ART, DESIGN, ARCHITECTURE: The Lake Como Design Fair Does it All

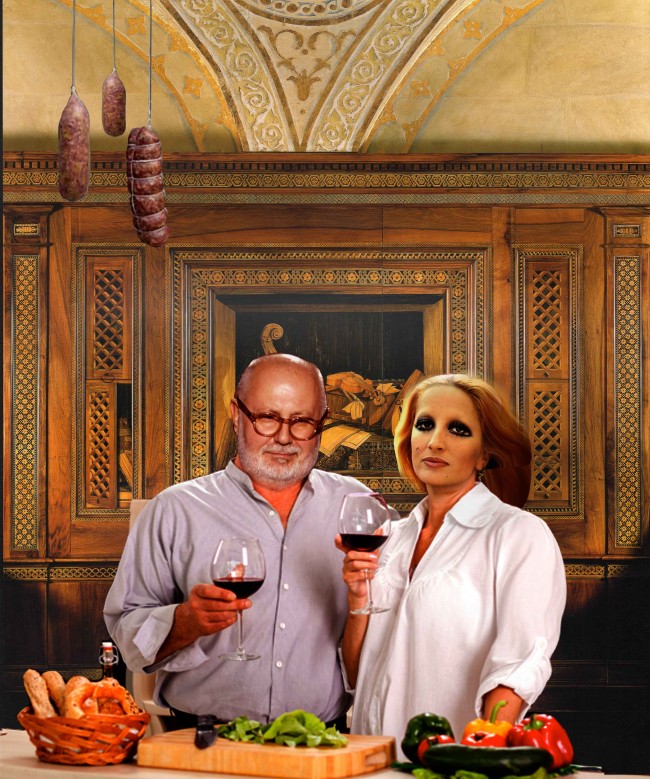

Where in the world could you buy a chair by Ettore Sottsass, a drawing by Giò Ponti, a prototype bookshelf by young design team studiointervallo, and a birdbox by French architect Rudy Ricciotti, all at extremely affordable prices? The answer is the Lake Como Design Fair, which recently held its second edition in the northern-Italian town of Como. Founded by creative director, photographer, and designer Lorenzo Butti and architect, design producer, and curator Margherita Ratti (who is based in Paris but grew up in Como), the fair, as Ratti explained to PIN–UP, aims to fill something of a gap in the supply-and-demand chain. Her experience running her own Paris space, for which she produced pieces by young designers, taught her that the gallery model has perhaps had its day in our age of online sales, the overheads being simply too high to make it viable. The fair model, on the other hand, keeps the dream alive while significantly reducing costs for Ratti, allowing sale prices to be reduced too, and ensuring international exposure for young creators seeking production contracts. And then there’s the beautiful city of Como — birthplace of the Futurist Antonio Sant’Elia and a hotspot of Italian Rationalism after Giuseppe Terragni set up shop there in 1927 — which makes for a refreshing and picturesque change from the saturated marketplaces of Paris and Milan, but is still accessible to French and Italian buyers as well as to nearby Swiss, German, and Austrian collectors.

-

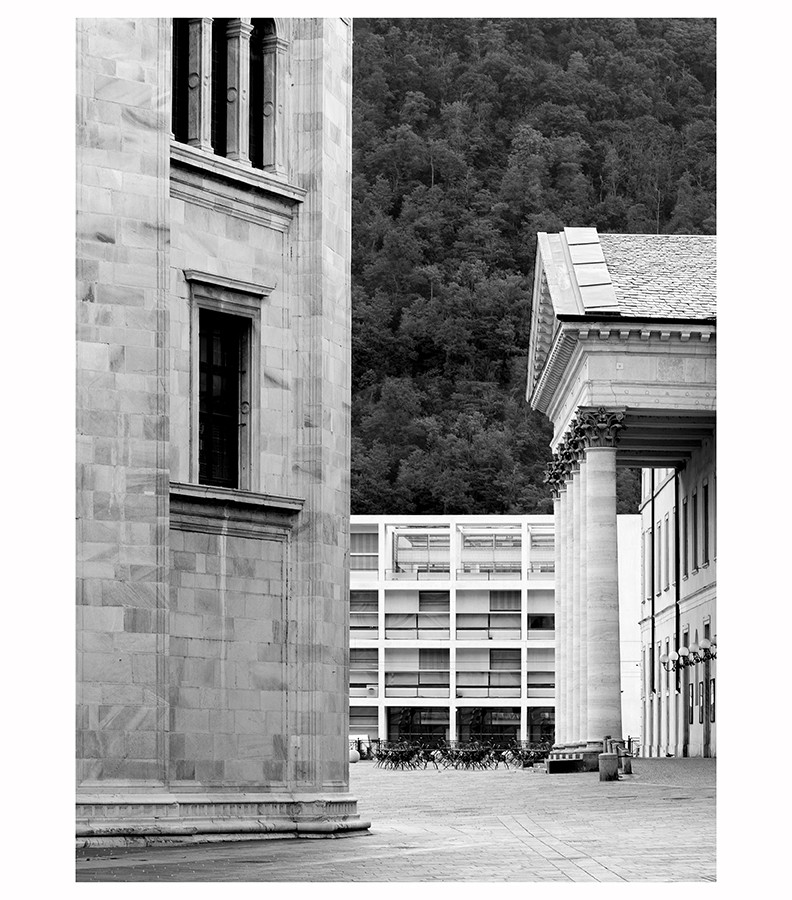

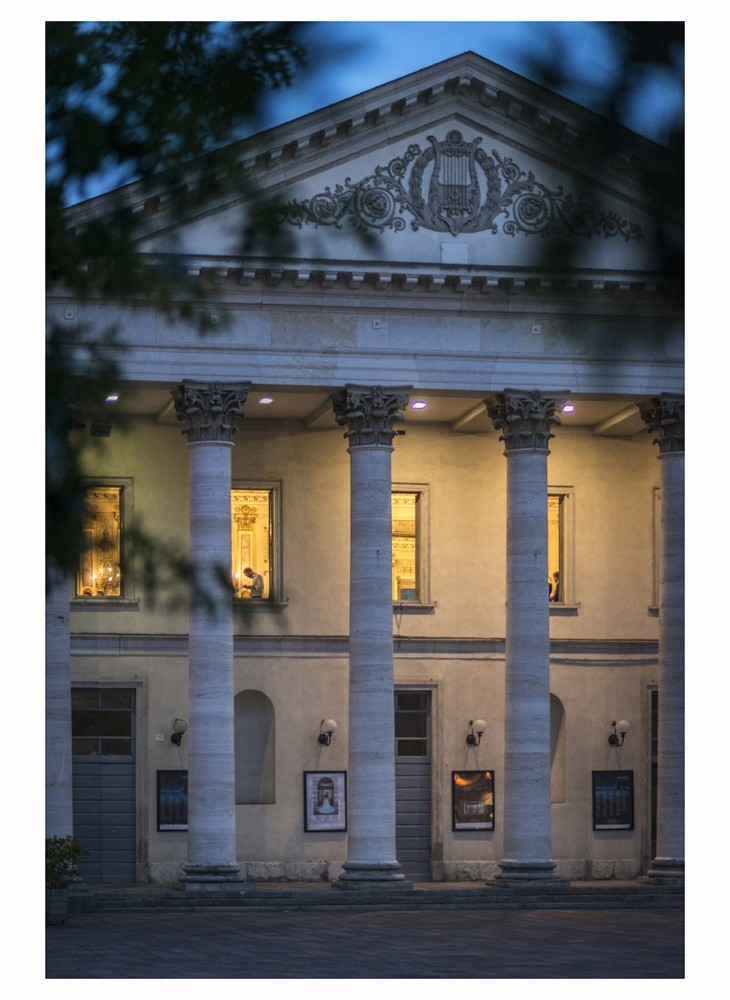

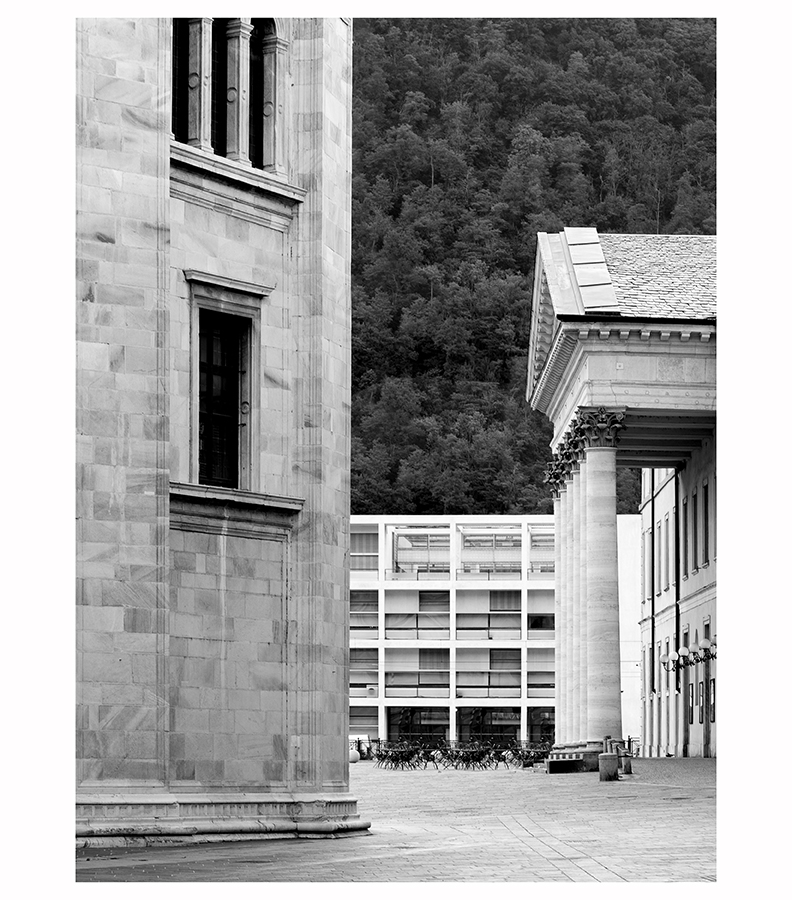

The Teatro Sociale in Como, Italy (right) with Giuseppe Terragni Casa del Fascio (1936) in the background. © Francesco Arena

-

Palazzo del Broletto in Como, Italy, where the architecture section of this year's Lake Como Design Fair took place. The exhibition was curated by Andreas Kofler of the Swiss Architecture Museum (SAM) in Basel.

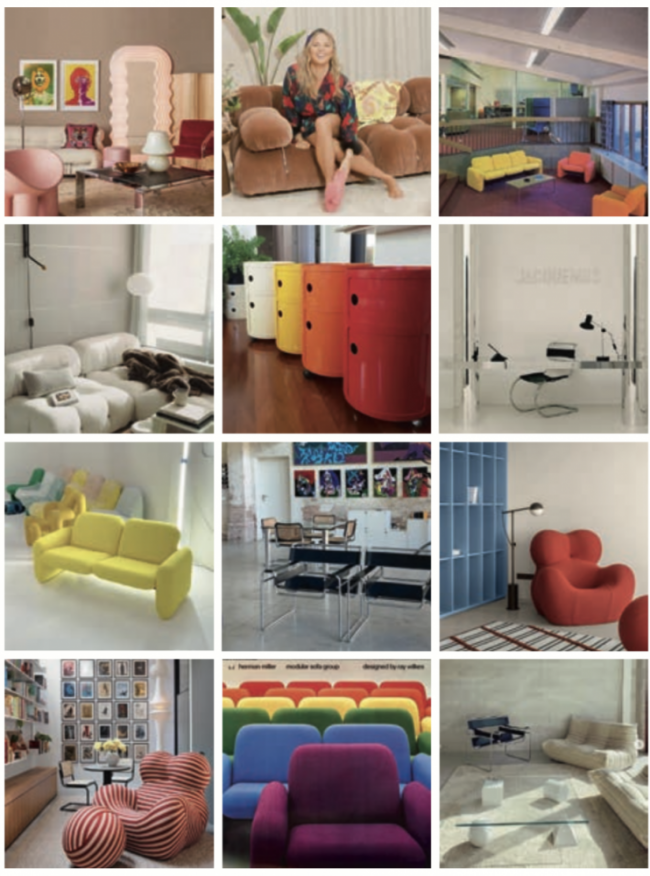

For its second edition, the Lake Como Design Fair was divided into two parts: a design section, curated by Ratti, displayed in the sumptuous and usually inaccessible salons of Como’s early-19th-century Teatro Sociale (one of the few remaining private theaters in Italy); and — a newcomer this year — an architecture section, curated by Andreas Kofler of the Swiss Architecture Museum and shown in the Broletto, Como’s medieval council chamber just next door to the Duomo. Chosen according to a broad umbrella theme of “color,” the 120 objects on display at the Teatro Sociale ranged from industrial-design pieces — for example 1972 Model 4025 lamps by Olaf Von Bohr (offered by Demosmobilia for 400 euros each) — to prototypes — studiointervalle’s handsome Zenobia bookshelf (it seemed a shame to put anything on it), at 8,000 euros, or Juliette Le Goff and Nicolas Verschaeve’s beautiful Mirage room divider, yours for a bargain 1,250 euros — to “unique artifacts” such as Markus Friedrich Staab’s one-off alterations of standard furniture (his Fake Frankfurt chair, for example, at 3,200 euros) or Charles-Antoine Chappuis’s splendidly useless knitted vases (750 euros each). Installation view of the Lake Como Design Fair's 2019 edition in display at Sale del Ridotto Como’s Teatro Sociale. © Gianluca Bellomo

-

Installation view of the Lake Como Design Fair's 2019 edition in display at Sale del Ridotto Como’s Teatro Sociale. © Gianluca Bellomo

-

Jimenez Lai/Bureau Spectacular, Corner Splat rug (2019).

-

Studiointervalle, Zenobia shelves (2019). © Giulio Boem

Over in the architecture department, things were, perhaps inevitably, even less conventionally straightforward. For how exactly do you sell “architecture” at a design fair? The purest way, no doubt, is to offer exclusive rights to plans, and for 15,000 euros apiece (by far the most expensive items at the fair) you could purchase a box set of measured folly designs by the likes of Dominique Perrault, Beckmann N’Thépé, and Will Alsop. In addition to these, Kofler had put together an amusing and eclectic collection of objects, from drawings and photographs — perhaps the most obvious way to sell “architecture” when you’re not hawking an actual building — to models and architect-designed furnishings. Which leads to an obvious confusion of genres... Why wasn’t that stunning 3D corner carpet (Corner Splat by Urban Fabric Rugs in partnership with Jimenez Lai/Bureau Spectacular, 9,880 euros) over in the design section? With respect to that same quibble, Giò Ponti, who is best-known as an architect but was also a designer, was featured in the design section with a drawing of girls carrying sacred vessels (probably a motif for a vase, yours for 5,500 euros) — why wasn’t he in the architecture section? Ditto Sottsass’s Trono chair (298 euros), which was over in the Teatro Sociale, even though his drawings were in the Broletto, alongside French architecture/urbanism office AUC’s Augures stools (580/850 euros depending on size). And what about Mathieu Peyroulet Ghilini’s fascinating photos of contemporary Japanese vernacular buildings (500 euros each)? Not only were they taken by a designer, they could quite easily could be categorized as “art”...

-

Installation view of the Lake Como Design Fair's 2019 edition in display at Sale del Ridotto Como’s Teatro Sociale. © Gianluca Bellomo

-

Installation view of the Lake Como Design Fair's 2019 edition in display at Sale del Ridotto Como’s Teatro Sociale. © Gianluca Bellomo

-

Installation view of the Lake Como Design Fair's 2019 edition in display at Sale del Ridotto Como’s Teatro Sociale. © Gianluca Bellomo

Which brings us to the question of intention. Bar the Ponti drawing, every object in the Teatro Sociale had been deliberately made as a design object to be sold. But this was far from always the case in the Broletto. Parisian architects Abinal & Ropars were no doubt thrilled to offload a couple of their old conceptual project models — fun objects it’s true — for 6,000 and 9,800 euros apiece. Stefano Boeri’s study for the former arsenal in Sardinia (1,350 euros) was also a by-product of the design process (just like the Ponti drawing), but French architect David Apheceix had produced his two pieces (a flat print for 500 euros and a 3D print for 1,200 euros) specially for the fair. To what category should Apheceix’s objects belong? Not in any way conceived as viable buildings, but perhaps related to ongoing design research, they seem to hover somewhere between the realms of art, architecture, and design. But then weren’t some of the very impractical objects and furniture on offer in the Teatro Sociale veering towards the art side of things too? — Chappuis’s knitted vases, clearly, or Claudio Colucci’s Mutant series, whose manga-Pop hacking of Thonet chairs (2,500 euros each) resulted in objects conceived far more for the mind and eyes than the backside...

All of which goes to show just how artificial and arbitrary our divisions between disciplines really are. Does it really matter if an object is a piece of art, design, or architecture, or all three at once? On the one hand, the 2019 Lake Como Design Fair was a glorious jamboree of often ambiguous objects offered up for our aesthetic and mental delectation — stick all that in a museum and no one will bat an eyelid. On the other hand, where selling these pieces and creating a market is concerned, categories definitely seem to matter — it’s easier to put a price on something specifically conceived (and therefore marketed) as architecture, design, or art than something that hovers uneasily in between. Indeed, outside of museums, cranks, and specialists, is there really a market for stuff produced by architects that isn’t actually a building? Slow sales in the architecture section of the fair suggest the answer is perhaps “no” — or at any rate “not yet.”

Text by Andrew Ayers.