2017: ANOTHER YEAR OF BIENNIAL FEVER

If cabin fever is “extreme irritability and restlessness from living in isolation or a confined indoor area for a prolonged time,” its opposite might well be “biennial fever” — extreme exhaustion brought on by the overwhelming number of architecture and design bi- and triennials that now take place in cities around the globe. It seems we’ve reached peak beard, but when will we reach peak biennial? Last year we had Venice, Oslo, and Lisbon, this year there was the second edition of Chicago as well as two new French biennials — Lyon and Orléans — in addition to Bordeaux and the Saint-Étienne design month. Keeping up with them all will soon be a full-time job… (If you want to measure the full scale of the phenomenon, or just stay up to date, our friends at Archdaily have put together a comprehensive list.)

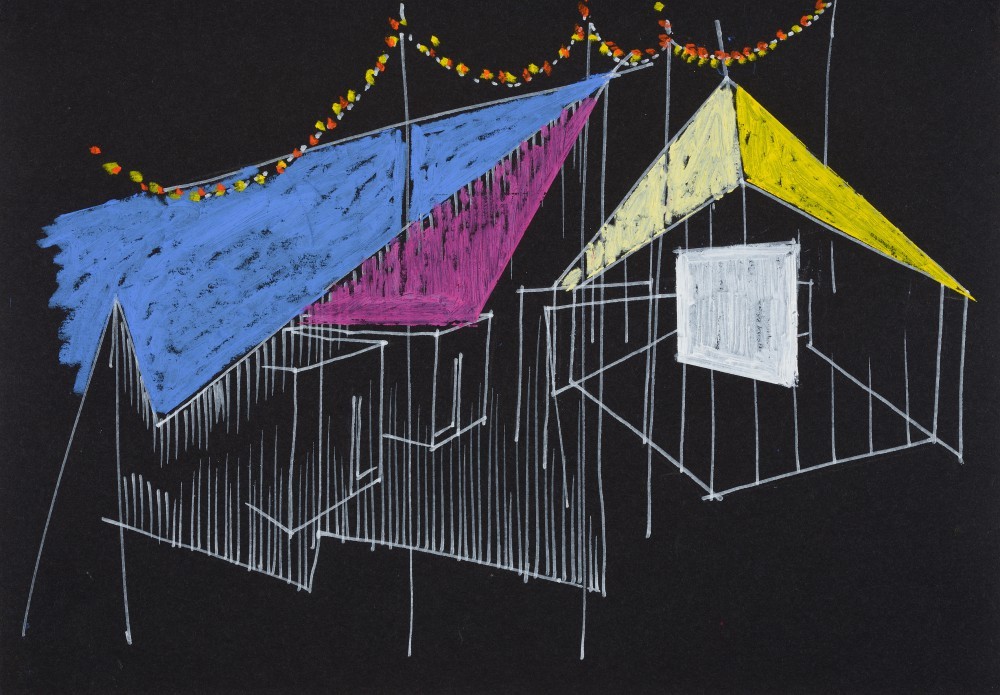

Studio Aakkerhuis Re-Générations Biennale Architecture Lyon, 2017 © Vincent Bergeron.

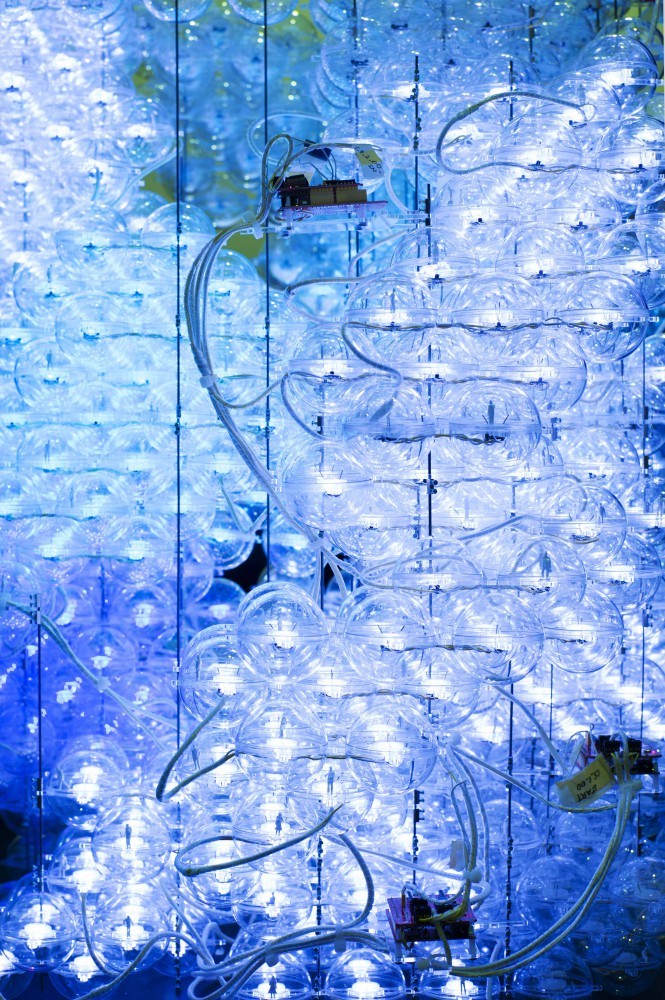

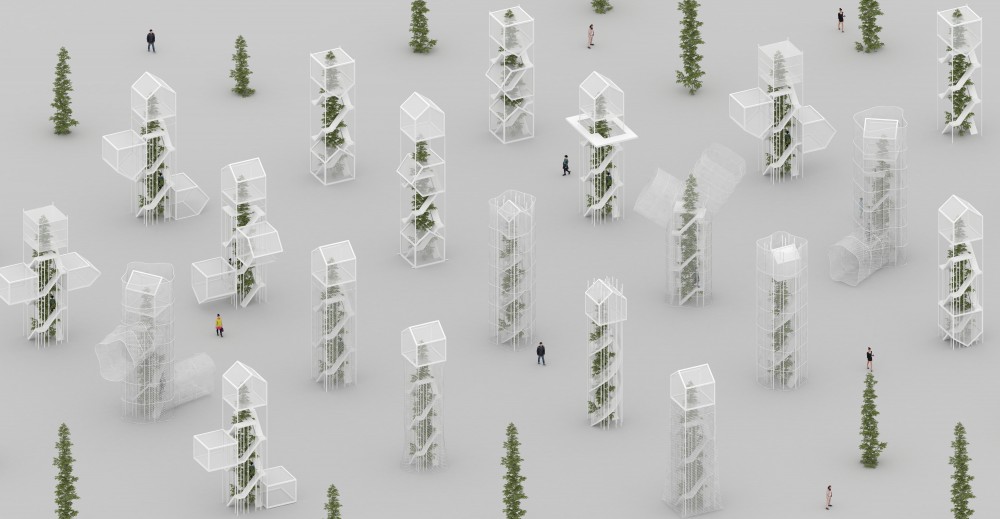

Lyon was among the first of this year’s crop, in June, in what turns out to be a city of biennials: the Capitale des Gaules already hosts an art biennial (since 1991) and a dance biennial (since 1984) — as ever, architecture is the last to catch up. Founded by local architects Isabelle Leclercq and Franck Hulliard, this first edition invited participants to think about how architecture will rise to the environmental and societal challenges of the future. On display in La Sucrière — a former warehouse in Lyon’s redeveloping Confluence district (whose flagship is Coop Himmelb(l)au’s ridiculous Musée des Confluences) — the exhibits were, for the most part, predictably worthy and didactic. There were a few exceptions, however. Paris-based Studio Akkerhuis — founded in 2014 by Dutchman Bart Akkerhuis, previously a partner at RPBW — literally took the whole thing as a game with their interactive “utopian” installation Re-generation: players were invited “to deal with simulated problems and chain reactions while always facing the so-called ‘earth exceeding date,’ representing the stage beyond which the planet’s annual capital of regeneration will be exhausted. A game is won once a player manages to postpone this point of no return by innovating and finding solutions to the different issues at stake.” To what extent the simulations really represented the earth’s parlous state probably wasn’t the point: the game got people thinking about environmental questions and beeped and blinked and lit up beautifully while they did so. Laisné Roussel, another Parisian firm, also opted for the ludic approach with their Pavillon des Fleurs, a sort of white-metal open-work Wendy-house tower, with a spiral stair inside, slides at its lower levels, and plants everywhere. An economical structure built in partnership with greenhouse manufacturer M-Tech, it probably won’t do much to save the planet either, but it sure looked pretty standing tall on the quayside outside La Sucrière. Back inside, the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne’s Structural Xploration Lab had attempted a similar exercise in structural economy with a dome made entirely of recycled skis — there may be quite a few of them to spare if the Alpine glaciers retreat any further. Meantime, just next door, the research collective SOL invited visitors to think about “soil” in all its forms — especially how we move it — while in a neighboring room eco-artist Thierry Boutonnier, in partnership with Fabriques Architectures Paysages, demonstrated some of the building materials we can grow in it, particularly linen and hemp to make insulation. Indeed their demonstration was very literal, for not only were said insulating materials to be found inside La Sucrière, they’d also planted the crops in question on a nearby wasteland site. To mark the biennial’s close, they’d planned a public harvest, but hadn’t factored in the zealous local police who, mistaking the hemp for cannabis, grubbed the whole lot up in the space of a night.

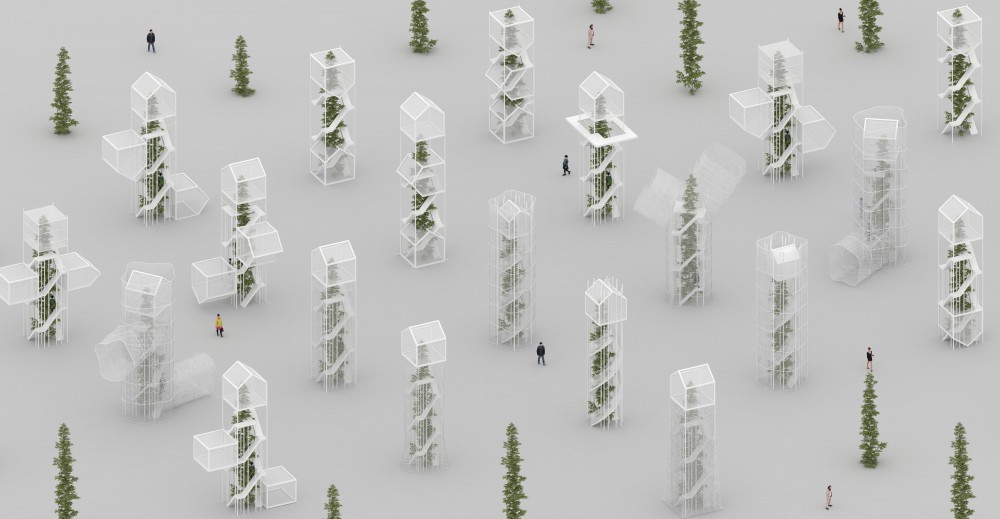

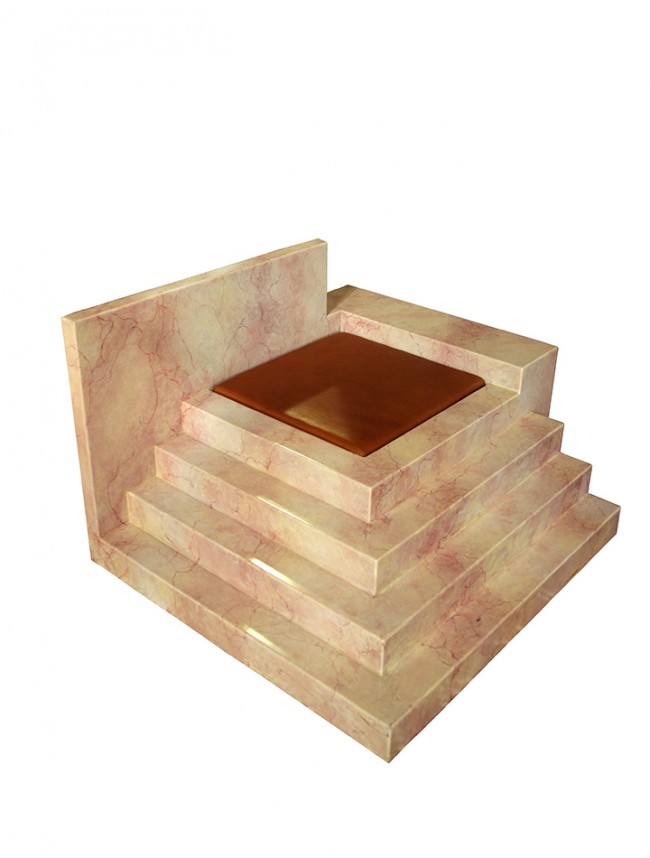

Laisné Roussel, Flower Pavilion, Biennale Architecture Lyon, 2017.

Where Lyon was often young, to a large extent local, and featured input from architecture schools, the Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB) is all about a certain international jet-set, even if, refreshingly, the real oldies and starchitects are mostly absent from this year’s edition. Well on their way to being establishment, and certainly not radical in any of the traditional senses of the word, this lot form what you might call the middle guard (but then, in our post-avant-garde age, what else could this generation hope to be?). Curated by Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee of L.A. firm Johnston Marklee, this second CAB takes the title Make New History, a quote borrowed from artist Ed Ruscha. But rather than futuristic visions of tomorrow, it turns out that what Johnston and Lee had in mind for North America’s biggest architecture event was an examination of how practices use and incorporate history in their everyday design process. Press reactions to the show have mostly been a little muted, sometimes slightly negative, and occasionally puzzled — although it’s clear that we all enjoyed it, like some sort of guilty, shameful pleasure. Trump and climate change were most definitely not on the agenda, eschewed in favor of a certain turning inwards which, in the context of the Zeitgeist, might appear a little head-in-the-sand. “If architecture as intellectual inquiry (biennials, academy, books) and profession (high rises, houses, mini-malls) is to continue to carry meaning it needs to take more risks and find allies in resistance. History — new, now, and otherwise — has never been a safe space,” wrote Mimi Zeiger in reaction on Dezeen. Frieze’s Evan Moffitt felt that “Johnston and Lee have traded the political for the pretty,” and regretted that the event did not, in his opinion, address the black populations of Chicago’s Southside. Ian Volner, in Artforum, wondered at a discipline “chasing its own tail” (he could equally have written “tale”) that perhaps, “chillingly,” might have exhausted itself, while Matthew Messner and Matt Shaw in The Architect’s Newspaper felt the history theme was essentially irrelevant and wondered, “Will summer vacationers Gary and Sheila from Waukesha, Wisconsin, understand — let alone care about — the exhibition?”

Gerard Kelly Performance at the Farnsworth House. Photo by Bradley Glanzrock courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017.

But of course Gary and Sheila aren’t the point, and this is what we all so guiltily understood: the audience is us, the international architecture geek gang that spends its time going to all these biennials and triennials. If the history theme was chosen, it was in the context of what’s been going on recently in Venice, Lisbon, or Oslo. “Since Aravena did ‘Let’s save the world’ last year, we need to do something else,” you can hear the curators thinking. Rowan Moore, writing in The Observer, summed up the CAB mood very elegantly: “There’s a group that’s not a group, a movement that doesn’t call itself a movement, an affinity of architects, a ‘constellation’ as one of them calls it, whose time has come. It has been gathering influence for years if not decades and is known among architectural cognoscenti to the point where it is almost old hat, but it is at the moment when it is starting to shape buildings and bits of cities in ways that everyone else might notice. These architects pay close attention to the fact and detail of the making of buildings — with what actually happens when something is made in one way rather than another, with the properties of scale, light, proportion, and material. Their interest isn’t just technical or about craft, but is motivated by the human and social qualities, the physical, emotional, and intellectual interrelationships that a built space can encourage. So they combine a care about the specifics of architecture with an awareness of the world beyond it, of both other forms of art and of the everyday.”

Installation view of AGENdA - agencia de arquitectura. Steve Hall © Hall Merrick Photographers, Courtesy Chicago Architecture Biennial 2017.

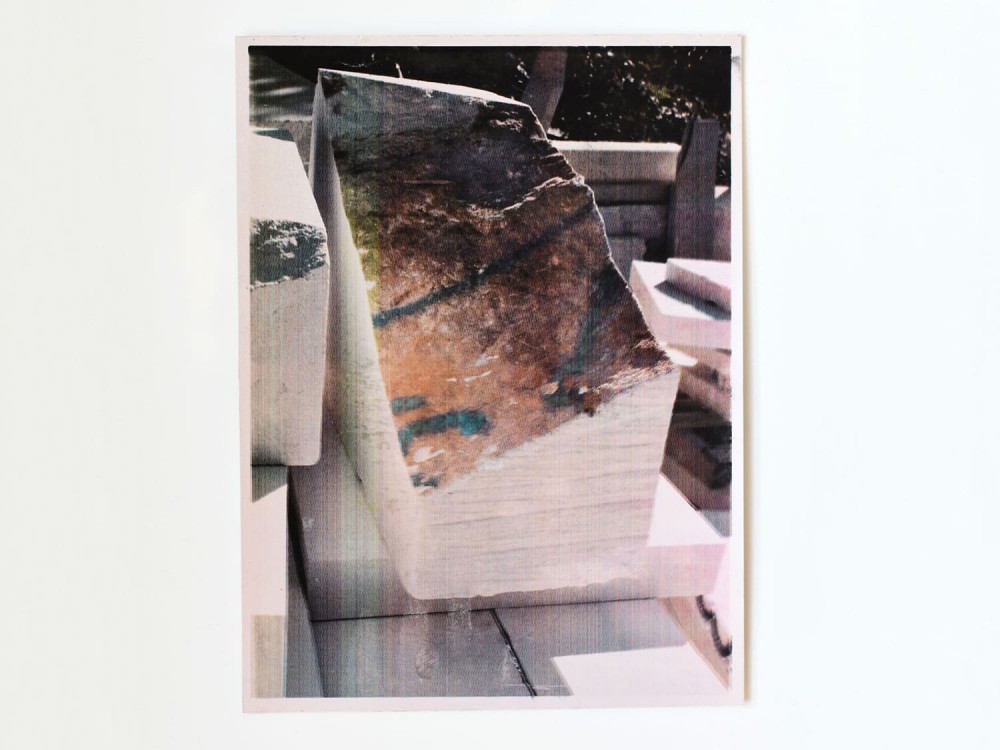

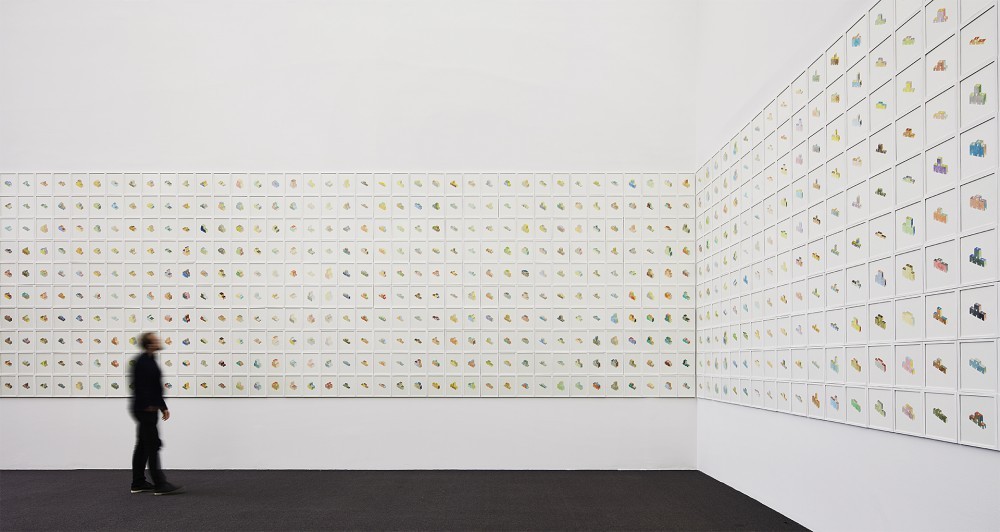

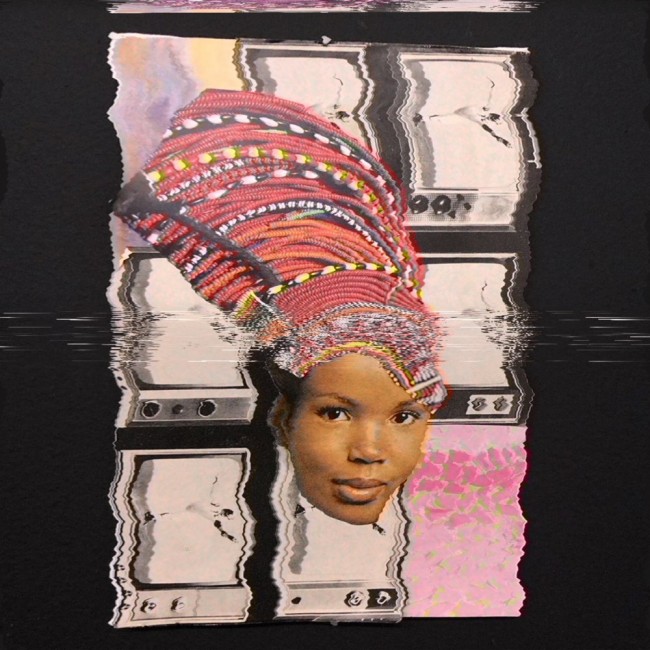

Moore also hit the nail on the head when he spoke of “an awareness … of other forms of art.” Like several of the firms they invited to Chicago, Johnston and Lee were part of a group of 100 architects who, in 2008 (when they were all still babies in architectural years), were invited by artist Ai Weiwei to design villas in the wastes of Mongolia (the ill-fated Ordos 100 project), an example of the bleeding of the realm of art into architecture that, almost a decade later, is everywhere palpable at this biennial, especially since its opening was deliberately timed to coincide with Expo Chicago, the Midwest’s biggest art fair. This overlap could be felt in many of the exhibits on show at the Chicago Cultural Center — let’s take, as a non-exhaustive selection, Jorge Ortero Pailos’s latex-cast series entitled The Ethics of Dust, Charlap Hyman & Herrero’s exquisite miniature recreations of Yves Saint Laurent’s art-filled salon being emptied after his death, June14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff’s recreation of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, or baukuh and Stefano Graziani’s Chapel for Scenes of Public Life — but also at off-site events such as SO-IL and Ana Prvački’s music-and-movement performance at the Garfield Park Conservatory (watch the video here), Gerard and Kelly’s music-and-dance performance at the Farnsworth House, Jeanne Gang and Nick Cave’s music, dance, and costume performance at Navy Pier, or even PIN–UP’s humble little stand at Expo Chicago and the talk that editor Felix Burrichter gave with artist David Hartt (whose current exhibition at Chicago’s Graham Foundation examines an aborted Puerto Rican attempt to build a Habitat 67-style housing complex). One major coup, in this beautiful but segregated city, was the opening — at last! — of The Roundhouse in Chicago’s Southside (which is part of the DuSable Museum of African American History), with an exhibition coproduced by Expo Chicago, CAB, the Institut Français, and the Palais de Tokyo. To what extent the show, Singing Stones (designed by local architect Andrew Schachman), engaged with its host community is up for debate, but the symbol of its presence there was potent.

View of the Singing Stones exhibition at The Roundhouse, part of the DuSable Museum of African American History, Chicago. Photography by Tom van Eynde.

But if you want to think about the relationship between art and architecture even further, go to the Biennale d’Architecture d’Orléans. Organized by the FRAC Centre-Val de Loire, this show makes absolutely no pretense of attempting to address its host city. Indeed the presence in Orléans of the FRAC Centre and its extraordinary collections is one of those strange quirks of historical irony. Located just an hour away from Paris by (slow) train, Orléans has a reputation for dull, bourgeois, Catholic, conservative provinciality — legend has it the town refused the TGV for fear of Parisian contamination, and while its historic heart has kept a certain superannuated charm it was never, at any point in its 2,000+ years of existence, a site of great architectural interest. When, in the 1980s, French culture minister Jack Lang founded the fonds régionaux de l’art contemporain (FRAC) — a contemporary-art acquisitions policy to be enacted by each of France’s régions — it was naturally Orléans, capital of the Région Centre-Val de Loire, that became home to the local fonds. In 1991, on the advice of Frédéric Migayrou (today head of architecture at the Centre Pompidou), the FRAC Centre decided to orient its collections towards the relationship between art and architecture, and in particular radical architecture of the post-war era, an astute move at a time when yesterday’s avant-garde hadn’t yet become fashionable and prices were still relatively cheap. The result is an unbelievably rich cross-section of the era represented by everyone from Superstudio and Archigram to the Bechers and Madelon Vriesendorp. In 1999 Migayrou and the then FRAC Centre director, Marie-Ange Brayer, launched Archilab, a biennial-like event held in Orléans that initially took place annually, then biennially, then every three years, before petering out after its last edition in 2013 — the same year that a permanent home was opened for the FRAC Centre in a converted military building with a new “digital” extension (“Les Turbulences”) by architects Jakob + MacFarlane. (The extension turned out to be a mistake — the worst of post-Bilbao formalism, formulaic and impractical — but it does a great job of épater les bourgeois, locals having nicknamed it la verrue (the wart).)

Installation view of Caruso St John with Thomas Demand and Hélène Binet, Constructions and References, 2017, Courtesy of Chicago Architecture Biennial, © Tom Harris.

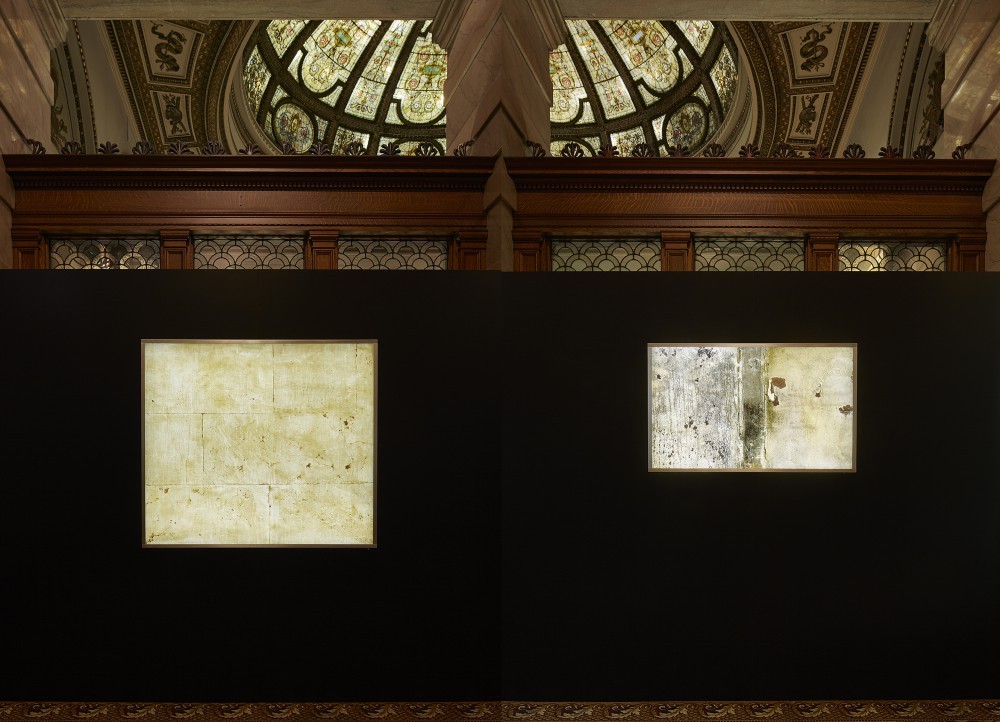

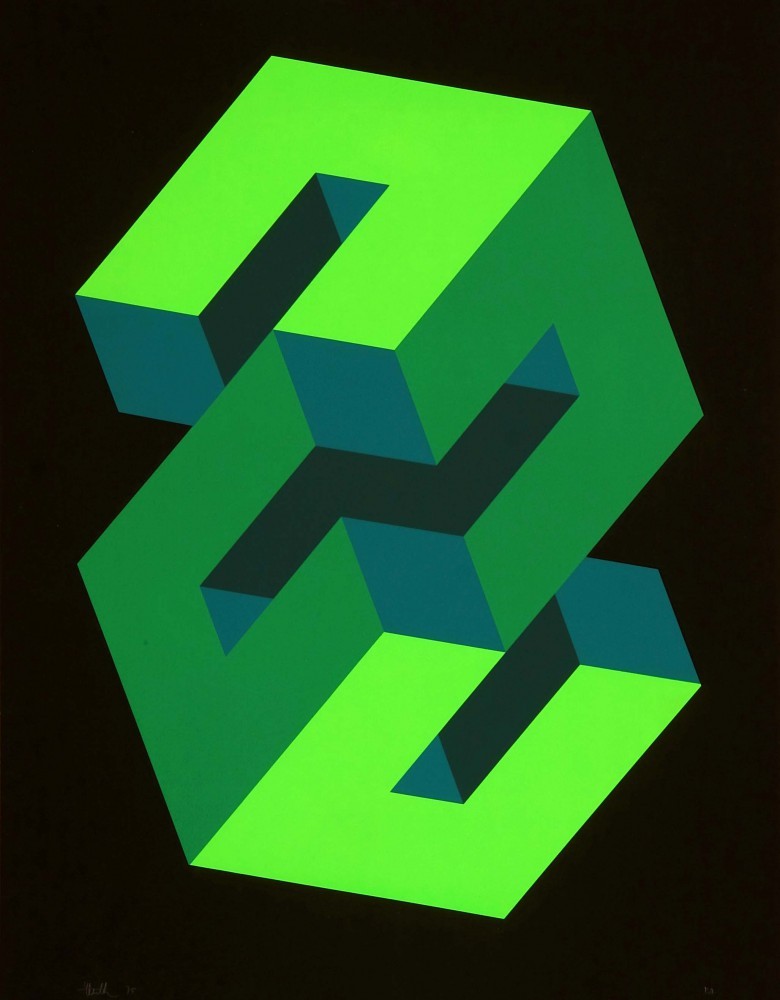

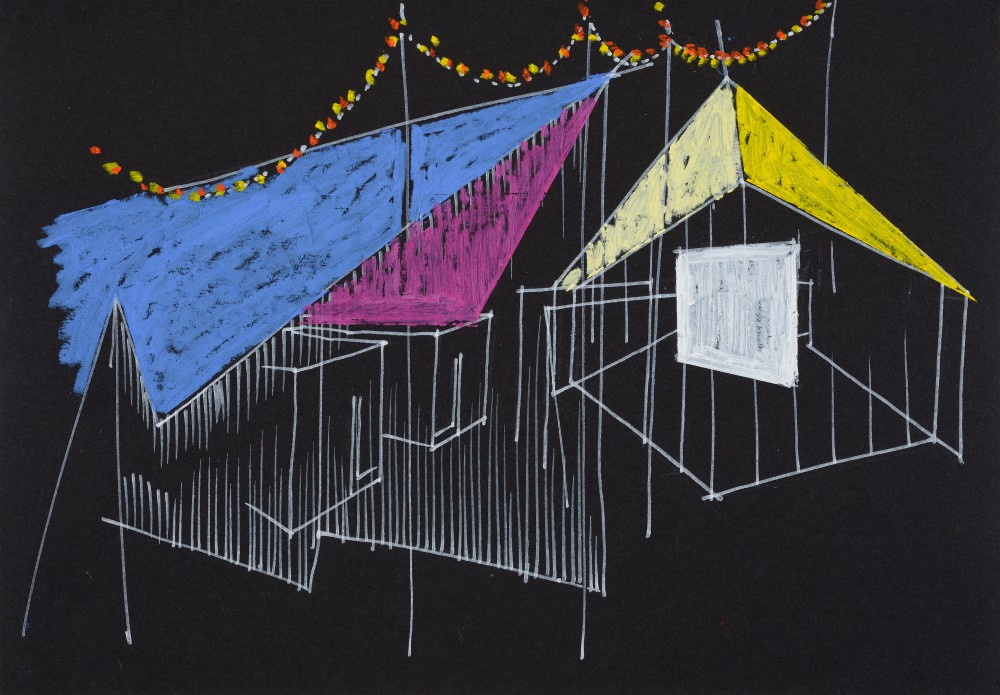

When Abdelkader Damani took over at the FRAC Centre in September 2015, he decided it was time to resurrect the success of Archilab, but this time in biennial form — and so the brand-new Biennale d’Architecture d’Orléans was born, whose first edition opened in November. Jointly curated by Damani and Luca Galofaro, it takes the title Marcher dans le rêve d’un autre (literally “walking in someone else’s dream”) and, mixing pieces from the collections with newly commissioned work, revisits some of the utopian architectural visions of the 50s, 60s, and 70s through a subtle process of juxtaposition. To give one poignant example: inside Les Turbulences, the collective Pôle d’exploration des ressources humaines (PEROU, which is headed by landscape architect Gilles Clément) have installed their detailed studies of La Jungle — the self-built refugee settlement in Calais which was destroyed by the French authorities last year —, which are paired with Constant’s Construction avec plans incurvés (1954), a sculpture that has been read as an experimental precursor of his famous New Babylon project for an anti-capitalist city (1956–74). Elsewhere you might find Archizoom’s No. Stop City (1969) dialoguing with Minimaforms’ Emotive City (2015) or Chanéac’s Ville alligator (1968) conversing with Saba Innab’s Tomorrow, Poetry Will (Not) Be The House of Life (2017). On the upper level there is a whole exhibition on the work of guest of honor Patrick Bouchain (curated by Damani and Aurélien Vernant), a French architect famous for his participative, political projects whose better-known realizations include the Lieu Unique arts center in Nantes or the Académie Fratellini circus school in Saint-Denis. Present at several sites around Orléans, including its Médiathèque and the Collégiale Saint-Pierre-le-Puellier, the biennial cocks one final subversive snook at the mentality of its conservative host town in the very grand rue Jeanne-d’Arc, which leads to the Cathedral of the Holy Cross and is lined with flagpoles that were installed for the city’s Joan of Arc celebrations which take place each May (Joan being a very Catholic and traditional figure, who’s also an age-old symbol of French nationalism and a heroine of the far-right Front National party): on said poles, the curators have paid a distinctly profane homage to the Spanish experimental scene with a series of flags, each of which depicts a different artwork, from José María Yturralde’s beautifully abstract Figura imposible Prova (1972–73) to Ana Peñalba’s Histoires de déchets (Stories of garbage, 2017).

Exhibition view of La Biennale d'Architecture d'Orléans, 2017. Frac Centre-Val de Loire © Blaise Adilon.

As I write these lines, there’s no doubt some PhD student somewhere busy beavering away on the how, when, and wherefore of design and architecture biennials and their significance in contemporary practice. Two things seem certain: that local authorities in the host cities are always part of the equation, peddling the soft power of the municipalities they represent, and that once again there is an art-world connection, the very model of the biennial having been borrowed from contemporary art. Indeed the latter realm has already begun its analysis of the phenomenon, both via publications — for example Charles Green and Anthony Gardner’s Biennials, Triennials, and Documentas: The Exhibitions That Created Contemporary Art (Wiley, 2016) — or through institutions such as the Biennial Foundation or the International Biennial Association. While there are clearly big differences between what art biennials and their architecture equivalents achieve — contemporary art is all about big bucks in the form of the “art market,” while architecture is about big bucks in a very different economic model — there are clearly strong parallels. As Terry Smith, Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory at the University of Pittsburgh, wrote last year in a piece for the Biennial Foundation:

“When we look back at the century plus history of recurrent survey exhibitions of contemporary art — those we call biennials, triennials, and (at Kassel, itself expanding) documentas — we can see that they slowly established a set of distinctive protocols, that were formalized during the 1980s, then rapidly replicated throughout the world, while at the same time steadily increasing in size and scope … it is precisely their core format, one that offers the reliable repetition of unpredictable difference, which secured their relevance, enabled their expansion, and may ensure their longevity … biennials have become essential to contemporary art’s evidently international character, many would say its ‘globality’ … (the biennial) offers, in one place, a display of the contemporary art of the world in ways that are entertaining, instructive, and competitive all at the same time … They are a double-sided form, reliable in their recurrence, but open-ended in their actualization. We do not know what art will be like two years from now, but we can expect that it will be different. Therefore, biennials can be counted on to build anticipation beforehand and to surprise us when they happen. A regularly timetabled openness to contemporaneity … is the second most distinctive feature of biennials.”

Patrick Bouchain, Centre Pompidou Mobile, s.d. Collection Frac Centre-Val de Loire. Biennale Orléans 2017.

Just as in the art world the mother of them all was Venice — the Venice Art Biennale can trace its origins back to 1895 — so it is in architecture, today’s Venice Architecture Biennale being the oldest of them all, dating back almost four decades to 1980 (although architecture was present even earlier than that as a separate section at the Art Biennale from 1968 onwards). And of course among its many upcoming delights, 2018 will be bringing us the 16th edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale in May (curated by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton), but also plenty of others besides: the new Madrid Design Week in February, the London and Istanbul Design Biennials in September, the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam in May, the Iranian National Biennial of Architecture, Urbanism, & Interior Design at some point, and, sign of the times, the very first Dubai Architectural Biennale (whose exact dates have yet to be confirmed but will take place in the fall). Just as with art, we don’t know what architecture will be like in the future, although it’s probably fair to say that, barring some radical technological innovations, its evolution will be slower. But change it will, and perhaps, as in art, biennials, triennials and their ilk will become an essential component in that process.

Text by Andrew Ayers.

The Chicago Architecture Biennial runs through January 7th, and the Biennale d’Architecture d’Orléans through April 1; both have a host of events and talks programmed between now and their close. The first Biennale d’Architecture de Lyon ran from June 8 to July 9, 2017.