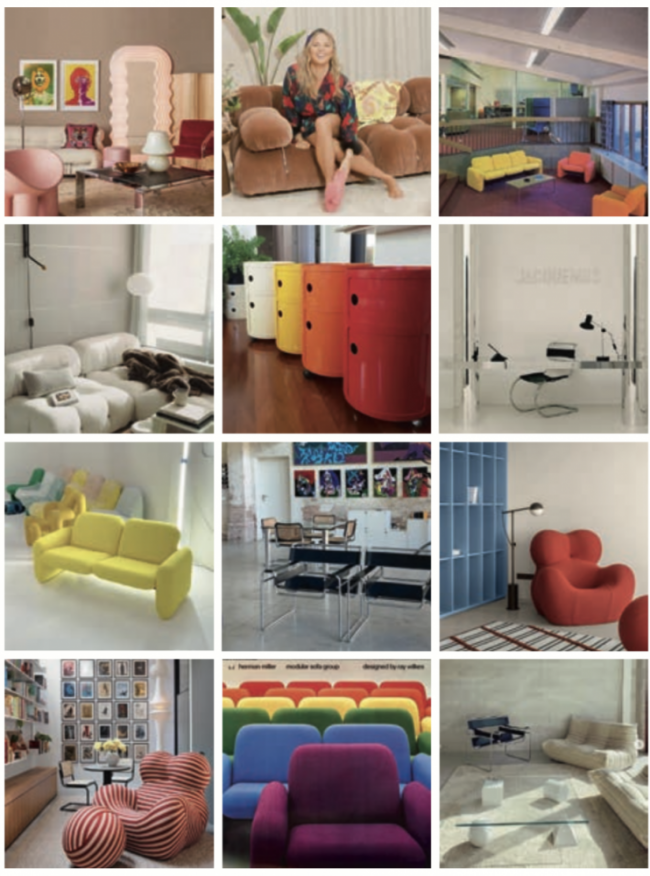

INTERVIEW: Jerald “Coop” Cooper, Founder of Hood Midcentury Modern

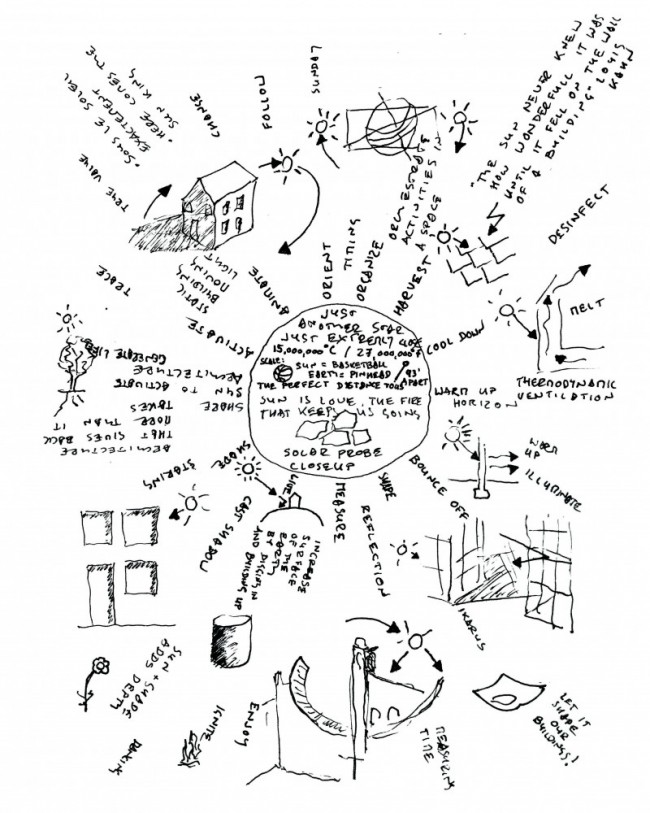

A hamburger restaurant in Cleveland, a carwash in Compton, a dance school in Connecticut, a gas station in Michigan — these are just a few examples of the overlooked retro buildings spotlighted by @hoodmidcenturymodern, Jerald “Coop” Cooper’s Instagram devoted to making connections between Modern architecture and Black culture. Cooper highlights the unique designs of mid-century buildings in Black neighborhoods across America, whether iconic structures like Compton City Hall designed in the mid-1970s by African-American architect Harold Williams, or structures that define the everyday built environment like Googie-style grocery stores or mid-century housing projects. He also probes pop culture and classic hip hop imagery from an architectural point-of-view with the intention of introducing a new audience to architecture discourse and in doing so generating a new way of connecting his followers to their built environment. The Instagram is just a start. Cooper has big plans for growing the Hood Century brand, including launching a historic preservation society, an editorial platform, and a line of educational flashcards. PIN–UP talked to the design enthusiast about what influenced the account, gentrification, and how getting turned onto architecture can be like micro-dosing shrooms.

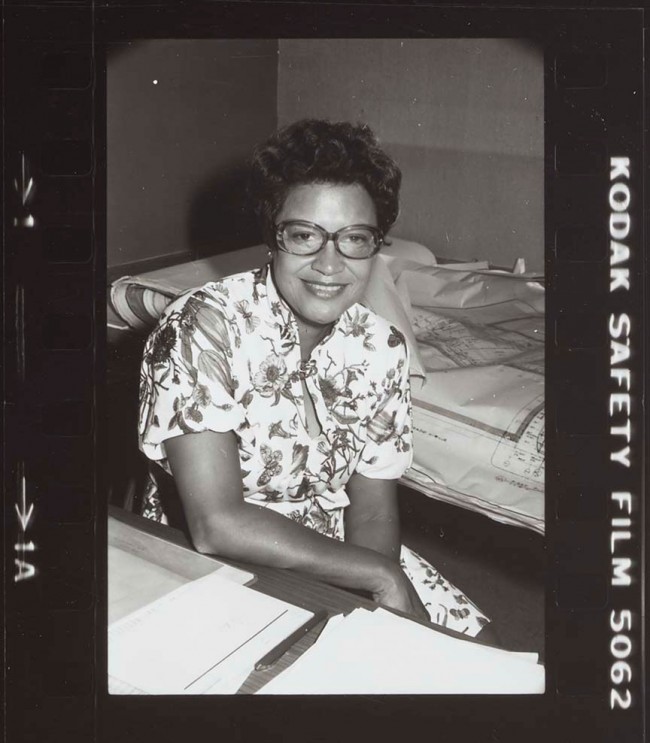

"Googie" building in Flint, Michigan. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

What’s your background, and where did the Instagram project come from?

I’m from Cincinnati, Ohio. I’ve been living in New York, LA, and most recently London for a little over a decade. I’ve been doing creative direction and managing music artists — Young Guru who is Jay-Z’s audio engineer and Ama Lou, an up-and-coming artist signed to Interscope. I had just finished executive producing Ama Lou’s last EP, and when I got done with it, I really felt like I should be doing something more creative. I’ve had this really lifelong interest in design. I collect art. But I hadn’t fully stepped into doing my own project. I was walking down the street I grew up on in Cincinnati. I saw these mid-century modern homes that I had been looking at all my life. At some point, I’d been able to identify them as mid-century modern. I had started looking at them differently. Man, living in Southern California, you see a lot of beautiful ass mid-century modern, like in Palm Springs and the Hills. I know for a fact though that the hood has no idea what these buildings are, for the most part, and their significance. And it sort of reminded me of the gentrification conversation. You can hate on people who come into the neighborhood, but they see the value of design that’s in disarray. There’s this disconnect between people from hood and knowing this architecture, and that disconnection is systematic. Housing disparities make it where Black and brown people don’t identify with these homes really being theirs, you know. And so I was like, oh, I got the solution: let me introduce the community to mid-century modern, which is like this huge Americana thing similar to how hip hop is this huge “urban” Americana thing. I thought, let me put them together.

Mid-century multi-unit housing in Los Angeles, California. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

And it’s interesting, like with cycles of gentrification. Older housing stock like a hundred-year-old brownstone in Bed Stuy has been identified as valuable for some time now and gentrification in neighborhoods with these buildings is long underway. But with mid-century modern architecture, it’s much more recently been considered historic to a wide audience. Like in Columbus, Indiana, it’s only in recent decades that they’re creating institutions around the historic preservation of their iconic mid-century architecture.

Hood Midcentury Modern, we’re going to launch a historical preservation society.That’s like the big thing. Our culture, hip hop culture, we can’t expect other people to do our work. Some random preservation society isn’t going to look at Marcy Projects the same way we will, knowing that Jay-Z is one of hip hop’s first billionaires. That site just doesn’t matter for them, but it matters for us. Or DMX’s group home in Yonkers where he had this creative helm. I remember there was this discussion on James Baldwin’s home in France, and they didn’t preserve it in the end. Preserving these sites has an effect on the impact these artists have on a younger wave.

The Horgan Academy of Irish Dance in Connecticut. Initially built as a bank in 1964 by architecture firm Alexander and Nichols. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

And with getting people involved with preservation, is there a goal of having people more in control of and investing in the neighborhoods they grew up in?

There you go. 100 percent. It’s like there’s this veil over things like a preservation society and civic duty. It’s not as bureaucratic as some would make it. But people feel like it’s not for them. So we’re gonna take the veil off so that people know they can get involved civically. They can get to know urban planners — even just know that urban planners exist.

The Florida Tropical Beach House on Beverly Shores, Indiana. Originally built for the Homes of Tomorrow Exhibition in the 1933 Chicago World's Fair. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

We have a family-owned building in the West End of Cincinnati. The West End is where my family migrated during the Great Migration from the South and was one of the last stops on the Underground Railroad. My family stayed there. Pops grew up in Laurel Homes, one of the United States’ first integrated housing projects. This is where Bootsy Collins is from. James Brown launched his career in this hood when he signed his first deal with King Records. In the 20s and 30s half of the city’s African Americans lived in the West End. I swear it’s like less than 10 miles from Kentucky, the South. No lie. This neighborhood is being gentrified right now. There’s a 100-plus-year-old church I grew up going to which is now being demolished for a new MLS soccer stadium. If I would’ve been on this before, I could’ve done something, but I wasn’t. I was on this music shit.

Protesters during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement gathered around the 1976 Compton City Hall by architect Harold Williams. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

What’s your definition of mid-century modern?

When I think of mid-century Modern, I think of Palm Springs. I think of walking into a crib and seeing the pool because the guts of the crib doesn’t have a lot of walls, just windows, and it really supports the idea of indoor/outdoor living. My favorite type of a crib is a house that’s centered around a pool, garden, or an outdoor space. If you look at mid-century modern, I think there’s a real deep connection to wellness and mindfulness. Man! Those “Folded Plate” roofs (the ones that look like zig zags) are generally my fav! But then, you know, we always like to show various Modern styles like Art Deco, New Formalism and International Style.

Sweet Retreat ice cream shop in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

Even if I accidentally post the wrong type of building. It’s a concept. We’re working through it, and what I’m noticing is that a lot of people are learning with me. That’s the really cool thing. People are hitting me up like, “yo this house, this was in my neighborhood. I always liked it, but I didn’t know all this.” The more you learn about this stuff, you start to see the hood differently, shit, the world. I feel like everything opens up, and so you drive through these neighborhoods, and you start to see these narratives. How different cultures had different styles, you know? It really feels like a great microdose of shrooms (laughs). It’s just like, “Oh shit, I can see it now.” And I know that’s happening to my friends and the people who are following, and that shit is exciting.

"Googie" car wash in Compton, California featuring a Compton Cowboy. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

One of my favorite pictures you’ve posted is of this car wash and this guy on a horse.

That’s a Googie car wash. All that astro sort of Jetson-looking mid-century Modernism in Southern California is Googie, and Compton and south LA is a hotbed for it. And in Compton there’s this whole movement called the Compton Cowboys. They have been out a lot during the protests. It’s wild because a lot of people in Compton through the Great Migration came from the South or Ohio (laughs). So kids literally ride around Compton on these horses.

Was that where they shot the “Old Town Road” music video?

Yeah, I am pretty sure that’s Compton, and the director, Calmatic, was one of the first people to follow the account. What up, Chuck, hit my line fool, let’s make some art, haha. He’s a great guy!

In Karate Kid (1984), Daniel and his mother move from New Jersey to the South Seas Complex in Reseda, California. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

A big part of your project is showing this architecture in popular media.

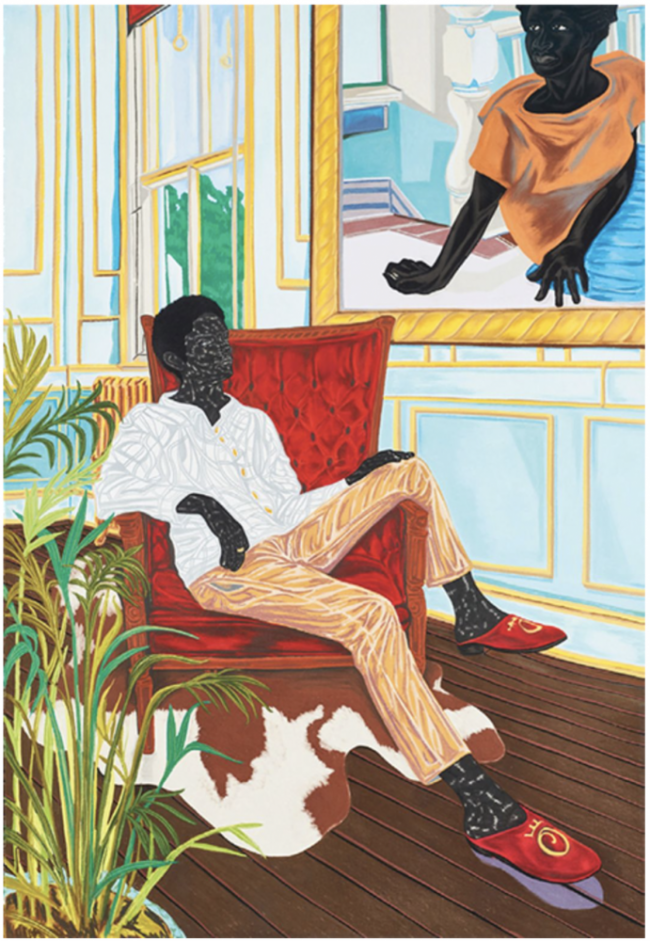

I thought that that would be a dope connector, you know, for people to have those “aha!” moments. If you watch the Martin show, which was and still is one of the best Black comedies, they always pan in on his apartment in the intro and coming back from commercial breaks. Like in 2006 or 2007, I saw the building in Detroit, and I literally lost my mind. I was like, “Oh shit! That’s the Martin building!” My boy looked at me like, “What the fuck, how do you know that?” (Laughs.) I’m like, “Dude I pay attention.” I’m really obsessed with figuring out how to connect this foreign thing to people for them to see that it’s all around them. And media is a great way to do that whether it’s images of Biggie or MLK with mid-century modern architecture. I’m gonna do a post about Karate Kid. In the movie, when they move out of NJ to Cali, his apartment complex is mid-century. Training Day has the Imperial Courts projects in it. On Issa Rae’s Insecure, her characters’ apartments are all mid-century modern. What I’m doing with this account it’s not necessarily about the hood. It’s about the hood scene, the hood aesthetic, and drawing that connection.

Cirque Daiquiri Bar and Grill in Atlanta, Georgia by architect Henri Jova. Interiors by Eero Sarinen for Knoll, Herman Miller, and Virginia Bowen. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

The hood seeing themselves in this discourse.

Exactly. And listen, seeing me, an African American man that’s 6’2”, taking pictures of buildings, of homes in the hood, I cannot tell you how fucking weird that is for people. (Laughs.) People are like, “What the fuck are you doing here? You look like you’re up to something, ” but that has opened up so many intriguing conversations. I find people who know about this shit. An African American male and female who’ll come up to me and start speaking to me about this shared history of a building. Or a lot of times when people have been like, “Bro, what are you doing taking pictures, you know that’s what police do.” And since I’m from the streets, we can sit down and have a discourse. Then at the end, they'll be like, “You’re a weird motherfucker.”

Mid-century Modern building in Macon, Georgia. Courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.

Interview by Whitney Mallett.

All images courtesy @hoodmidcenturymodern.