The Marbled Approximations of the Artist Lauren Clay

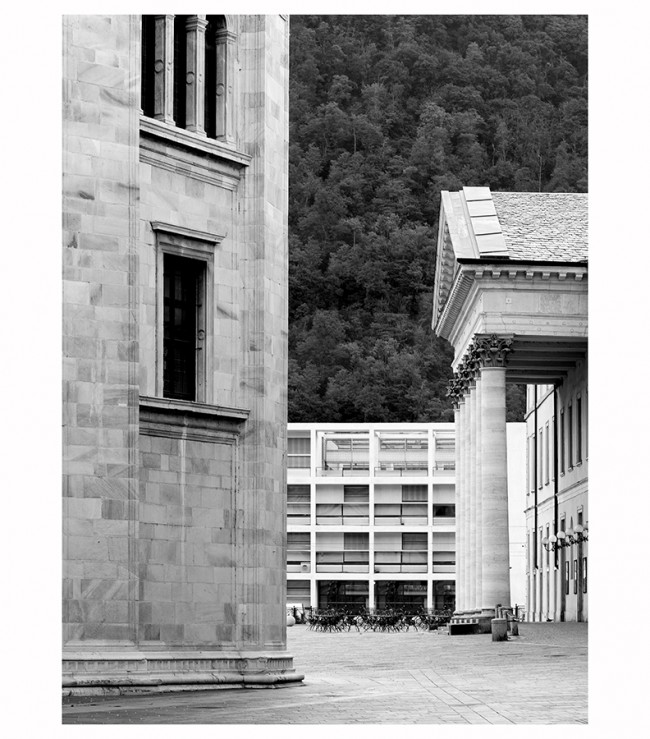

Windows and Walls, a recent exhibition at Asya Geisberg Gallery by the artist Lauren Clay, was an expert exercise in paradox. Sliding nimbly across meanings, media, and materials, the sherbert-colored sculptures and muted wallpapers created an environment all their own within the gallery space. The namesake “windows” — which recalled art nouveau, Bernini, Gothic grotesques, and Gaudí in equal measure — were constructions of oil paint, plaster, and paper pulp built up on panel into textured glowing sculptures of frames and trellises, windows that refuse to reveal. The “walls” in Windows and Walls, were the literal walls of the gallery which the windows “looked” upon and which were all covered in digitally-printed wallpaper that depict arcades, columns, and other architectural formations built in alien pastel marbles.

Though vibrant and ocularly rich, the exhibition with its windows through which nothing but the printed walls could be seen was in many ways fixated on materiality rather than vision — the way materials reveal themselves to us, and the way we manipulate them to give voice, to give them the chance to lie. The sculptures were immensely physical. Hand-hewn and tactile, they looked soft and when I saw the show I wanted to touch them. (I didn’t touch them, but I still imagine them squished under my fingers and, in my own mental fiction, rebounding like a stress ball.)

Lauren Clay, Windows and Walls (2018); Image courtesy Asya Geisberg Gallery.

Further troubling the lines between material and vision are the images on the walls. Reading the “marble” wallpaper as an exercise in straight verisimilitude would be too easy. The wallpaper’s patterns were born of a far more physical, more materially contingent act of reproduction: Clay marbled the paper herself, cut it into tiny architectural formations with an X-Acto knife, and layered the fragments together into miniature collages. She then scanned these collages, dematerializing the intimately layered paper, and later printed them enlarged several times over, making wallpaper estranged from, yet intimately tied to its physical beginnings, much as the verb to marble is born of but somehow distinct from the namesake stone it approximates. There is a truth in words, but there is more truth in what words obscure. Paper marbling, normally reserved to decorate fine books, is returned to its etymological origin, almost, reminding us that an object is always just something that happened. Much as Clay’s computer mediates material, language mediates reality. Pushed to an extreme in Windows and Walls, the boundary between world and words is worn thin. Language becomes the process of production and of perception per se. Description attempts to become the thing itself.

And in speaking, in taking up the world of and world as language, the show repeated itself, or perhaps more accurately, the paper did: paper windows, marbled paper, wallpaper. There was not just the imbrication of marble’s dual meanings, paper too sounds over and over again. Words repeat, but things speak most urgently. Clay’s investment in the materiality of language reveals the abstractness of material itself.

Lauren Clay, Windows and Walls (2018); Image courtesy Asya Geisberg Gallery.

Not satisfied with just reconfiguring material and meaning, Clay also radically reimagined scale. To make something so small (the original collages, tucked away in the back office, are about the size of a standard piece of printer paper) so large (the walls were twelve feet high) is to entirely reframe our experience — visual and embodied — of these materials and images. The handheld and handmade enters the screen to become huge IRL, and then on gallery checklists and Instagram, which is how many likely witnessed Windows and Walls, miniature again.

And there was an irreverence at play. A bit of wall that jutted into the gallery, bisecting it into two sections, had columns reproduced on all sides. However the three reproductions of columns, that felt as if they ought to align to signal a whole, refused to. Each column on each wall was different, frustrating any attempts to impose architectural coherence. Like the sculptural “windows,” these foundational elements of architecture were given the chance to become functionless; they were only gestures toward the “building” in general, the sense of being built. However, all these transformations, repetitions, mishearings, and puns were not actively trying to deceive. In fact, if you were to look closely, they were almost too honest. What at first seemed to be, and what if we glanced to quickly, we could choose to accept as, a play with perspective on the wallpaper — columns that didn’t quite add up together, warped perspective — was revealed to be just a consequence of originally working so small with a material as unforgiving as paper. You could even see spots where there are uneven cuts, accidental tears, only now they were rendered flat, a marbled texture thrust into a (literally) post-digital void only to be spat back out. Liberated from their function Clay’s “windows” and “walls” reminded us that in a world so constantly mediated by words, images, and the media they travel on, much of what we hear, see, and say is, at best, an approximation.

Text by Drew Zeiba.

All photos courtesy Asya Geisberg Gallery.