OMA’s Big Adventure In The Desert And How It Gloriously Failed

For some time now, the world’s most influential architect has been living in the middle of nowhere. Not physically: Rem Koolhaas — founder of OMA, Pritzker Prize winner, author of Delirious New York and S,M,L,XL — continues to be a resident of his native Netherlands, though he is no less at home in Moscow, London, or Doha, or in the spaces in between them, which he regularly inhabits in the course of his global peregrinations. Intellectually, however, Koolhaas has been dwelling in the wide-open places, the pastoral frontiers previously seen as beyond the pale of the built environment. Cities represent “the ancient parts of civilization,” the designer has lately claimed; the rural condition is “new,” an emerging posthuman landscape “occupied by machines.” This, Koolhaas contends, is where the action is, and this is where he wants to be.

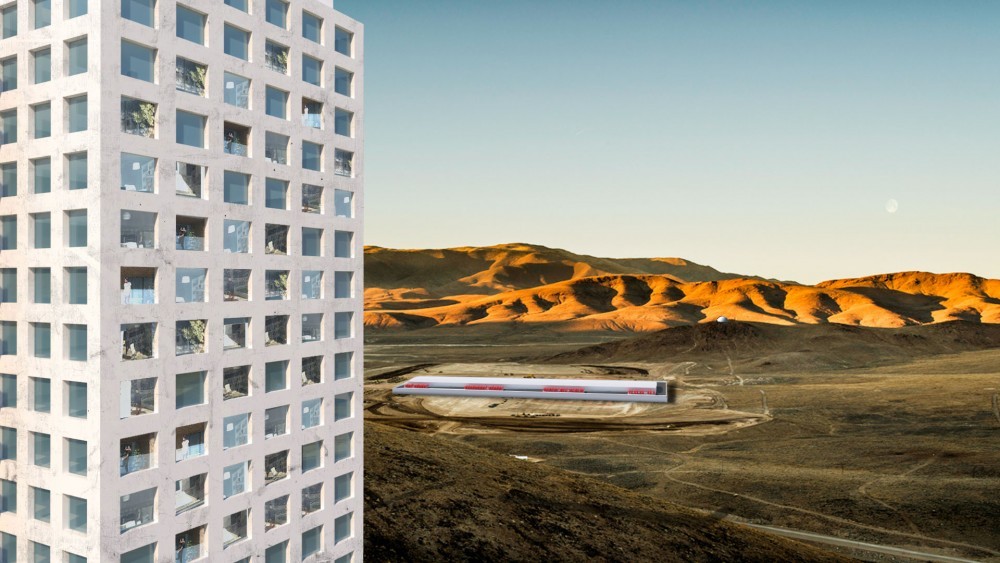

Essays about and lectures on the countryside have been staples of the Koolhaasian repertoire since at least 2012, a research project that will culminate in a high-profile exhibition, Countryside: Future of the World, co-curated by the architect and set to debut in February 2020 at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. Yet there’s already a non-urban Koolhaas scheme you almost certainly haven’t heard about, one that promised, at the outset, to be the most consequential product of his campestral phase. Somewhat out of the public eye, an OMA study was undertaken in America’s Great Basin Desert, a project that focused on many of the ecological, technological, and cultural insights propounded by the firm’s founding hetman with respect to the exurban sphere. Had it been built, the proposal would have left an indelible mark on the American West, transforming it, in a very real sense, into Koolhaas Country.

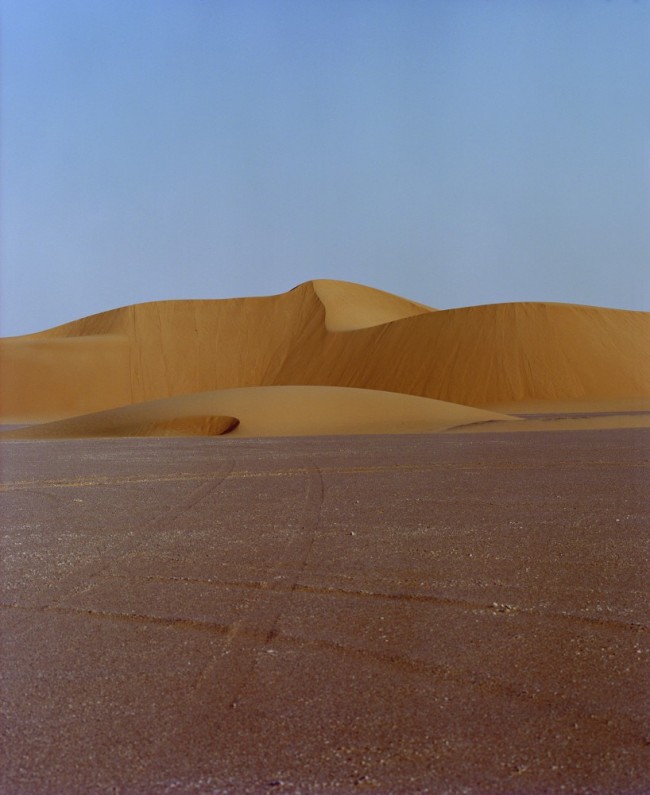

-

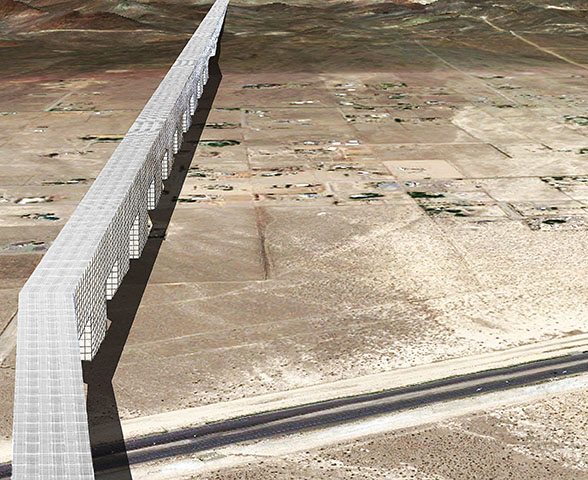

Fascinated by the proliferation of data storage centers, tech startups, and logistic companies in the American desert, OMA proposed mixing them with cultural elements such as Land Art, museums, and hotels.

-

This version embedded all amenities including the pool into an artificial crevice in the desert ground.

-

A "barren landscape where scale and function are transcended:" the American desert represents the perfect foil for OMA's desert habitat.

Would have — but didn’t. Despite their potential, the designs were not, and will not be, executed, chiefly as a result of their own ambition. The project’s failure is in a sense as telling as its realization might have been, an object lesson in the limits of certain varieties of conceptual practice when applied to rural areas as they actually exist. (Because of the specifics of how it failed, some of the details had to be redacted in this retelling.) The desert schemes that issued from OMA constitute some of the most compelling work and contain some of the most striking images to come from any architecture firm in a long while. By themselves, they’re enough to prompt a ruminative “what if,” as well to merit some exploration, in a mode Koolhaas himself has long favored: an archaeology of the present.

At the time, the CEO of a prominent cultural institution in an important North American desert city was seeking to expand the museum’s modest downtown home. The original notion had been fairly conventional: to find an adjacent site and use it for expanded gallery space, as well as for storage and scholarly access to the museum’s extensive archival holdings on monumental minimalist and Land Art — material on everything from Michael Heizer to Burning Man. “We have more than a million objects,” notes the CEO, and the museum was understandably eager to extend its proprietary claim on the artistry of the desert: if one imagines a giant isosceles triangle connecting Marfa in the south to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in the north, with Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field and James Turrell’s Roden Crater on its eastern and western flanks, the museum sits perfectly to the upper left, at the point closest to some of the great Californian cities of the coast and equidistant from the Mexican and Canadian borders.

-

One proposed version of the project took cues from Michael Heizer's Land Art sculpture Double Negative (1969–70).

-

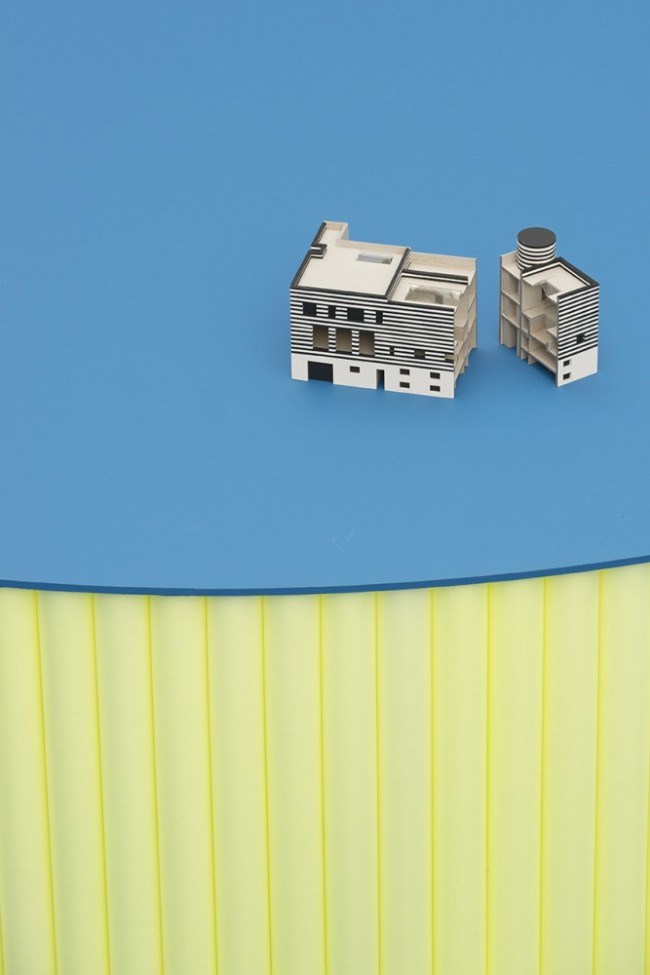

Viewing rooms and hotel rooms would make the most of the unusual proximity between art, landscape, and available technical and logistical facilities.

-

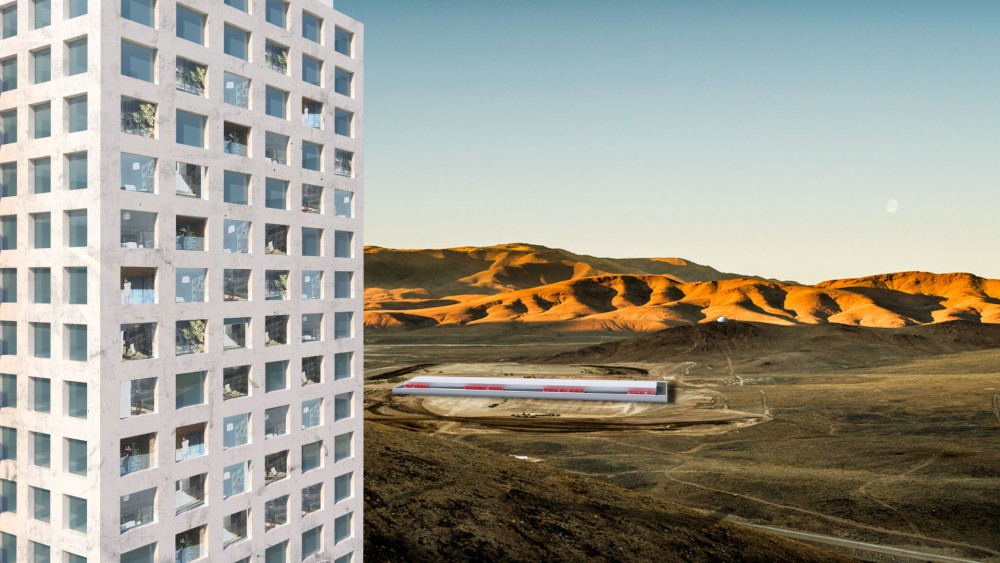

The proposal for Tower Art Hotel included private viewing rooms.

-

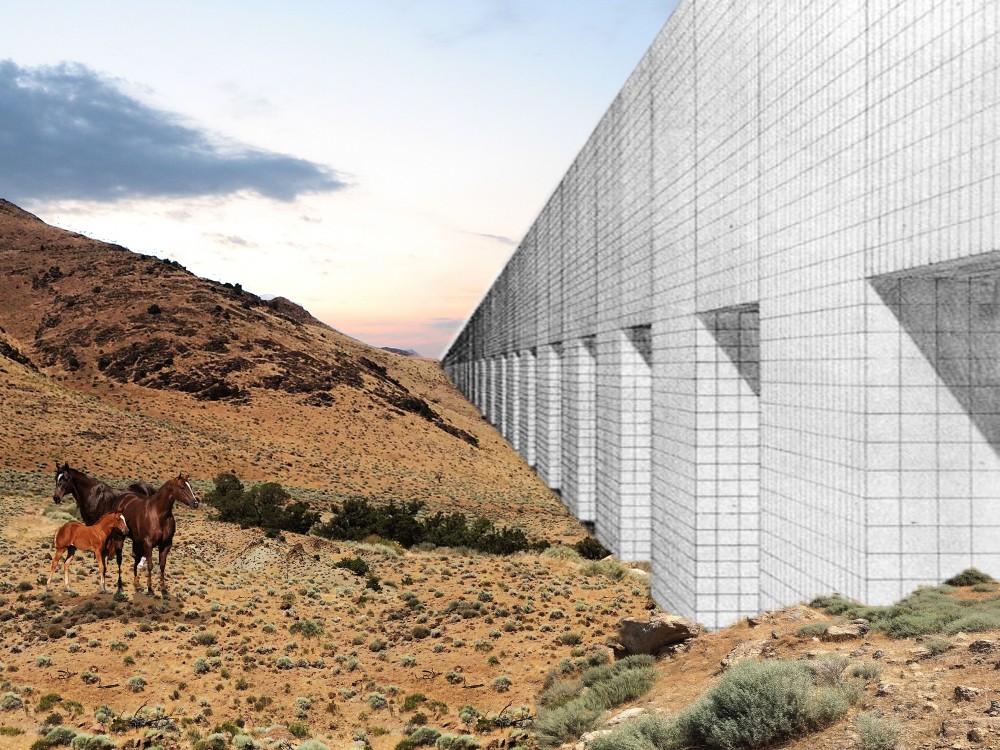

OMA was inspired by Superstudio's Continuous Movement (1969–70).

Koolhaas understood the area’s artistic background before he arrived there. What surprised him was everything else. On a subsequent trip, the architect was given a tour of a 107,000-acre sprawling development site, which we’ll refer to as the industrial center, about 20 miles east of downtown on Interstate 80, privately owned but operated in partnership with the surrounding county. Its proprietor, who began his career in the brothel business, escorted his visitor around the site, and what the architect saw astonished him: a Berkshire Hathaway-owned power plant, one of four, pumping out 1,100 megawatts; a full infrastructure of roads, railways, and fiber-optic cable; and, most importantly, buildings — constructed by tenants like Tesla, PetSmart, and Walmart — some 15 million square feet of steel sheds, inside of which was… nobody. “The human is actually the intruder,” observed Koolhaas, his fascination growing as he encountered structure after structure full of materiel, processors, sensors, HVAC systems, cameras, and few or no people. Interest turned to enthusiasm when Koolhaas encountered the so-called Citadel, the local headquarters of a data-storage specialist, billed by the company as a “technological fortress” — an ultra-secure, renewably powered facility for storing digital information. That was when the lightning bolt struck. “This is the future,” Koolhaas declared. “Let’s put the new museum here.”

Back in Rotterdam, the OMA team set to work. In a series of schemes, the designers imagined an art space that partook equally of the desert landscape and the technological landscape of the industrial center. More than just a museum, their proposal grew to encompass an array of functions including a new home for the museum’s research and education arm and a hotel, one that could host corporate visitors as well as art patrons, making the whole compound a genuine pilgrimage destination for cultural adventurers. Different conceptual solutions saw the new structures contained in a single loop lofted above the desert floor, or winding Paolo Soleri-style through the topography, possibly by way of an artificial ravine, or overlaid upon it in the manner of Superstudio’s Continuous Monument of the late 1960s. Inside, guests in the hotel could stay in rooms of uncanny elegance — shades of Richard Hamilton in their surreal domesticity — then drift down to the museum to gaze at masterworks with the desert and the hulking sheds as a backdrop, like a view of Mars complete with spaceships.

-

Inspired by the formal openness of the site, OMA submitted a variety of proposals, including one where amenities were grouped in a tower.

-

Proposal for a room in the Land Art-inspired Topography Art Hotel. In rooms that are carved directly into the rock, guests are encouraged to spend quality time with artworks while overlooking the canyon.

-

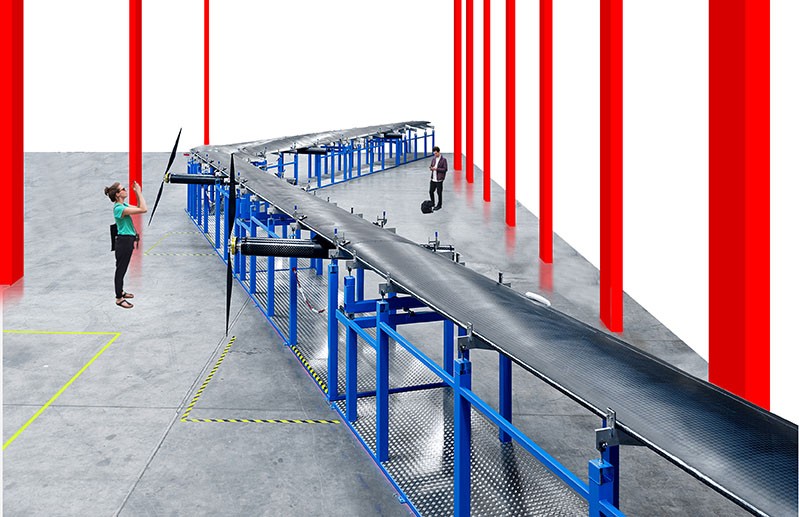

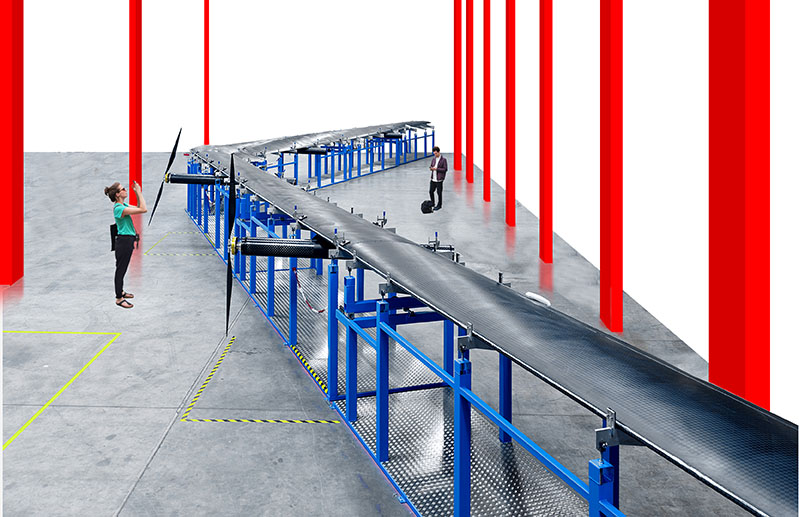

This track would make it possible for the artworks to be moved from the exhibition spaces to individual rooms.

-

In these spaces artworks, usually stored in black boxes and traded, finally become visible and accessible.

Unearthly as it all sounds, the museum was taken with the idea, as was the industrial center, which offered 20 acres to sweeten the deal. But OMA was not done dreaming. Jeremy Higginbotham, the firm’s director of business development who also hails from the area, was closely involved with the project from its inception, and, as he notes, there was a perfect coincidence in the mission of the institutional client and the techno-industrial environment: “Those data centers provide perfect art storage conditions, oddly enough: excellent security, and just the right temperature.” In its most daring proposal, OMA imagined “invading the centers,” says Higginbotham, with institutional arms stretching into the Citadel sheds to create hybrid spaces, half data and half art. The interior renderings imagine the storage facility’s sterile gridded catwalks peopled with curious art-lovers while the surveillance screens of the watching guards blink onto images of Warhols.

It was, perhaps, all too much. The museum and its partners began to recognize just how difficult it would be to execute even the most modest of OMA’s plans. “It was probably too remote to begin with,” says the museum’s director. There were problems with the site and with the hotel, and with all the different constituencies that always clamor to be heard in major projects such as this one. In the end, the logistical challenges were too great, the distances too far, the expenses too high, and the museum and the industrial center parted ways. The OMA desert episode was over.

-

There would be a hybridization of the data storage facilities with exhibition spaces and the museum's restoration and handling departments.

-

Visitors would get a holistic view of the institution's various operations.

-

In these spaces artworks, usually stored in black boxes and traded, finally become visible and accessible.

Or at least this part of it. Troy Therrien is the Guggenheim’s curator for architecture and digital initiatives, and Koolhaas’s collaborator on the upcoming countryside exhibition. As he points out, the discourse surrounding posthumanism has been plagued by “fear-mongering,” with many bien pensants fretting over “our future robotic overlords.” Therrien adds that “a new narrative for this architecture is wanting,” and into that empty discursive space a project like this institutional-industrial hybrid, even unbuilt, makes a valid point. It is, at the very least, an argument worth having.

What that argument portends for the discipline of architecture, and its place in the brave new countryside, is another matter. One of the primary (and literal) revelations of Koolhaas’s research into the non-urban is that much of what goes on there goes unseen, the artificial world stealthily pervading the organic one far from the glare of city-based media. What OMA sought to achieve in this exurban desert space was a spectacle of the techno-rural, one that would make apprehensible all the invisible processes and systems that are quickly remaking places like America’s western desert. But the reason we don’t know about what goes on at the data center is because we aren’t meant to: the paradox of a truly posthuman environment is that it is inoculated, by definition, from the kind of human intervention that OMA sought to perpetrate. Koolhaas’s conviction about the power of the new countryside wasn’t wrong; in a sense, it was only too right. In this round architecture lost, and the desert won.

Text by Ian Volner.

Images courtesy of OMA.