POOL POLITICS: An Exhibition About the Architecture of Private Pools

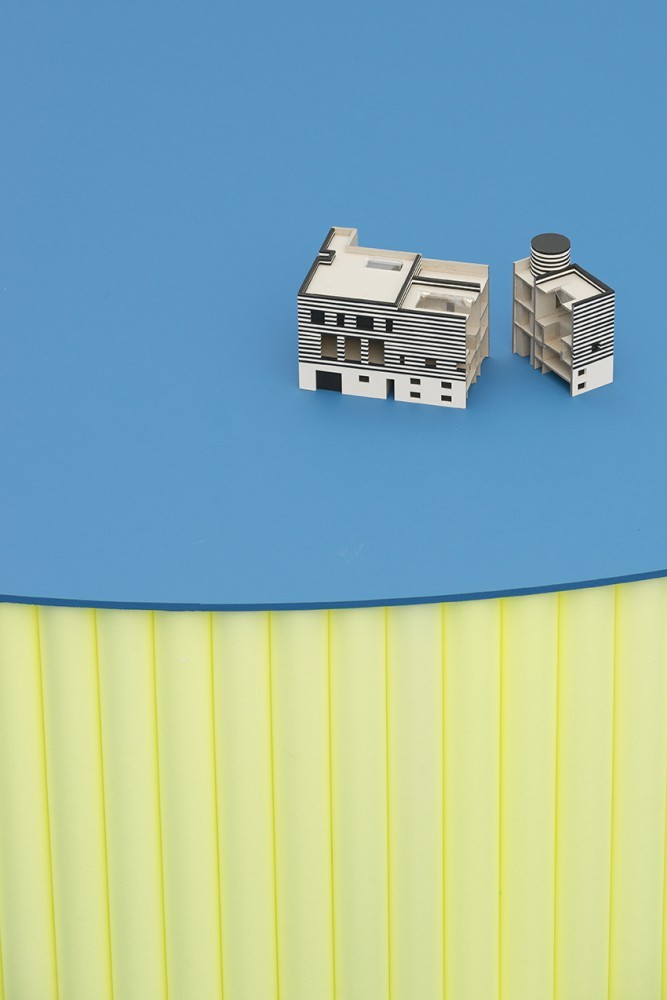

View of the exhibition Domestic Pools at the Villa Noailles in Hyeres, France.

In Man Ray’s 1929 Surrealist short film Les Mystères du château de dé, the principal character is a mysterious Modernist house whose inhabitants, their faces veiled by ladies’ sheer stockings, spend much of their time engaging in what, nearly 90 years later, seem like rather silly sports involving beach balls, gym wheels, and, crucially for our subject today, a splendid indoor pool. I say indoor, but it could also become outdoor thanks to four enormous panes of glass that wound down into the floor below so as to open up the space to the adjacent sun terrace. Further daylight flooded through the pool’s ceiling thanks to an artful geometric arrangement of concrete beams and glass bricks, which jazzed up the otherwise utilitarian white interior. The people frolicking in the film — diving from a board, leaping into the water from a trapeze, juggling underwater — were Vicomte Charles and Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles and their friends, and the house was the couple’s winter holiday home, the Clos Saint-Bernard in Hyères, France. It can still be visited today and its pool, fittingly enough, is currently the centerpiece of an exhibition retracing the history of private domestic swimming.

This is the third successive annual architecture show at the Villa Noailles (as the house is now known) to be curated by Benjamin Lafore, Sébastien Martinez Barat, and Audrey Teichmann (following Landskating in 2016 and last year’s La Boîte de nuit). Once again they’ve taken a rather neglected architectural type-form and run with it. For given the place that private pools occupy in our collective imagination (dive into PIN–UP’s POOL PARTY to see what I mean), they’ve been surprisingly ignored by critical discourse, despite there now being around 1.9 million of them in France and four million in the U.S. (the world’s two biggest builders of domestic pools). It was in the late 19th century that private pools first began to appear — like the movies, they’re synonymous with modernity — but initially they were purely the affair of the extremely wealthy. For everyone else, the hygienist craze for swimming was satisfied by the building of collective, public pools. But after World War II, initially in America but soon the world over, the golden age of the personal, private pool began. In the U.S., according to historian Jeff Wiltse (whose essay Reflections on Modern Swimming Pools appears in the catalogue), their multiplication was partly due to the increased affluence and aspiration that fueled the rise of suburban living, and partly due to racism: as official segregation ended, whites made sure they would never ever have to swim with blacks.

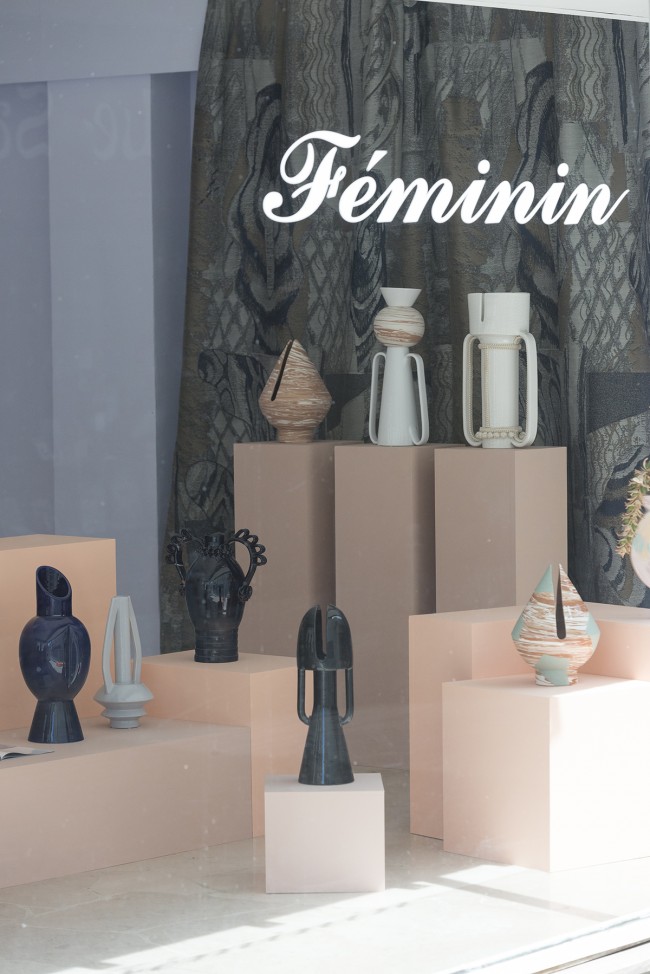

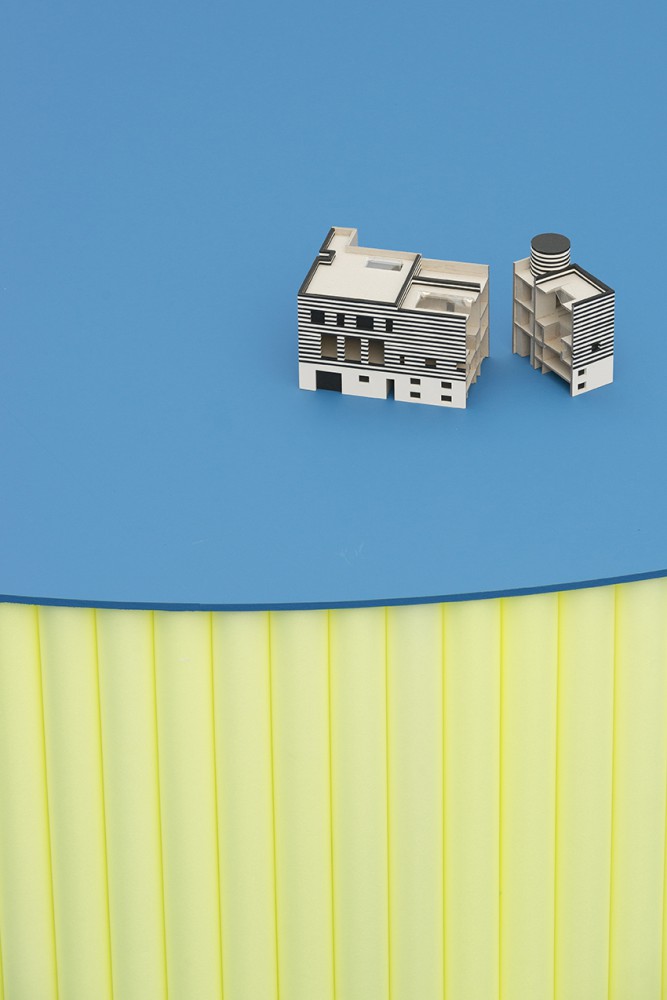

A miniature model of Adolf Loos's unsolicited design for Josephine Baker's house in Paris, 1927.

Much of the allure of private pools no doubt comes from their inherent ambiguity: on the one hand clean (sports, health, hygiene), on the other dirty (sex, eroticism, seduction); the ultimate symbol of glamor and luxury, they’re rooted in segregation and exclusion. But that allure is also a question of architecture, and, as this show demonstrates, if you have the funds, there’s no end to what you can do with a pool. The curators have categorized their subject in terms of four “figures” and divided up their show accordingly: the tank (the pool as utilitarian sports facility), the wet room (the pool as part of the house), the pond (the pool as landscaping), and the vase (the pool as decoration). While you might not always agree with the category certain pools find themselves in, the distinctions do help structure this protean subject. The Noailles, for example, find themselves in the tank section — although surely an argument could also be made for putting them among the wet rooms, where they’d join a mythic but never realized pool, also designed in the late 1920s: Adolf Loos’s unsolicited goldfish bowl for Josephine Baker (1927), which formed the centerpiece of the Parisian house he planned for her. Another celebrated example from the era, Julia Morgan’s Neptune Pool at Hearst Castle in California (1924–36), finds itself among the vases, where it joins Arquitectonica’s PoMo Pink House in Miami (1973–78), and Laurinda Spear and Rem Koolhaas’s unbuilt house for the review Progressive Architecture (1975). Koolhaas appears twice more, first among the ponds, with OMA’s sylvan reflective tank at the Maison Lemoine in Bordeaux (2003), and then among the wet rooms, with the rooftop pool of Paris’s Villa dall’Ava (1984–91), suspended above glass but, in typical contrary Rem fashion, rather difficult to reach, since he didn’t want the poolside view of the Eiffel Tower to become the climax or raison d’être of the house. Perhaps even more willfully perverse was the unbuilt pool designed by Didier Fiúza Faustino for his friend Fabrice Hybert, in 2003, where the concrete beams of the house’s structure crisscross the water’s surface, making it impossible to swim in it (at the show’s opening Fiúza Faustino explained that he wanted it to be a relaxation and not a sports space, which makes its inclusion among the tanks a little odd). Meanwhile, back among the wet rooms is a house directly inspired by both the Villa dall’Ava and the Maison Lemoine: Ensamble Studio’s Casa Hemeroscopium in Madrid (2005–08), whose cantilevered concrete gutter of a pool has adorned many a Pinterest board.

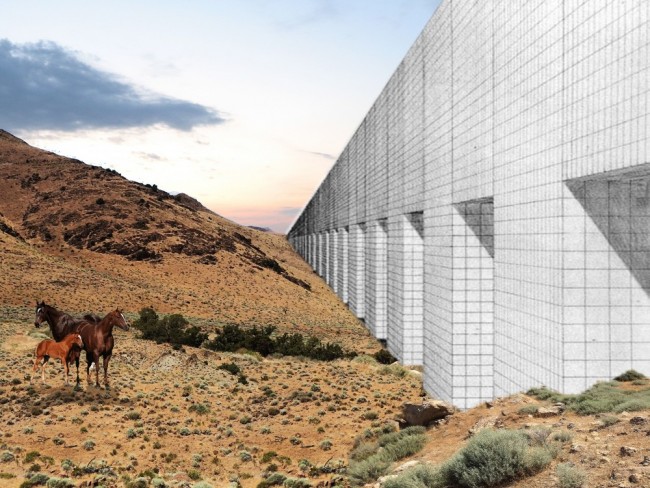

The Hand House, 2009, originally designed by Andreas Angelidakis for the PIN–UP Case Study House series.

But in addition to well-known favorites, the show includes some great examples of less publicized pools, such as Julien Montfort’s Maison-piscine I (Saint-Cyr-sur-Mer, 2001–03), where swimming becomes the principal domestic activity, Ricardo Bofill’s blood-red garden pool in Monstras, Spain (1973), or Richard England’s theatrically PoMo “A Garden for Miriam” at St. Julian’s in Malta (1982). There's also Andreas Angelidakis’s Hand House, one of several new Case Study Houses originally commissioned by PIN–UP for its Los Angeles special in 2010. As Angelidakis explained, the design “attempts to sum up a portrait of Los Angeles as a city of infrastructural crisis, impending disaster, and celebrity paranoia. The first gesture on the site is purely infrastructural: the site line is offset into a thick, double-layered concrete base that turns the lower part of the property into a water basin, a reservoir. On a thunderous February night, a mudslide is imagined and part of the basin fills with earth, forming an impromptu beach … The mudslide reservoir (thus forms) a large swimming pool, complete with its own sandy beach.” In this one building, Chinatown and Sunset Boulevard are deftly combined — two celebrated movie portraits of L.A. in which water and pools are key.

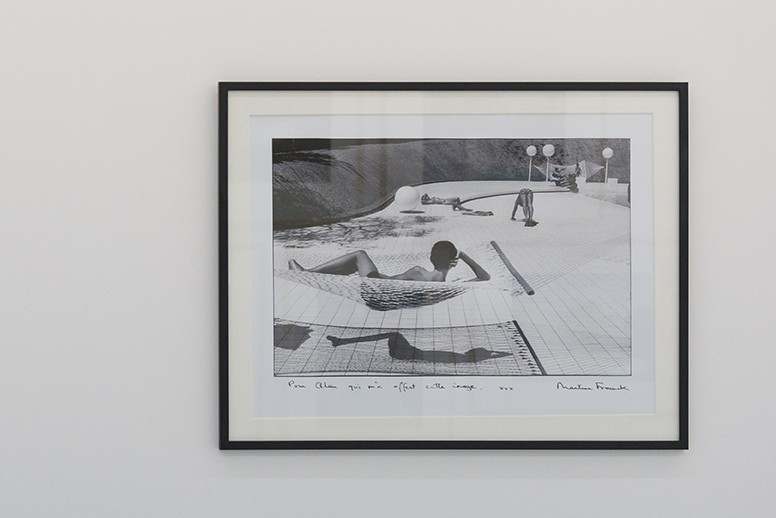

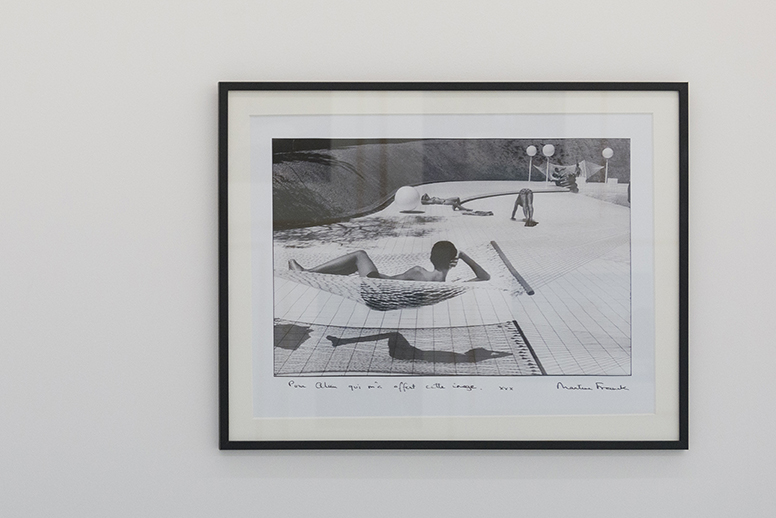

A photography by Martine Franck of a pool designed by Alain Capeilleres in Le Brusc, France, from 1976. CreditMartine Franck/Magnum Photos

Every year, to accompany its architecture show, the Villa Noailles highlights a remarkable local building in the surrouding Var region of France (a couple of seasons back it was Barry Dierks’s Villa La Reine Jeanne). And this year Lafore and Martinez Barat have uncovered a gem of a pool in Alain Capeillères’s extraordinary creation at Six-Fours-les-Plages (1972–75). The Marseille-born architect — to whose memory the pools show is dedicated, since he died shortly before it opened, at the age of 85 — married well, to the point where he no longer had to work for a living (which presumably explains the rarity of his built oeuvre, a great pity given the enormous promise he showed). And indeed the Six-Fours-les-Plages pool is a love letter to his wife, Lucie. Bothered by both the wind and the oil pollution in the real Mediterranean, Capeillères decided to dig out his own abstracted version of the mythical sea in his back yard, excavating 15 feet of earth to create “a Mediterranean space that’s even more acute than the south of France.” He filled it with acres of gridded white tiles, meticulously calibrated to minimize cutting, that are set off against dry brown earth on which not a single blade of green is allowed to grow, apart from parasol pines and cypresses that are silhouetted against the Grand Bleu itself. This sensuous, abstract, almost urban environment, dotted with lamp stands and palm trees, had its 15 minutes of fame thanks to a 1976 photo by Martine Franck and a 1978 movie, Le Maître nageur, directed by Jean-Louis Trintignant (check out our POOL PARTY again), but afterwards was forgotten. How wonderful to discover it again, a survivor from an age of radical optimism, when man still (just) believed his mastery of the environment could lead to endless hedonism for all. Ordre et beauté/luxe, calme et volupté…

Text by Andrew Ayers. Domestic Pools: l’architecture des piscines privées at the Villa Noailles, Hyères, France, through March 18, 2018. Click here for more information.

All images by Lothaire Hucki, courtesy Villa Noailles.