COACHELLA THROWBACK: The Festival’s Art of the Desert Folly

Contrary to the smiling faces and flower crowns that temporarily subsume Instagram, a day at Coachella is a brutal thing. Take its most recent iteration, which took place for the 19th time in April this year and during which hundreds of thousands of bodies were again trapped for two days in a literal desert, saddled with limited cell phone service and a list of directives to minimize the threat of heat stroke:

- Drink water

- Apply sunscreen

- Charge your phone

- Survive until Beyoncé

In real life, the glittery women with mermaid hair keep their faces covered with bandanas to keep out swirling clouds of dust. The vibe is Mad Max with Adam Selman glasses, a fashion dystopia amplified further by the presence of large-scale, post-apocalyptic art that always dot the dusty festival grounds similar to follies would be dispersed throughout an 18th-century landscape garden. In 2018 Simón Vega, an artist whose Tropical Space Proyectos is an ironic meditation on the Cold War’s effects on his native El Salvador, installed a likeness of the Mir space station clad in the corrugated surfaces of a Central American shanty town. Looming 50 feet tall and 150 feet long, his Palm-3 World Station prompted an important question: If shit were to really go down, would this be our way out? Nearby, artist Randy Palumbo’s Lodestar — a chrome-finished Lockheed Martin Lodestar jet ominously positioned at a nosedive into the grass — dampened any hope for a successful escape.

Lodestar (2018) by artist Randy Polumbo.

These large-scale works of art arrived at Indio, California’s Empire Polo Field neither by space flight nor world-ending catastrophe, but by the concerted effort of Coachella’s artistic direction. For the past several years, Coachella’s organizers diverted their approach from the recycling of works that had debuted at Burning Man in nearby Nevada to the commissioning of exclusives by interdisciplinary professionals. Recent editions of Coachella have seen pieces by designers and architects such as Philip K. Smith III (2014), The Haas Brothers (2015), Chiaozza (2017), Jimenez Lai (2016), artists Katrīna Neiburga and Andris Eglītis (2016), artist and urban theorist Olalekan Jeyifous (2017), and Katie Stout (2018), scouted at destinations like Frieze, Design Miami, and the Venice Biennale.

“Working with artists who aren’t in this setting already lends itself to something that is distinct and unique,” says Coachella art director Raffi Lehrer, former head of production at the Haas Brothers’ studio. In the hashtag-driven age of Instagram, visuals are what distinguish one festival from another in the collective consciousness. Especially for artists working in the institutional sphere, the draw to the less erudite platform of Coachella is in the sheer scale and quality of the production value (reportedly, a six-figure budget proposal ain’t no thang).

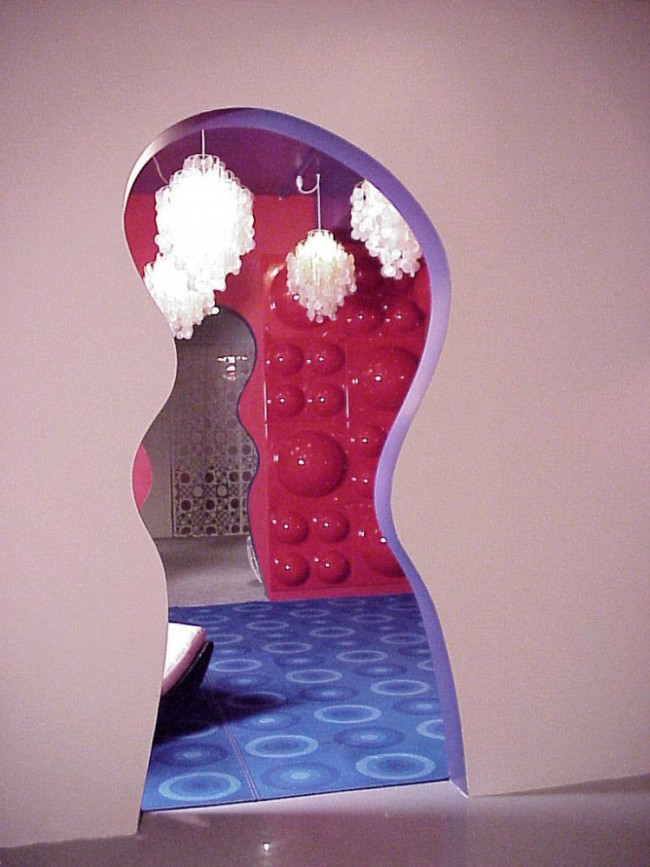

Edoardo Tresoli's Etherea (2018) consists of a row of three progressively sized neoclassical domes in porous wire mesh.

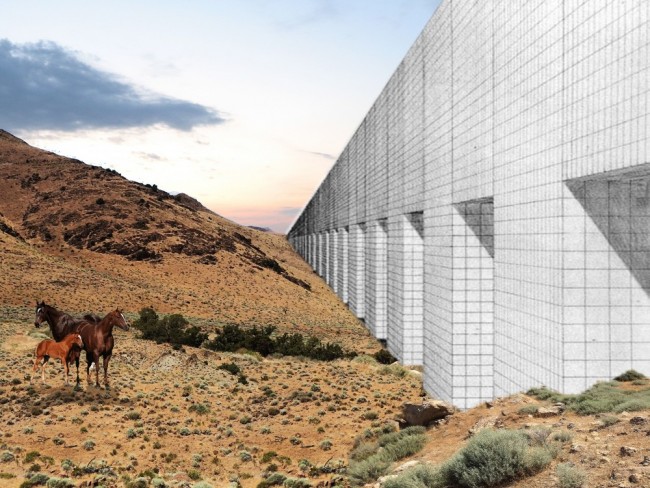

For Brooklyn-based artist Olalekan Jeyifous, it segued his practice of speculative urban planning in the face of income inequality from digital collage and sculpture to large-scale public artwork; his 2017 Crown Ether was the abstraction of a built community made inaccessible by being raised on stilts. Jimenez Lai’s largest work to date was his 2016 Coachella commission, The Tower of Twelve Stories, a slouching, 52-foot-tall caricature of an apartment building. Its incongruous, round-edged units, stacked precariously at a tilt, were the built response to the neutral rationality outlined the 1993 Rem Koolhaas essay “Typical Plan” about the repetitive homogeneity of the Manhattan’s office layouts. On the polo field, they both occupied a space of conceptual exploration — although, to most, it was a cool background for selfies.

The superficial nature of the selfie is the defining feature of Coachella culture for the greater art world, which sometimes regards public art with the same disdain as pop music: its appeal broad rather than cultivated, oversimplified for mindless public consumption. Reduced, basically, to cultural junk food. But it would be remiss and exceedingly square not to acknowledge Beyoncé’s performative genius as a true work of art. At Coachella, the delineation between so-called high and low culture seems outdated, a self-imposed barrier to fun.

Simón Vega's 150-feet-long Palm-3 World Station, photographed before the onslaught of Coachella's 200,000-plus visitors.

Speaking of non-delineation, Milan-based artist Edoardo Tresoli describes his 2018 Etherea, a row of three progressively sized neoclassical domes in porous wire mesh, as being “permeated by the boundless California landscape and skies.” It’s also permeated by the signifiers of Southern California in the popular imagination, a transgression into the old world by the Postmodern — that is, an appropriation of aesthetics that here at Coachella range from Woodstock, Day of the Dead, cattle ranching, various indigenous cultures, and Light and Space. In the shadow of Tresoli’s skeletal remains of an ancient city, it’s a party you want to experience at least once.

The artist Rachel Whiteread once articulated her disdain for “plop art,” the increasing phenomenon of public art in which, “you plop a piece of work down in a place and it doesn’t really bear any relationship to anything else.” The results are ill-conceived, non-contextualized, and rarely noticed. On the contrary, public art at Coachella serves a centralized function in which scale is essential as a means of wayfinding. At dusk, the sky melts through the golden hour into shades of violet and rosy gold, and the cover of darkness becomes transformative: it hides both the dust and the presence of festival bros. (Curiously, Instagram rarely shows you what happens at night.) The art forms an approximation of a skyline, with each piece illuminated with perpetually shifting Dayglo colors. It’s an oozy psychedelia, or perhaps something as benign as a child’s birthday party. (The vibe here is driven much less by mind-expansion than the straight-forward mind-altering effects of beer or pot or the desire to see The Weeknd.)

A view of Coachella's main stage (left) and the Spectra tower (right) created by design entertainment design company NEWSUBSTANCE.

Consequently, the cover of darkness also hides everything else. In the overwhelming blackness of a desert horizon, Coachella’s larger-than-life sculptures are the only visible landmarks. “Where u RN?” a friend might text after you got separated in the Yuma tent. “u wanna meet at the rainbow tower?” That particular tower was this year’s Olafur Eliasson-esque Spectra by UK-based entertainment designers NEWSUBSTANCE — a seven-story spiraling ramp with tinted windows that span the color spectrum. From afar festival-goers were able to watch the different elevations at which people inside walk in circles, perpetually moving from one color to the next, like a kaleidoscopic leaning tower of Pisa. Its image struck a familiar chord; it is, at the end of the day, finding that each of your friends is a different level of high and struggling to hold a conversation.

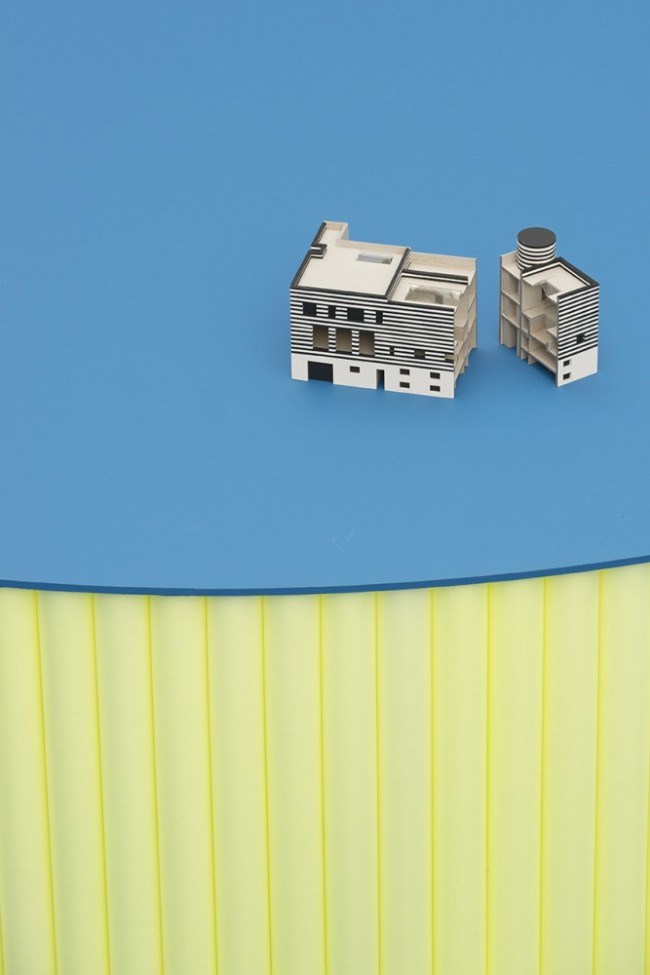

A sketch for Katie Stout's Display This Oasis, an augmented reality feature that Coachella-goers were able to see through their smart phones.

When the party ends and Coachella’s organizers ready themselves for next year’s spectacle, the sculptures from the current year are dismantled and disseminated in various ways. The reflective pieces of Gustavo Prado’s modular, 2017 Lamp Beside the Golden Door, for example, were shipped back to the Brazilian artist’s studio to be repurposed into new works, while the Seussian spectacles of Chioazza 2017 garden have been resettled onto the lawn of Hero Beach Club in Montauk, New York. As far as the pieces from Coachella’s 2018 iteration are concerned, art director Raffi Lehrer is in the process of negotiating new homes for the installations by Edoardo Tresoldi, and Simón Vega, while Randy Palumbo’s Lodestar is back at the artist’s Joshua Tree studio. Meanwhile, Katie Stout’s virtual sculpture continues to be available on the official Coachella app. Their respective returns to civilized society do disprove the old adage, however, that “what happens at Coachella, stays at Coachella.” What happens at Coachella actually lives on into eternity, if not acquired by a collector or museum, then at least immortalized on Instagram.

Text by Janelle Zara.

All images courtesy of Coachella.