INTERVIEW: Photographer Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. Talks Interior Lives

New York-based photographer Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. creates images of people that are often partial, oblique, even obscure. They depict individuals or interactions not through faces, but through the construction of interior life, and, in many instances the depiction of literal interiors. While regularly in the pages of magazines (including PIN–UP) or hung on walls, when presented in galleries, Brown Jr.’s work is also often presented as more objects, with cut wooden overlays, irregularly shaped frames, or even sculptures set in front of light-boxes. His pictures are architectural in both the most direct and expanded senses of that word. Brown Jr. has recently created new work for MIEN, a digital exhibition and fundraiser organized by design studio TRNK and its co-founder Tariq Dixon. During Pride Month, MIEN brings together seven queer artists of color who challenge the status quo of LGBTQ+ portraiture. Brown Jr.’s contribution depicts two figures in a relationship at once inaccessible and intimate, which bears a title as extended caption, a sort of prose poem that begins “Breath tucks in and weighs the eyes closed.” Posters will be available for purchase until June 30th, with proceeds going to the Ali Forney Center to support homeless LGBTQ youth. (The exhibition also includes work by another frequent PIN–UP contributor, Dorian Ulises López Maciás). Musician, DJ, curator, and native New Yorker Tony Jackson Jr. (aka Skype Williams), spoke with Brown, Jr., about experiences of domestic space, the relationship between photographer and photographed, legacy, memory, and music.

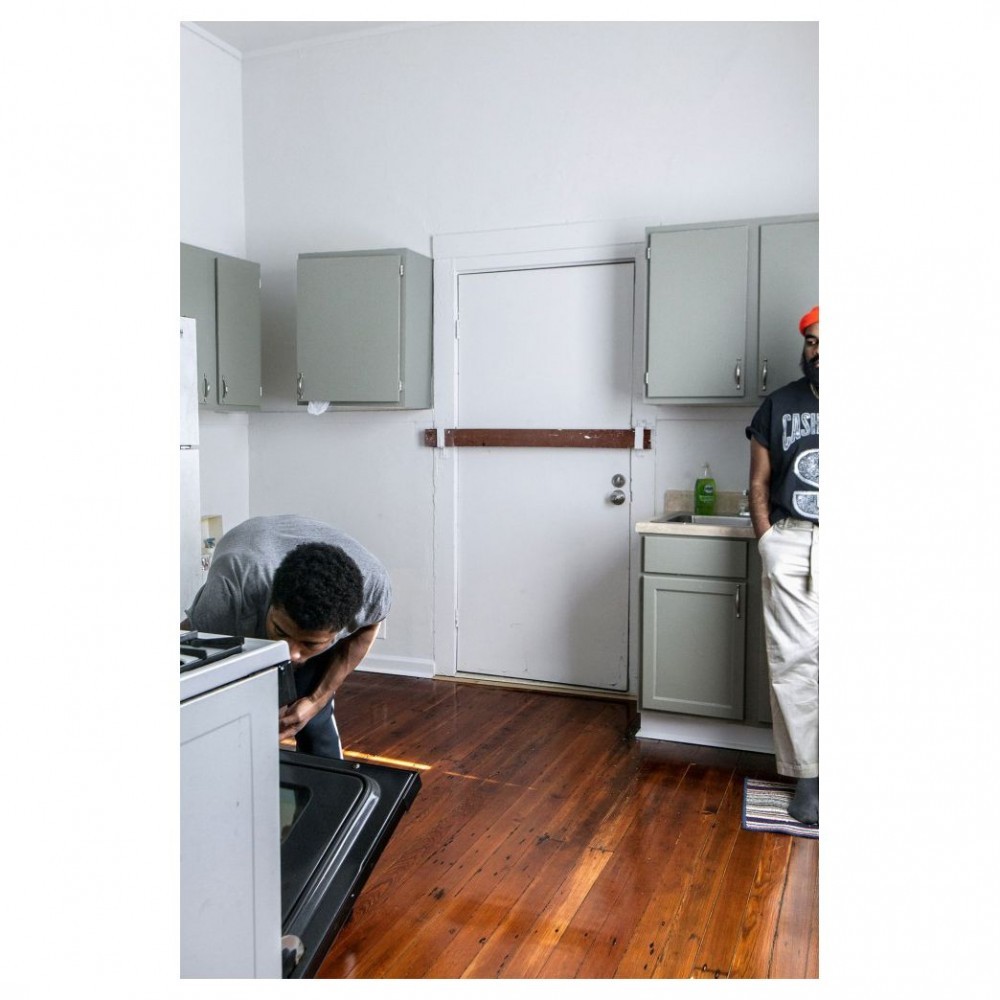

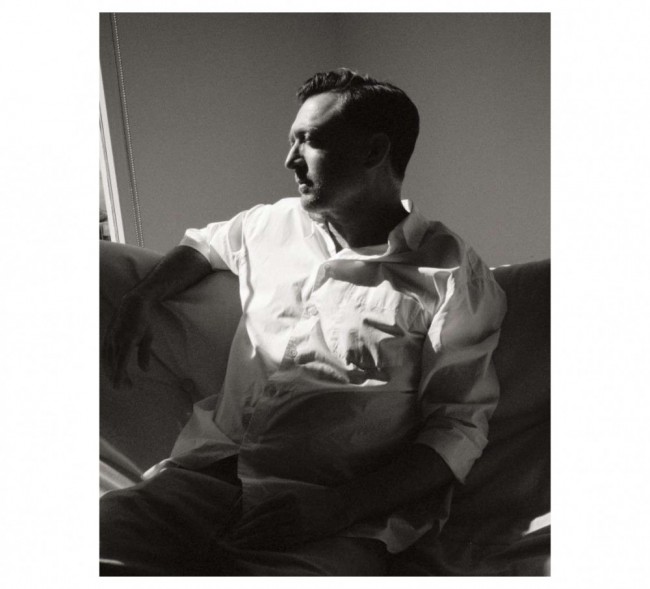

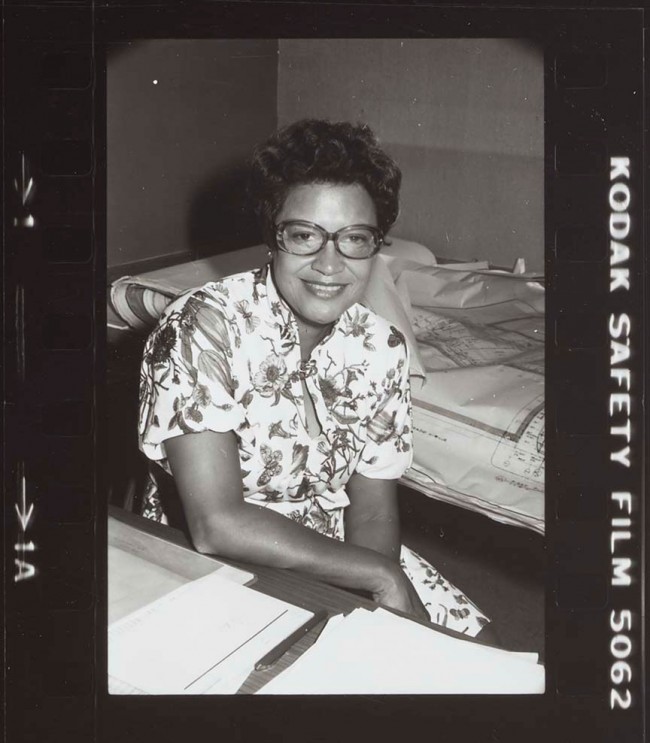

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Look at how much we look alike, (2018); archival pigment print, 23 x 32 inches.

Tony Jackson Jr.: Being in video chats, like we are now, because of social distancing, has been cool in a way — getting to see how people are positioning their cameras and what they want to show. If you go to somebody’s house, you see everything, but when you see somebody through a camera, you’re seeing what they want you to see. What area of your house are you gravitating towards for video calls?

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.: I’m in an unusual situation where I work as a caretaker for a historic house museum in Queens. In exchange for basic maintenance and basic groundskeeping of the house, I live there. The first floor is open to the public. It contains all the information related to the man and his accomplishments and whatnot. Then, the second floor is my living quarters, and then the offices for the two directors and various interns. My space is sectioned off. It's private. It's outfitted with all the things that a normal apartment would have. The house receives a great amount of sun in pretty much each of the rooms throughout the day. This was supposed to be temporary, but I’ve been offered the position permanently, so now, there's the possibility for that relationship to deepen in that this is my space for as long as I'd like to keep it and as long as the museum is operating. Already, the house has become a friend of mine. The living room is my favorite place in the house just because of its expanse. Funny enough, the text for the photograph that is included in the MIEN exhibition is an abstract text where I was thinking about my productivity during the day. It was a direct reflection on walking into the living room and literally feeling euphoria, amidst all of the possibilities that are available to me just by way of waking up.

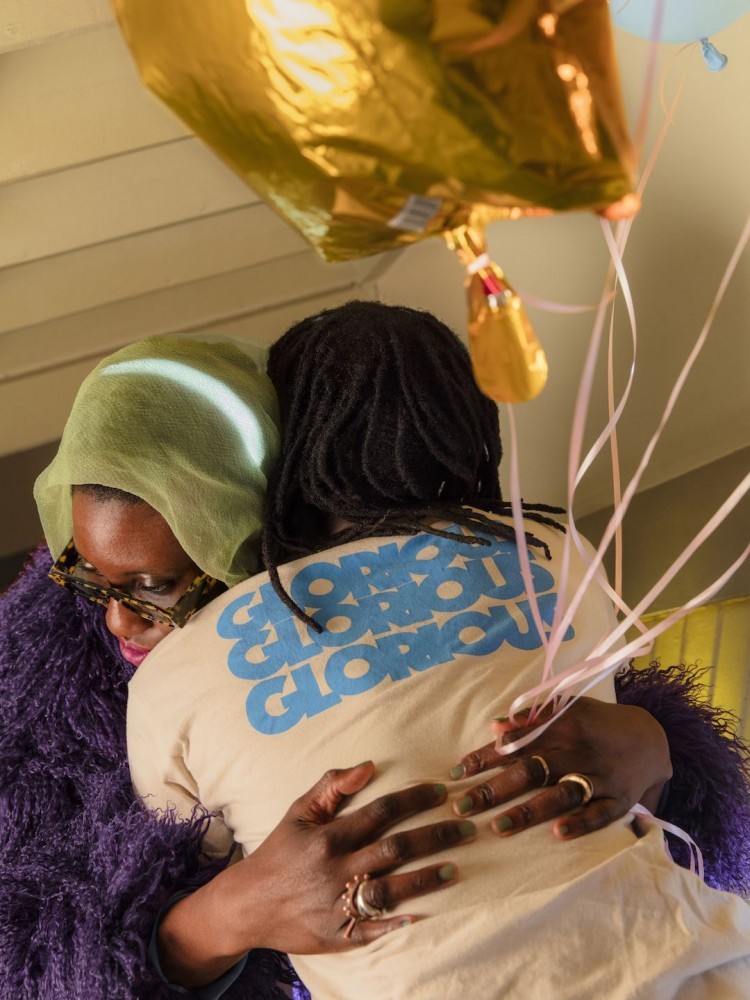

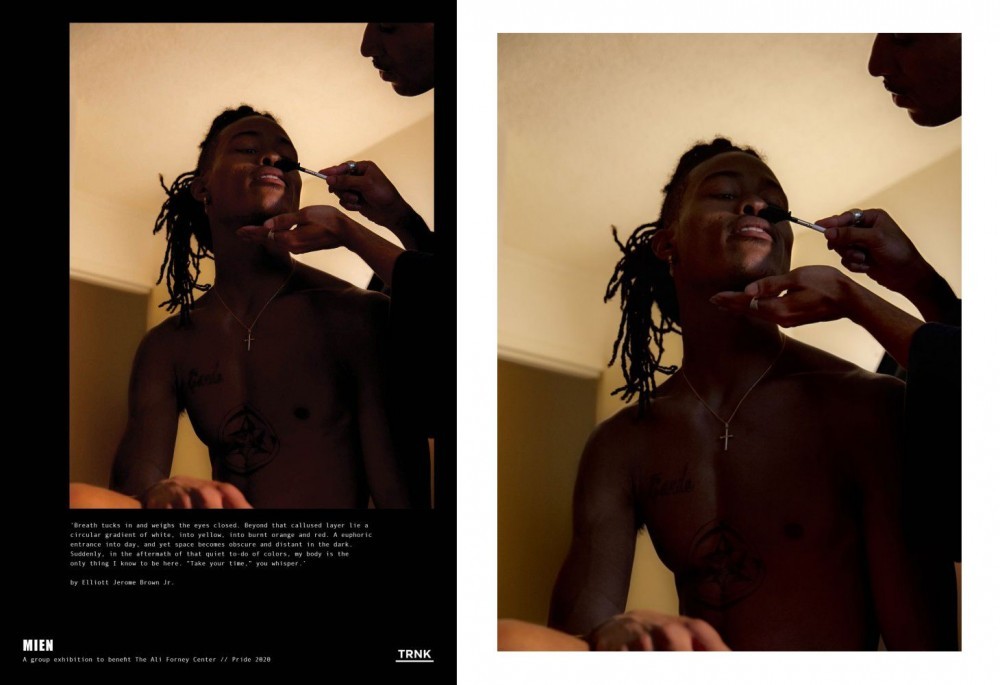

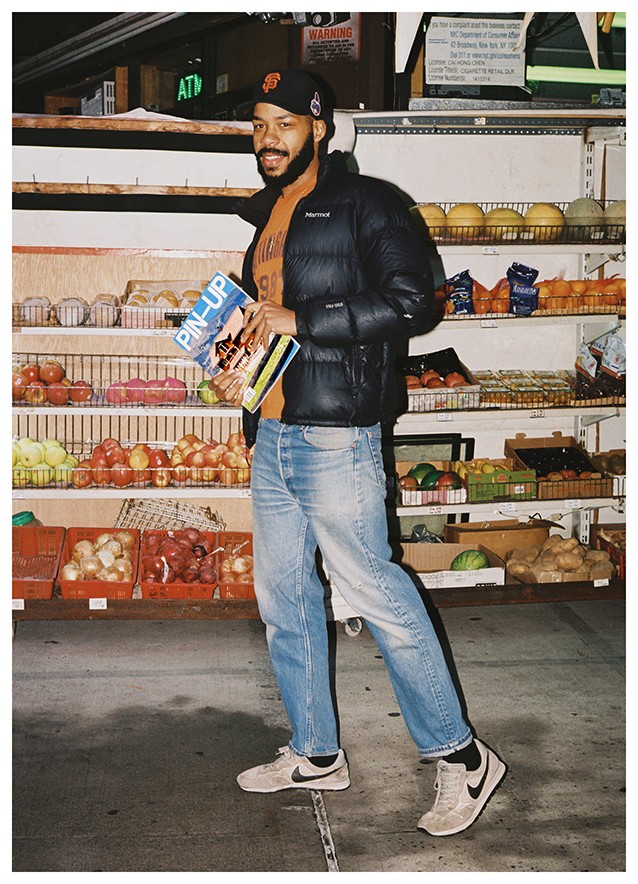

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Breath tucks in and weighs the eyes closed. Beyond that callused layer lie a circular gradient of white, into yellow, into burnt orange and red. A euphoric entrance into day, and yet space becomes obscure and distant in the dark. Suddenly, in the aftermath of that quiet to-do of colors, my body is the only thing I know to be here. “Take your time,” you whisper., 2020. (Courtesy of the artist and TRNK.)

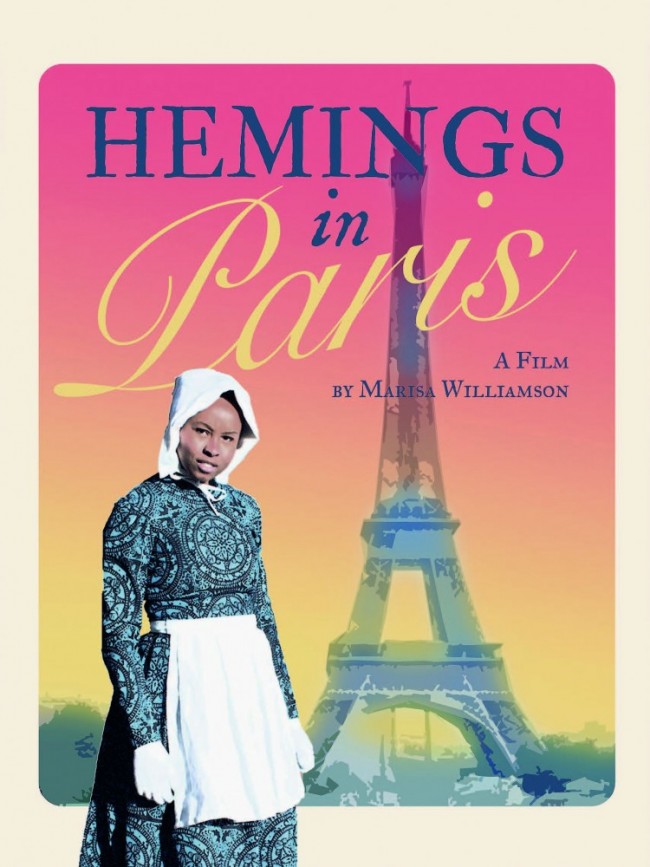

A poster for MIEN, a Pride Month exhibition organized by TRNK and Tariq Dixon to benefit the Ali Forney Center.

You’ve said before that you feel like you have a responsibility to the people that you photograph. I feel like if you’re photographing friends, they get it. What does that look like when working with people you don’t know, for people who don’t immediately “get it”? How did you go about depicting intimacy in the photograph for the MIEN poster?

The reference for that image was a screenshot of these two guys who were having sex with each other that I likely found on Twitter and the top was so entranced with something that was off the camera. I assume that it was a mirror. It looked like they were in a bathroom space. I was fascinated by how transfixed he was by his impact on this person, but it was a very confident, tough but very soft and sensitive interaction between the two of them. When I was thinking about someone who might be able to convey that, this person came to mind almost instantly just because of how they had shared themselves on Instagram, which is where I’d only really seen him. I told him about the idea. When I asked him, I said, “Choose someone to interact with that you would feel comfortable with," as opposed to me being the person who makes the selection. It was just one scene. What we're seeing here is one image, and it was actually an outtake but I liked it. The erotics of the scene are important to me, but it's also important to honor the introspective way that might bring both people together. In addition to this interior space, in addition to this bodily space, overall, what I need to get at in making photographs is what is the cerebral space? What's the intangible space? How can I make a photograph of that?

I think it’s interesting that you talk about the intangible spaces because I was thinking about black interiors in a physical aspect, but also you’re thinking about the aspects that aren’t physical. Often you see black spaces in a political context in a way that’s really flat. But to photograph people in intimate spaces is sacred. How do you balance or combine capturing that interior, mental landscape, and that physical interior space?

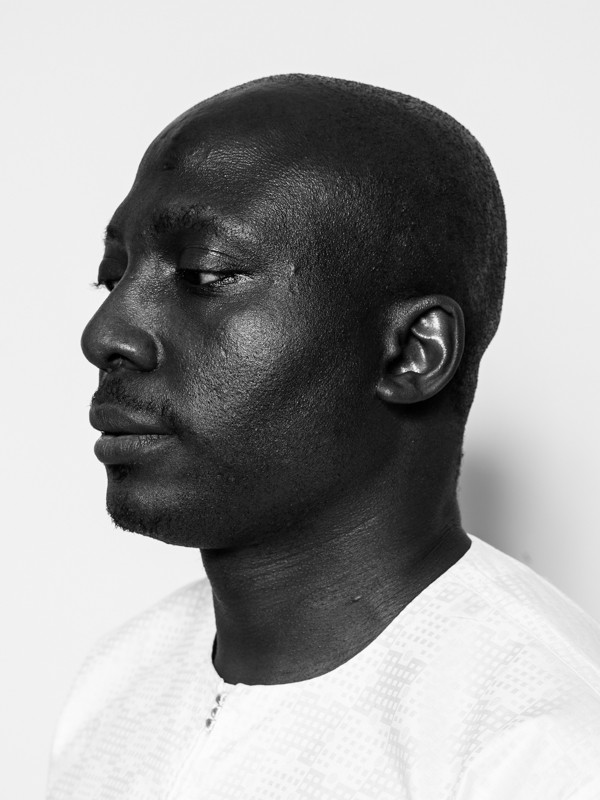

I definitely think the interior space of an individual is primarily communicated through the full package experience of the photograph itself: How is the photograph composed? What is the lighting doing? What does the lighting in the composition make available in terms of being able to orient yourself to the image as a viewer? I think because I insist on these obstructed views of people, with this particular image, the shadows do a lot of that work for me and then the margins do the work where you're not fully seeing this character. This person is slowly appearing to you out of the light. I think making photographs like that, for me, helps articulate the interior space of an individual as opposed to making a portrait.

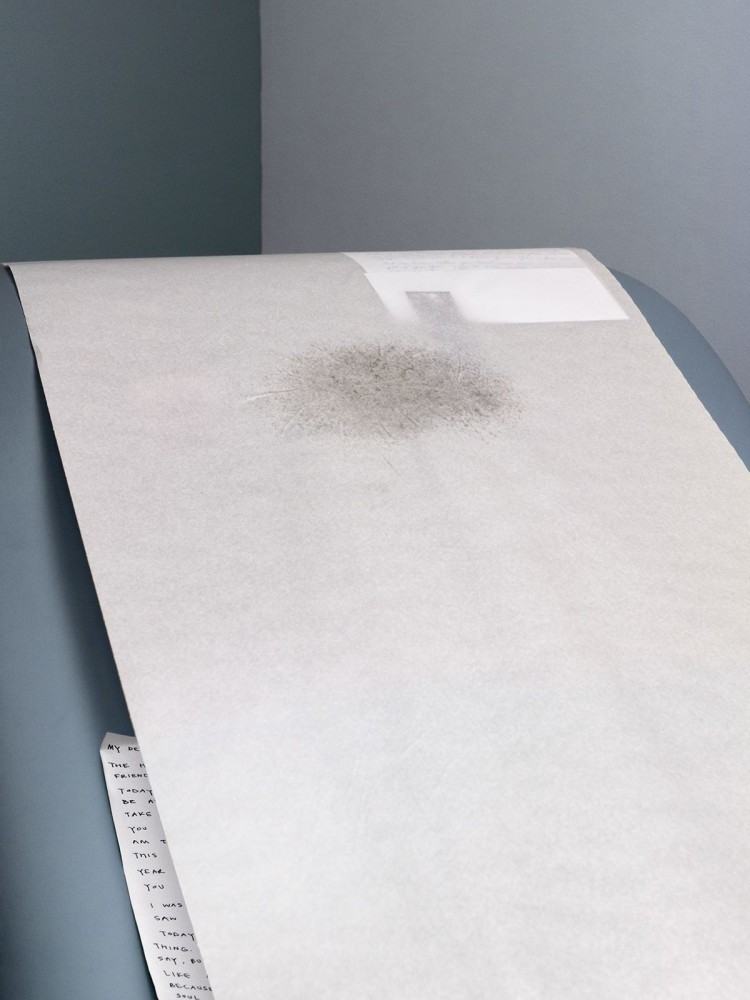

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., The sun appears to rise at the wrong time, kneading black into blue. Sometimes I mistake car lights passing through my window for an attack, for something with the capacity to tear a break in the glass., 2018. (Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.)

I grew up in a lower class neighborhood in Queens. When people photograph black interiors that are familiar, that look like what I’ve seen, it’s surreal to see that in a gallery or in a magazine. Because usually, if it's through the lens of a white person, the feeling that they want the viewer to feel is danger or sex. It’s not all these other emotions and things in between. Do you think non-black people should photograph black people in black spaces, in their homes? They’re going to, but…

Yeah, they are going to. Look. I would really prefer for people who are not black to not make pictures of black people, period. I often wonder what blackness means to white people in their images? So often, white people will make images of black folks and they will do it under the guise of “I’m facilitating a space for these underrepresented people's voices to be heard.” When you are an oppressed person, you have to not only live your life, but you also have to be smart enough to understand your oppressor. I find white people to use black people as a moral compass of a sort when really, they could be investigating this need for ignorance, this need to assume power over one another, over other people. They could be doing that just well and fine amongst white people. I don’t think white people need to be concerned with giving black people voices.

Do you think that extends to non-black people of color?

Yes. But I think that there is such a thing as solidarity. Like the Yellow Jackets Collective, I went to school with all of them, at NYU. I’ve watched them and watched the work that they do. I watch how they orient themselves in relationship to anti-blackness and doing the work to undo it, and it is specifically from their perspective as Asian people and then the diverse perspectives within that. They are very intentional about how they take up space in relation to these issues so it doesn’t look like, “Hey, let’s do a photo shoot with some black trans girls”. It looks like “How do we actually talk amongst ourselves as Asian people about how we participate in and perpetuate anti-blackness?” That is useful work. We don’t need y’all to be making pretty images of black people.

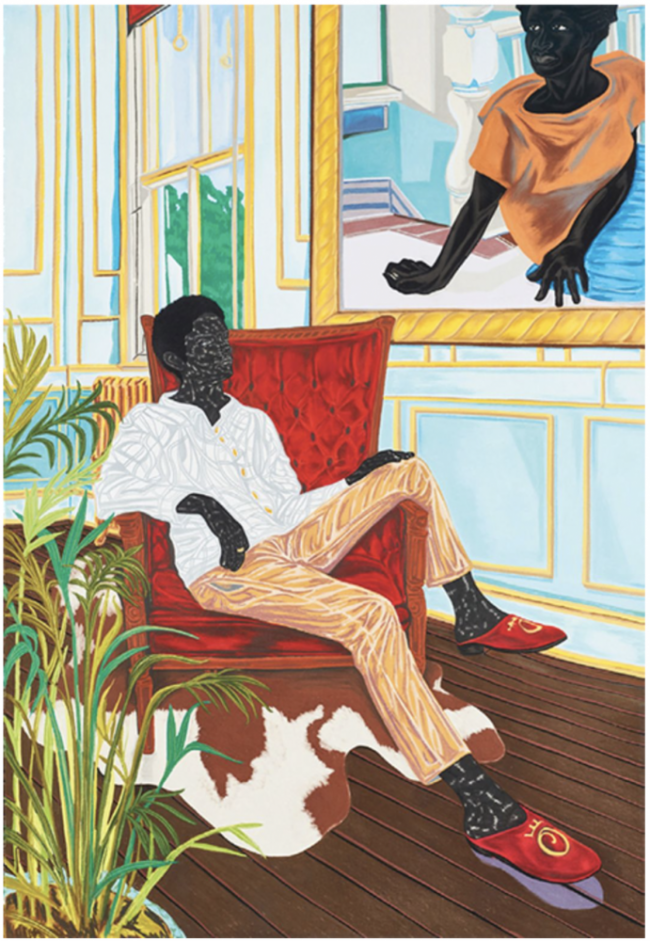

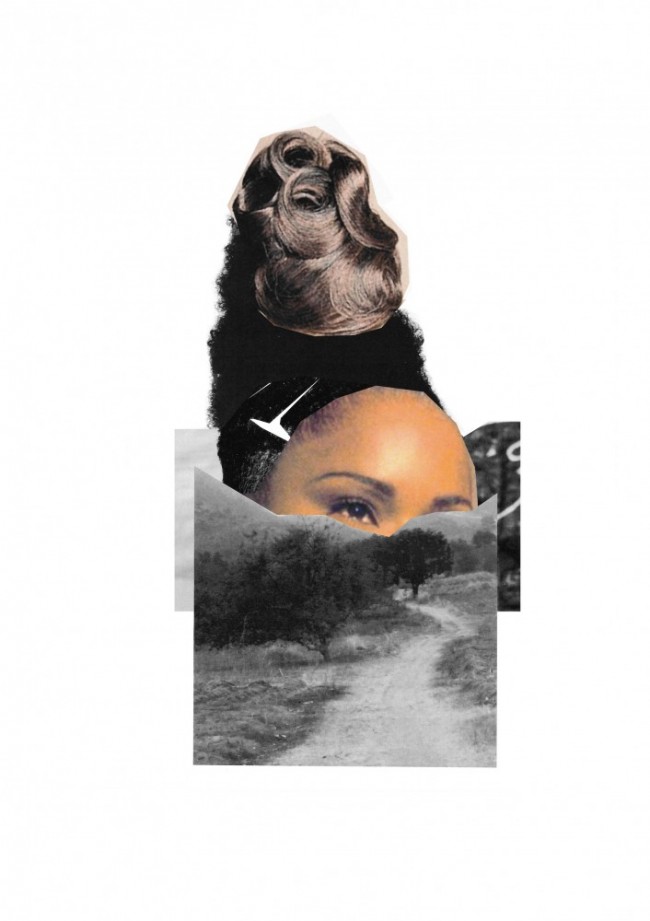

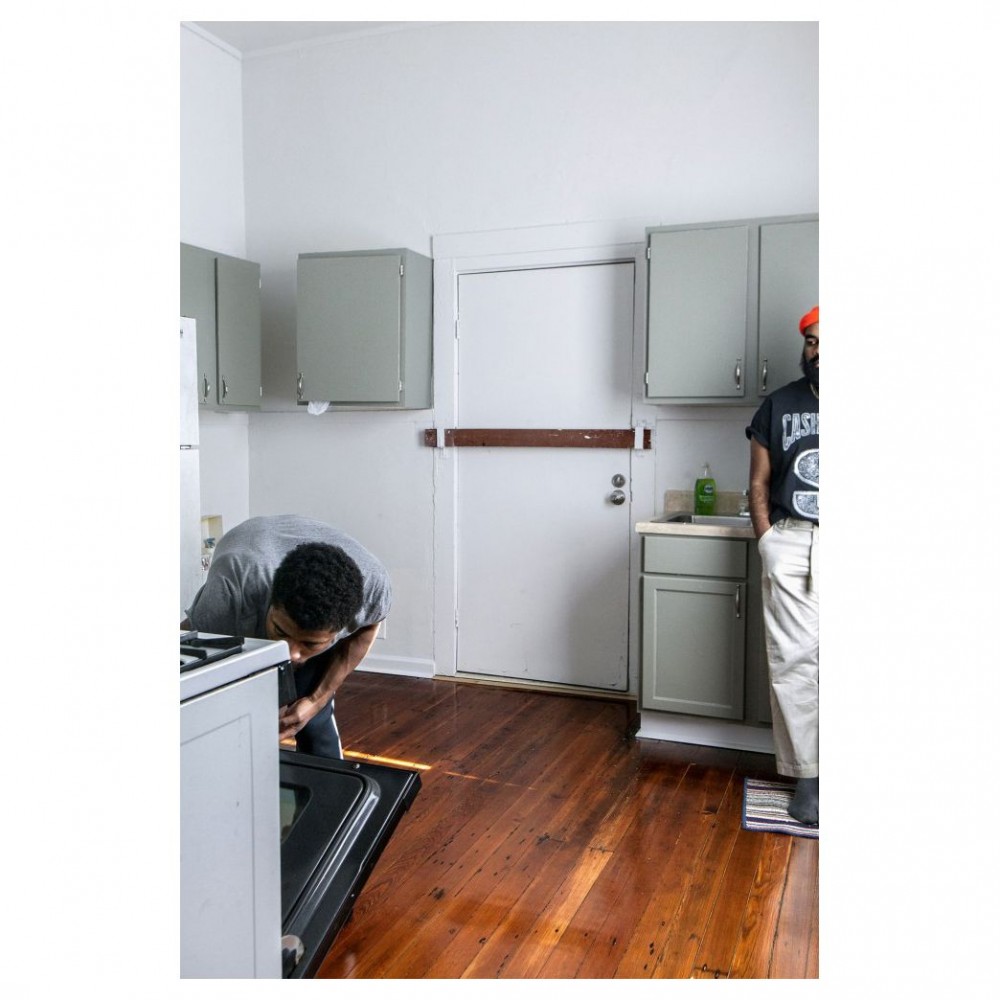

Left: Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Keep that one metaphorical, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York. Right: Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Sweeping the bricks to the edge of a door too heavy to hold its own., 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

I think a lot of people make work because they’re not seeing what they want to see out in the world. Do you think your work is in response to what you’re not seeing or are you trying to be a part of a larger conversation?

When I started working, I was thinking about myself, I was thinking about the ways that I didn’t see portraiture portrayed. As I’ve worked more in this vein, it’s become clearer to me how other people have worked in this way both explicitly and not. For instance, Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes made The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), and those were images that I believe Roy had taken just on to himself of people in a very documentary capacity. But then Langston Hughes's job and really Roy’s job as well, in terms of the sequencing of the photos in the books, was to recontextualize the reality of those images in a fiction around this larger theory around this community of black people. I make work in that legacy of making images of something that’s in reality. It’s making images in this improvised way but trying to re-contextualize it so that it serves some other truth or reality that’s not related to biography or related to fact.

I’m interested in how, going into the future, people will document black space and what they’ll choose to emphasize. If I think of the 70s, black space was Good Times and The Jeffersons, at least in media and in the public imagination. In the 80s was The Cosby Show. The 90s, I think of Living Single, that house that they all lived in.

That is something that I’ve considered about my photographs before, that they are a representation of what folks’ living spaces look like now, especially in New York. There are several images in which the paint is really indicative, the buildup of the oil paint to me is indicative of New York and that the hand of New York is constantly changing over and over again. People don’t live in the same apartment for more than two years. Maybe they’re not even on the lease, period. They’re images of people’s temporal relationship with New York, the transplants who have come here from any number of places who are just trying to take root here.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Inherent distance, 2018. (Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.)

You named the 2019 exhibition that you did at Baxter Street Camera Club of New York after Billy Preston’s "I Wrote a Simple Song.” This is a general question, but I’m a music person so I have to ask: What role does music play for you as an artist? When I look at your work, I feel music in it. There’s a musicality to the images that you create.

I definitely wish to create in a way that I find that music does. Music is really instantaneous in its communication, and it also is a really animated communication. Whereas, I think photographs are really delayed, and visual art can be a really delayed experience. I think about music and the tenets of it and how to adopt them into making visual work. I don’t know why, but my body already had an answer to this question, but it’s not giving me the words. (Long pause.) Someone asked me to make a playlist at the beginning of the month that I’ve been working on for the last two months. The playlist is about a trajectory of a relationship and therefore a trajectory of love and its dissipation. That playlist has been on my mind a lot. I use the same brain to make the playlist as I do the images. For some reason, I keep wanting to talk about Jill Scott, “Slowly Surely,” because that song is constantly on my mind because it is so simple. Simple format, but it is so impactful. I love how much of a wordsmith she is and how agile she is with language that she can just break apart a singular word and do something to it. Music definitely has an impact on how I think, what I do.

At Baxter Street, it was a kind of installation. It wasn’t just photographs framed. Is that the first time you did installation for the show?

In this part of my career, yes, but the very first show that I did was an installation, but I don’t ever show anybody those images.

What made you want to do an installation for that show?

In the same vein of the captions for the images, how the captions appear to have a very random relationship to the image, the installation of the image is yet another point. It’s an element to help guide the experience of the photograph. It makes sense to me to not just put something into a regular frame. That limits an opportunity for additional context. A part of that goes back to this obsession with space, this obsession with objects, this obsession with physical interiors and wanting to make an object out of photography, something that is tactile and tangible. That is a direct reflection of my upbringing going to all these different houses and it just sticking with me.

Is there an image or a scene or space from when you were younger that you go back to a lot?

My maternal grandparents’ house is more or less the same as it has been since I was young. The mirror wall that they had that leads up into the main part of the house has always really stayed with me. There was a particular smell that I remember my cousins’ house in Maryland having when we would go to visit. It was a really comforting smell. It definitely smelled like skin and it smelled warm and maybe even a little like mothballs, but it just stuck with me.

Interview by Tony Jackson Jr., a New York-based curator and a DJ and musician performing as Skype Williams.

All images courtesy of Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

To purchase the poster Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. created for MIEN, a Pride Month exhibition organized by TRNK and Tariq Dixon to benefit the Ali Forney Center, click here.

To purchase the special edition of PIN–UP 25 with Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.’s cover click here.