Didactics and Diversity at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial

“There are so many different ways that everyday citizens make space,” asserts Yesomi Umolu, who curated this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial together with curator-educator Sepake Angiama and architect-urbanist Paulo Tavares. Titled ...and other such stories, the biennial, this year in its third edition, spotlights both the diversity within the discipline of architecture in the 21st century — from standard building to urban planning to research, publishing, and more experimental modes — as well as how architects aren’t the sole producers of space. The multi-venue exhibition, which opened in September and runs until January 2020, showcases the work of over 60 architects and designers as well as artists, organizers, and all manner of spatial practitioners. In the words of Tavares, “This is not a show about architecture, it is rather a show on architecture.”

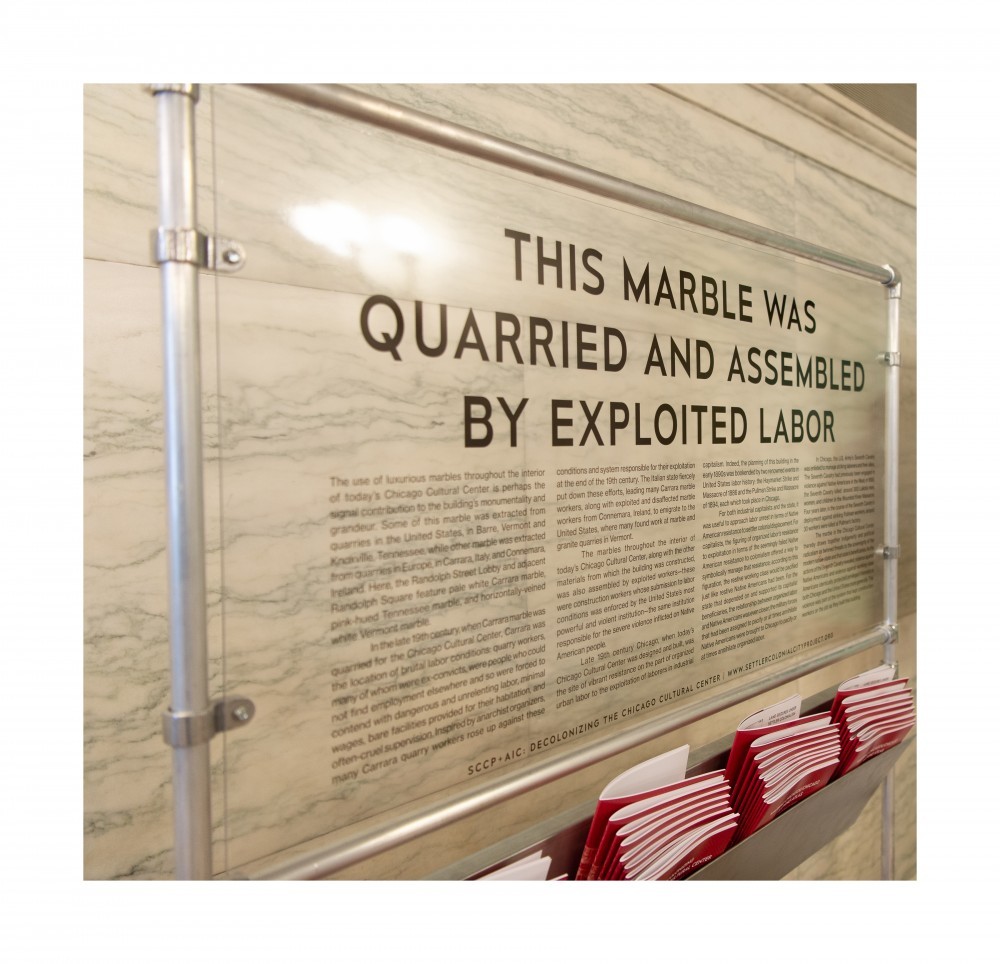

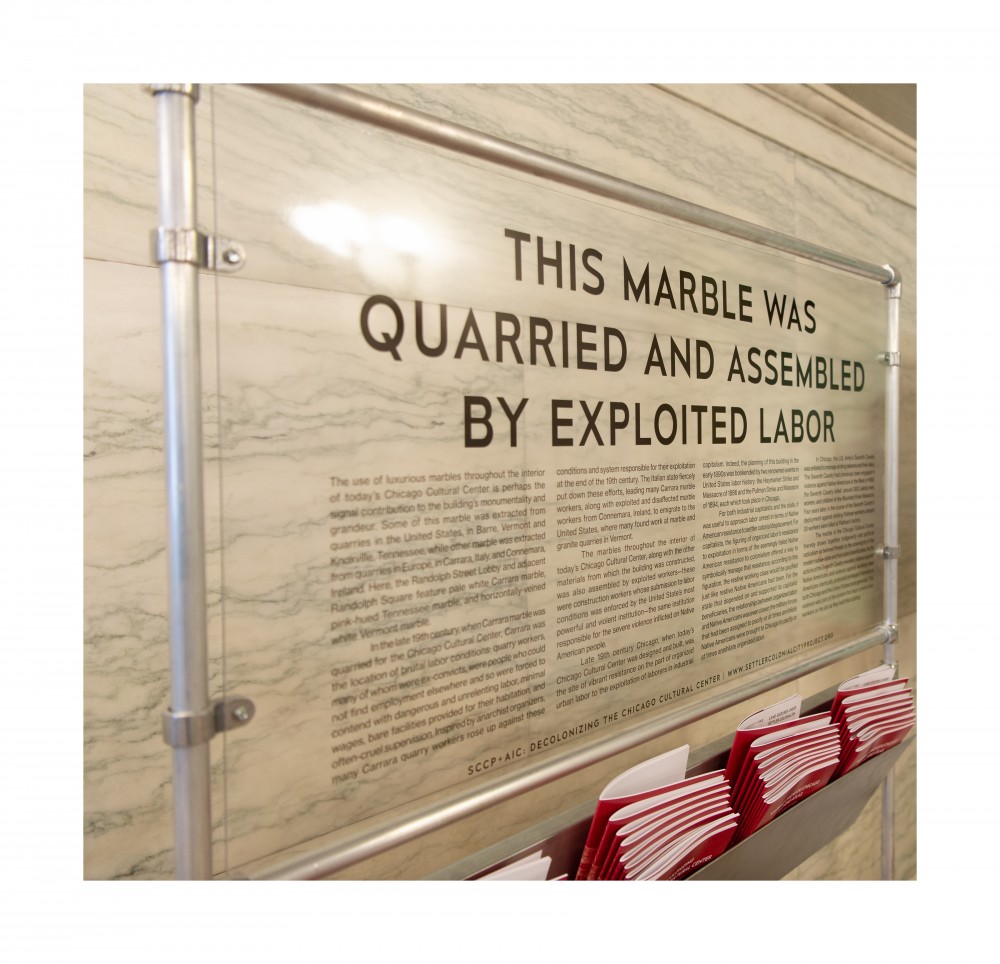

In addition to suggesting a focus on what’s often overlooked, Angiama explains that the title, ...and other such stories, reminds her of “fables, which generally have pedagogical dimensions.” One of the biennial’s most instructive narratives came in the form of an intervention at its main site, the Chicago Cultural Center, a late 19th-century structure resplendent in detailed tile work on stairwells and vaulted Tiffany glass ceilings. Throughout the building transparent panels featured bold headlines such as “Tiffany & Co. rendered settler colonialism ‘beautiful’’” and “This marble was quarried and assembled by exploited labor,” along with detailed texts and books to take away, forcing visitors to confront the ever-prescient architectural questions of who built our built world, on whose land, and with what resources. It was the work of the research collective Settler Colonial City Project as unobtrusive yet unavoidable didactics.

-

Settler Colonial City Project & American Indian Center,

Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Cory Dewald. -

Settler Colonial City Project & American Indian Center,

Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Cory Dewald. -

Settler Colonial City Project & American Indian Center,

Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Cory Dewald.

The 2019 biennial wasn’t limited to exhibitions at the Cultural Center. A Perkins+Will-designed school on Chicago’s South Side that closed in 2013 amid a mass shuttering of schools hosted numerous installations, some of which engaged local children directly. At the site of what was once one of the U.S.’s largest public housing projects, the lone remaining building is being converted into the National Public Housing Museum, the first museum of its kind, and was the site of an interactive sound installation by the Johannesburg-based collective Keleketla! The legendary Jane Addams Hull House hosted an interactive installation by Tania Bruguera and a quietly beautiful intervention by Jorge González made of woven dried cattail leaves. And the School of the Art Institute of Chicago hosted a project in Homan Square. There were also numerous other sites and partners participating in some form. “We wanted to understand Chicago not only as a backdrop to the biennial, but as a place that we could interrogate through our work, and through our research,” Umolu explains. “It was important that the biennial would not just happen in a downtown area, that we would seek collaborations and partnerships with different communities.”

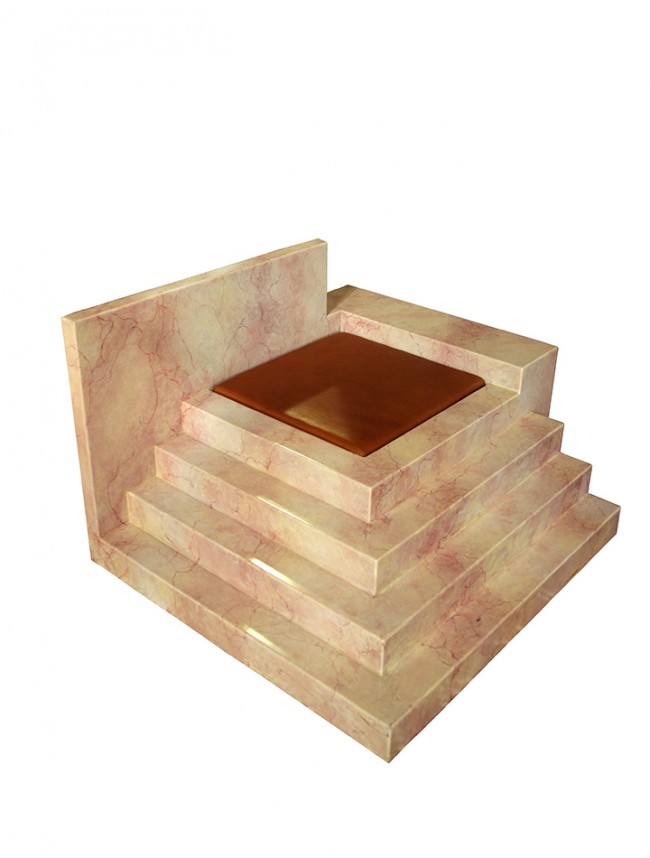

At the Cultural Center, Refugee Heritage by Decolonizing Architecture Art Residency (who were also featured in the inaugural 2015 biennial) was a particularly poignant installation. Wide concrete plinths of various heights, most relatively close to the ground, punctuated the room. Visitors could move through them, freely, so to speak, but also conditioned by their placement. On some of the platforms were photo books spread out — images of white tarps stretched over buildings, or foliage that contrasted against the artificiality of the cement platform. The project was intended to represent a fuller, more nuanced picture of refugeeness. The project referenced Dheisheh, a refugee camp built in the West Bank following Al Nakba, the disastrous event during which Israeli occupiers displaced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes; the would-be temporary encampment has become a town existing to this day. DAAR spent 2015–17 discussing nominating Dheisheh as a UNESCO World Heritage site, troubling normative, colonial expectations of what constitutes “significant” architectural heritage. Refugee Heritage served as a spatial instantiation of that application, inviting visitors to seriously consider the architecture that is so often given the least thought.

-

Left: Center for Spatial Research, Homophily: The Urban History of an Algorithm (2019); Foreground: DAAR, RefugeeHeritage (2015–18); Background: Sweet Water Foundation, Re-Rooting + Redux (2019). Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial and Kendall McCaugherty.

-

Sweet Water Foundation, Re-Rooting + Redux (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Kendall McCaugherty.

The Chicago-based artist Maria Gaspar also leveraged the power of aestheticized images of seemingly mundane architectural instruments of control in her piece, Unblinking Eyes, Watching. For the installation she turned a high-resolution image of the wall of Cook County Jail, the country’s largest single-site jail located in Gaspar’s childhood neighborhood in Chicago’s West Side, into a giant wallpaper. This wall serves as a boundary between a busy residential neighborhood and the closed off spaces of incarceration; by imaging, reproducing, and displacing this boundary, Gaspar forced a consideration of how incarceration defines everyday urban experience.

A project that proposed solutions to many systemic problems plaguing cities today was Re-Rooting+ Redux, which in the Cultural Center took the form of a pitch-roofed wood beam structure, inspired by the once-common Chicago worker’s cottages. The installation served as an outpost of the Sweet Water Foundation, an organization that has created a land trust and live-work-learn community on Chicago’s South Side. Re-Rooting+ Redux served as a gallery of sorts, which looked at the past, present, and possible future of housing justice and community land stewardship and featured displays such as a 1:1 photo of a collage of images of major figures such as Frederick B. Douglas and Ida B. Wills, a federal report on redlining, and photos from major events such as 1871’s Great Chicago Fire and the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, all linked by red thread. The piece was created by high school students during a Juneteenth workshop entitled “From ‘Blight’ to Light.” (The delicate, real-life version of the spread was to be found at the Graham Foundation.) Gaspar was hardly the only artist in the exhibition. Black Quantum Futurism (who we also interviewed) contributed an interactive Community Futures Lab for thinking through issues of time, place, and gentrification; Theaster Gates provided a multimedia room, with desks strewn with building materials and prints on the wall featuring texts such as “BLACK SPACE IS NOT VACANT” and “SPATIAL TRAUMA CRISIS CENTER”; and Do Ho Suh presented a ghostly projection.

-

MASS Design Group and Hank Willis Thomas, The Gun Violence Memorial Project (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Kendall McCaugherty.

-

Sweet Water Foundation, Re-Rooting + Redux (2019). Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial and Kendall McCaugherty.

Another art star, Hank Willis Thomas, perhaps best known for his figurative sculptures and public art commissions, collaborated with the Boston-based architectural nonprofit MASS Design Group for a particularly affecting architectonic installation on the Cultural Center’s first floor. Visitors were invited to walk through four interlocking, house-shaped glass structures. Low-slung, they felt tight and intimate even though their bricks were transparent. The project, created along with the nonprofits Purpose Over Pain and Everytown for Gun Safety, asked friends and family members of those who lost their lives to gun violence to contribute mementos throughout the biennial’s run. The objects — many quotidian: photos, toys, a Savers member card — were placed in the hollow glass bricks while recordings of individual testimonies played overhead. If you weren’t alone, you could see the hazy blur of others moving through the installation.

Forensic Architecture and Invisible Institute’s collaborative contribution also grappled with gun violence. Forensic Architecture is known for its incisive and systematic investigations of the spatial logic of violence — such as the audio research of Syria’s Saydnaya prison (PIN–UP 21) and the use of desertification by Israeli occupiers in Palestine (PIN–UP 26). While Forensic Architecture and Invisible Institute had produced a video showing their analysis of bodycam footage of the 2018 police murder of Harith Augustus, the team, in consultation with the curators, opted to not show it, as not to contribute to the spectacle-making of black death so common on Twitter feeds and cable news, “inflicting difficult images on visitors who had not consented to view them.” All visitors encountered was a room, walls painted black, with some text panels, two pairs of headphones, and a black curtain running one edge. Those who chose to see the video could look online or go to Peterman Studio in Chicago for the full installation.

-

Oscar Tauzon, Great Lakes Water School (2016). Courtesy the Chicago Architecture Biennial and Tom Harris.

-

Territorial Agency, Museum of Oil –The American Rooms (2019). Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial and Cory Dewald.

In thinking through the social impact of building, and simply living together, it is impossible to ignore the urgency of the climate crisis, particularly resource use and extraction. One room addressed these issues with particular success, and was among the most decidedly architectonic of the exhibition. Oscar Tuazon’s Water School was a plywood structure inspired by Steve Baer’s Zome House that Tuazon turned into a reading room on water rights. The Museum of Oil, Territorial Agency’s video installation, presented research on United States oil extraction, visualizing data from remote sensing and satellite imagery. Territorial Agency encourages oil to be kept in the ground, making it a thing of the past, thus framing the earth as a kind of museum stewarding it. (The irony of the biennial’s BP sponsorship is hard to miss, however.) There was also a sculpture by the artist-architect Joar Nango that referenced Sámi architectural traditions and a particularly informative installation by Somatic Collaborative which presented research that showed “how architecture and urbanism have shaped the spaces where resource extraction takes place” in South America.

As expansive as it is, ...and other such stories, like any exhibition, necessarily presents its own take on the state of spatial practice, a sort of architectural portrait. But with the proliferation of biennials and triennials, it is important to consider the even broader global conversations being presented by these exhibitions. “In recent years we have seen a phenomenon that one may call the ‘biennialization of architecture,’” Tavares said. “This begs the question of why this is happening and what are its effects to the field as well as to the real life of cities and citizens.” In the recently opened Lisbon Triennale, titled The Poetics of Reason, the curators state, somewhat cryptically, “architecture does rest on reason, and its aim is to shed light onto the specificity of this reason.” Enlightened “reason” in architecture has been the justification of much short-sighted top-down planning, however the Triennale curators counter this quick association with a sentiment that seems shared by the Chicago Architecture Biennial: “everybody is entitled to understand architecture without a specific background in the field.” The Sharjah Architecture Triennial, which opened in November, also shares thematic resonances with 2019’s exhibition in Chicago. It focuses on the “Rights of Future Generations,” primarily taking up as its concern the asymmetrical impacts of environmental catastrophe and how architecture produces and can prevent that in the name of human rights.

...and other such stories is a global exhibition, but what does this all mean for Chicago? “Chicago's urban fabric is incredibly complex and beguiling,” Umolu reflects. “But there is the question of how to make contemporary architecture and how to make space in the city today. How do you make it in a way that looks different or that might kind of have a different narrative from the grand histories that we're so familiar with?” Everyone shapes, appropriates, and reimagines the spaces we occupy. Why then, shouldn’t all those stories, be the stories of architecture?

Text by Drew Zeiba.

Images courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial.