farsighted to sense a chin above or nose below. By comparison, One57 stands as a set of interlaced towers; so, from a living room facing Central Park or a bathroom facing Midtown, one can look to the left or right and see a neighbor’s window. Compared to 432 Park, One57 fails to sell its horizons. Sights of neighbors and other residential towers are not just pestering breaks in a horizon-line, but the impediment to entering into a private relationship with it — to domesticate it and identify with its abstract purity. In the silence of a home stabilized by oscillation dampers, barred by keyed elevators, and insulated by high-performance windows, the orthogonal horizon etches itself along the glass, drawing not only a foundation for the sky, but a mighty lid pressed over the din of the Earth. Alone, one feels boundless pride for having calmed the world by welcoming it into one’s home.

Color field window frames on the 82nd floor of 432 Park Avenue: “A palatable slice of Earth's magnitude hangs there like wallpaper.” (Timothy Simonds)

Let’s look at the relation between luxury condominium real estate and horizon-line views another way. If there were no surrounding obstructions at ground level, one could spin around and see a horizon line about 18 miles around, equivalent to about 0.07 percent of the Earth’s circumference; in 432 Park’s penthouse, however, with one’s nose pressed to the glass, one can scan over a horizon that spans 0.53 percent of the Earth’s circumference; and stepping back to the middle of this full-floor apartment, one can turn all around to see a horizon-line that stretches to just over one percent of the Earth’s circumference. This palatable slice of the Earth’s magnitude hangs there like wallpaper, a part-world object that has been apportioned by private ownership. When one considers that a penthouse resident of the Burj Khalifa can experience one sunset on the ground and then a second by taking the elevator directly up to their home, it seems obvious that a feeling of control with respect to the environment is packaged into the private ownership of a domestic worldview. Pure, abstract, and ordered, the extension of domesticity into the horizon quiets one’s feelings of responsibility towards the surrounding world. With the purchase of a worldview, one blinds oneself to one’s own narcissism, and appoints oneself as benevolent overseer.

Color field window frames on the 82nd floor of 432 Park Avenue: "A palatable slice of Earth's magnitude hangs there like wallpaper." (Tim Simonds)

Wholeness

Whether from a sidewalk on Fifth Avenue or in traffic on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, one can imagine with a flicker of the fingers the windows of 432 Park repeating themselves relentlessly, continuing up until they disappear beyond the atmosphere. 35,000 feet up in this fantastical annex, the visible horizon starts to curve. From 250 miles above the surface, that curve bends into a tight arc. If the real-estate prices of 432 Park were in fact correlated to the length of this arc, a half-floor apartment with views at this elevation would cost about 1.4 billion dollars (a bargain considering the 3-billion-dollar yearly maintenance bill that the U.S. alone pays for the International Space Station). And at a certain point, as one moves farther and farther up, farther and farther out, this curve snaps in on itself. The horizon becomes its circle, encapsulating the Earth as one whole object.

Analemma Tower, a conceptual proposal for the world's tallest bolding ever by the artist Ostap Rudakevych and Clouds Architecture Office. The massive tower would be suspended by a comet in geosynchronous orbit. (Ostap Rudakevych/Clouds AO)

In 1966, NASA released the first photograph of the Earth as a whole object. In the context of the 1960s, this gesture of turning our eyes back on Earth influenced two opposing mindsets with regard to humanity’s relation to nature. On the one hand, the image of Earth as an object became an icon for the environmentalist movement. The Earth looked finite and expendable. With the help of Stewart Brand’s multi-volume Whole Earth Catalog which began to appear in 1968, and the first Earth Day in 1970, this image became a tool to raise the consciousness of a worldview in which “humanity was destined to destroy the Earth and itself unless it mended its ecologically unsustainable ways,” as William Bryant notes in his 1995 essay, The Re-Vision of Planet Earth. On the other hand, looking back on Earth symbolized a frontier spirit, with its own colonial aroma. The image was “compelling evidence that ‘man’ was destined forever to explore and conquer nature,” according to Bryant, and it was precisely the adoption of this dual image that dampened and distorted the initial intentions of the environmentalist movement. As Bryant explains, by Earth Day 1990, the image of whole Earth had become an abstracted “veneer” of green and blue.

The idea of “wholeness” suggests the sense of something both untouched and indisputably perfected. It promises the complete entity of a person, balancing mind, body, and spirit. To that entity it fuses nutrition. And, to that already agglutinated identity-sustenance, it adds an image of earth. In wholeness, individual = food = environment. Furthermore, being untouched, this worldview removes any human-tainted bias from the equation. Following a century of industrial-scaled food manufacturing and a wealth of adulterated-food fraud, the flexibility of the term “wholeness” seems like a remedy. The term’s flux lets the impurity of the environment be the impurity of a society; in the words of Ann Wigmore, as quoted in Nature’s First Law, “Where green life has been effectively extinguished, in inner-city ghettos and prisons, mental illness and violence are commonplace.” And at the same time, as Nature’s First Law also emphasizes, this sense of wholeness hands the control of the environment over to the individual: “The Raw-Food Diet…transforms the planet by transforming you.”

Through wholeness, humanity’s relation to nature drifts to the private sector. As the narrative goes, advertising became branding, and through branding corporations could capitalize on a “green” consciousness. With the creation of corporate identity, products became more relatable, each only a part of a nexus of many swimming bits that make up a lifestyle to identify with. Bryant makes it wonderfully clear, explaining that on Earth Day 1990,

“consumer capitalism moved in to colonize new territory, build a ‘green’ marketplace, and so inoculate itself against the disease of anti-consumption… (T)he ecologically conscious individual was converted into the ‘green consumer,’ who did not have to practice environmentalism so much as perform it through ‘lifestyle’ choices pivoting on the purchase of ‘Earth-friendly’ products.”

With the Earth in the market, whole Earth could be sold with whole food as one apparently virtuous lifestyle of whole health. What better and more convenient way to feel like one has cared for the environment than to do something within one’s own control? Recycle, plant a tree, buy an organic apple, unplug your iPhone charger, and, in an act even more oddly associated with wholeness, care for your body by expending energy at the gym. A juice detox with a brand like Rawvolution, Urban Remedy, or Moon Juice speaks not only to the rejuvenation of a digestive system but a general cleanse, from the rot of poor social conditions to the guilt of colonizing celestial bodies. Your purity is Earth’s purity. In an era of branding that conflates the insides and outsides of life and style, individual and environment, you care for a world around you that is the extension of a portrait of yourself.

-

Tim Simonds, Janus Stacks. 2015–16. Potatoes, cotton string.

-

Timothy Simonds, Janus Stacks, (2015–16). Potatoes, cotton string.

-

Timothy Simonds, Janus Stacks, (2015–16). Potatoes, cotton string.

In the “sky of an I”

In a reverse camouflage, the homeowner and the orthorexic find their place. Through wholeness, orthorexia and high-rise real estate idealize a relationship between humanity and the environment that praises the individual and its control. By controlling this worldview, one sees in one’s surroundings a reflection of oneself that appears selfless. Furthermore, posing this selflessness as a pride-worthy part of one’s identity, this worldview effaces concern for what is beyond one’s immediate control and puts in its place an unbreakable tie between responsibility and capital. In other words, the enticing view of caring for a larger whole is indistinguishable from its opposite: environment becomes private property, care becomes responsibility.

Wholeness turns a signature quote of the environmentalist movement on its head. A purported 1855 letter from Chief Seattle of the Duwamish tribe to President Pierce contains this rebuke to the U.S. government’s forceful purchase of land: “If we do not own the freshness of the air or the sparkle on the water, how can you buy them from us?” Under capitalism, we are all orthorexics, needing to order our surroundings, demarcate the limits of property, and feed its potential growth, in order to feel responsible for it: one is whole with an environment that one owns, controls and takes responsibility for. In short, in wholeness is the general hollowness of selfless care.

In the search to disperse one’s individuality one finds comfort and a pat on the back for solipsistic wholeness. One measures one’s own virtue by one’s connection to a horizon of purity one has perceptively built. As philosopher Cornelius Anthonie Van Peursen explains in his essay The Horizon (published in the 1977 anthology Husserl: Expositions and Appraisals, edited by Frederick A. Elliston and Peter McCormick), a horizon “is the translation of man into the world” because it “accompanies man like his shadow” — it is an image that is defined and personally attached, while at the same time outside of the self and moving. But to borrow a term from Madeline Gins’s 1994 book Helen Keller or Arakawa, in a “sky of an I” there is no horizon. There are no shadows; there is no ownership; there is no responsibility; there is no tie between I-food-world-and-eye. There are only transitions.

Text by Timothy Simonds.

Timothy Simonds is an artist based in New York. He holds an M.A. in Performance Studies from Brown University. Simonds teaches between architecture, humanities, and sculpture at Pratt Institute and has shared his writing at Brown University, Princeton University, and the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland.

A version of this essay was published in PIN–UP 21, Fall Winter 16/17.