RECONSTRUCTIONS PORTRAIT: V. Mitch McEwen on the lost futures of reconstruction

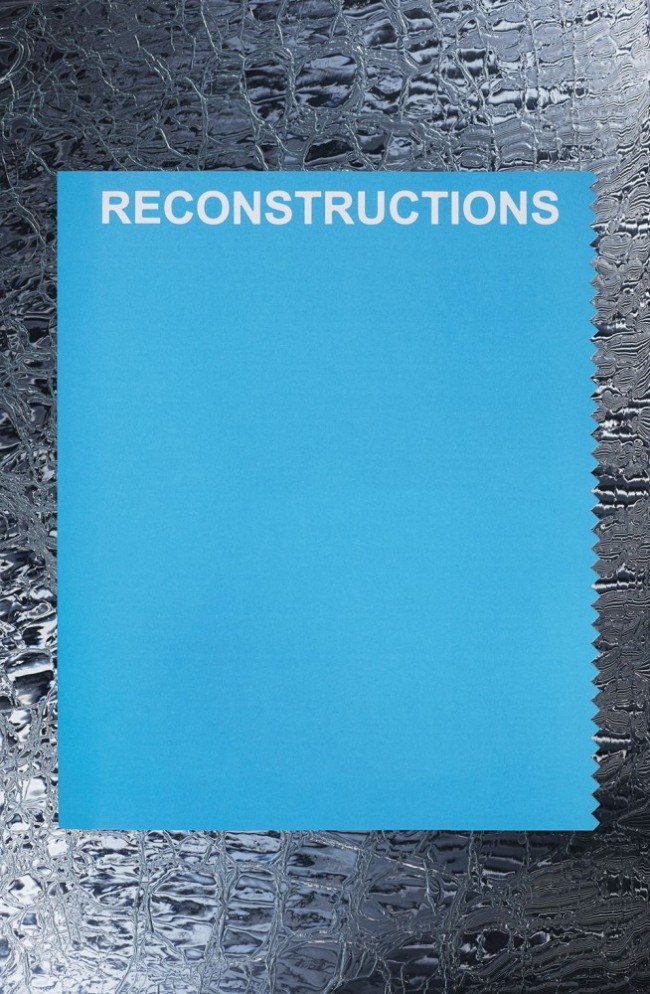

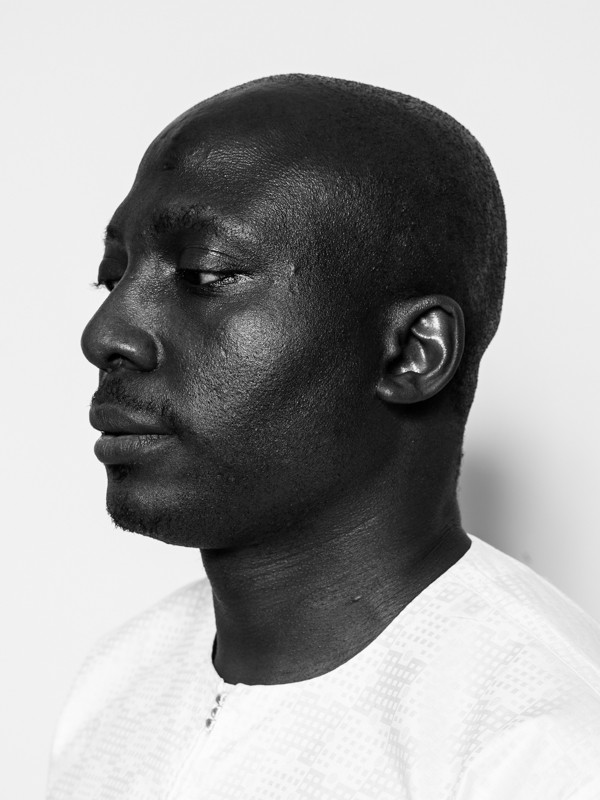

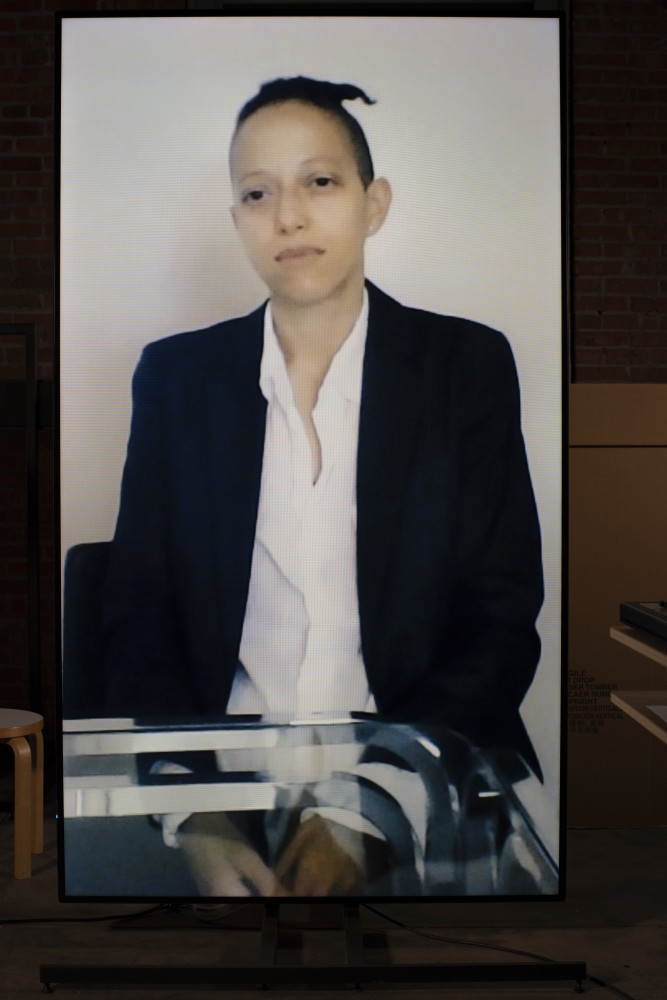

𝘖𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘰𝘤𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘰𝘧 Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America 𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘔𝘶𝘴𝘦𝘶𝘮 𝘰𝘧 𝘔𝘰𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘈𝘳𝘵, 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘥 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵 𝘋𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘳𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘰 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘸’𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘢𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘵𝘦𝘤𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘴, 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘥𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘨𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴. 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘯 𝘱𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘢𝘤𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘪𝘦𝘸𝘴 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘪𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘵 (𝘴𝘦𝘦 𝘣𝘦𝘭𝘰𝘸). 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗’𝘴 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘚𝘱𝘦𝘤𝘪𝘢𝘭 𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘭𝘴𝘰 𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘪𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘦. 𝘈 𝘗𝘐𝘕–𝘜𝘗 𝘱𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘩𝘪𝘱 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘮 𝘉𝘳𝘰𝘸𝘯𝘦.

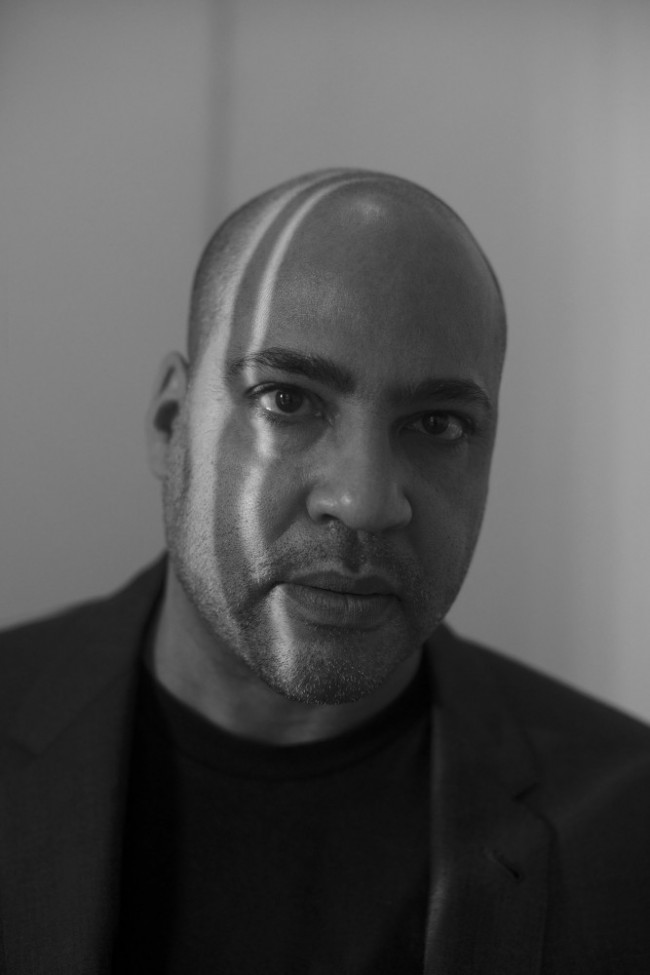

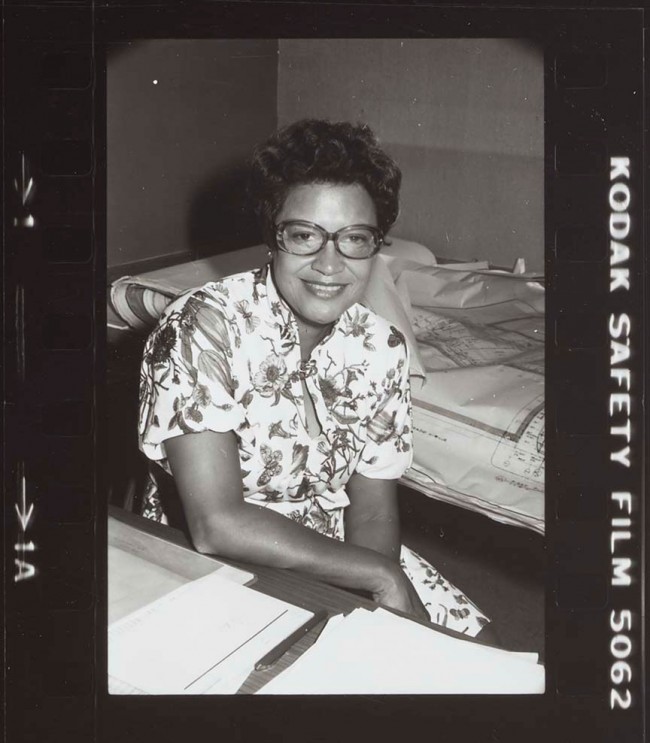

V. Mitch McEwen is Assistant Professor at Princeton University School of Architecture, director of the university’s architecture and technology research group Black Box, and co-founder of the New York design practice Atelier Office. Working at the intersections and boundaries of computation, urban planning, and experimental practice, McEwen uses architecture and technology to ask what it means to make life in the city today. She is a co-founder of the Black Reconstruction Collective.

Mitch McEwen photographed by David Hartt for PIN–UP.

What led you to architecture?

I grew up in Washington, D.C. in the 1980s and 1990s in the center of the district, near the Potomac River. When I walked to the National Mall or the major metro stations — especially before the city finally added a line to serve the Black neighborhoods and Howard University, which didn’t happen until I was in junior high school —, I would walk past Marcel Breuer’s building for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It makes the scale of the federal government tangible, as do the national museums on the Mall. This is a massive and ridiculously wealthy country. It wasn’t until I left D.C. that I missed this in-your-face civic architecture. Much of this country presents itself as fake little villages and towns, even parts of Queens or San Francisco or Detroit. Anyway, I also grew up loving math and drawing — even drawing on the computer with an early software called Logo in the 1980s. In college I vacillated between majoring in French Literature and in Social Studies and Economics. I graduated from Harvard with the degree in Social Studies and Economics, but all my electives were in literary theory, cultural studies, or visual arts. I vaguely thought of architecture as a field that could treat space as a kind of currency, escaping the terms of economic development and wealth distribution. I took two painting classes in the Carpenter Center — that was when I first heard of Le Corbusier. After college I worked in finance for a few years in Silicon Valley and San Francisco. It was enough of an experience to confirm that my activist bent as an undergrad was neither unfounded nor naïve. Indeed, what I saw of advanced capital accumulation at the turn of the millennium was even more destructive, violent, and patriarchal than I had expected. I applied to architecture grad programs not really expecting to be accepted, but wanting to find a path as far from finance as possible. In some ways I was led to architecture because, at the time, it seemed irrelevant. I wanted to do something irrelevant. Unfortunately, I eventually figured out that the “irrelevance” of architecture is highly calculated and part of how it maintains its relationship to the status quo and capital. Now I am concerned with attacking and dismantling that “irrelevance.”

How has your practice evolved?

When I think about it, my practice has blossomed in times of economic crisis. The 2008–09 subprime mortgage fiasco was the context in which I launched the initial form of my practice, an experimental space in Brooklyn called SUPERFRONT. I curated other architects and artists and collaborated with choreographers and performance artists and did an experimental loft-size version of a lot of the kinds of collaborations I am doing now when I partner with museums or through the lab I run at Princeton. In this current time of economic contraction and pandemic, my design partner Amina Blacksher and I have merged studios to form Atelier Office. We are a New York design firm, focused on working with clients who are new to architecture or actively expanding beyond their comfort zones. In the decade prior, my former studio designed a number of aggressively scrappy projects, including a vacant house in Detroit that became House Opera and a film gallery in Brooklyn. I lived in Detroit for four years and did a number of light-touch urban design projects there, including the Jefferson Chalmers masterplan on the East Side of Detroit. My work consistently cuts through high/low classifications. When I teamed up with WORKac as a finalist for the Women’s Building project in New York City, the primary focus of my design contribution was an old swimming pool and new urinals. For me it’s been important to take a vacant house in Detroit as seriously as the Venice Biennale.

What does “reconstructions” mean to you? Both as the title of the show and as a historical or contemporary reference?

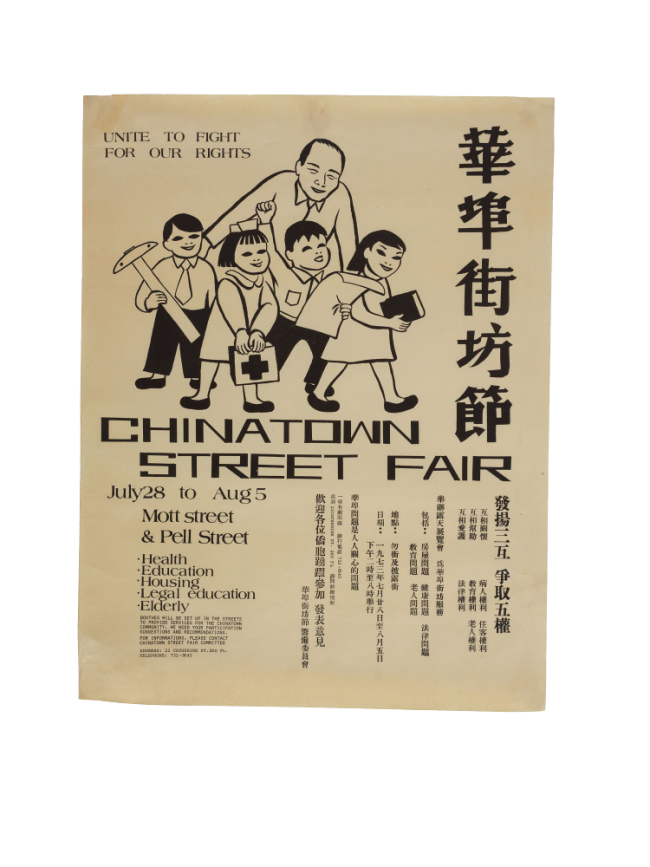

Imagine if the Enlightenment had lasted only eight or ten years. Imagine if Descartes had been assassinated after he published La Géométrie and never got to write Méditations métaphysiques. Would the French Revolution have even happened 150 years later? Would the U.S. have even pretended to be a democracy? To me this is the scale of questions opened up by Reconstruction. It was a moment for crafting a Black citizenship in this country and starting to untangle all the structures that conflicted with the potential of Black citizenship. Land was transferred. Black people voted and elected Black senators in the south. There would be no Mitch McConnell if Reconstruction hadn’t been halted by assassination and domestic terrorism. How cities developed and how the public apportioned political power would be radically different. We are still living in a version of this country where the inheritors of the ideology and wealth of plantation slavers are afforded subsidized political power. I understand the title of the exhibition as an invitation to produce radically speculative work that engages these questions architecturally. The stifling of Reconstruction did not only harm and limit Black people. By limiting the potential of Black radical thought — not the thought itself, but the potential of the thought to be realized or to do certain disciplinary work, or to be circulated — the century-plus delay of Reconstruction has robbed this country of so much of its potential, has delayed architectural invention, and has pitted this nation against its cities.

Can you describe the project you are creating in response to the MoMA Reconstructions brief? Where is it and why did you choose that location?

My project for MoMA is sited in New Orleans — not New Orleans as we know it, but another version of that city imagined by New Orleans artist Kristina Kay Robinson. Robinson’s version of the city, called Republica, asks what New Orleans history would have been if the 1811 German Coast uprising against enslavers had been successful. Staging the project there allows me to speculate on architecture for a free Black America. This opens up questions of materials and industry, form and computation, maintenance and labor. The driving question has been: “What architecture would Black people have already invented if we had been truly free for the last 210 years?”

Interview by Drew Zeiba

Video portrait by David Hartt

Editing by Jessica Lin

Music by King Britt presents Moksha Black

A PIN–UP production in partnership with Thom Browne

This video is part of a series of ten portraits David Hartt created for PIN–UP on the occasion of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America at the Museum of Art (Feb 20–May 31, 2021), curated by Mabel O. Wilson and Sean Anderson. The portraits were also published in the print edition of PIN–UP 29.