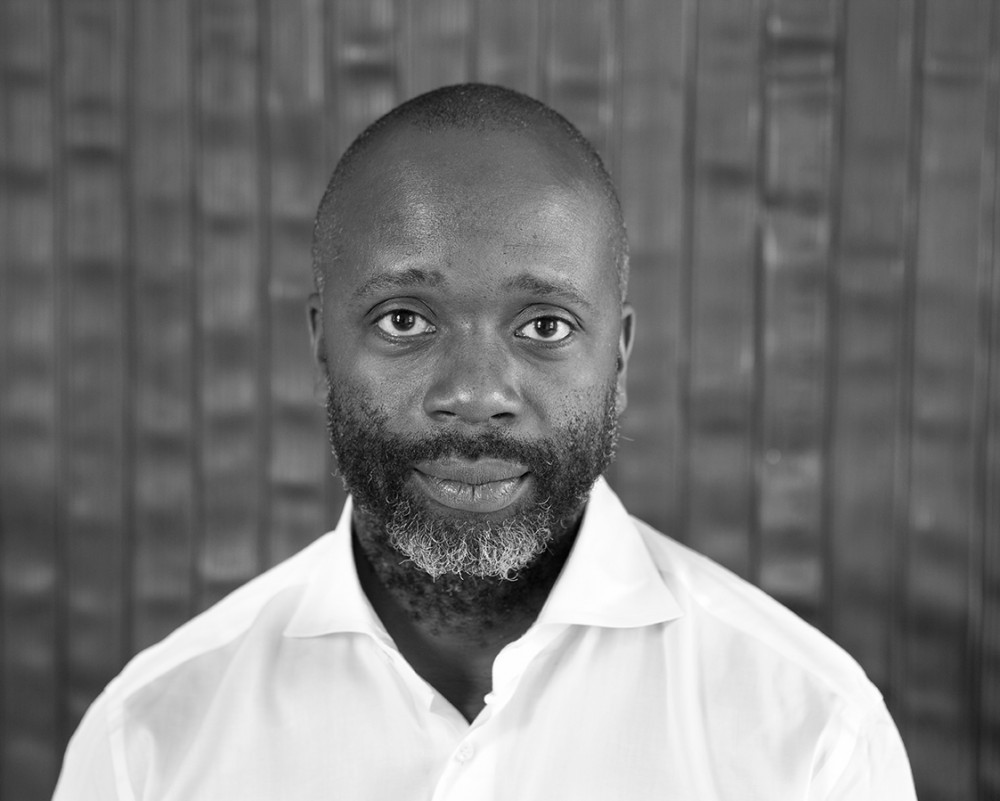

Artist Theaster Gates On Beetle-Damaged Ash Trees and Urban Catastrophe

Theaster Gates has a sprawling practice that includes both object making and urban interventions knit together by ideas of reclamation and transformation. This week Amalgam, the artist’s first solo exhibition in France opens at Palais de Tokyo, including sculptural works that repurpose the wood from ash trees eaten away by an invasive species of beetle wreaking havoc on Chicago’s arboraceous parks. The same salvaged wood is featured in an architectural project led by Farr Associates, a new home for the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, which opened January 7, 2019. (Gates is a visual arts professor at UChicago as well as an advisor at the school.) It was Gates’s idea to repurpose the damaged ash trees in the Harris School’s Keller Center project, the reused wood becoming an integral part of the renovation made to the mid-20th century building designed by Edward Durell Stone. Gates also owns the South Side facility where the wood was milled.

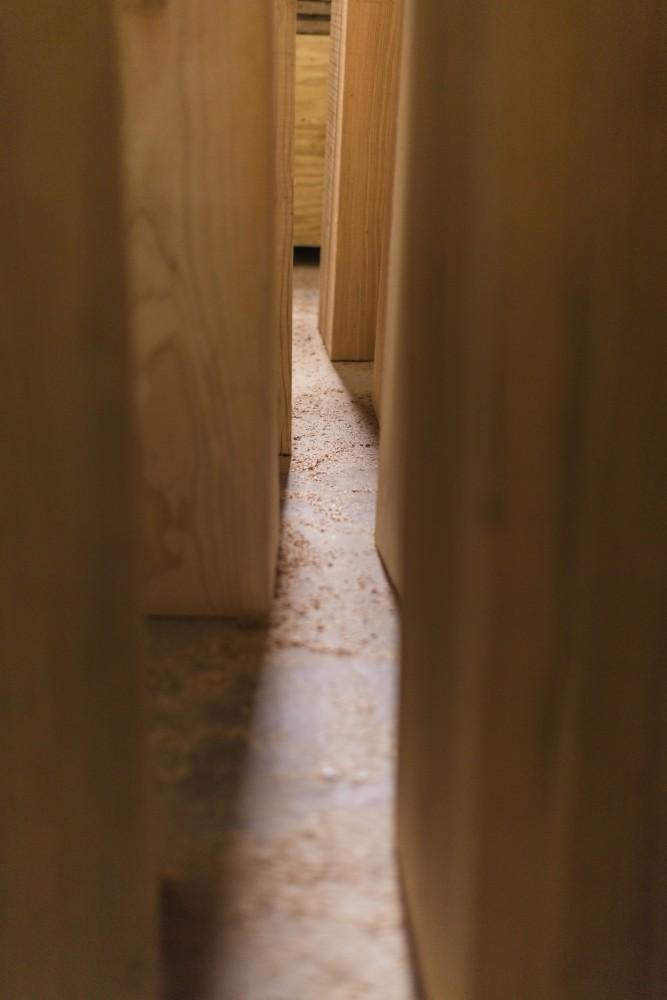

The Keller Center featuring repurposed wood from beetle-damaged ash trees. Photo by Jacob Hand, courtesy of the University of Chicago Harris.

Starting first as a potter, Gates expanded his practice to include urban redevelopment in his hometown of Chicago working on the scale of buildings and neighborhoods. He studied both ceramics and urban planning, as well as religion. Over the past decade since Gates started the Rebuild Foundation — its mission is artist-led community revitalization, rebuilding the cultural foundations of underinvested neighborhoods — the non-profit has transformed more than 30 vacant buildings into cultural community spaces. At the same time, Gates’s art objects like firehose readymades and sculptures comprising bound editions of Jet magazine also employ salvage and recontextualization. PIN–UP talked to the Gates about the symbolism of repurposing these ash trees, working at multiples scales simultaneously, and responses to urban catastrophes.

How did you get involved in this Keller Center project?

The city had given me a call that there was this challenge with these infested trees. Their desire was to find some solutions but also have artists engage with the trees. When I realized there were so many trees — eventually 90,000 trees would have to be cut — I thought the most appropriate move, art or not, would be to build a mill so that the trees could be kind of smartly managed instead of being turned into mulch. So I started a mill three years ago with some support from the Ford Foundation. The mill was up and running, and about a year into the facility being up, I became a part of the faculty of the Harris School, which was in the process of getting a renovation. The Harris School was interested in the mill and in having some, you know, policy-cum-practice or some kind of interaction that could be a clear articulation of the action of policy. In this case, what would it mean for the city of Chicago to partner with a creative in order to create a kind of a work-training opportunity via one of the challenges of the city? We then created an opportunity for the wood to be available for the Keller Center.

Can you talk a little bit about the mill? Who is it giving jobs to?

The mill is an extension of my studio. In some ways its goal wasn’t necessarily to amplify job opportunities. The problem was the problem of dead trees: how do we solve it? I thought I would identify a miller and my lead miller’s name is Damon Doerschuk. I thought Damon — he’s been doing this a long time — would need support and we would identify support in the neighborhood that could help him make good on these three or four thousand trees that we’ve been given by the city. I think that more than job creation it was tackling really big problems with big ideas and local workers. It almost feels more like poetry than workforce training.

-

Wood from the beetle-damaged ash trees being milled in a South Side facility owned by Theaster Gates. Photo by David Sampson.

-

Wood from the beetle-damaged ash trees being milled in a South Side facility owned by Theaster Gates. Photo by David Sampson.

And it’s very poetic — there’s some symbolism with these dead ash trees being given new life, very Phoenix rising.

There’s definitely a little bit of Phoenix. The metaphor that I like kind of complimentary to that — there are these situations when there’s a resource, whether it’s people, raw material, or the past, and there’s a tendency to turn it into mulch or to forget it or to throw it away. So I think the poetry for me is also our ability to process through creativity or to process through art some of what seem like big challenges of the city in order to make great things, like the Keller Center, happen.

You mentioned this project is about putting policy into practice, so what are the goals or the mission of the Keller Center that they’re aspiring to incubate in that space?

The school itself is really interested in the relationship between policy and people. For me personally, I’m trained and I believe in the arts, and I’m also super interested in cultural policy and systems. If policy is the law, the regulation, and the systems that govern a set of activities then I’m interested in how those systems create opportunities or restrict opportunities for culture, creativity, and artists. I think that one of the things that’s happened as a result of me being aligned with the Harris School is that there’s a new trajectory of interest in the relationship of art, artists, and the impact that can happen in the built world and in the policy world.

You’ve been working on the scale of buildings for a while, but was it different working in a university context? I imagine there’s a lot more bureaucracy you rub up against.

I think I’ve always had to work at multiple scales and in multiple modes at the same time. There were always things that I could do alone that were better alone and there were things that I couldn’t do alone that I needed institutional alliance to do. What happens if you work alone and with an institution and with the city and with the art world? Would it be possible one project at a time to just nail ideas and just say this kind of idea could only happen by an individual artist and then say well this idea could only happen if the artist was working with a world class academic institution and so rather than being beholden to one mode of making, I just move between modes.

I imagine it takes a different kind of skill set to be able to navigate and move within those systems sometimes.

Yeah, I have 17 personalities. And the movement between modes it requires a certain kind of appetite and intelligence, but it also requires a certain amount of theatre and a discipline toward the theater of the city or the theater of the academic institution or the theater of the self. And that’s where my pleasure is that I get to move between various stages enacting the forms of myself.

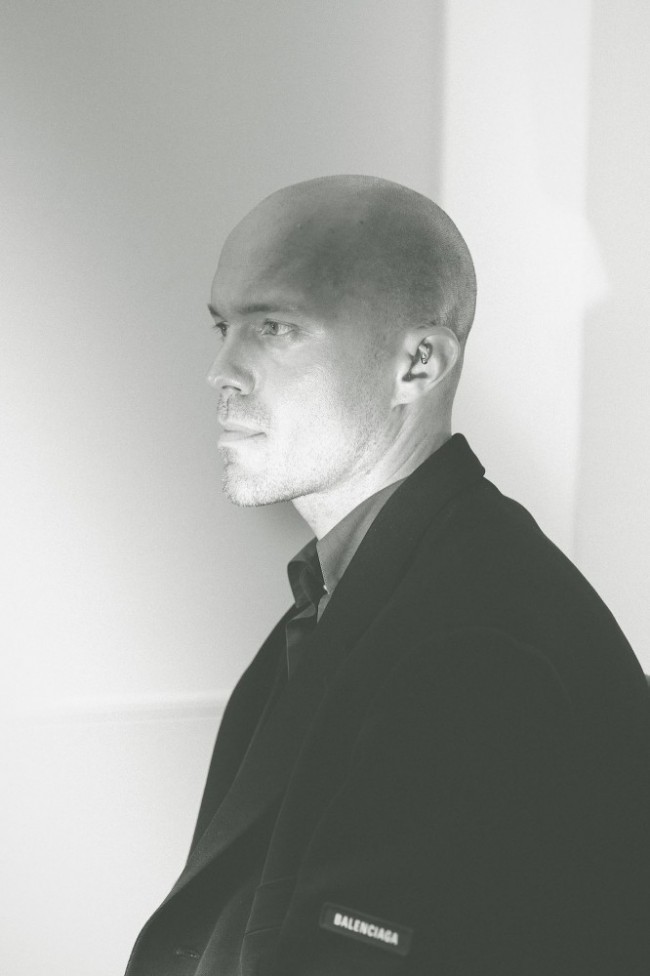

Preview images of Theaster Gates, Italic textAmalgamItalic text (2019) opening at Palais de Tokyo February 20. Photo by Chris Strong.

Have you made other things with the dead ash trees and used them in other projects?

We’ve built practical things in Chicago like tables and shelving and boxes for my ceramic wares and things like that. But currently I have an exhibition that is opening February 20 at Palais de Tokyo where the remaining trees that we milled have a kind of significant cameo in the exhibition as these kind of funerary poles, these pillars that reflect the history of traditional African religious rituals and in a way an honoring of black ancestry on this island called Malaga. They’re playing a kind of poetic role as well as a practical role in my practice.

You do a lot of things in your practice to which reclamation and transformation are central. But I imagine in every project, you learn something new or things have different resonances. Was something that was revealed to you when working on either the Keller Center project or the other exhibition project you just spoke about using the ash trees?

When I decided that I would build a mill, I knew nothing about milling. I’m not a miller. But I recognized that the problem of these failed trees was a problem that needed a response. And so I’m learning the most about my instinct to respond to what I would call not a natural catastrophe but an urban catastrophe. And I’m learning that my art practice almost needs urban catastrophe as part of the artistic reaction, so rather than looking to challenges far away from me, I’m always looking for the challenges that are right up under my nose, right in my city, right in my house, right on my block. And maybe the unexpected beauty or unexpected opportunity that my practice has depended upon is these local nuanced situations that I could then myself active, find myself challenged by, and respond to that in the best way I can.

Text by Whitney Mallett.

Portrait by Sara Pooley. Additional images by Jacob Hand, David Sampson, and Chris Strong.